Flannery O’Connor once told a young friend to “push as hard as the age that pushes against you.” The church is to be a radically alternative people, marked by the love of the triune God in each area of life. — Tish Harrison Wells, Liturgy Of The Ordinary

This is the final (probably) post in this series contemplating what it looks like to see the church as being a worshipping community at war with the ‘gods’ who compete with God for our love and worship. It suggests winning that war is about sharing practices that orient us towards the love of God we find in the Gospel; so that our love for God prevents us loving other gods; both by pushing them from our hearts, and then by occupying them.

In my last post I suggested these practices should be built from Romans 12’s description of worship, and the sort of shared life we find in Acts 2 (and the early church); and that somehow this is perhaps descriptively liturgical rather than prescriptively Liturgical. I’m wanting to take on board much of the recent work of James K.A Smith (in his Cultural Liturgies series), and more recently Tish Harrison Wells in Liturgy Of The Ordinary, without totally swallowing their suggestion that the answer to the worship wars is capital-L ‘liturgy’; the ‘traditional forms’ of the church’s worship (which to me feel like the medieval forms of the church’s worship, or perhaps the forms of the church’s worship detached from the 24/7 rhythms that supported those forms in Acts 2). I think the 24/7 rhythms of the church in Acts 2 were the ‘ethos’ that gave life and plausibility to the ‘liturgy’ of the early Sunday service, not the other way around (but that’s probably a false dichotomy); whereas I feel like Smith and Wells see it the other way; where the Liturgy on a Sunday feeds into the rhythms of the week.

I suggested the picture of the church community who held everything in common and met every day is the sort of ‘worship’ that I see helping win the worship war; that that’s the sort of context in which we can be formed and forged into people who will love God and hate idols. Or love God, and so have our love for the good things he made properly ordered… That picture excites me.

The sort of Liturgical life Smith and Wells invite me to pursue doesn’t.

This is all meant to be about shaping our loves; but I just don’t love that way. This is where I suspect some of my discomfort with Smith and Wells and their push for a liturgical life kicks in. Personally I find the whole liturgy thing a bit boring; it doesn’t mesh with who I am, it doesn’t float my boat or fire my heart, or stoke my imagination. I know it should, and it’s a discipline, and that discipline might actually help me relate to people not like me. But when I read Smith (and to a lesser extent Wells) I love the system of thinking but loathe the application…

But here’s the thing; this vision of the Romans 12/early church picture sounds ideal and refreshing to me; but it sounds like something that would exhaust my introverted wife. If this is how the ‘worship wars’ must be fought, then I’ll be an early casualty; but, if they’ve totally got to be fought on my terms, in a shared life, open home, messy hospitality, constant-presence-in-the-ups-and-downs-of-life, reflecting-the-gospel ‘sacrifice,’ then my wife will be an early casualty; and either way we (our family) lose.

So here’s my thesis…

Worship needs to be all of life in a way that takes me as I am and uses the ‘gift’ I am in my renewed-createdness for the sake of others, in service of the gift-giver.

And part of that means acknowledging that my createdness; and the best of me; looks different to the createdness of others. This means the liturgy will look and feel a little different for all of us; while being geared towards the same ends (the benefit of the body, the demonstration of the Gospel, and the cultivation of our love for Jesus). In pushing for a single ‘form’ of liturgy, Smith advocates a one-size-fits-all for all time liturgy. I think that runs the risk of de-humanising those who don’t love like he loves. Wells is a useful additional voice on this because she’s exploring how Smith’s stuff, and a love for Liturgy, shapes the every day.

