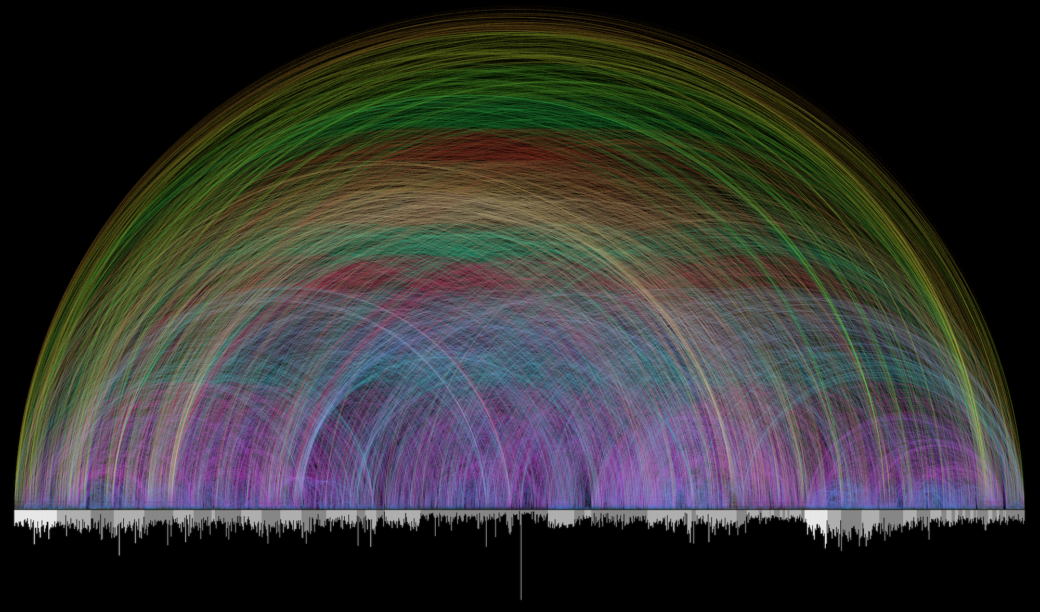

Have you ever seen this image?

It’s a stunning representation of the cross-references in the Bible from a guy named Chris Harrison. There’s a similar visual aiming to highlight contradictions in the Bible (most of those don’t stand up to much scrutiny). It’s not new, I first posted about it back in 2010, but it serves as an illustration of my point here.

I’ve been thinking a bit about preaching — and just to be clear, I’m not wanting to position myself as a master of the craft here. Not at all. But I have a growing set of pebbles in my shoe regarding the way we tend to see the task of preaching within churches who claim we’re shaped by the Bible. These pebbles include the assumptions we bring to the task of interpreting the text (exegesis), to the speech-act of transmitting the text, and to how we see it as a living and active word within the life of a church community shaped both by the text, and by the God who speaks through it, while shaping us as receivers of his word by his Spirit. I’ve written about my issues with the sacred cow of expository preaching — especially when it is reduced to transmitting content (locution) rather than speaking in a way that aims for the text’s persuasive intent (perlocution).

As I ponder the task of preaching, and its place in the life of the plausibility structure — the community — that is the church, I see a huge part of the task of the preacher in the modern church as giving people back their Bibles, in the hope that our communities will become what Stanley Hauerwas described as a “community of interpretation” or a “community of character” — one that puts flesh on the bones of the story of the Bible as it rehearses and performs it together in the world.

Why giving people back their Bibles? Well, because I reckon the modern Protestant church, for all its original protestations against the Catholic Latin Mass has been systematically removing the Bible from the hands of its people — both reducing it from narrative (and ancient literature) into a series of propositions and axioms that fit a modern grid, and by using it as a weapon to justify a range of abusive behaviours; from domestic violence, to abuse, to cover ups, to racism, to the mistreatment of people whose experiences see them operate as sexual minorities — the Bible has been used to prop up worldly power structures, even literally, as a prop weapon wielded by Donald Trump on the steps of a church after his militarised security personnel tear gassed a bunch of divine image bearers.

