This is an adaptation of the fifth talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, or watch it on video. It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

I’m going to open this piece with a content warning — we are talking about sex, and mostly in a “heteronormative” way; not at the expense of acknowledging LGBTIQA+ desires and attractions. In fact, I hope to acknowledge these desires and experiences as real and important, while providing an account of the Bible’s view of sex and marriage. I recognise that this will be hard for many of us to sit with, for a whole bunch of reasons — but sex is an unavoidable part of being human; it is our personal origin story (as in, you had parents), and it is part of navigating life in the modern world, whether you are having sex or not — or wanting to, or not.

I am going to kick off this week with a recap of where we have been as we hit the halfway point in this series. We started out asking why the modern Western world seems to be fragmenting us, leaving us overwhelmed while robbing us of a common narrative.

We have seen — following Charles Taylor — how part of that loss involves a shift from life in an enchanted cosmos to a disenchanted universe, and this has left us not as people open to outside forces, like God, but as “buffered selves”: liberated individuals who are finding freedom and identity in expressing our inner self authentically, often using the technology we create to overcome, or even escape, the limits of our bodies.

I know that has been overwhelming — and long — and a lot to take in. But so is modern life — and we need to try to work out what is going on, and how we should live, if we are going to be humans who live lives integrated with God’s design for our humanity.

One of the challenges we face with the loss of one big story is that we are now often living in multiple stories at once, that often compete. We have often incorporated stories about being human into our lives as Christians. So where last week we looked at a desire to escape our bodies using wires, this week we are going to look at how our bodies are wired for desire.

There has been a subtle shaping to our themes. Week by week across the term we are following the shape of our humanity that we find in the story of the Bible, starting with our origin story.

We have moved from the Triune God as creator (Genesis 1:1), to what it means to be made in his image — as individuals and in community (Genesis 1:27), to how we exercise dominion over the world through our creating — our technology (Genesis 1:28), to how we are given bodies, and souls, and the limits of life in time and space as gifts from God (Genesis 2:7–8).

We are working our way through Genesis 1 and 2 — asking what we are made to do — then seeing how sin and curse deform the image we represent, and how Jesus redeems and restores us, and what it looks like to have our future shape life as humans in our present.

Which means, as we step through Genesis — today we are talking about desire and sex:

We are people with bodies equipped with senses, geared towards sensual enjoyment of beautiful and delicious things made by God. Genesis tells us the trees in the garden were “pleasing to the eye” and “good for food” — both statements involve our senses (Genesis 2:9). Part of this picture of senses and goodness and embodied life involves intimacy with other humans — and even sex between humans — a man and wife — united as one flesh (Genesis 2:18, 24).

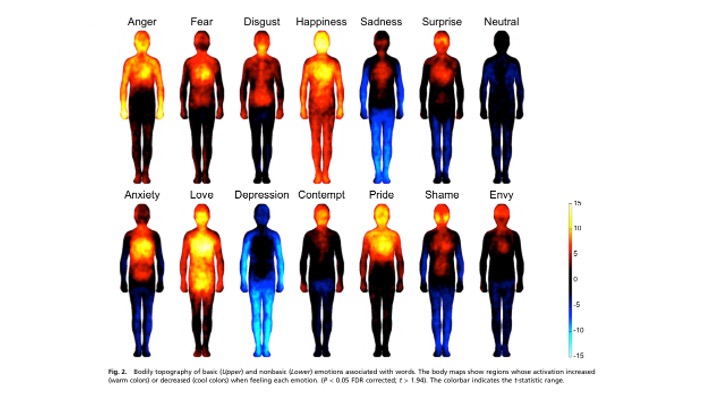

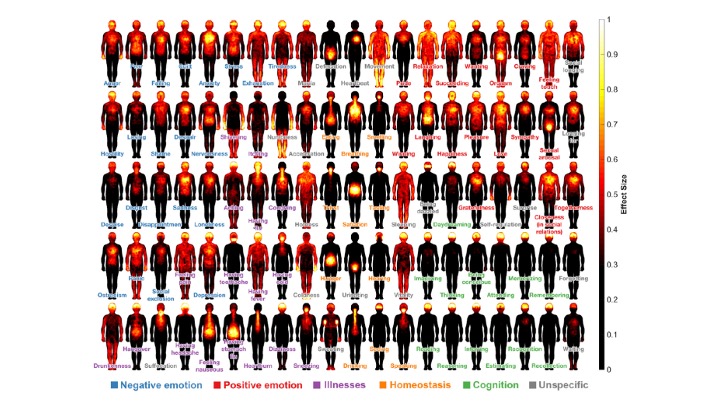

Our bodies and souls and minds are interconnected in profound ways. Desires are a place where they come together. Our emotions are not just things we think or feel in our brains — they are experienced all over our bodies. You can map desires and emotions on your body using heat maps — and even more:

Feelings and movements light up our bodies the same way; our pleasures and pains feed back into our desires.

