Rugby Australia’s Inclusion Policy, published in 2014, is specifically designed to ensure LGBT+ people are included in the rugby community, and especially on the field as participants in that community.

Rugby Australia’s goals, as stated in the policy, are:

“Rugby AU’s vision is to ignite passion, build character and create an inclusive Australian Rugby community. Our vision can only be achieved if our game is one where every individual participant, whether players, officials, volunteers, supporters or administrators feel safe, welcome and included.”

And so, the Inclusion Policy codifies ‘inclusion’ as ‘freedom to participate… without fear of exclusion’ — and broadens the focus beyond sexual orientation to include gender, race, and religion.

“Rugby AU’s policy on inclusion is simple: Rugby has and must continue to be a sport where players, officials, volunteers, supporters and administrators have the right and freedom to participate regardless of gender, sexual orientation, race or religion and without fear of exclusion. There is no place for homophobia or any form of discrimination in our game and our actions and words both on and off the field must reflect this.”

It’s perhaps a sad thing that the history of sport is littered with examples of exclusive policies around exactly these categories; this sort of policy is, in the face of history, a necessary policy. It ensures people can gather around a common object of love — Rugby — and form a community.

Theologian Oliver O’Donovan wrote a book called Common Objects of Love unpacking a bit of the philosopher/theologian Augustine’s thinking around how shared loves build communities, and how these communities are a necessary part of our social fabric — they bring together people who are different in a certain sort of unity. O’Donovan (building on Augustine and before him, Cicero), defined community as: “a multitude of rational beings united by agreeing to share the things they love.”

Note, this doesn’t say anything about the areas where we don’t agree, or where we have different loves, it holds out the hope that a ‘common unity’ might foster the coming together of a multitude; and when this happens it is both good and beautiful. When Muslims and Christians set aside difference and take the field together as opponents with a shared love of a game, or even better, as a team, great things happen. I’ve witnessed that first hand in the football league I play in in Brisbane. One of the first things I talk about when meeting refugees or asylum seekers in Brisbane is our shared love of sport — even if they’re Real Madrid or Arsenal fans — but there’s evidence beyond my particular experience. When Israeli and Palestinian children take the field together through a program run by a group called Mifalot, this produces real changes in attitudes towards the other, through that shared experience. So after participating in a program, and being surveyed:

-

Among the Palestinian children, a 35% increase in trusting all or most Jewish Israelis, a 23% increase in hating none or almost no Jewish Israelis, and a 22% increase in thinking that none or almost no Jewish Israelis hate Palestinians.

-

Among the Jewish children, there was a 20.5% increase in those who trust all or most Palestinians, a 16.5% increase in those hating none or almost no Palestinians, and a 17% increase in thinking that none or almost no Palestinians hate Jewish Israelis.