I do love the way she does this; she takes the structure of a Liturgical service and reframes everyday activities like making the bed, showering and cleaning your teeth, fighting with your family, losing your keys, being stuck in traffic, drinking tea, and sleeping as things that can teach us our story.I really like the way Wells writes; and the way she breaks down the secular/sacred divide by taking up this ‘worship-is-love-shaped-by-habit’ framework… but often it’s just not corporate enough for little extroverted me. It’s fantastic. I love her stuff on Romans 12 that reflects on how it’s all about embodiment; and I think this is powerful when paired with the plural your in the verse she’s writing about:

I needed to be trained to offer my body as a living sacrifice through my body. We learn how our bodies are sites of worship, not as an abstract idea, but through the practice of worshiping with our bodies. Each day our bodies are aimed toward a particular end, a telos. The way we use our bodies teaches us what our bodies are for. There are plenty of messages in our culture about this. The proliferation of pornography and sexually driven advertising trains us to understand bodies (ours and other people’s) primarily as a means of conquest or pleasure. We are told that our bodies are meant to be used and abused or, on the other hand, that our bodies are meant to be worshiped. If the church does not teach us what our bodies are for, our culture certainly will. If we don’t learn to live the Christian life as embodied beings, worshiping God and stewarding the good gift of our bodies, we will learn a false gospel, an alternative liturgy of the body. Instead of temples of the Holy Spirit, we will come to see our bodies primarily as a tool for meeting our needs and desires. The scandal of misusing our bodies through, for instance, sexual sin is not that God doesn’t want us to enjoy our bodies or our sexuality. Instead, it is that our bodies—sacred objects intended for worship of the living God—can become a place of sacrilege. When we use our bodies to rebel against God or to worship the false gods of sex, youth, or personal autonomy, we are not simply breaking an archaic and arbitrary commandment. We are using a sacred object—in fact, the most sacred object on earth—in a way that denigrates its beautiful and high purpose…

But when we use our bodies for their intended purpose—in gathered worship, raising our hands or singing or kneeling, or, in our average day, sleeping or savoring a meal or jumping or hiking or running or having sex with our spouse or kneeling in prayer or nursing a baby or digging a garden—it is glorious, as glorious as a great cathedral being used just as its architect had dreamt it would be.

This is terrific stuff; I just want to say “yes… and”… and this ‘and’ is part of me trying to articulate where I feel both Smith and Wells sell us a little short in their conclusions about worship (and I want to stress this is perhaps as an extrovert with, as Myers Briggs puts it, an emphasis on ‘intuitive’ processing of the world). It all feels a little bit introspective, or seeing worship predominantly in a vertical ‘God-Me’ frame; where it could be more horizontal and vertical in a ‘God-Us’ frame…

So this stuff about the body from Romans 12 and 1 Corinthians 6-10 is great, but Paul’s logic about the body in 1 Corinthians isn’t just that our bodies belong to God; though they do; it’s that via our union with Christ our bodies belong to each other; not in a way that totally does away with bodily autonomy so that I have to give me to anyone who wants me, however they want, but in a way that stops me using my body for idol worship/sexual immorality (and in a way that my body does belong sexually to my spouse and me). This fits with the plural in Romans 12 too…

And here’s an itch I just can’t scratch when it comes to both Wells and Smith; something that just doesn’t sit quite comfortably on my creaturely shoulders; though I’m sure their push for Liturgy and liturgical calendars, and tradition, and imagery, and structure, works for others. But for me — and this is largely ‘personal preference’ and intuitive pushback, I’d really like a book on imagining the kingdom to leave more room for the imagination (while acknowledging that our imaginations will be fired in helpful directions by totally different sorts of stimulus). I feel like Paul is pretty descriptive when it comes to what embodied corporate worship should look like (in both Romans 12 and 1 Corinthians 12-14); but the jump to big-L Liturgy feels a bit prescriptive to me. There’s lots from You Are What You Love and Liturgy Of The Ordinary that I’ll take on board; some of it because the idea of incorporating the ideas into the rhythms of my life with my family and church seems usefully formative, and some of it precisely because it grates, and in grating, it might push me to a different sort of formation that will be more beneficial to others (especially my family). But not all of it… where Smith seems to give permission for some innovation around his insights about worship, while making the case for most of our ‘rhythms’ to be set Liturgically, I want to say Liturgy might play some part in our worship, but I don’t think I can rely on it in quite the same way he does; and I suspect this is true for a host of people like me. It’s ironic how much what follows is built around ‘I want’… but we’re talking about what it takes to calibrate our hearts in a particular direction, so there’s something intensely personal about this. I want to take the descriptive stuff on corporate worship and ‘formation’ in Romans 12, Colossians 3, and 1 Corinthians 12-14 and play with it using my imagination; not just for my sake, but for the sake of being a rich and diverse community that accommodates people in their difference.