The push away from the body is made even stranger when we consider how we learn our desires through our bodies.

In the modern world, where we have replaced God, one of the most natural things to replace God with is our desires. We have created a new social imaginary — a new way to understand being human that makes it impossible to imagine a good life without our bodily desires being fulfilled. Thanks to cultural and technological changes like the pill, and increasingly visual media technology, sexual desires have become one of the primary expressions of sensuality and desire.

This has created a phenomenon asexual author Angela Chen describes as “compulsory sexuality,” where sex becomes a necessary human experience. If you think it is hard to navigate life in the modern world, imagine navigating it as an asexual person — that is the “A” in LGBTIQA+. Asexuals do not experience sexual attraction, and so live in a world built on desires that are foreign to their experience.

Chen says the myth that we have to be sexual to be human is built on two parts — first, a society saturated with sexual imagery:

“The sex myth, which is an extension of compulsory sexuality, has two parts. One is obvious: sex is everywhere and we are saturated in it, from song lyrics to television shows to close-ups of women’s lipsticked mouths eating burgers, meat juice trickling down their throats.”

Angela Chen, Ace: What Asexuality Reveals About Desire, Society, and the Meaning of Sex

And second, the idea that sexual pleasure and sexual desires are ultimate:

“The second part is the belief that ‘sex [is] more special, more significant, a source of greater thrills and more perfect pleasure than any other activity humans engage in.’ No sex means no pleasure, or no ability to enjoy pleasure.”

Angela Chen

It does not take much to jump from that to a view that being who you are sexually — embracing and expressing your desires — is the key to being truly human.

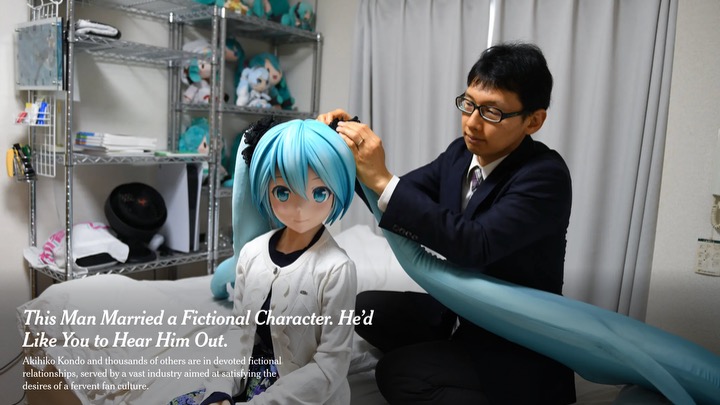

This goes in some increasingly strange places for people who cannot get that desire fulfilled and end up turning to technology.

There is a growing trend where people marry fictional characters and engage with them virtually; and one futurist predicts that within the next twenty years robots are going to be the answer to our sexual desires — maybe even for most people:

“There are millions of people out there who, for various reasons, don’t have anyone to love or anyone who loves them. And for these people, I think robots are going to be the answer.”

David Levy, Love and Sex with Robots

There is a whole industry devoted to developing that technology. And of course there is porn and electronic images — that we will consider more next week.

We find it hard to believe that a person can flourish without expressing our sexual desires, or at least articulating them as core to our personhood. This has produced more complexity — creating an environment where our attempts to articulate our desires and identity involve an ever-expanding vocabulary.

And maybe you are here — and you are over fifty — and even though you have lived through or after the sexual revolution, you are thinking “this is all too much; there are new labels all the time.” I want to suggest this new world is confusing for everyone, which is why there is an ongoing evolution of language and behaviours as people express themselves.

You might be at the point in your life where you also reckon all this stuff about sex is for young people, or for married people, but I want to suggest sex is an embodied desire that Paul uses to talk about how we use our bodies; and you still have bodies — and the role you play in a church community and in your families means it is worth trying to understand what is going on as you guide younger folks in how to steward our bodies and cultivate godly desires.

