This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 46 minutes.

Well, we’re at the end of the beginning of the beginning. Like any good origin story, the scene is set here for the rest of the franchise. Modern origin stories — like in the Marvel universe — give us a picture of what heroism looks like, but also, if they’re any good, they give us a sense of the setting, not only of the external threat — the baddy — but also the flaws of the heroes that are going to be part of their story.

So, let’s just use this lens on Genesis for a moment as a way of recapping where we’ve been. First up, there’s the question ‘who is the hero’? One of the mistakes we can make with any part of the Bible is jumping to seeing humans as the hero, or even the subject of the story. Genesis tells us straight up that this is God’s story, not only as the author but as the one who’s acting to create, and we get the setting here too, not just the ground but the heavens and the earth (Genesis 1:1).

We saw how there’s a hint that maybe heroism would look like bringing heaven and earth together, but for humans, it’ll look like joining God, filling the desolate and uninhabited earth (Genesis 1:2) with life that reflects his rule, his kingdom, as his image-bearing representatives, like the sons of God were meant to reflect his rule in the heavens (Genesis 1:26).

We’re not the hero, though. We’re the kids dressing in costumes, or maybe we’re the Hawkeyes, the Black Widows — heroic people without heavenly power. We’re not Aragorn or Arwen. We’re the Hobbits, the ground-level heroes.

And we met our first big baddy, a heavenly critter of some sort who turns up as a legged serpent, a dragon even, who wants to craftily pull people away from defining heroism as reflecting who God is to defining heroism as being godlike on our own terms (Genesis 3:1, 5). This leads to grasping, and then quickly to violence (Genesis 4:8), building violent cities, where vengeance creates a vicious cycle (Genesis 4:17, 24), ultimately producing a world soaked in violence (Genesis 6:11).

We even met heavenly baddies who joined the cause of the big baddy like we’re meant to join the cause of God, grasping humans, “taking any they chose” (Genesis 6:2) like Adam and Eve plucked the fruit, creating super-powered baddies, the Nephilim, warrior kings of name (Genesis 6:4), who will pop up in the story of the Bible as giants or the leaders of violent empires.

And though we saw godliness as generative, as creating life and providing abundance and hospitality, and beauty and order and love, God, the hero of the story, detests this grasping violence, sin, our attempts to be godly, and so he de-creates and re-creates in the flood, exiling evil and violent people from his presence (Genesis 3:24, 4:16), and then his world (Genesis 6:13).

Exile is pictured as this movement east, away from the Garden. And in our last ‘episode’, we landed in the furthest east we get here, in Babylon (Genesis 11:2), where a warrior king, Nimrod, is trying to build a name for himself by building another city, Babylon (Genesis 11:4).

Each week we’ve traced how this origin story creates threads or scenes or patterns that repeat through the story where our picture of God and heroism develops, but mostly it develops against the struggle, the failure, for the humans in the story to be heroic, to be godly, and how much we’re trapped in the coils of the serpent.

But in the midst of the story, we’ve been tracing two lines of seed set up in Genesis 3 (Genesis 3:15). There have been two types of human, children of the serpent like Cain, Lamech, and Nimrod, and children reflecting the image of God, potential serpent crushers, new Adams — Abel, then Seth, then Noah.

And now, in this line of Shem, the line of name, that gets us to Abram (Genesis 11:10, 26), the camera narrows down again after the Babel story. We had a family tree of the three sons of Noah back in chapter 10, and now we get the family tree of the one son whose line we’re going to keep watching.

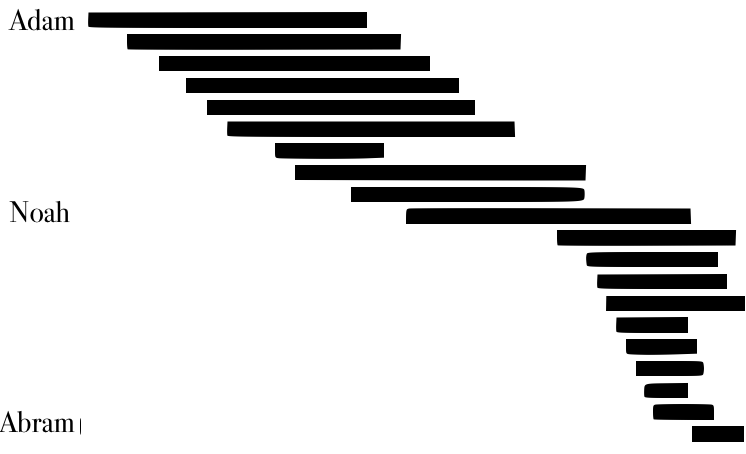

Now, there’s a thing we haven’t looked at much in these genealogies as we’ve passed them by, but Genesis keeps telling us how old someone is when they have a kid, and how old they are when they die, even if the camera moves on from that person. It follows this formula: When ____ had lived X years, he became the father of _____. After he became the father of ____, ____ lived X years and had other sons and daughters (Genesis 11:10-11, 12-13, 14-15, 16-17, 18-19, 20-21, 22-23, 24-35).

