The Presbyterian Church of Queensland is in a state of transition. We are still in receivership — though the matter that put us there is now before the courts (this week, and maybe for the next few years…).

Those responsible for leading us into receivership — and their cohort — have almost entirely stepped out of official leadership roles — whether that’s in office bearing capacity, committees, or denominational staff. There has been an amount of soul searching in moments where it looked like we might lose everything, and a number of reviews on our practice and culture, and even an attempt to articulate a theology of the church.

There are a number of lines of tension within the denomination as the chips fall and people grapple for places at various tables and to have their views on culture, practice, or theology embedded in our realigned structures.

It has been fascinating for me, personally, trying to account for how different points of conflict and agreement with different people — my own position — shaped, in part, by my own experiences and convictions is quite different to that of fellow members of courts and committees of the church. And I’ve been struggling to articulate how I can find myself in furious agreement with some folks on one issue, and then diametrically opposed on another.

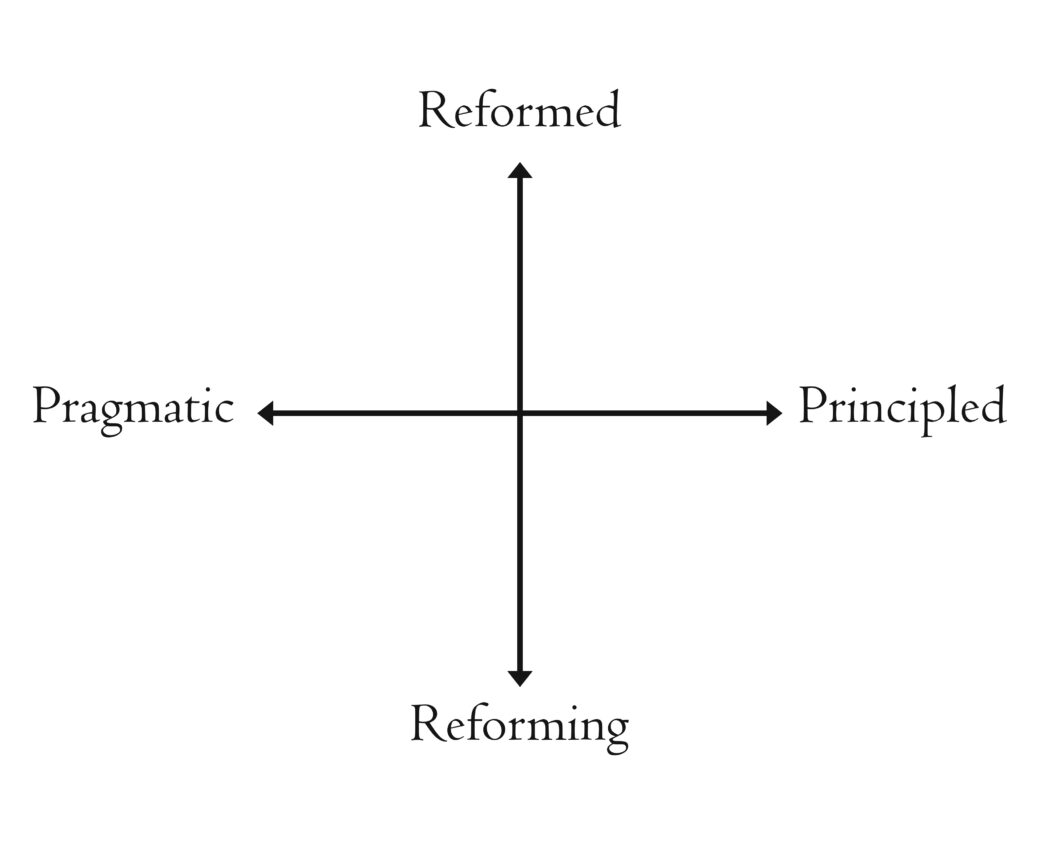

So I started trying to unpack a little of what is going on. My first attempt at mapping out the differences was a two dimensional ‘compass’.

The two axis of this compass represented two spectrums that are at work in the Presbyterian Church — and maybe in other Reformed evangelical churches. The up down axis I have recognised for a while; I’ve described it as a tension or spectrum between the Reformed and the Reforming.