Like any idolatrous social imaginary, this is damaging — not least because this mythology we live by is typically built around male sexual desire. In a satisfaction-at-all-costs world where “nothing is sacred” about our bodies except autonomy and consent, this has produced what has been called “porn culture,” which is destructive for women — for everyone really — where we are taught women’s bodies exist to satisfy men.

One Christian response to the shifting modern world has been to assume that sexuality is fundamental to our humanity, and to build what has been called “purity culture.” Katelyn Beaty wrote about this for The New York Times in a piece titled ‘How Should Christians Have Sex‘. Purity culture includes the idea that marriage is where desire is satisfied, but particularly that a wife’s job is basically to manage her husband’s uncontrollable urges. As an unmarried woman she has found purity culture dehumanising. She says:

“Rather than emphasize the gift of sex within marriage, purity culture typically led with the shame of having sex outside of it… Young women, who were expected to manage men’s lust as well as their own, fared the worst.”

Katelyn Beaty, New York Times, ‘How Should Christians Have Sex’

But at the same time, she wants to recognise that our bodies are not nothing; and that sex actually involves the coming together of bodies and souls:

“So when a person engages another person sexually, Christians would say, it’s not ‘just’ bodies enacting natural evolutionary urges but also an encounter with another soul. To reassert this truth feels embarrassingly retrograde and precious by today’s standards… I yearn for guidance on how to integrate faith and sexuality in ways that honour more than my own desires in a given moment.”

Beaty

She is after a way to integrate her faith and sexuality in ways that move beyond her desires in any given moment — and that offer more than simply consent and “anything goes” as a way forward. And maybe that is you.

Katherine Angel is an author who has tried to explore a secular way beyond a sexual ethic just based on consent — and consent is important. In her book Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again she argues the issues leaving us cold and unsatisfied are built on inequality in how sex happens in our society, where women have been robbed of agency, and where the focus is on male gratification at all costs:

“Bad sex emerges from gender norms in which women cannot be equal agents of sexual pursuit, and in which men are entitled to gratification at all costs.”

Katherine Angel, Tomorrow Sex Will Be Good Again

She argues none of us is actually that good at articulating our desires in order to consent to what we want; and that we explore our desires and find fulfilment where there is openness and vulnerability in our pursuit of intimacy and mutuality, because we come to understand our desires as we use our bodies with that sort of connection. This is hard to do for buffered selves:

“The rhetoric of consent too often implies that desire is something that lies in wait, fully formed within us, ready for us to extract. Yet our desires emerge in interaction; we don’t always know what we want; sometimes we discover things we didn’t know we wanted; sometimes we discover what we want only in the doing.”

Angel

I think she is right — not just about sex — but about the way our desires intersect with our humanity and our relationships.

Two thinkers are particularly helpful here. The first is James K. A. Smith, who pushes the idea that we are lovers; that ultimately, we are what we love:

“To be human is to have a heart. You can’t not love. So the question isn’t whether you will love something as ultimate; the question is what you will love as ultimate. And you are what you love.”

James K.A Smith, You Are What You Love

We are not “brains on sticks,” or just meat sacks; we are pulled through the world by our love — our desire — and we cultivate our desires through bodily practices:

“We are not conscious minds or souls ‘housed’ in meaty containers; we are selves who are our bodies; thus the training of desire requires bodily practices…”

Smith

He reframes the idea of eros — one of the Greek words for love, where we get “erotic” — which he argues has been given a bad name in a pornified world:

“Human beings are fundamentally erotic creatures. Unfortunately — and for understandable reasons — the word ‘erotic’ carries a lot of negative connotations in our pornographied culture… In its truest sense, eros signals a desire and attraction that is a good feature of our creaturehood.”

Smith

This has left us ill-equipped to see how our erotic natures — our sensuality — are part of our creatureliness; our bodies. There is a natural response to beauty that is God-given and meant to be God-directed — it is just corrupted by sin.

Sarah Coakley — an Anglican priest and theologian — argues we live in a world shaped by Freud’s beliefs about fulfilling sexual desires being the basic urge at the heart of our humanity, with his idea that God is a projection. She says we have to flip that: it is desire for God that is our most basic need, and we have tried to fulfil that erotic desire with sex and idolatry, but these desires are a clue that tugs at the heart to remind our souls of our need for God:

“It is not that physical ‘sex’ is basic and ‘God’ ephemeral; rather, it is God who is basic, and ‘desire’ the precious clue that ever tugs at the heart, reminding the human soul — however dimly — of its created source.”

