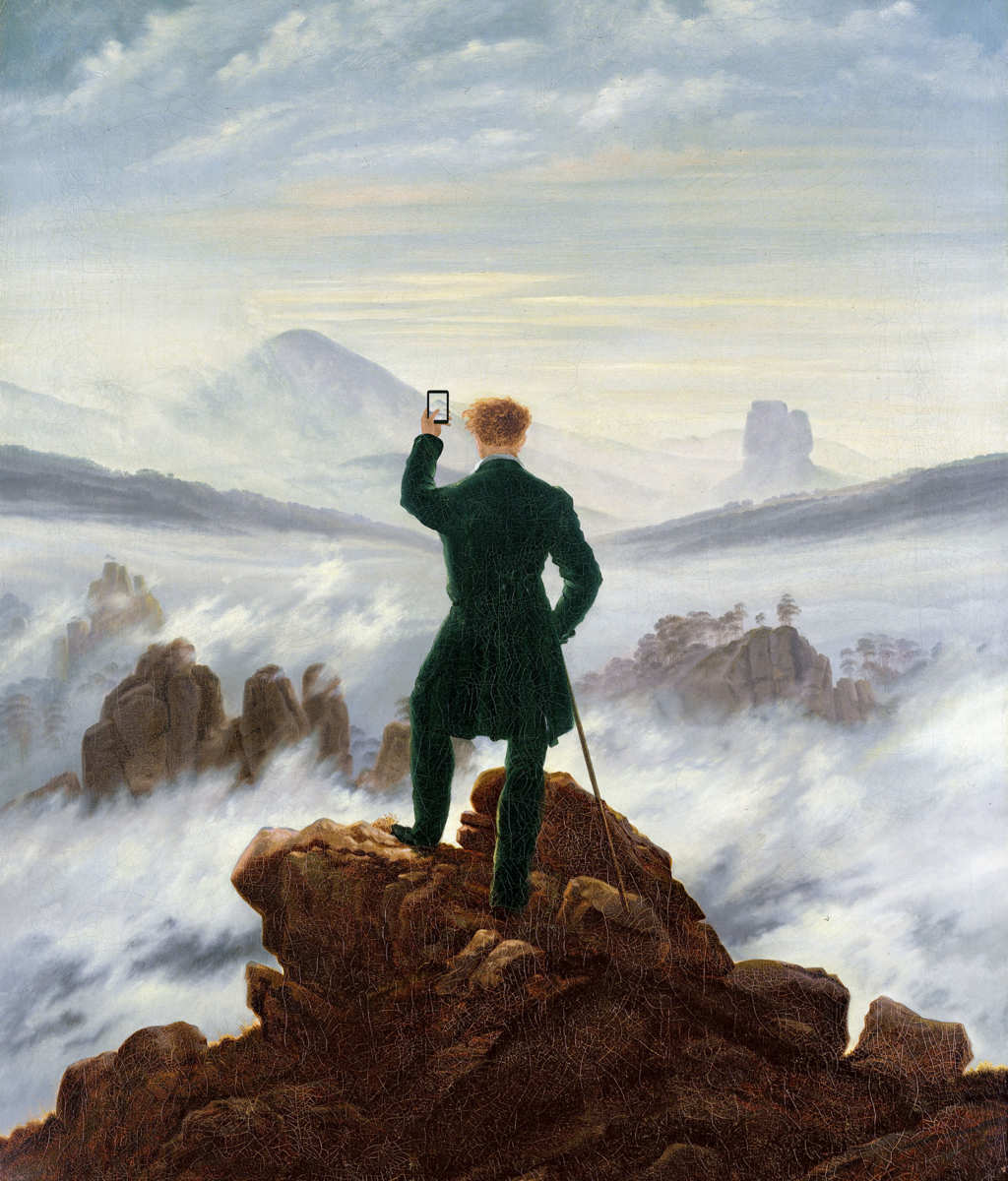

Illustration by Kim Dong-kyu Based on: Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, by Caspar David Friedrich (1818). From: Technology Nearly Killed Me, Andrew Sullivan, New York Mag, Sep 2016

“Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic” — Arthur C. Clarke

There’s a new Telstra ad that I love because it is beautiful, but that I feel overpromises on what technology can (and does) deliver; in fact, I think it misleads, and invites us to put our hope in the wrong places. But it is a beautiful ad that taps into some deep human desires.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6zGytq7ckS8

“See? We live in a magical world. We never have to wake up from our dreams. Our restless minds now free to wonder at the wonder of technology; at the magic we’ve created. Possibilities are like stars now infinite constellations fuelled by pure imagination; leading to one destination – to you, to thrive.” — Telstra

The world doesn’t feel as magical as it used to. That’s part of the central thesis of award winning philosopher Charles Taylor’s A Secular Age. Telstra’s marketing gurus seem to have tapped into the haunting sense of loss we have because of the evacuation of magic, or something ‘transcendent’ from our view of the world by suggesting technology itself is the way back; like somehow the answer to our longing for something more than the material is more material, just cleverer, just with the illusion of magic (because part of the evacuation of magic from the world is the belief that anything that looks magical is actually an illusion, which is why we call magicians illusionists now).