The Reformed — particularly in the Presbyterian Church of Australia (not just Queensland) are Presbyterians by conviction; committed to the Westminster Confession of Faith in full. They tend to view the Declaratory Statement as a weakness undermining the confessional Reformed faith. When an issue arises they look for clarity in the Confession as a guide; and where the confession is silent, increasingly, they aren’t looking to enact the liberty the Confession itself calls for, but to build out more black and white ‘confession like’ statements of theological consensus for the denomination to adhere to. This is, of course, a spectrum — there are differences along this axis in terms of, for example, the place of the law in the life of the Christian. The above the line end of this pole would also be where Calvinism is located (however one understands the essence of Calvinism), as opposed to Arminianism, though stong identification in the Reforming camp probably captures Calvin (and Luther’s) Spirit.

The reforming, within the denomination, are Presbyterian by convenience. Presbyterianism, with its broad evangelical framework, has, for some time been where you’d go to be a Sydney Anglican (basically) outside of Sydney. If you are, for example, committed to a Christ centered (or Christotelic) Biblical theology (the Bible as a narrative, rather than a rule book), and ministry built around the sort of Bebbington quadrilateral of evangelicalism, you probably land down this end. Presbyterianism is a good boat to fish from to do this kind of ministry. If you face an issue that appears novel, your instinct is to bring the Bible to the task of reforming the theology and practice of the church, rather than turning to the Confession. I think one way this tension along this axis could be described is in the tension that observably exists in theological colleges (especially confessional ones) between the Systematic theology department and the Biblical Studies department.

Some tensions within PCQ, and PCA, are because people occupy different places along this spectrum.

The left-right axis is an emerging tension; I mean, it may have been around for a while, but within the PCQ it is particularly being experienced as a tension between those looking to two groups. On the left hand side we have Reach Australia and its system emphasis, and almost — though they would not like to be described solely this way — its pragmatism. On this side of the spectrum faithfulness is measured in fruitfulness — and that fruit is not so much the cultivation of the fruit of the Spirit in a person, or community of persons, but fruitfulness in conversion. On the right hand side we have our own internal body, created by our Committee for Ministry Resourcing, Healthy Churches, which emphasises personal spiritual health and the idea perhaps (at least as I would express it) of being a faithful presence; committed to cultivating spiritually healthy communities (that are also emotionally and relationally healthy) that offer something different to the world. At its worst, the pragmatic side embodies all of the strategies of the world — ala the Church Growth Movement; at its worst, the healthy church side is totally introspective and not at all interested in tools, techniques, or strategies geared towards (or measuring) outputs or results.