Sarah Coakley, God, Sexuality and the Self: An Essay on the Trinity

So here is the working idea for this week: we are made — male and female — in the image of the God who is love; the Triune God is an ecstatic communion of life and love that generates love that overflows into creation. Our desires are not just sexual, but sensual, and our desires are meant to direct us to God.

The way it is “not good” for Adam to be alone (Genesis 2:18) is because this image-bearing is impossible, not because he is a sexual man and needs an outlet, but because we are made as embodied people for intimacy and love who image God by loving in ways that generate life and love — and even more image-bearers. The way Eve is made from his side in order that they might become one is a description of our orientation to love; to unite ourselves in love in ways that generate love, and that can generate life (Genesis 2:22, 24). This was meant to happen in relationship with God. I am not saying that the only way to be human is to have sex and create children; but I am saying that being human means being designed to love in communion with God and others, and that one way such love is expressed is in sex and love in a one-flesh relationship as husband and wife.

This oneness is not just expressed in marriage. Paul is clear it is also expressed in the church, as the body of Jesus. But sin means our desires misfire. We have lost a way of being human because our sin has turned our hearts and desires in on ourselves, so we pursue self-gratification rather than self-giving in our relationships, with our bodies in the driving seat.

Jesus talks about our desires and our hearts when he talks about storing up treasures in heaven (Matthew 6:20–21), and what or who we serve being a matter of our love and devotion. He says we can only really serve one God; one master (Matthew 6:24), which is tricky in a world that has idolised sex and money and made us masters of our own lives. This idea is going to shape how we think about sex and sexuality and the way we fulfil those desires as humans, but also how “treasuring heaven” might play out in not having sex — turning that desire upwards.

Jesus lived an embodied life perfectly shaped by his desire for the kingdom of heaven — and without sex. He talks about eunuchs — and this fruitful way of being fruitfully human without sex or procreation (Matthew 19:12). He says some people are born this way; perhaps born without sexual desires — and there is a massive rabbit hole we could go down around the idea of asexuality that is part of the LGBTIQA acronym — and the way our eros-based society feels like it eradicates the possibility of people who just do not desire sex. Or perhaps he is talking about those who cannot engage in sex — as a result of trauma, or medical procedures, or the nature of their bodies — and if that is you, Jesus sees you, even if our world does not, or if it dehumanises you.

And there are those who are “made eunuchs” by others. In the ancient world eunuchs were people who had been castrated in order to serve royal households — not quite the nuclear royal family; they had key roles at the heart of a kingdom on the basis that they were not able to have sex.

There is an interesting thread where 2 Kings and Isaiah both prophesy that in exile, Babylon will make young Israelites into eunuchs — which, if fruitful life is tied to procreation or the satisfaction of sexual desire, is a pretty big deal (2 Kings 20:18; Isaiah 39:7). There is a good case to be made that Daniel and his friends — chosen as prime physical specimens and handed not to the chief official, but literally to the head of the eunuchs — would have been made eunuchs in order to serve in the king’s household the way they did (Daniel 1:3–4).

Jesus sees a place in the kingdom for those whose bodies have experienced these changes in a world that produces a way of life and a vision for the body different to God’s Edenic vision — whether because of the way a broken world is reflected in non-Edenic bodies, or the politics of the body, or idolatry, or medical treatment for cancer. This is not dismissing the way male and female bodies were created to come together, but we cannot elevate that vision at the expense of those who experience embodied life differently; or those who choose to live like eunuchs — without sex — for the sake of the kingdom of heaven.

This is such a profound passage for modern debates about our bodies, and I am not going to do it justice here. There are people in our community — both gay and straight — who, in order to use their bodies faithfully, are denying their erotic desires for other humans, while redirecting their hearts and bodies towards the kingdom of heaven; towards love for God, in ways that should teach us all about what it looks like to love God ultimately and be shaped by that love in a world built on the belief that sexual fulfilment is ultimate.

Finally, to 1 Corinthians 6. I think Paul has Jesus’ words in view when he writes about how we are to use our bodies and direct our sexual desires, because our bodies are temples of his Spirit and have been redeemed by God to be used for his glory (1 Corinthians 6:19–20). Paul applies this to how we approach sex and marriage, and he will go on to apply it to how we indulge our bodies in eating and in worship.