It used to be that life was magical; that every thing had some sort of spiritual significance, whether there were gods everywhere behind every event, like a poor harvest or a pregnancy, or in monotheistic cultures everything existed in some way within the life and will of the infinite God; Christians in particular believe that the material world, what Taylor calls the ‘immanent’ world, is somehow given life and significance (or more ultimate meaning) by its connection to the creator, and by Jesus, the creator’s creating and sustaining ‘word’ (transcendent) made flesh (immanent). Colossians 1 has a good example of this view of the world:

“For in [Jesus] all things were created: things in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or powers or rulers or authorities; all things have been created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together.” — Colossians 1:16-17

C.S Lewis didn’t just write fairy tales for kids and a bunch of Christian reflections on life; he also published academic work on literature, including a book called The Discarded Image which looked at how older generations viewed the world this way; as enchanted, and how that fuelled their creativity, their art, their literature, and so better answered the longings of the human heart for some sort of enchantment, he argued (in 1964) that we’ve lost something as moderns who have kicked the sense of the transcendent out of our world and settled just for the stuff we can see and taste and touch as ‘reality’ and our source of meaning; C.S Lewis would be a little suspicious of Telstra’s advertising I suspect. Even the best technology — the most luxurious things we can fill our house with — he said were a certain sort of ugly, precisely because of this lack of symbolism, or significance, pointing to anything beyond itself (and so we have modern, and post-modern, art, often wallowing in this milieu, and so soulless and empty).

“Luxury and material splendour in the modern world need be connected with nothing but money and are also, more often than not, very ugly. But what a medieval man saw in royal or feudal courts and imagined as being outstripped in ‘ faerie’ and far outstripped in Heaven, was not so. The architecture, arms, crowns, clothes, horses, and music were nearly all beautiful. They were all symbolical or significant-of sanctity, authority, valour, noble lineage or, at the very worst, of power. They were associated, as modern luxury is not, with graciousness and courtesy. They could therefore be ingenuously admired without degradation for the admirer.” — C.S Lewis, The Discarded Image

James K.A. Smith wrote an accessible commentary on Taylor’s massive tome called How (Not) To Be Secular, here are two key ideas from his work:

“It is a mainstay of secularization theory that modernity “disenchants” the world — evacuates it of spirits and various ghosts in the machine. Diseases are not demonic, mental illness is no longer possession, the body is no longer ensouled. Generally disenchantment is taken to simply be a matter of naturalization: the magical “spiritual” world is dissolved and we are left with the machinations of matter…There is a kind of blurring of boundaries so that it is not only personal agents that have causal power. Things can do stuff.”

“Taylor names and identifies what some of our best novelists, poets, and artists attest to: that our age is haunted. On the one hand, we live under a brass heaven, ensconced in immanence. We live in the twilight of both gods and idols. But their ghosts have refused to depart, and every once in a while we might be surprised to find ourselves tempted by belief, by intimations of transcendence. Even what Taylor calls the “immanent frame” is haunted.” — James K.A Smith, How (Not) to be Secular

The implications of these quotes are interesting when read against Telstra’s ad; a campaign designed to reconnect us with the magic we long for, via machines.

The first is interesting because it explains why we look to technology — machines — to enchant our lives; if matter is all that matters, if everything (the universe) is basically one big machine of cause and effect, filled with little machines (us), who make machines (technology) then we’re now likely to rely on technology to give us any sense of what we’ve lost because they’re the closest we get to matter with a soul; other than us, and we get to program the soul into them so they serve us. The second point explains why we want them to serve us by delivering the experience of ‘magic’; because that’s precisely what we’ve lost, and what we long for, and what we’re haunted by. We want matter to matter more than it does; we want a transcendent reality that stretches beyond us; this might be, as the writer of Ecclesiastes puts it, because God has set eternity on the hearts of humanity, but it might just be that we wish magic was real.

