In the discussion on my initial criticism of the ACL over its handling of the rip’n’roll billboard fiasco a friend asked if I had any examples of positive alternatives, namely, Christian groups that engage in public debate without straying from the message of the gospel (a criticism I leveraged at the ACL).

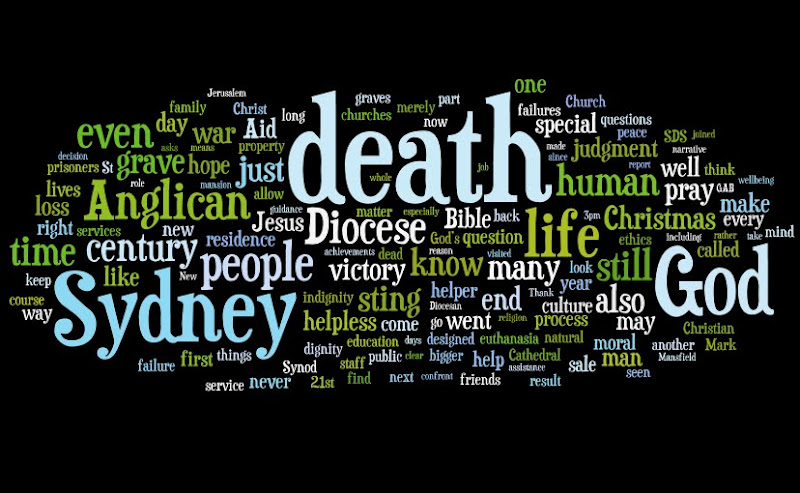

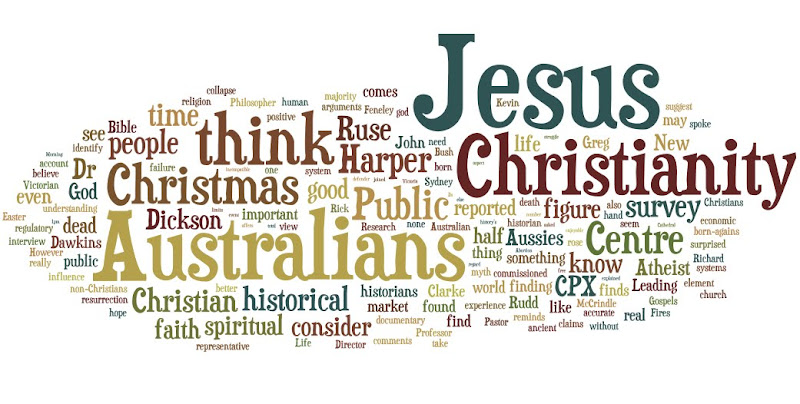

Now. I’m aware that Wordle isn’t the best measure of how “on message” an organisation is, but it certainly helps give a picture of what an organisation’s focus looks like.

The Sydney Anglicans were one example I put forward as an example. Here’s a wordle of their media releases.

The Centre for Public Christianity is another. They don’t necessarily comment directly on political issues (perhaps they should) but they do engage with the news cycle. Here’s a wordle of their releases.

Compare that with this ACL wordle from my post last week:

Now, some caveats. The ACL write more releases about more issues with a different purpose to these other two organisations. I recognise this. And my point remains that this proactive media strategy has left them as the default spokespeople for Christian belief in Australia. I’ve had some fruitful email conversations (from my perspective) with some ACL representatives since my last post. I won’t talk outcomes, but I think they’ve at the very least heard and acknowledged the point the post made. While I think the ACL get good coverage from their releases (releases get picked up in some form) the coverage is not usually favourable or positive. At some point as a PR person I’d be questioning the value of speaking if my position was never properly represented. In PR we value stories with an equivalent advertising spend and usually a multiplier based on how much the story represents our view. Unless the ACL subscribes to the “all publicity is good publicity” maxim, I’d say their multiplier is so low as to be non-existent, and their media coverage is hurting their cause. And worse. Hurting the gospel. My working hypothesis is that it is possible to speak on public issues without removing the gospel of Jesus from the picture. The questions are how, and what the PR “win” is. I’d say the Centre for Public Christianity has the best Christian PR approach in Australia, and the Sydney Anglicans aren’t far behind. Even when stories featuring Archbishop Peter Jensen are negative he usually manages to make sure the gospel is clearly articulated and linked to his response. That’s an art.