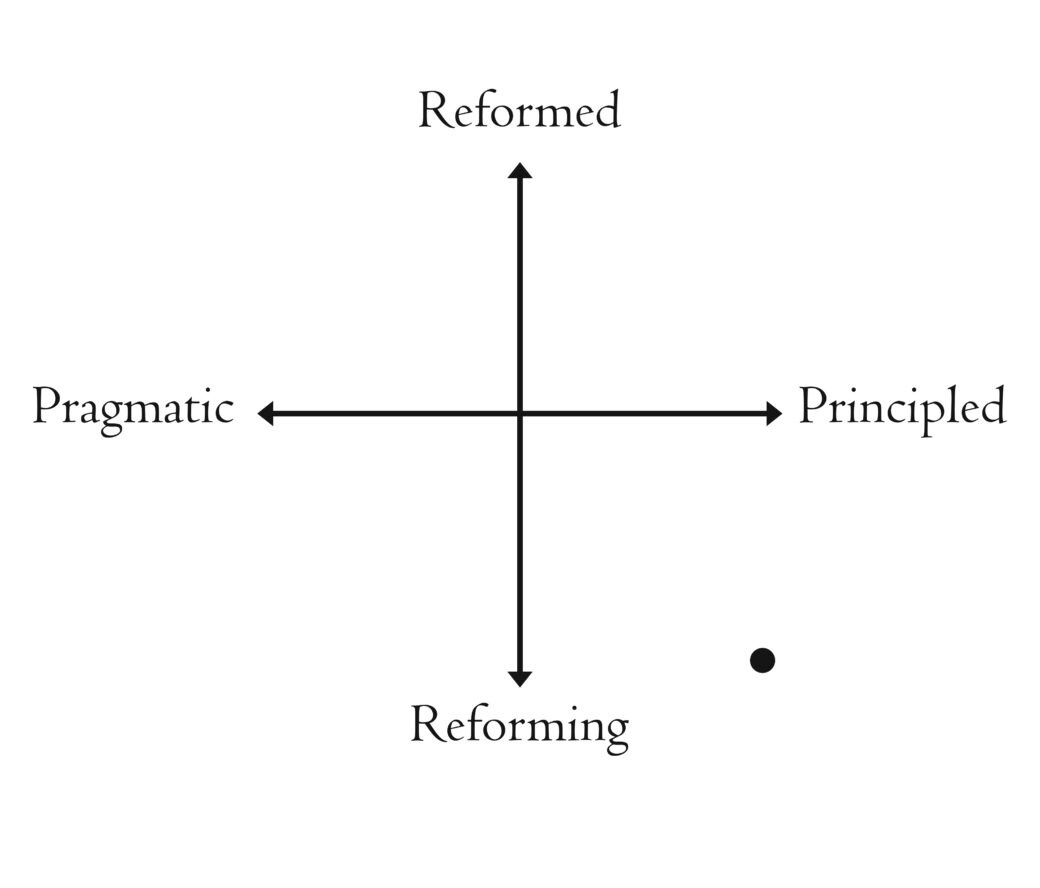

In this initial 2 dimensional compass I was plotting people in various quadrants. Here’s where I would have put myself:

While this had some explanatory power, there was a twofold problem that became clear the more I imaginatively plotted others on the graph, and the more I introduced the schema in conversation with other people from PCQ.

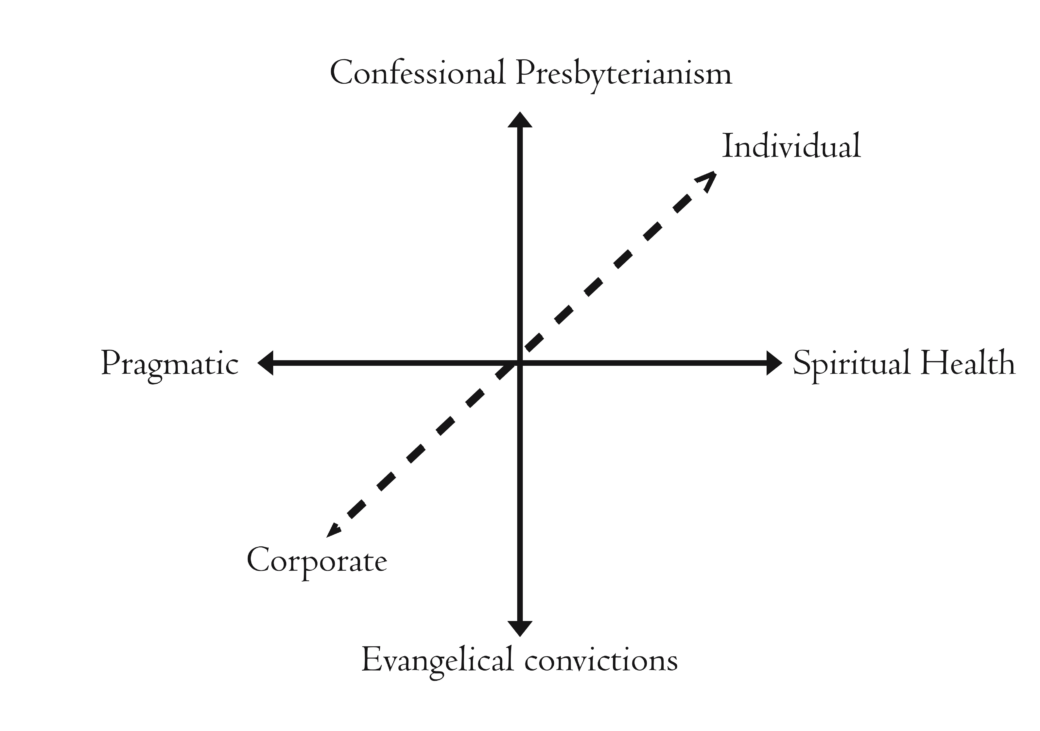

The first problem was that I think there are other axis — another point of tension within our denomination is around the nature of the Gospel itself and, in part, the way this shapes our politics (or engagement in justice versus, say, simply proclaiming the Gospel to secure an individual’s personal salvation (where Salvation is life in a sort of disembodied heavenly future). T