If Taylor is right then I don’t think machines; perhaps especially smartphones and screens; will deliver the answer our haunted selves are looking for, they might actually make the haunting worse; especially if all the science looking at what technology use does to our brains and relationships is true; and on this you should definitely read the Andrew Sullivan piece, Technology Almost Killed Me where that picture at the top of this post comes from; Sullivan is one of the world’s most famous bloggers, he went a year without tech, precisely because he felt he was losing himself into a totally ‘immanent’ way of life, and he wanted some transcendence; he found that silence, not distracting technological bombardment, was where something ‘magical’ could truly be found… he looks at how our western world has progressively killed the silence which used to enchant us, and in doing so have ensure our haunted longings for something more, for the infinite reality that silence throws us towards, are not truly satiated.

“The smartphone revolution of the past decade can be seen in some ways simply as the final twist of this ratchet, in which those few remaining redoubts of quiet — the tiny cracks of inactivity in our lives — are being methodically filled with more stimulus and noise.

And yet our need for quiet has never fully gone away, because our practical achievements, however spectacular, never quite fulfill us. They are always giving way to new wants and needs, always requiring updating or repairing, always falling short. The mania of our online lives reveals this: We keep swiping and swiping because we are never fully satisfied. The late British philosopher Michael Oakeshott starkly called this truth “the deadliness of doing.” There seems no end to this paradox of practical life, and no way out, just an infinite succession of efforts, all doomed ultimately to fail.

Except, of course, there is the option of a spiritual reconciliation to this futility, an attempt to transcend the unending cycle of impermanent human achievement. There is a recognition that beyond mere doing, there is also being; that at the end of life, there is also the great silence of death with which we must eventually make our peace. From the moment I entered a church in my childhood, I understood that this place was different becauseit was so quiet. The Mass itself was full of silences — those liturgical pauses that would never do in a theater, those minutes of quiet after communion when we were encouraged to get lost in prayer, those liturgical spaces that seemed to insist that we are in no hurry here. And this silence demarcated what we once understood as the sacred, marking a space beyond the secular world of noise and business and shopping.”

The inability for technology to really scratch the haunting itch of the loss of the transcendent, that it doesn’t truly ‘enchant’ our world or make our lives feel magical, has fuelled technologist David Rose, who’s committed to creating enchanting technology because he thinks most technology doesn’t live up to the Arthur C. Clarke quote, he wrote a book called Enchanted Objects trying to articulate a vision for the sort of technology that might do this, it’s a compelling read, particularly (I think) for this analysis on the problem with the ideas that screens can deliver the enchantment Telstra promises.

“I HAVE A recurring nightmare. It is years into the future. All the wonderful everyday objects we once treasured have disappeared, gobbled up by an unstoppable interface: a slim slab of black glass. Books, calculators, clocks, compasses, maps, musical instruments, pencils, and paintbrushes, all are gone. The artifacts, tools, toys, and appliances we love and rely on today have converged into this slice of shiny glass, its face filled with tiny, inscrutable icons that now define and control our lives. In my nightmare the landscape beyond the slab is barren. Desks are decluttered and paperless. Pens are nowhere to be found. We no longer carry wallets or keys or wear watches. Heirloom objects have been digitized and then atomized. Framed photos, sports trophies, lovely cameras with leather straps, creased maps, spinning globes and compasses, even binoculars and books—the signifiers of our past and triggers of our memory—have been consumed by the cold glass interface and blinking search field. Future life looks like a Dwell magazine photo shoot. Rectilinear spaces, devoid of people. No furniture. No objects. Just hard, intersecting planes—Corbusier’s Utopia. The lack of objects has had an icy effect on us. Human relationships, too, have become more transactional, sharply punctuated, thin and curt. Less nostalgic. Fewer objects exist to trigger storytelling—no old photo albums or clumsy watercolors made while traveling someplace in the Caribbean. Marc Andreessen, the inventor of the Netscape browser, said, “Software is eating the world.” Smartphones are the pixelated plates where software dines. Often when I awake from this nightmare, I think of my grandfather Otto and know the future doesn’t have to be dominated by the slab. Grandfather was a meticulous architect and woodworker. His basement workshop had many more tools than a typical iPad has apps…”

… Today’s gadgets are the antithesis of Grandfather Otto’s sharp chisel or Frodo’s knowing sword. The smartphone is a confusing and feature-crammed techno-version of the Swiss Army knife, impressive only because it is so compact. It is awkward to use, impolite, interruptive, and doesn’t offer a good interface for much of anything. The smartphone is a jealous companion, turning us into blue-faced zombies, as we incessantly stare into its screen every waking minute of the day. It took some time for me to understand why the smartphone, while convenient and useful for some tasks, is a dead end as the human-computer interface. The reason, once I saw it, is blindingly obvious: it has little respect for humanity. What enchants the objects of fantasy and folklore, by contrast, is their ability to fulfill human drives with emotional engagement and élan. Frodo does not value Sting simply because it has a good grip and a sharp edge; he values it for safety and protection, perhaps the most primal drive. Dick Tracy was not a guy prone to wasting time and money on expensive personal accessories such as wristwatches, but he valued his two-way wrist communicator because it granted him a degree of telepathy—with it, he could instantly connect with others and do his work better. Stopping crime. Saving lives.