A Case Study in Gay Marriage

The Archbishop has recently featured in the SMH for an opinion piece he wrote elsewhere on the gay marriage issue. Here’s another confronting moral issue of our time where there’s every chance the gospel is going to be lost in a sea of moralising reinterpreted as bigotry (or homophobia). Sadly in this case, and I suspect because it was the result of a slightly underhanded move where quotes were lifted from an article for a Christian audience (Southern Cross Newspaper) and placed in a story for a different outlet (The SMH) so the angle was doubtless well and truly form before any follow up interview took place and thus the initiative was lost.

Now. I recognise that an article in the church’s own newspaper is the perfect place to discuss issues from a Christian perspective, it’s for the church, not for the public at large. So I’m not really interested in judging the approach to the issue they’ve taken there (which I agree with), nor in whether or not they should have expected the media to pick up the story and run with it.

I’m wondering if part of the issue with the way we approach debates regarding homosexuality is that we lack empathy with those who identify as homosexual or struggle with same sex attraction. We are able to put ourselves in the shoes of heterosexual moral offenders with a “there but for the grace of God go I” mentality. But most of us have no idea what its like to grapple with an outside the norm sexual orientation. And I think it shows. And I think our approach to the issue of gay marriage might be a little bit more nuanced if we firstly realised that our opposition to gay marriage is largely driven by our Biblical convictions, not necessarily our natural ones, and secondly realised that the origin of these convictions means we should think carefully about how we approach legislation in a democracy which definitionally seeks to serve all constituants not just the powerful majority or noisiest lobby group.

I’ve had a couple of stabs at articulating a position and approach to gay marriage previously (and also posted about the danger of slippery slope arguments like the one the archbishop employed over at Venn Theology), and I think these would play out a little better in the press.

Gay marriage makes an interesting PR case study, particularly in the light of this article dealing with the Sydney Anglican position on the issue.

Arguing against gay marriage is going to end up confusing the gospel message in the public eye. Which is really my major reason for not fighting the issue. We end up becoming just like the ACL, no matter how nuanced our position. For two reasons:

a) because the media is hostile to us, and

b) because people like the ACL keep making this about “Christian worldview inspired family values”…

Stories like the one on the Archbishop’s position are normative mainstream media treatments of Christian statements about moral issues. I’d be interested to see the story if we framed our approach around questions of identity, and being able to identify, in our society, by whatever belief, creed, or sexuality we choose. I think that’s a message with traction that would possible allow Christian ministers to continue to define marriage traditionally, present the gospel clearly as we articulate our position on homosexuality (“we believe we are not defined by our sexuality but defined by following Jesus which has flow on effects for how we see sexuality”)… every time we speak out on a position morally the story is going to end with a quote like this one:

‘The archbishop would acknowledge we live in a multi-faith society, and as such he must respect that his views should not be imposed on those religions that want to perform same-sex marriages, such as the Quakers and progressive synagogues, or the civil celebrants who perform 67 per cent of all marriages,” he said.”

Here’s how the ACL tackles the issue in a Media Release. Here’s a thought. Rather than angrily responding to a minority who face a fair bit of ostracism for having outside the norm sexual orientation for using the words “bigot” and “homophobe” what if we turn the other cheek. And empathise with them. And lovingly disagree.

“We are also yet to have a debate in this country free of abusive slurs such as ‘homophobe’ and ‘bigot’ and until that can occur, not one should jump to conclusions about the inevitability of redefining marriage.”

It doesn’t really matter what we say in this debate. The other side is always going to reinterpret our position as an attack on their core identity (why is sexuality an anchor point for identity anyway?). So why not just stick to presenting the gospel in a gracious and winsome manner, where we do more than pay lip service to gay rights (which every Christian statement seems to be based on). Why not talk about how Jesus loves all sinners – gay and straight. And how he calls us to find our identity not in our sexuality, but in submitting to his Lordship? The media will still be hostile to us. But at least we’re not confusing the moral issue with the gospel message, as though homosexuality is worse than other sins.

The question then is essentially what would Jesus say about gay marriage, to the state. Because that, trite as it sounds, should frame the approach we take to the state. While Jesus clearly taught that marriage is a relationship between one man and one woman (Matthew 19:4-6) he wasn’t really a political revolutionary speaking out against the immorality of the Roman empire. And there was plenty to criticise.