For this whole family tree, right up to two years before Abram is born, Noah is still alive. There are so many generations of this family tree still mingling around the traps, and so when Abram’s dad is called to uproot and leave, this is a big deal. He’s pulling out of a family system where multiple generations are still around. Here’s a visual of the overlapping lifespans of each person.

There’s a little more backstory to this repeat of the line of Shem. We met Peleg back in chapter 10, and his brother Joktan, but then the story divided (Genesis 10:25), we followed Joktan’s line. We’re told the world was divided when Peleg was around, so I reckon that’s giving us a bit of a timeline for when the Babel story happened, when Peleg’s great-great-grandfather’s brother’s grandson Nimrod was doing his thing.

All these characters are still very much related in an extended family network, and the scattering from Babel into nations with different languages is starting to unfold. And one way it unfolds is in this family line we zoom in on — the line of Peleg (Genesis 11:18-19); Shem’s other great-great-grandson, who turns out to be the great-great-grandfather of Abram, and the camera has zoomed all the way from an account of the heavens and earth (Genesis 2:4), to the account of Abram’s dad Terah (Genesis 11:26-27).

We’re told a couple of times his roots are in this place called Ur of the Chaldeans (Genesis 11:27-28). It’s the land where Abram and his brothers are born, and one of Abram’s brothers, Lot’s dad Haran, even dies there. Now, this is significant because Ur of the Chaldeans is in Babylon. The Chaldeans become part of Babylon. In fact, if you flick forward to Jeremiah, where Jeremiah tells the story of God using Babylon to bring judgment on Israel, through Nebuchadnezzar, where it says Jerusalem was surrounded by Babylon and the Babylonians, it’s the same Hebrew word here for “Babylonians” that we get for Chaldea in Genesis (Genesis 21:4).

Abram’s family, the line of fruitful seed we’re going to follow for the rest of the story, all the way to Jesus, was born in Babylon and comes out of Babylon to become God’s chosen people. They start off with Abram’s dad Terah taking his brother, his nephew Lot, and Abram, and Abram’s wife Sarai, out of Babylon towards Canaan. They start heading west, which is a significant movement. Remember back to the idea that the gates of Eden are on the east, so to head west is to head back towards Eden. And Canaan is significant too because it’s what’s going to become the Promised Land, the land flowing with milk and honey. It’ll become Israel, where the temple mountain is and where God dwells with his people.

But they don’t make it. They stop in Harran (Genesis 11:31). Now, there’s some fun Hebrew visual punning going on here with the name of this place Harran, and the name of Abram’s brother Haran. By changing just one consonant slightly, you get two different names with two different meanings. But I wonder how much both are being invoked. Haran, Abram’s brother, his name is the Hebrew word for mountain climber. It gets used six times in five verses here, while Harran, the city name, is a word that means crossroads, a word borrowed from the early Babylonian empire, which named the city, and on the map, this city lands in Assyria, where Nimrod also built cities. Terah and his family of mountain climbers reach a crossroads at the edge of the empire set up by Nimrod, and they stop. They’re right at the edge of the east.

They’re at a crossroads. Do they leave the land of the east, where their family is connected, or do they go west, towards Eden, or in this case, Canaan? And Terah and his son settle there. Terah dies there, at the crossroads (Genesis 11:32).

So from this crossroads, God calls his people, his line of faithful seed, from the line of Shem, name, and the line of Eber, the Hebrews, who he’s going to attach his name to, out of the land of Nimrod, and Babylon, and its walled cities, into the land. He calls Abram to leave his established family network, the people and household that give him security, and go into a land God will show him, to keep going west (Genesis 12:1). God makes these promises that are going to set up the story of the rest of the Bible, all the way to Jesus.

God promises Abram’s family will become a great nation. They will be blessed, like humans were blessed in Genesis 1. They will be fruitful and increase in number, and they’ll do this in relationship with God. They’ll be an image-bearing people so that God will make their name great, and they’ll be a blessing to others. In fact, whether or not people are blessed like humans in Eden, or cursed, like humans east of Eden, is going to depend on how people treat this line of seed, starting with Abram. And through this line, all the nations we’ve just seen spread through the earth will be blessed (Genesis 12:2-3).