I want worship that feels like it is reinforcing our corporate reality; not just my own relationship with God, but ours; that acknowledges the horizontal as well as the vertical, that isn’t just corporate by virtue of me going to the spiritual gym next to a bunch of other ‘worshippers’ on Liturgical-treadmills (and we can’t escape the corporateness of the sacraments or ‘Liturgy’ anyway), but that is corporate because the essence of worship-as-ritual is corporate. Again, it’s hard to say Smith and Wells don’t want exactly the same thing; there’s always a corporateness to what they write. What I suspect I’m reacting against is an approach to a paradox that doesn’t quite emphasise what I most naturally do… Perhaps because I’m extroverted, though perhaps simply because I lean this way as a corrective to a society that has gone too far in the other direction; I want to emphasise our ‘corporateness’ above our individualness when thinking about worship. I want my practices to be corporate much more than individual. I want ‘noisy time’ not ‘quiet time’… the paradox of our existence is that we’re both individual and individuals-in-relationship.

I’m human; and that necessarily means there’s a corporate element to my creatureliness. I want to do all this stuff she imbues and enchants with sacred, Gospel, truth, but start with the default assumption that I’m a person-in-relationships, not a person-then-relationships. I’m a son before I’m even conscious of my existence, a husband in a ‘one-flesh’ relationship by vow and practice, and a father before my kids know it… not to mention a child of God. I’m defined by my relationships as much as by my individuality be that the way my body, mind and soul work, or the products of those pieces of me: my personal narrative, loves, habits, desires and imagination. My relationships shape those things too — whether by nature or nurture. My habits are caught, mostly, and they infect… or they’re things I do with others (things ‘we do’). As I read these great books I feel like they’re telling me to work on getting new habits, and while the solution is corporate it’s about participating in shared capital-L liturgy with others; when the small-l liturgies are where 97% of the week is lived.

That’s where the Acts 2 picture of worship as sharing ‘everything in common’ ‘every day’ has so much power. There is, of course, a corporate element to everything both Smith and Wells talk about, it’s really just a vibe thing; one little example is this epiphany I had as I read Wells talk about thankfulness; thankfulness is a thing we’re encouraged to do in Colossians 3 (amongst other places), and it’s a discipline I’ve been practicing on social media this year. It has been helpful. But it occurred to me that the thankfulness in Colossians 3 is corporate; it’s celebration; it’s thankfulness not just about the good in my life, but ‘rejoicing with those who rejoice’ even if I feel more like mourning.