So often the word of God hasn’t been used as a sword to cut us — including, and perhaps especially, the powerful — to the heart and cause us to repent by turning to God and finding life in his kingdom, but as a weapon wielded by powerful people with sinister agendas. Recent decisions by ‘courts of the church’ in conservative denominations in the United States — and no doubt, upcoming decisions in our own denominational settings — have effectively undermined the Bible’s goodness, and its function as God’s living and active word. And the progressive arm of the church has not helped here, in its attempts to deconstruct the power of these oppressors it has often deconstructed the power of the Bible itself, through critical scholarship that secularises the process and content of the Bible, or fragments the unity we see in the visual above, and through various models of interpretation that don’t simply prioritise the perspectives of marginalised communities in the modern world, but risk colonising the text through the eyes of just a different ‘enlightened, capitalist, liberal’ western viewer.

And whatever side of the conservative/progressive spectrum one comes from — there’s an overwhelming cacophony of information out there seeking to debunk, prove, or educate the reader — it’s not uncommon for me to have a member of my congregation fact checking my sermons on wikipedia, or via a sneaky google, in real time.

This stuff isn’t just ‘out there’ — the debates aren’t just happening in the abstracted ivory towers of the academia, or on Twitter. These descriptions of the modern world aren’t just things I’ve read about, but realities I have to grapple with every time I open the Bible to teach from it. Maybe this speaks more to my context, but I’m preaching every week to people who had overbearing or abusive fathers, who’ve experienced family violence justified by Biblical texts, who’ve been in spiritually abusive contexts or constructs and are trying to recover, rather than deconstruct, women who’ve been subject to various forms of purity culture or the patriarchal sense that they are lesser, or that faithfulness looks like “mothercraft,” and sexual minorities who’re trying to pursue faithful obedience to God in church settings where God’s word has been used to justify their parents cutting them off from their family, to attack their choice of language to describe their experience and attempts to faithfully steward their hearts, minds, and bodies in obedience to Jesus, and their choice of cake colour.

The Bible has been used as a weapon, and this has often been a function of people not grasping the richness, complexity, and unity of the Bible’s story. It’s often done through ‘clobber passages’ or proof texting in ways that produce trauma, and a variety of trauma responses when someone with institutional authority says ‘the Bible says’…

I don’t know if other preachers are grappling with this dynamic, or if it’s just that I’m woke or whatever. But trauma is real; and if you haven’t had someone shaking or crying in the middle of a talk, or even walking out, because of something triggered by a particular verse or phrase, then maybe it’s because your church community already bears the hallmarks of a place that isn’t safe for people with the experiences I describe here. When I’m preaching — aiming to ‘give people back their Bibles’ — I’d love to see these folks recover a love for the Bible not as a weapon used to destroy them, but to cut away the things that are destroying them so they might find life in the presence and love of God as his children. I’d love to equip them to fight back against the weaponisation of the Bible by knowing how the Bible actually works.

I also see my task as giving people their hyper linked Bible. The Bible on display in this infographic. I’ve been thinking a lot about what it looks like to preach the Bible in an age of hyperlinks — and where most people are going to interact with the Bible digitally rather than in paper and ink form. I’m not one for suggesting that technology change is something we should uncritically embrace as Christians — in fact, quite the reverse. And I’m totally down with the idea that digital devices (like writing before them, thanks Plato) have damaged our ability to internalise information. We process information in a pretty weird and distracted way, thanks to the hyperlink (and tabbed browsing), and yet, the beauty of something like Wikipedia is that it demonstrates how conceptually linked and integrative information is — hyperlinks can create hyper-distraction, sure, but can also help us push into intricacies and perhaps even reveal the artistry of God; the author of life, and the divine author of both the story that climaxes in Jesus’ death, resurrection, ascension, and the pouring out of the Holy Spirit in history, and the description of that story in the 66 books that make up our Bibles.