Now, there are some barriers here that pop up in the narrative. For starters, we were already told Sarai couldn’t have kids (Genesis 11:30), and things get pretty sketchy pretty quick in terms of how Abram and Sarai deal with this promise. The first thing Abram does is demonstrate faith at the crossroads. He and his family, and Lot, who throws his lot in with Abram, they pack up, and they head off to Canaan, and arrive there (Genesis 12:4-5).

Where Terah was heading, and where God told him to go. He goes to a great tree, where God appears to him. There’s an Eden image here (Genesis 12:6-7). God promises this land to Abram’s seed, his offspring, so Abram and his family stake a claim. Abram does what Noah did after the flood, and what faithful people will do through the story all the way through. He builds an altar to the Lord. He’s a new Adam, a human who is in relationship with God.

He moves further west, towards Bethel, a place named house of God. That’s what Bethel means, not towards a hill. This is the Hebrew word for mountain, where he puts up a tent and builds an altar, to the east of Bethel. So the house of the Lord, framed like a new Eden, is to the west, and he calls on the name of God (Genesis 12:8-9).

A tent. An altar. Calling on the name of God. Near the house of the Lord. This is tabernacle type stuff. This is a high point. It sets up a sort of ideal, and then, things, like they often do, go downhill as Abram heads into Egypt because of a famine, which is a scene that’ll repeat with his great-grandkids (Genesis 12:10).

There he creates a repeat of the fall. There’s a repeat of seeing beauty and taking, only this time Abram gives Sarai to the Pharaoh. It’s bad (Genesis 12:14-15). God sends plagues on Egypt. We’ll see that again. It’s a curse on the Egyptians, those who curse Abram are cursed (Genesis 12:17). And the Pharaoh sends him out of Egypt and back to Canaan. It’s a mini-Exodus (Genesis 12:19-20).

In the space of one chapter, Abram leaves Babylon and becomes a new Adam, promised the land of Canaan, and then leaves Egypt with the wealth of Egypt given to him as God blesses him and curses the people who curse him. But right in the middle, we see Abram as this conflicted character, a new Adam who God’s going to work with, who calls on God’s name, and a reflection of the old Adam, who brings curse as he rules over his wife, and lets her be taken.

What a scrambled mess. But what a picture of the scrambled mess that this line of seed goes through in the Old Testament as they end up in Egypt, and are created through an Exodus, coming out of Egypt, and into Canaan, setting up an altar on a mountain, not just in a tent, but in a temple, a house of God.

In chapter 13, when he comes out of Egypt, Abram and Lot are both blessed with wealth, and rather than fighting, Abram lets Lot choose what land he’s going to settle on. Lot land that is described as being like Eden, and he heads east again, while Abram chooses the land on the west, the land of Canaan (Genesis 13:10-12).

Finally, Abram goes to live near some more trees, where he pitches his tents and builds an altar (Genesis 13:18). There’s an interesting contrast set up between Nimrod and Abram, where Nimrod builds a city with bricks and Abram sets up as a nomad, living in tents in the trees. It’s a real return to Eden.

And so in Abram’s story, we have a pattern that defines Israel’s story and Israel’s hope, even as they come out of exile in Babylon, and head back west into these same places. Going back to the call of Abram out of Babylon, to enter a covenant with God for the land. And Israel coming out of their suffering in Egypt, to make a name for God (Nehemiah 9:7-10). Only the retelling of this story doesn’t end in hope in Nehemiah, but in despair. Even as the people rebuild the temple and the walls in Jerusalem, they know exile isn’t over yet.

They’re in the land, but now they’re in the land and still in Babylon; they’re slaves still ruled by Nimrod-like kings because they keep doing evil (Nehemiah 9:36-37). They’re in distress — because of their sin. Their harvest is going to foreign Nimrod-like kings — all the Eden-like fruit goes elsewhere — and they want delivery.

They’re left wondering how the promises to Abram are still being fulfilled. What home looks like. Whether they’ll ever be a house of the Lord; a people who meet with God and so provide blessing to the nations ever again.

They want the hope expressed in the prophets to actually be fulfilled; for God’s people to be called back from the ends of the earth, for God to keep His promises to Abram to bless the world through his servant — this line of seed. They want to know that even in exile, God hasn’t rejected them and will call them back to produce blessing and fruitful life (Isaiah 41:8-9).

They want to truly come out of Babylon; led by a new Adam, by a new Abram, a son of Abram, to be led by a king. They want exile to be over. And Genesis sets us — children of the nations — to want that for us too; restoration from our own exile, the exile from Eden and at Babel into these cities of the world, ruled by these powers and the human rulers who line up with the snake.