Paul picks up the Genesis 2 idea that our bodies are made for love and oneness. First, with a metaphor about food — he quotes something someone from Corinth has said justifying using our bodies for whatever desire we see fit (1 Corinthians 6:12–13). Their idea is that if our bodies are meant for food, and food for our body, and it is all going to be destroyed, should we not just eat whatever we want?

This is clearly a metaphor for sexual immorality — literally porneia. Paul says our bodies are not meant for idolatrous sexual desires and behaviours, but for the Lord (1 Corinthians 6:13). What we unite our bodies to matters, because we are already united to God via the Spirit. We are not meant to join God to people not joined to God — or whom we are not united to in marriage — through sex (1 Corinthians 6:15–16). He particularly has temple prostitutes in mind in Corinth, but our approach to sex in the modern world is no less idolatrous.

Some want to see “the two becoming one flesh” in Genesis 2 as about kinship — and “one flesh” language can describe family — but Paul clearly reads Genesis as about a union of bodies created through sex.

What we do with our bodies — what we unite them to — shows who we belong to. This is the New Testament case for marriage being between a male and a female — ideally between other temples of the Holy Spirit. Marriage of male and female bodies is a way to live according to our origin story that tells God’s story of two different kinds of image-bearing people — male and female — being united in love the way Adam and Eve were, but also the way Jesus and the church are, as Paul puts it in Ephesians where he again goes back to Genesis 2 and two becoming one flesh to say this is a picture of Jesus and the church (Ephesians 5:31–32).

How we use our bodies — how we pursue our desires, or do not — reflects our love for God, and God’s love for us. At the same time it teaches us about God’s love. So we should flee sexual immorality because we are sinning against our bodies; we are rewriting our scripts, and our desires, and the story we belong to (1 Corinthians 6:17–18) — when instead we should be honouring God with our bodies. For Paul this shapes how we use our bodies sexually, or do not (1 Corinthians 6:19–20).

He quotes another thing they have written to him about sex and says that married couples should have sex — with each other — to avoid immorality, and as an expression of their union. The way they use their bodies — as husband and wife — should be an expression of mutuality, belonging to each other, giving to one another in love, not just a one-way street. Married people are not our own (1 Corinthians 7:1–4). Notice too, his teaching here is not just about male desire and a wife’s duty to her husband — or just a wife’s consent — it is a dynamic of mutual giving to each other, not taking.

Paul, who is single, then unpacks a little more how being a “eunuch for the kingdom” plays out — he wishes everybody could be single like him; enjoying singleness as a gift from God (1 Corinthians 7:7–8). Imagine a world with compulsory sexuality grappling with this idea — maybe you find it hard to believe singleness is good — better, even.

Paul explains that he wants people to be freed from worldly concerns to set their hearts on God. He says an unmarried man can devote himself to God, while a married man will be concerned about pleasing his wife — rightly, I take it. An unmarried woman can devote herself to God — body and soul — while a married woman is concerned with pleasing her husband — rightly, I take it (1 Corinthians 7:32–34). Paul would love people to be able to give undivided devotion to God (1 Corinthians 7:35). This is life lived for the kingdom of heaven.

He will go on to talk about how Christians approach food and drink in idol temples, not making their bodies one with idols (1 Corinthians 10:20–21), and how they eat the Lord’s Supper in ways driven by sensuality and self-belonging and self-importance, rather than ways that recognise the body of Jesus and the way his death has brought about not only the redemption of our bodies through the forgiveness of our sins, but also the Spirit now dwelling in us (1 Corinthians 11:20–21). Therefore, they should eat differently — in ways that express we belong to each other (1 Corinthians 11:29, 33).

Life in the community of Jesus involves eating together — there is a sensuality in eating together — and this is meant to teach us about God’s love, just like the fruit trees in Eden, and to generate life and love in us so that we live together, with our bodies, as the body of Jesus. We remind ourselves that we are not our own. These practices with our bodies — practices of worship — are meant to shape our loves.

Honouring God with our bodies is not just going to be a result of new thinking, but of new practices that cultivate new desires — new worship — as people whose bodies are now temples of the Spirit; dwelling places of God, who are being transformed into the image of Jesus. This might mean letting the Spirit point our hearts towards heaven.