— David Rose, Enchanted Objects

He looked to our ‘enchanted’ stories; stories that have the sort of view of the world that Lewis (and his friend Tolkien) looked back to from the past and created in the more recent past… but it’s possible he missed the heart of what these writers (and J.K Rowling) were doing.

What’s the secret to creating technology that is attuned to the needs and wants of humans? The answer can be found in the popular stories and characters we absorb in childhood and that run through our cultural bloodstream: Greek myths, romantic folktales, comic book heroes, Tolkien’s wizards and elves, Harry Potter’s entourage, Disney’s sorcerers, James Bond, and Dr. Evil. They all employ enchanted tools and objects that help them fulfill fundamental human drives.

He does understand that technology will only work if it speaks to fundamental human desires; he’s not going to these stories as books containing “fanciful, ephemeral wishes, but rather persistent, essential human ones,” which he lists as omniscience, telepathy, safekeeping, immortality, teleportation, and expression. Basically, to use Taylor’s terminology, we’re in want of something that will pull us from the immanent into transcendence. Rose does just enough to kill Telstra’s claims that connectivity via a piece of glass can give us what our haunted hearts desire, and the technology he writes about as alternatives, like a magic cabinet that has a built in screen with a skype connection to a matching cabinet, which glows when the person at the other end of the line is nearby and allows instant and convenient conversation; well, that’s pretty great and does fan some of the flames of my heart (and could one day make my wallet lighter). The problem will always be that immanent objects — the product of coding and engineering — will only ever leave us trapped in the immanent world, the ‘brass heaven,’ haunted by a sense that there might be something more to life and relationships than that which can be encoded in bits and bytes made up of 1s and 0s. The problem will always be that eternity is written on our hearts; if only, like the writer of Ecclesiastes, we knew where to look to scratch that itch. This writer, who after his journey through life trying to sort the immanent out from the transcendent, concluded:

“So I reflected on all this and concluded that the righteous and the wise and what they do are in God’s hands, but no one knows whether love or hate awaits them. All share a common destiny—the righteous and the wicked, the good and the bad, the clean and the unclean, those who offer sacrifices and those who do not.” — Ecclesiastes 9:1-2

He doesn’t take this to the negative sort of place you might expect…

“You who are young, be happy while you are young,

and let your heart give you joy in the days of your youth.

Follow the ways of your heart

and whatever your eyes see,

but know that for all these things

God will bring you into judgment.

So then, banish anxiety from your heart

and cast off the troubles of your body,

for youth and vigor are meaningless.Remember your Creator

in the days of your youth,— Ecclesiastes 11:9-12:1

Then he says:

“Remember him—before the silver cord is severed,

and the golden bowl is broken;

before the pitcher is shattered at the spring,

and the wheel broken at the well,

and the dust returns to the ground it came from,

and the spirit returns to God who gave it.”— Ecclesiastes 12:6-7

This is what we’re to do in our ‘immanent’ existence; the fleeting ‘breath’ that this writer reflects on time and time again that is unfortunately often translated as ‘meaningless’… we’re meant to reach out towards the God who gave us breath, knowing that as he puts it at the start of his summing up in Ecclesiastes 9: “the righteous and the wise and what they do are in God’s hands“… now… If only we knew where to look to see God’s hands. If only there were some way to scratch where we itch… if only there were some way to bridge between the immanent and the transcendent; to satisfy those deep desires that the writer of Ecclesiastes, Telstra and David Rose are searching for — the ability to see the world as meaningful beyond the material, to give us existence beyond ‘breathiness’ so that we become immortal.

Oh that’s right. According to two thousand years of Christians, and the book we live by… We do.

Paul says some more good stuff about Jesus in Colossians 1; about the implications of that time we see the hands of God; hands nailed to ugly planks of wood by barbaric spikes, these hands Paul says hold the cosmos together became very ‘immanent’ and are the ultimate enchanted objects that deliver on our wildest imaginings. Paul says:

“And he is the head of the body, the church; he is the beginning and the firstborn from among the dead, so that in everything he might have the supremacy. For God was pleased to have all his fullness dwell in him, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether things on earth or things in heaven, by making peace through his blood, shed on the cross.” — Colossians 1:18-20

That’s more magical than an iThing (as nice as they are) don’t let Telstra, or anyone, sell you short. You can enjoy the sort of life you so deeply desire and are haunted by. You can enjoy life that is more than just immanent, more than just heading towards the dust of the grave, you can enjoy life that’s more than a little bit magical.