So let’s tie these threads together — and maybe the threads of the whole origin story as we’ve seen it. We’ve seen a few times that the end of the story — Revelation — is a new beginning, shaped by the origin story in Genesis. It gives us not just a first story to live by but shows how the gospel becomes our origin story and what the end of the story we’re living towards looks like.

It has the same hero — God — but revealed in a more pointed way in his Son, the victorious King, who appears from Revelation 1 to the end as the Son of Man and Son of God who rules in a way that truly reflects God (Revelation 1:5). John is writing to the church, communities of Jews and Gentiles around the world facing the beastly Babylonian rule of Rome, but he calls Jesus the ruler of the kings of the earth. He says he’s freed us from sin by his blood; ending the claim the powers and principalities had over Israel in Nehemiah, and over all of us from Genesis, and making us a kingdom of priests to serve God (Revelation 1:6). This is what Israel’s called in the Exodus, as they’re called out of the nations, and it’s what we’re called to do as Jesus calls us out of these cities ruled by these kings to live under his rule. He’s come to deal with rebellion in the heavens and the earth — and the same big bad guy, the dragon, Satan (Revelation 12:7-9), and his heavenly and earthly minions — beastly powers and principalities and their human expressions — Nimrod-like cities of Babylon (Revelation 13:4).

And it tells the story that the hero wins. He destroys the beastly and his buddies — the kings of the world, and their armies — the Nimrods in fiery judgment — and the dragon, who he destroys, with the beast, in fiery judgment. He’s the snake crusher (Revelation 19:19-20, 20:10).

Revelation tells this new exodus story, where God’s king calls his people out of Babylon; Babylon and Egypt and Rome and Jerusalem and whatever cities we belong to that teach us that violent grasping is how we secure the good life. Our economies built on grabbing wealth and beauty on our own terms — where we chase Eden life without God — and making a name for ourselves.

It describes this judgment on Babylon, on the cities of Nimrod that started in opposition to God in Genesis; Babylon the great is falling because it has become a dwelling place for demons and impure spirits — for those like the Nephilim, opposed to God (Revelation 18:2). These are the cities of those nations disinherited at Babel and given to these powers, who refuse to come home.

Babylon becomes a symbol of political and economic rebellion against God: wealth, power, an empire opposed to God that corrupts the nations drunk on the lies of the serpent and kingdoms built on grasping (Revelation 18:3-4).

The world that rejects God’s faithful seed faces curse — these Babylons will get something like the plagues that hit Egypt when Abram was there, and when Israel left in the Exodus — something like the flood, because her sins are piled up like bricks in Babel. Revelation describes judgment falling on all the beastly kingdoms represented by Babylon — Rome, Jerusalem, our own human empires — as a result of the death, resurrection, and rule of Jesus.

But God calls us to be like Abram — to come out — leave these empires and find Eden-like life with God, with the fulfillment of the same promises driving us — blessing, a home, and being his nation of priests (Revelation 18:4-5). And we’re invited to hear God’s call to Abram to come out — to live as an exodus people — not a people exiled from God, but people like Abram who know our home is the new Eden — because we’re following a king who brings blessing to those who receive him, and judgment — curse to those who don’t.

Babylon is coming down to earth. Falling. And blessing is going to be found with God’s faithful seed, who’ll bring a heavenly city — a heavenly city brought down from the heavens to earth — an anti-Babel that achieves all the Sons of God and the Nimrods and the Nebuchadnezzars were trying to do; and is a more permanent home than Abram’s life under the Eden-like trees (Revelation 21:1-2).

A new Eden with a new tree of life (Revelation 22:1-2).

The end of the story ties all these threads together, and it invites us to live with this as our story — our hope.

So now we find life under the branches of the tree that gives life — the cross — while we wait for this new tree of life.

We find life with Jesus as the one who connects us to life with God as we feed on him — called to come out of Babylon and come to him (Revelation 22:17).

Abram’s story becomes our story — we all come to a crossroads in life where we have to decide whether to choose Babylon, and the serpent-rulers, or to head towards life up the mountain and into the heavens with God — and for us the crossroads is the cross — where Jesus secures the fate of the serpent, and the earthly kingdoms opposed to him secure their fate too.

Communion, or the Lord’s Supper, is such a great picture of this shift. It’s easy for us to ask what does this mean for us, to not live in Babylon even if we reside there. This means — like Israel in literal Babylon — not seeing Babylon as home, and believing its stories about God, the world, and the good life. That’s what these texts did as a story for Israel.

Communion with God doesn’t mean leaving our cities — it actually means living in them, but living differently.