his axis plays out along the debate between an individualised emphasis on penal substitutionary atonement as ‘the Gospel’ and what might best be encompassed by the New Perspective on Paul (but also probably a traditional protestant/Catholic division). I’ve expressed it as ‘individual’ and ‘corporate’ — emphasising salvation in the descriptor of the axis, but our vision of salvation flows into our understanding of morality, ethics, and politics (I’d say some part of the classic ‘left/right’ tension plays out along a systems/individual spectrum).

So I tried to make a 3D graph, where I sit in ‘front of the page’ emphasising the corporate, while many of my brothers and sisters in modernist Reformed protestant churches are committed to a sort of individualism.

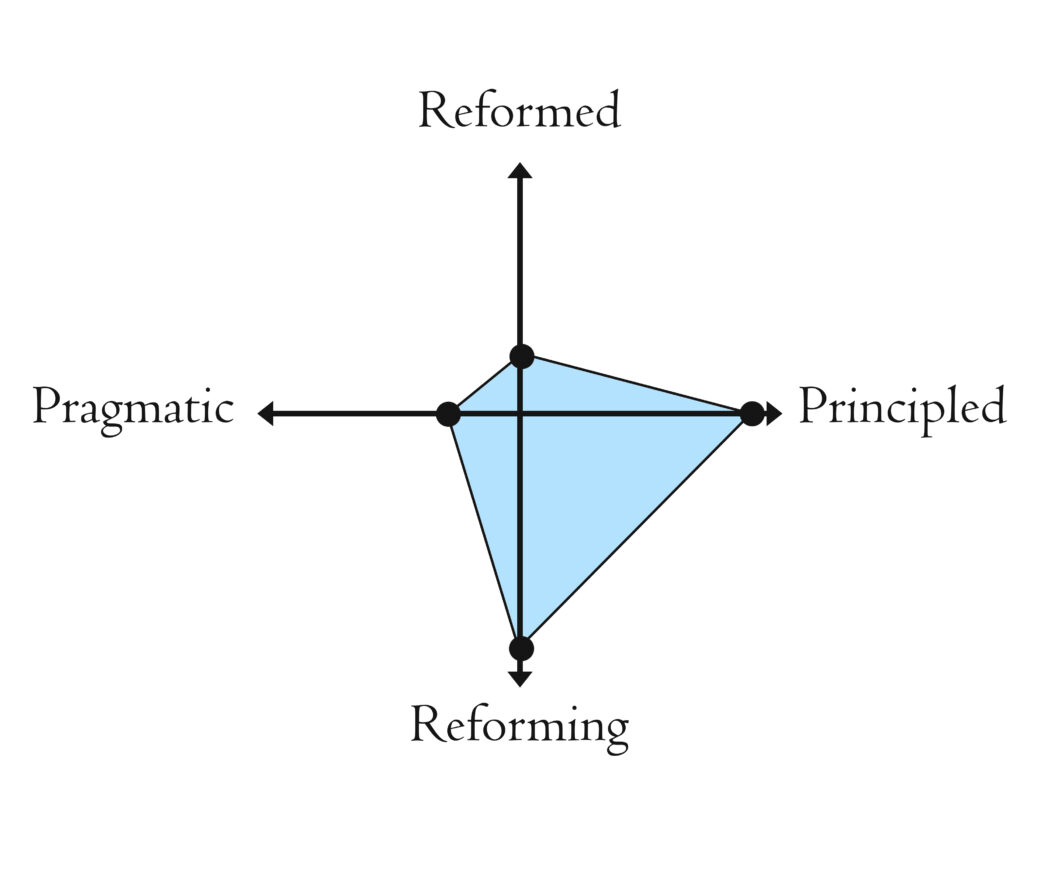

I became a little uncomfortable particularly through the introduction of this axis with the way each axis was reduced to a sort of binary in order to produce a single ‘plot point’. This is also true of the X and Y axes.