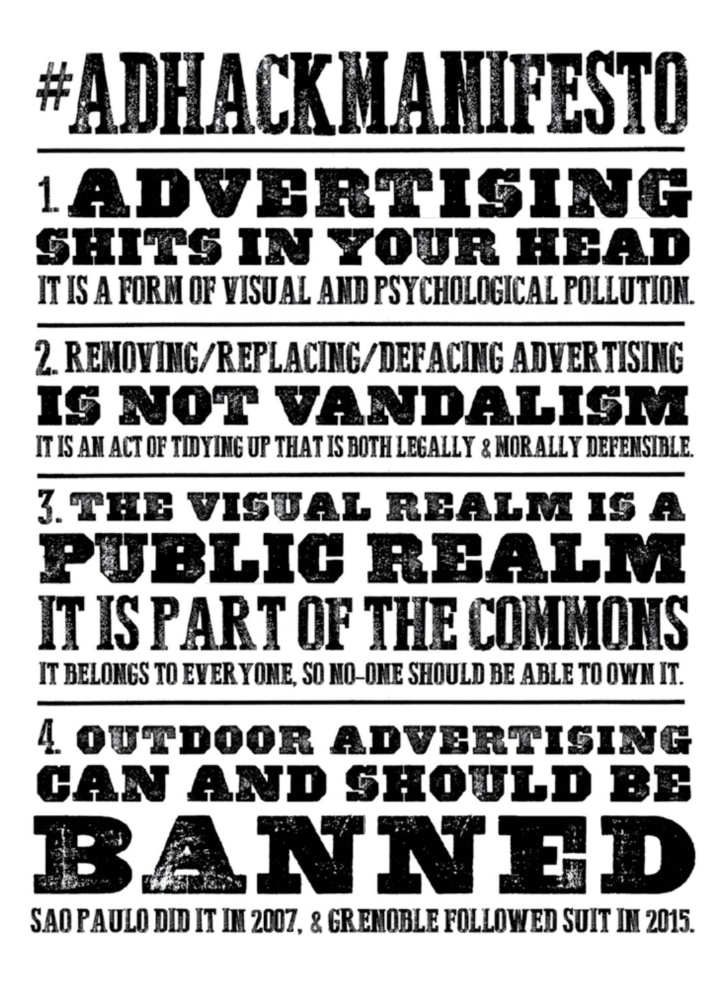

The ‘commons’ being inclusive, or holding common what can be held in common, while other things might divide us, is a vital thing for human flourishing; and arguably, for the reduction of exactly the sort of issues Rugby Australia seeks to eradicate with its Inclusion Policy. If Rugby Australia was to hold to a robust, generous, pluralism that allowed people who have different views and backgrounds to take the field together around a shared love of Rugby, that wouldn’t just be good for the individuals involved, but for the people the players selected for those teams ‘represent’ (on the power of ‘representation’ consider Black Panther or Wonder Woman and the impact those movies had).

How our ‘common’ or public institutions function has real potential to shape the way we interact with one another around loves we do not share.

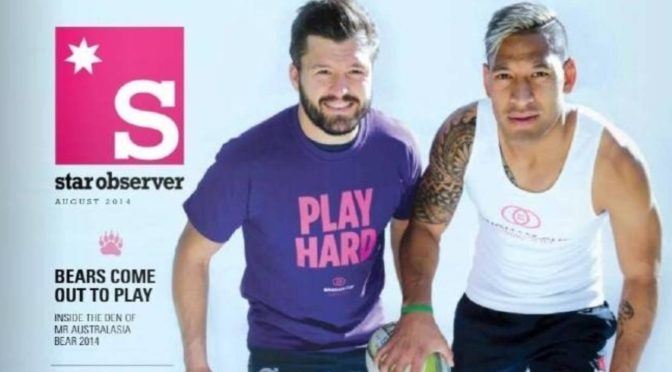

The problem we’ve seen in the Israel Folau case is that inclusivity runs into a bit of trouble if the ‘common objects of love’ aren’t clearly defined and limited (ie rugby), or if the ‘centre’ — the shared love — of the community changes in such a way that it excludes people it claims to be including such that, perhaps, rugby becomes a means to the ends of inclusion, rather than inclusion being the means to the shared ends of rugby. In Folau’s case, potentially, someone who, from a ‘religious object of love’ has expressed a different moral position on homosexuality in that sphere/love (ie the religious sphere), the question is then how inclusion is defined. If the inclusivity platform seeks to go beyond the shared love, it is no longer aimed towards community (a common unity) but something else; and if the insistence is that LGBT+ players will not feel safe or welcome with players who hold religious convictions (about supernatural, spiritual, matters like heaven and hell) that don’t impact that individual’s approach to the Rugby field, or community, then this is a problem that must surely lead to an amendment of the Inclusion Policy to exclude religion as a protected category. It’s clear that, in this case, these religious views do not stop the individual in question being prepared to take the field with, or support the inclusion of LGBT+ athletes on the Rugby field — Folau was a former face of the Bingham Cup, described as “the biennial world championships of gay and inclusive rugby,” tournament organisers said he was a “strong advocate for ending all forms of the discrimination in sport.” It seems to me that Folau is better able to embody the inclusion policy of Rugby Australia than the leaders of Rugby Australia.

Here’s the perennial disclaimer I include in every Folau post — I think his social media comments were irresponsible, as a fellow Christian his views on the way the good news of Jesus should be articulated, and probably on what the Bible prohibits in the passages he mashes up on Instagram, are fundamentally at odds with mine. The Bible had no conception of ‘homosexuality’ as an orientation or identity; this is a relatively modern development of ‘identity’ built from desire; it does, however, provide a framework where our ‘chief’ or ‘ultimate’ love will shape the way we use our bodies in relationships and sex, and it prohibits same sex sex. This is to say, I wouldn’t say ‘homosexuals’ are condemned on the basis of identity, orientation, or attraction, but like all people, we stand forgiven or condemned based on what we do with Jesus, and whether we hold the God who made the universe as the chief, defining, organising love of our life; ie whether we worship him. I note, having chatted to a friend this morning, that it’s interesting that a bloke with a $4 million contract posted a meme that omitted greed from the list of sins that lead to hell… and that this is a bit of a blind spot in our Christian culture, that we’re happy for a champion to say hard things about sexuality, but we’ll give him, and each other, a pass on how we approach money. I think, if reports of his contract and agreements with Rugby Australia are correct, they’ve got good grounds to terminate his contract.

While I disagree vehemently with Folau, I’d still ‘take the field’ with him if I could tolerate Rugby Union (and if I had the ability; a national sporting body has to draw a line somewhere). This is because communities built around common objects of love are necessary not just for finding common ground, and reminding ourselves of our shared humanity, but because relationships built on connection and trust are also vital for having the sorts of conversations that will change attitudes and hearts.