A bit like Israel when they were in exile in Babylon who weren’t, at that point, called to pack up everything and get out like Abram; but to plant their own trees; their own Edens in the city that wanted to be just like Eden but without Israel’s God in the mix; they were to do this and love their neighbors as they lived a better story; seeking the peace and welfare of the violent city (Revelation 18:4-5).

Precisely because they knew God was going to call them out and to a new home, and this was how to testify to that hope; to God’s promise to bring them back in a new exodus (Jeremiah 29:10-11).

The catch is we’re not Israel in exile, or even Israel restored — we’re citizens from the nations, also brought back — not exiles, but those who’re on the journey home to God even as we live in empires that will fall.

The trick is to make homes — to be dwelling places of God in the world, but not to be too at home. To do the Abram and sit under Eden-like trees — not as exiles cut off from God, but as people who know we have a home that we’re waiting for, so that we’re never truly at home in the places we live; we’re foreigners.

There’s an early letter circulated in the Roman empire in the 2nd century, the Epistle to Diognetus, about how Christians lived in this tension. Where they might speak and dress the same as their neighbors. But had a “wonderful and confessedly striking method of life,” dwelling in their countries as sojourners — knowing this isn’t the end of the story because we have a home.

This letter unpacks how Christians lived differently — because we have a different story about what it means to be human. This played out in how Christians shaped their homes — their families and their tables — and how they approached sex. They were marked by generosity — by participating in a different economy. They lived lives on Earth as citizens of Heaven.

Living this better story means not participating in the religious worship of the cities we find ourselves in — which was easier when there were literal temples to sex, and money, and success in the landscape of a city. We’re still worshippers; and we still have our own versions of temples and rituals and sacrifice we make; and we still live in empires built on the capacity to do violence and the desire to constantly grasp our share of capital, as nations and individuals. And we’re called to come out and live differently.

There’s an interesting picture of this in Corinthians — and this’ll lead us into sharing communion together — so can I invite those who’re handing out the bread and juice to come forward, now, and as they do, if you’re someone who’s heard the call out of Babylon, and into life with God — even if you want to take that step today — just grab hold of the bread and the juice and consider what that represents.

In Corinth, Paul talks about the cup of demons (1 Corinthians 10:21). He calls the church not to participate in both the Lord’s cup — being united with Jesus, and this cup of demons. Now, this is almost certainly partly about idol temples, where parties happened at altars, but Corinth was also home to an imperial cult temple; a temple to the deified Caesars — at the highest point of the city. The Roman rulers learned a bunch from Nebuchadnezzar — and the way they talked about the spirit of the emperors who became gods. The thing that made him a god — was his daemonius — his demon.

There’s this inscription about Nero taking the throne that uses this word demon to describe his spirit; his genius:

“…the expectation and hope of the world has been declared emperor, the good genius of the world and the source of all good things, Nero has been declared Caesar” (P. Oxy. 7).

An early Christian, Tertullian, points out that Christians don’t swear to the demon of emperors. Demons are for exorcising:

“We make our oaths, too, not by ‘the genius of the Caesar’ but by his health, which is more august than any genius. Do you not know that genius is a name for daemon? Daemons or geniuses, we are accustomed to exorcise, in order to drive them out of men…” (Tertullian, Ad Nationes, Chapter 17).

To share in the table of the empire was to call Caesar lord, and commit yourself to his rule; and Revelation certainly has Rome in view as a beastly human kingdom. The Corinthians were called to live in the city of Corinth, but under the rule of Jesus — in communion with him — not giving their lives to the earthly kingdoms of people who claimed to be like God and went about doing that through grasping and dominating.

Sharing in the cup of Jesus — at his table — means not being shaped by the violent and grasping patterns of people who believe the origin stories that say ‘this life is all there is’ and we’re just a speck in time and space produced by randomness so we should grab what we can, while we can, or look to make life as long as we can by seizing godlike control of ourselves. And so, we serve the God-king who comes to bring heaven to earth the way Adam was meant to — not by grasping, or becoming beastly, but by giving — and that becomes our pattern; a pattern that’ll produce fruit in our lives as his Spirit dwells in us, and as we tell ourselves his story in our own Babylon, and here is a call to come out.

Will you take and eat this bread remembering the body of Jesus, given for you, that you might live in communion with God; his heavenly life dwelling in you so that your home is this heavenly city, the new Eden?

And will you drink this cup — remembering that you are not united to Satan or demons or the powers and principalities that make Babylon; that Jesus drank the judgment poured out on those empires for you on the cross, so you might drink from his cup and share life with him under the trees of the new Eden, by living waters.