Here is where Taylor’s idea of a buffered self is interesting. Think of buffers as putting up walls. I reckon every time I consciously engage my body in idolatrous sin in the pursuit of fulfilling my desires, I have to deliberately shut my heart off to God. I have to pretend he is not in the picture, or that he does not care. I cannot serve two masters, and in those moments I am choosing to be the master — or, really, I am being mastered by desire.

We have to embrace being unbuffered; being open and vulnerable towards God — to live in the reality that he lives in us, all the time — and so to involve God as we use our bodies; as we pursue our desires.

Sarah Coakley describes prayerful contemplation as an act of openness — vulnerability — to divine action; where we allow ourselves to cooperate with the promptings of divine desire, trusting the Spirit will intervene for us and in us as we pray:

“Contemplation is an act of willed ‘vulnerability’ to divine action. In it, one cooperates with the promptings of divine desire… The contemplative encounter with divine mystery will include… an often painful submission to other demanding tests of ascetic transformation — through fidelity to divine desire, and thence through fidelity to those whom we love in this world.”

Coakley, God, Sexuality, and the Self

She calls this a submission to a master — to God — where we undertake tests of ascetic transformation (discipline and self-denial); being transformed by letting go of selfish desires and action, and aligning ourselves with God:

“What we discover in the adventure of prayer, in contrast to these other routes, is a gentle but all-consuming Spirit-led ‘procession’ into the glory of the Passion and Resurrection, a royal road to a ‘Fatherhood’… Here, in divinity, then, is a ‘source’ of love unlike any other, giving and receiving and ecstatically deflecting, ever and always.”

Coakley

She is talking about a prayerful practice where we invite the Spirit to lead us into the life and love of God in those moments where our desires might pull us from God. This all sounds mystical and weird until we remember we are temples of the Holy Spirit. Imagine yourself pursuing a desire — sinful or otherwise — and ask how conscious you are of God’s presence; how much you are seeking to honour him in those moments. How willing are you to be led by the Spirit in those moments, and what might it require to open yourself to seeing your body and your desires this way? It feels abstract until you imagine whether this sort of openness to God will lead to more honouring God with our bodies, or less — more love for God, or less.

I think this has implications for how those of us who are married use our bodies in marriage — where honouring God and seeking to teach one another about love in ways that are vulnerable, mutual, and not autonomous is key. We can bring buffered selves to our intimacy — pursuing our own gratification through others — and as a result fail to find intimacy. What might it look like to bring an openness to God and a desire to know him into our intimacy? And what might it look like to direct unfulfilled desires towards God in the same way, taking them to him in vulnerable prayer, trusting that they are God-given with the purpose of being God-directed?

This is the ascetic life of disciplining our desires. But I think we also need a new way of approaching aesthetics — a way of responding to beauty that turns us heavenward before desire kicks in.

There is something in what Paul says in 1 Timothy: when we are confronted with our desires we can respond by forbidding people to pursue desire — as people were in the first century — but Paul’s point is that God makes good things — beautiful things — and he makes good things to be enjoyed on his terms and received with thanksgiving (1 Timothy 4:3).

There is a Christian purity-culture practice that Angela Chen writes about in her book — you might have heard of it — a practice that teaches men struggling with lust to, when they see an attractive woman — or man — “bounce their eyes” straight to the ground:

“Readers are instructed to ‘bounce your eyes’… which means immediately looking away from anyone who might trigger an impure thought. Visual repression starves the sexual appetite, supposedly.”

Chen, Ace

This ends up sexualising all attractive people as much as leering at them. Imagine never being able to make eye contact with another human because you cannot control your heart.

Maybe a better practice is not to bounce our eyes to the earth, but to raise them to the heavens and give thanks to God for beauty that is not ours to possess.

I have loved this idea since I read it in something Alan Noble wrote; he talks about a “double movement” — first acknowledging beauty where we find it, and then opening ourselves to God in that moment, turning to God in thanksgiving in ways that help us to love our neighbours. I have found this helpful in those moments I have managed to live as an unbuffered self, led by God’s Spirit in me, rather than the desires of my flesh:

“Simply put, the double movement is the practice of first acknowledging goodness, beauty, and blessing wherever we encounter them in life, and then turning that goodness outward to glorify God and love our neighbour.”

Alan Noble, Disruptive Witness

Maybe this is what it means to receive good things God has made with thanksgiving and consecrate them through prayer so that our desiring hearts are set on God.

Leave a Reply