Reach Australia and its supporters would, of course, rightly claim that they are not disinterested in personal spiritual health; the difference is not binary but rather a matter of strength of conviction and emphasis. Most Healthy Churches folk are also thinking about things like buildings, and using technology and techniques for the day to day operation of their communities (though they may sometimes ask questions about the impacts of these technologies and techniques that others don’t). The people who gravitate to the fullest extremity of either pole on this axis become sort of caricatures (like Mark Driscoll maybe).

I started to wonder if a blob graph of sorts — or a Spider graph — would be a better representation of our ability to hold things in tension.

If I was simply graphing myself in this way on the initial two axis graph I’d look a little like this.

It’s harder to do a ‘blob’ on a 3D graph so I decided to flatten it, and as I did, I reflected a little more on my own experiences in church leadership and began to see correlations between different points on the existing axes (I reckon if you just picked the pole you emphasise you’d find ways that points interact that are similar to, for example, the way Intuition and Feeling intersect in the Myers Briggs schema).

Presbyterianism, classically, operates in a sort of polity or leadership tension somewhere between the top down ‘episcopal’ nature of Anglicanism, and the bottom up ‘congregational’ nature of the Baptist movement. There is, however, an emerging leadership style — not simply produced by pragmatism; sometimes produced by theology — the ‘pastor as CEO’ model, where accountability structures — or even the congregation — are seen as impediments to pursuing a vision.

This vision could be around a massive megachurch movement or an introspective house church movement; it is not necessarily wedded to a particular model — though it does explain certain denominational models — so it deserves its own axis. So. I give you the Christian Spider Web (I was, I admit, a little inspired by playing FIFA).

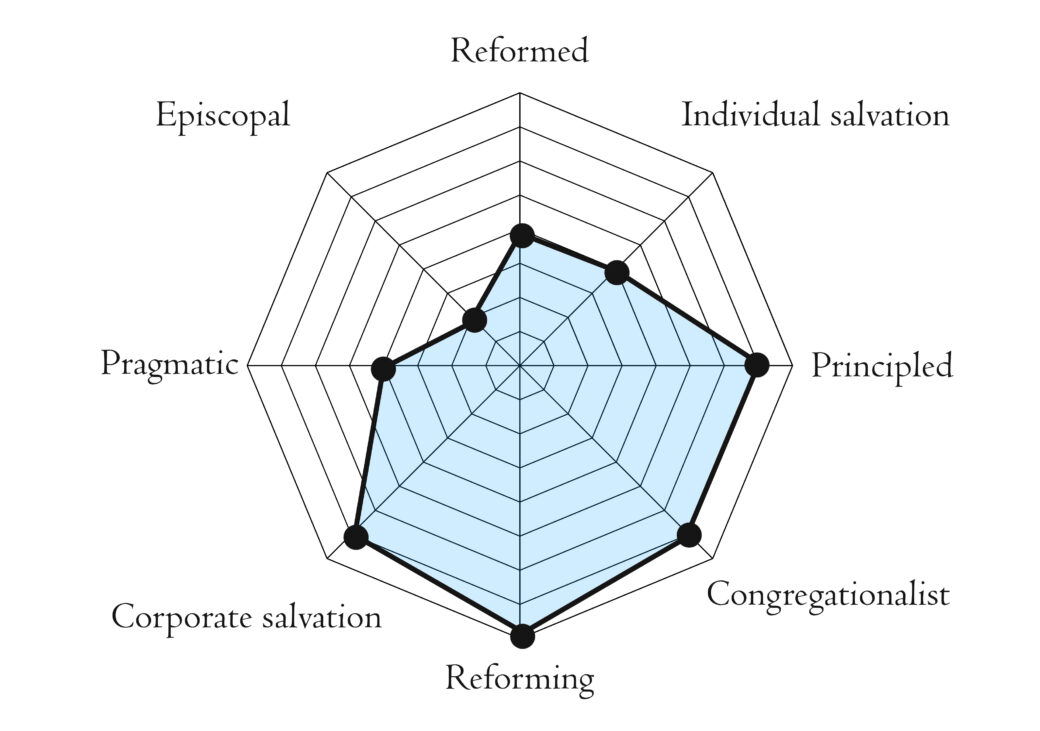

Here’s what it looks like when I plot myself on this model. I’ve found it helpful to both understand my own convictions and to be able to account for the overlapping similarities and differences I have with others. I’m not sure denominations can, or should, normalise a particular type (though some distinctives are features of different traditions).