Image Credit: Che Jesus has its own Wikipedia Entry

I’m not sure what sort of normative ethical principles of engaging with the state can be drawn from Jesus’ “render unto Caesar” approach to paying taxes. Or from his lack of protesting about the empire’s immorality (when his disciples clearly expected a political revolution). But I’d suggest his approach with sinners – lovingly calling them to repent, because God’s kingdom was near, should probably have some bearing on how we approach issues of morality. The problem is that this can potentially lead to political quietism, where we say nothing about the way our government runs. Which would be a bizarre position to adopt. Especially in a democracy. And especially when we have a responsibility to seek the welfare of our city (some previous posts on that note: 1 and 2). So, and I’m happy to flesh this out in the comments, I think there’s a place for speaking out politically in a WWJD approach, but I think it should be motivated by a desire to love the lost and proclaim the Lordship of Jesus. Not impose that Lordship by proxy. It would be interesting to examine how the Christian church changed the Roman Empire, in terms of their views of Christianity, but that would be a pretty long post.

What would Paul Do

Another interesting paradigm for understanding a Christian relationship to the state comes from Paul’s trial before Agrippa in Acts 26. Now. Paul was defending himself against criminal charges, but he was also essentially lobbying for Christianity’s legal status before a hostile state. We’re increasingly in a position where parallels can easily be drawn between the state we live in and the idyllic, though very immoral, Roman empire. Paul meets this king, and in his defence, he preaches the gospel of Jesus and essentially appears to be evangelising Agrippa in the process.

“28 Then Agrippa said to Paul, “Do you think that in such a short time you can persuade me to be a Christian?”

29 Paul replied, “Short time or long—I pray to God that not only you but all who are listening to me today may become what I am, except for these chains.”

There’s a Biblical model for lobbying. Right there. I won’t revisit old ground too much, and this is already an excessively long post. But in my next installment I’ll have a go at writing a media release that demonstrates how I think one might stay “on message” in this debate.

Comments

I like what you have to say about reframing the debate on issues of identity and love for all sinners.

But I really don’t like your suggested quote: “his views should not be imposed on those religions that want to perform same-sex marriages.” This is precisely the frame those advocating same sex marriage want.

Is this:

a. cleverly subverting the debate in order to get clear air to speak about Jesus? OR

b. conceeding that whatever Jesus says is irrelevent unless you belong to a church

I think (b.) & I think wherever it has been tried it has failed.

(In any case it would be a substantial change (& not just a change in style) from what the Archbishop is saying.)

Hi Michael,

Thanks. I think what I’m after is the ability for us to continue to articulate that Jesus says that marriage is between a man and a woman. But that in a secular democracy we recognise there are limitations as to how far we can apply Jesus’ teachings and they make a whole lot more sense if we submit to Jesus’ lordship.

I just keep coming to the fact that we take our position on a faith that others don’t share, and that if there is any doubt at all about the truth of Christianity then it is pretty wrong to be using our views as the basis for the entire society. While I don’t doubt that Christianity is true there are plenty of Australians who believe it is definitively not true. So I think we need to factor that in to our approach to politics. It’s also a lot more gracious. In the OT the knowledge of God is the basis on which the law is followed (the law comes when Israel is pretty sure that God is God) – shouldn’t that frame our approach? We’re trying to protect our Christian definition in the face of people who increasingly know nothing of the framework it comes from. Which is part of the problem where the message of a saving relationship for sinners, by grace, through Jesus gets lost in a sea of moralism.

So I’d say it’s a and b, but with a slightly more nuanced position – whatever Jesus says only makes sense if you belong to his church. It’s not that it’s irrelevant. It’s that we need to make the case for its relevancy where in the past that might have been assumed. And the current voices in the debate aren’t doing that.

Hey, Nathan – I have similar ideas about approaching ethics from the perspective of personal identity. I don’t have the answers, but I am on the public record being torn asunder by a parliamentary committee on same-sex parenting whilst trying to frame my argument in those terms.

I made a hash of it, but if you want to see how it played out, I have a copy of the Hansard report. If you email me I’ll send it to you (I couldn’t find it online – you might be able to: Monday 4th April, SA Legislative Coucil, Social Development Committee.)

Have you seen Jonathan Chaplin’s essay ‘Talking God: the legitimacy of religious public reasoning’ http://www.theosthinktank.co.uk

Britain aint Australia but he helpfully writes about faith based arguments in liberal democracies