I’ve also been motivated by my friend Arthur once inviting me to imagine a generation of Christians brought up on the Bible Project, and just how wonderful the resources our hyper-linked communities have to be digging into the Bible outside the context of the Sunday sermon — the question ‘if stuff that good is out there, and wildly (and widely) accessible, how can I link my community to it’ is part of the thinking here for me. How do I turn the hyper-linked ‘fact checking’ from a bug into a feature and augment the teaching of the Bible that way?

This means, in my preaching, I’ve moved away from a few sacred cows, and I’m exploring what it looks like to preach to a generation of people I hope will be treating the Bible as a rich hyperlinked text — cause it is — worthy of deep meditation and that it also is compelling and beautiful and divine and human because of the unity of the story it tells, that lands us

Firstly, expository preaching tied to one passage. At some point in my training as a preacher I was actively discouraged from hopping around the Bible (and, I agree one can perform all sorts of textual gymnastics and tangents if one doesn’t do this carefully), and yet, whatever the passage you open the pages of your Bible to, or more likely, you flick to on an app, the passage has a literary context — it sits within an illocution within an argument, within a book (or letter), within a corpus, within a Testament, within a library (the Bible), within a narrative. I don’t think we can reduce our sense of the ‘locution’ — the message of a particular text — to the sentence, or words, before us — because the Bible is hyperlinked, and the whole context frames our understanding of the concepts the words used evoke, and the narrative that frames it. The obvious way to do this is to not simply go to the New Testament, from the Old, to show how Jesus is the fulfilment of the Old Testament, but to the Old Testament, from the New, to show the same. There are often direct quotes of the Old, in the New, that make this straightforward — the trick is to find not just quotes but allusions; imagery and evocative themes — geography even (ask my church family about my current obsession with mountains). In the past 12 months we’ve covered the narrative of the Bible from the starting point of Revelation — from creation (there’s lots of Edenic imagery in there), to fall (there’s lots of Babylon imagery in there), to the prophets (there’s plenty of Daniel and Ezekiel), to the victory of Jesus over sin, and death, and Satan, to the New Creation — and from the starting point of Genesis 1-12, tracing similar threads. I’m not sure I could conceive of preaching either Genesis 1-12 or Revelation without following the threads that are woven together in these texts.

Secondly, preaching small passages. Picking a manageably small discreet unit of text is one of the necessary implications of verse-by-verse exposition, or even ‘big idea’ preaching where a preacher has to demonstrate how a big idea is faithfully derived from the text. I’m not saying I’ll never do this again — different genres and books lend themselves to this sort of preaching (like in an epistle). I’m struck by how much intertextuality becomes more obvious if you give it a little more rope — so, for example, we worked through Matthew’s Gospel in the first quarter of this year and it was only by preaching on a three chapter chunk that I noticed how the parable of the sower, that ends with a listener to the word producing an abundant harvest of grain was in a sequence of parables about wheat, wheat, bread, bread, and fish — and then a narrative about Jesus — the model of the good soil — producing abundant wheat (and fish) in the feeding of the 5,000.

Thirdly, connecting a passage to the ‘design patterns’ it resonates with from the big story. I love the work the Bible Project does on how the Bible is a ‘unified story that leads to Jesus’ — but this has absolutely been my bread and butter my whole life; it was the milk I was nourished on by my parents, and the churches I have been part of since infancy. We can assume this context as preachers, and just preach the text in front of us, or we can open our communities up to the rich intricacies of the Biblical text in ways that make proof texting without this context much more difficult — and arguably make our understanding of the actual text we might build a community around richer and less distorted by reductionism. It’s definitely harder work, but, at least so far as I can tell, humanly speaking, it has been a comforting experience for those processing various Bible-related trauma.