There are other axis or poles one might add to this web; I had wondered about whether ‘pragmatic’ or ‘principled’ is the best descriptor or distinctive of those whose emphasise align with Reach Australia or Healthy Churches, or if the distinction is in, perhaps whether one reads the great commission as an instruction to make converts (through evangelism) or disciples (through transformation via worshipful obedience to the commands of Jesus) — or even whether one is extroverted and the other introverted (or introspective). Both of these could replace pragmatic/principled or be their own pole, though I think they intersect in interesting ways around the current principled/pragmatic line. I suspect, too, that those who emphasise Healthy Churches would have a view of evangelism that sees it best produced in and through a healthy alternative plausibility structure following the ways of Jesus, not the ways of the world, much as the pragmatic folks would see obedience to Jesus expressed in evangelism (and participation in the life of the church community or event) — though there’s a sense, on this axis, that what you win them with you win them to, and it’s not necessarily that people hold a tension or move from left to right. In many cases in this schema there’s a ‘both/and’ but the tension is resolved differently by different people with the end result being church communities that look and feel substantially different.

Anyway. Would love to know your thoughts on whether this sort of tool is useful for thinking about yourself, or your relationship with others within the church.

Comments

Good stuff. Thoughtful and thought provoking.

I am in a very similar place to you, with possible exception on the Episcopal/congregational axis. I am uncommitted on that. I see advantages and disadvantages in all kinds of church governance and various elements of biblicalness. I don’t think any system I have seen can legitimately claim to be biblical- certainly not the Presbyterians, who seem to claim that with more fervour than anyone else I know.

Thanks Nathan, that was a really interesting read. I’ve never been involved in Presbyterianism and probably won’t be in the future, but I can see that the same general approach would work in both the Anglican Church I was involved in most recently and some of the churches I was involved in before that. In the Anglican church there would be a line for liturgical vs ‘simple’ or ‘informal’ in worship, one for traditional vs modernising thinking mainly about church structure and governance, something like evangelical vs progressive or however you would put that, and an axis around justice vs individual spirituality. I’m trying to think how it would apply to the Brethren where I went in my 20s…

Helpful and interesting stuff. One issue this raised for me was in relation to “Reformed/Reforming” axis.

“Reformed” generally refers to those who adhere to the theological tradition which emerged (?) at the time of the Reformation. It was a reformation AWAY from Roman Catholicism TO a more biblically-faithful reading of the Bible and the resultant ordering of ecclesial life. The “Reformed” tradition has been able to trace its early movement AWAY from something, TO something else.

But I’m curious about those who might regard themselves as “Reforming”. What exactly are they moving AWAY from, and what are they moving TO? And why?

I personally think (as do others) that we should be both Reformed and Reforming. Of course that sounds great until someone tries to actually do the ‘Reforming’ bit.

Hi Matt,

I guess I’m happy for people to be both ‘Reformed and Reforming’ — and that would describe those who simultaneously sit somewhere in favour of the ‘resultant order of ecclesial life’ produced in the Reformation, while recognising that, say, Biblical studies continued developing after the Reformation so that we might bring different readings to key passages that shaped certain convictions in the WCF; whether that’s on, for eg, worship, or politics (or a variety of other things — like, for example, I’d take a different reading on Romans 7 to the WCF).

So I’d say the Reforming who aren’t holding the two axis in tension are those committed to the ‘church always reforming’ in the light of Scripture, rather than simply those who draw a line in the sand 500 years ago (or approx 480 if we’re talking WCF). Experientially I’d say the Reforming are those committed to the sort of Biblical Theology produced by Goldsworthy and at Moore College (or under its influence), probably developing a bit from Knox and Robinson as well (as well as subsequent thinkers); rather than a sort of expressly ‘Covenantal Theology’ (how many Covenants are there is another point I suspect many depart from the WCF…); these might be those who signed up with the Presbyterians as a “good boat to fish from’ for evangelical ministry with a Biblical Theology flavour (Sydney Anglicans outside of Sydney, who lean heavily into the Declaratory Statement; I’d observe that there are some at GAA and in online Presbyterian groups who would prefer we ditch the Declaratory Statement because it waters down the Confession).