Rugby Australia needs to decide if it is a public organisation or institution, or a private business. It needs to decide what ‘good’ it is pursuing in its vision and what ‘inclusive’ really means. It needs to decide if, as a private business, it must make decisions based on what is commercially beneficial, or as a public institution, it must make decisions about what sort of society it imagines, and what sort of virtue or character it wants to build. It has a real chance to lead Australia towards a generous picture of community; where people feel safe and welcome even while disagreeing in other spheres; where deep and significant conversations can take place face to face, amongst embodied humans — rather than disconnected conversations happening where we are mediated to one another as pixels, and where it is so easy to dehumanise and shout past one another. Rugby Australia has to ask itself if it wants to exclude Folau because he failed to ‘represent’ a version of an ideal (held by the powerful), or if in excluding him they also set an exclusive standard that might ultimately trickle down and exclude all those who hold his views who are lacing up their boots and taking the field next to LGBT+ players all over the nation, sharing a love of rugby, and building the sorts of relationships and connection that change hearts about one another across things that divide. The media needs to ask itself if trotting out condemnation after condemnation from Folau’s teammates actually reinforces the sort of ‘exclusivity’ that is ultimately damaging from the grassroots up, not just the top ‘ideological champion’ representative players down.

There are significant dangers with exclusivity — and these are dangers Christians need to stare down in places where we run the show. Firstly, when the parameters for exclusivity are set by the powerful, on their own terms, the inclusivity isn’t genuine, it’s colonisation; it requires people to be included on terms other than their own. This is where I suggested the Folau furore, and his condemnation by ideologically drive, white, upper management types, is a bit racist. One must, when seeking to include LGBT+ members in a community, consult and understand what it is that leads those individuals to feel unsafe; what homophobia looks and feels like, and what the gay experience involves; one hopes the leaders of Rugby Australia have done that work, that they are framing inclusivity in the interest and from the experience, of the outsider or minority… but this is true for all forms of inclusivity; one hopes they’re also consulting women about what inclusivity in an historically male sport would look like, ethnic minorities about inclusion in a sport that has been the property of exclusive, typically white, private school education in Australia’s sporting class war, and, people with religious convictions about the nature of religious conviction — of loves other than Rugby, and how they cascade in to the approach people take to Rugby. It’s tricky in a culture where sport often occupies the chief place in the heart of the Australian, or a space that competes with other loves, to conceive of itself as something other than an ultimate love, but an inclusivity program that recognises that people aren’t rugby players or members of the rugby community first, but come to this ‘common ground’, the rugby field, from other spheres is a good start.

The second danger of exclusivity is one that should be familiar to people in the Rugby fraternity — when you exclude a certain class of people from taking the field under your rules, they set up a parallel (and in the case of Rugby League, superior) field. Community fragments when you try to broaden what people are gathering around from a common love, to contested loves. And fragmented community is not a great thing where common grounds might exist (unless, like me, you believe League is superior to Union). In my submission to the Ruddock Review of Religious Freedom, just as in my response to the Benedict Option, a book championing a form of Christian withdrawal into parallel communities, I suggested that the last thing we want in our shared, civic, public, life is for people who disagree to further withdraw into exclusive communities built around not just common loves, but common dislikes. This is part (but not all) of how we get contemporary Christian music, Christian schools, and all manner of parallel institutions (including Rugby League). Rugby Australia, in adopting a more exclusive approach, runs the risk of those it excludes forming (or joining) alternative ‘fields’ where they might seek a more radical inclusion, but are more likely, on the basis of human nature, to be equally exclusive and to lead to more fracturing of our common life, more polarised convictions, and more conflict. The problem with setting up ‘exclusivity’ in the public field, or commons, is the same problem Christians are now running into because we tried to be ‘exclusive’ with our definition of marriage; it sets up a ‘zero sum’ game where the disenfranchised party no longer seeks compromise in relationship, but victory at the expense of the other. And it builds a cycle of resentment, rather than peacemaking, which builds the conditions that allow common love, fraternity, and persuasion in pursuit of goodness and truth.

Our national rugby team represents a vision of the sort of society we hope to be as a nation. The players who take the field are our ‘representatives’; and so the approach Rugby Australia takes to its vision is more important than some of us might like to think, but perhaps, less important than they’d like it to be (if they’re pursuing an ideology in a zero sum way, and people can just take their ball, and participation, elsewhere). Rugby Australia is, at a micro level, facing the same challenge that our nation’s leaders are facing as they work out ‘religious freedom’ and what that means in a contested landscape. So, as my submission to the Ruddock Review said, “surely the best future for our nation is one where our diversity produces richness and resilience through civil disagreement and tolerance, rather than a fragmented nation where different communities withdraw into their own bubbles such that we are able to find less and less in common; less to unite us as citizens?”