Fourthly, prescriptive application. This is a step I’ve taken for a couple of reasons — it is not because I don’t know how I think people should live (it is, in part, because I don’t know that I’m an infallible enough guide to avoid lumping people with my own prescriptive hobby horses). The abuse of the Bible by people in authority, wielding the text as a sword, shows how fraught prescription is — and how it leads to the abuse of the flock preachers are tasked to feed. Application in sermons often takes the form of reducing description — whether in a narrative (for eg David and Bathsheba), or in the Bible’s narrative (for eg the Old Testament laws about bacon) — to principled prescription, whether general or specific. I’m struck by how often our applications are prescriptions for individuals as well, rather than about what a community that plausibly lives this narrative might look like, but that’s for another post. There are times when the Bible itself offers prescriptions — and in those times, where the prescriptions (the imperative) is grounded in the narrative (the indicative), I’m reasonably confident offering a prescription, but I’m struck also by how often those apparent ‘prescriptions’ are descriptive — like when we’re called to love one another, and then pointed to the example of Jesus, but not given an exhaustive set of specific behaviours. Even then I find myself moving towards description, or not being specific at all but letting the story itself, and the space we make around it as a community to have it sink into our bones and imaginations might actually be what produces the changed lives. I’m also hesitant because in a diverse church community I wonder if descriptive application, or simply the telling of the story or unpacking the meaning of the text and inviting people to find life not just in the narrative in one passage, but in the metanarrative that narrative belongs in.

We are people shaped by stories — whether a trauma story, a family system story, the stories we try to author for our own lives, or the ones told to us by culture — and we have a pretty good hyperlinked story to immerse ourselves in as individuals, and as a ‘community of character’ where we are being formed as participants in the story, and the body of Christ.

If you’re interested in what any of this looks like as I play with this idea — and sometimes it works better than others — you can find my preaching in podcast form here, I reckon this particular sermon is a decent example of the principles. I’m sure I could preach better. I’m sure. In terms of oratory, I have preached better (and sometimes shorter) in the past, when I was giving TED talk styled sermons with lots of illustrations, and cultural commentary, and without notes. I’m not claiming to be the finished product, but articulating a shift I’m trying to make both built out of a conviction about the nature of the Bible itself, and the task of caring for the people I’ve been tasked to care for.

I’m aware, too, that there are other ‘speaking roles’ in the life of the church that aren’t simply preaching/teaching — that encouragement, prophecy, exhortation, rebuke — are all types of speech that are grounded, too, in the Scriptures and part of using it. I’m sure the public speaking bits of a Sunday service can, and should, include those types of speech — just as I’m also sure that some of these types of speech need to be grounded in people having been given a hyper-linked Bible and the wonder at the one who inspired it first, and can happen in the context of safe and secure relationships — within a community, with the person doing the speaking, and with God. I’ve had much more profound and fruitful pastoral conversations with people dealing with the sorts of traumas I’ve described above, where the Bible has been open on the table, as a result of this framework than I might have had if I’d simply yelled clobber passages at them from the pulpit (or even just carefully expounded a series of propositions from one particular passage).

The one sacred cow I’ve picked up as part of this process — and, in part because the circumstances of our church community have changed such that we’re sharing a space, and a gathering, with people from a Church of Christ — is weekly communion and the tying of the ministry of the word to the ministry of the sacraments (or, as should be the case ‘the ministry of the word and sacrament’) — where communion itself is an invitation to participate in the application of the text, and the community shaped by the text, and where, a couple of times, joining together in making promises around a baptism has been the application too. Each sermon essentially culminates in an invitation to see ourselves as partakers in the story through our union with Jesus brought about through his death, resurrection, and pouring out of the Holy Spirit to unite us with him and each other. It’s not a silver bullet, but it has been a good discipline for me to make sure my sermons from a hyper-linked Bible are linked to the Gospel, and to our practice of remembering and proclaiming the Gospel to one another as we gather.

Comments

Thanks Nathan,

That’s really helpful. I sometimes find myself anticipating, as the preacher works through a text, “Oh he’s going to cross reference such-and-such now…” or “he’s going to bring out the nuance of that word or phrase in its richness,” only to be disappointed. When it does happen, it’s always such an ah-ha moment for listeners, and it really does reinforce the depth and breadth of the wonder that is our written word of God.