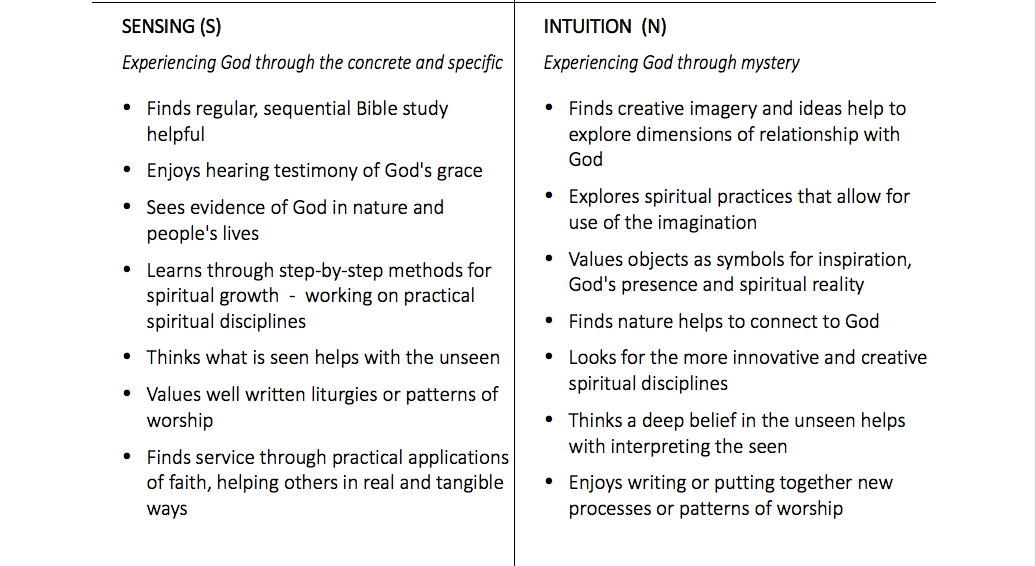

I’d been scratching this itch for quite a while before I went through this document called ‘personality and type’ with my mentor; he was challenging me to cultivate spiritual disciplines that don’t just fit with my personality type, and gave me a document called Looking at Type and Spirituality that suggests (based on the Myers-Briggs types) that different types of ‘habit’ or different ways of seeing the world will come more naturally to different people. I’m pretty sure the document is one he’s paid for, and is under copyright, but here’s a snapshot of one comparison between two different types… Notice “values well written liturgies or patterns of worship” and “enjoys writing or putting together new processes or patterns of worship”… I’m an “F”… My guess is that Smith and Wells might both be Ss.

I don’t know how much weight to put on Myers-Briggs personality stuff; but what I do know is that people are different, and we get excited about different things, and God created and accommodates those differences (and sin/idolatry works differently for different sorts of people); and what we really need if we’re going to be an Acts 2 type community is not to mandate types of worship that fit our particular personality and experience; but find ways to be a community that is rich because it provides ‘rituals’ that help different people cultivate their love for Jesus.

It’d be a real shame to take this sort of insight and say ‘Liturgical churches will reach S-types while non-Liturgical churches will cater to the N-types”… if everybody worshipped the same, we’d get tired of worshipping with each other; and we wouldn’t be doing the Romans 12 thing of learning to live together as a diverse body.

I know there are quite a few people in our church community who are much more Liturgical than I am and that my wife and children operate differently to me… When it comes to our church community; some enjoy Advent, others love old church architecture, some pray through the Prayer Book, others want our sacraments to be more beautiful. It’s not loving for me to set rhythms that don’t help them love Jesus. And if I choose to be ‘not loving’ then I’m actually not ‘worshipping’ in the Romans 12 sense… Because worship is ultimately about love it’s also about understanding and listening; first listening to and understanding God, but in turn, because God calls us to sacrificially love others, it’s about listening to and understanding others and how they tick and sacrificing on their terms, not my own. That’s why I’ll heartily endorse Smith and Wells and try to get everyone I can to read their books (especially Liturgy Of The Ordinary and You Are What You Love). They have given me some insight into the value of those practices I am inclined to toss because they do ‘nothing for me’… but because I see the benefit to others, and have perhaps even been convinced of the beauty of some structure (especially by Wells), there are Liturgical practices in those books that I hope to take up. I’ll do so both to push myself beyond my comfort zone, but also in order to love others better so they might love Jesus more (which in turn will shape my love for Jesus). There are also liturgical practices that I hope will shape our community in such a way that it makes loving Jesus more plausible for people who are wired to be like me…

That’s how I live out the truth that I am both ‘me’ and ‘me-in-relationships’ — that my body is God’s, but also belongs to others…

The challenge for those of us who have a hand in shaping the culture and rhythms of church, and family, life is to do it in a way that caters for the other; and that might involve participating in ‘Liturgy’ or ‘ritual’ that doesn’t float your boat, because that, in itself, is an act of sacrificial love for the other, and so, whether you like it or not, it’s worship.