Somewhere in the notes on my phone I’ve started jotting down the different labels people are applying to modern life; post-modern, post-Christian, post-truth…

Post-truth was the Oxford Dictionary’s word of the year in 2016, where it means:

“‘Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief’.”

I’m not an expert on anything much (just making coffee and how to write obscenely long blog posts really)… so I assume when I write stuff people will take or leave it based on its usefulness or truthiness or whatevs. This is something of a caveat or a disclaimer on this post; an acknowledgment that these aren’t definitive things for me inasmuch as they’re the building blocks of how I’m approaching life in the church in however you’d describe modern Aussie life… the nature of time moving forward and different cultural and intellectual epochs being left in the past is that we’re always ‘post-‘ something; at the moment it’s hard not to feel like we’re post-everything; when I talk to different people both in and outside the church there’s a sense that life is changing pretty fast and there’s a temptation to either try to change the church (and what it looks like or does) just as fast to keep up, or to not change how we do things at all. I suspect both these options are wrong and right (at the same time); that we need to change pretty rapidly, but that the change shouldn’t be ‘innovative’ purely for innovation’s sake where we copy the culture only with a bit of Jesus tacked on… it should almost be a rediscovery of who we’re meant to be.

I’ve written a little bit about different approaches to our post-central position in culture (as the ‘church’) and an idea being developed and put forward in the US called The Benedict Option first considering the church as something like the mutants in the world of the X-Men, then considering the post-everything culture as a sort of zombie apocalypse where we’re wanting to survive and thrive; which is a return to a sort of monastic approach to life in the world; not total withdrawal, but a sort of firming up of community boundaries so that mission seems to involve people coming in to our community more than it involves us living as people sent into the world to be a faithful presence… I’m not sure this is the answer to our post-whatever milieu, or what life as exiles should look like (which I think isn’t just the paradigm for life-post-Christendom but for life-post-cross), but part of what I’m trying to sketch out as I write, for myself perhaps more than for others, is a framework for thinking about the life of the church — the body of Christ — in this world; my assumption is that the church should be proclaiming and living the good news of the kingdom of God and its king, Jesus, and that this is fundamentally counter-cultural, it is its own post-everything community, this shouldn’t feel like a call to a new ‘reformation’ in the Aussie ‘evangelical’ scene, though in some ways it is.

There’s not a heap of ‘new’ stuff in this post; what I’ve been aiming to do with this little corner of the Internet for a while is articulate how I’m approaching life and church as much for my sake as for anyone else’s, as a way of tweaking and working out my paradigm. That means there’s a fair bit of repetition, but it also means the archives here chart the development of my thought, which I find personally useful… if this stuff is useful for others along the way, then that’s a bonus.

So here, to perhaps clarify about 50,000 words of previous posts on this blog, are 14 propositions and 3 stories on what I think church can and should be in a post-everything world. It’s long. I’m assuming you’ll skim read if you bother, but part of this is to have a comprehensive one stop shop that spells out my approach to being the church in the post-truth age. I don’t think these are new ideas, though they might be old ideas applied to new threats and opportunities. The stories aren’t meant to be heroic, they are, however, reflections on where I’ve felt like things have ‘clicked’ for our church in the last few years. There are lots of stories, good and bad, from three years of church stuff, these are the ones that fuel the ‘propositions’…

Story 1.

For the last three years (it’s our anniversary in a couple of weeks), I’ve been the campus pastor of Creek Road South Bank. One of my greatest privileges in that time has been baptising 16 Iranian brothers and sisters in Christ. Before I baptise anyone it’s part of my job to hear the story of how they came to follow Jesus (and to ask questions to make sure to the best of my understanding I’m pouring water on Christians). These 16 people share a few things in common: they’re all asylum seekers who arrived in Australia having fled Iran with a particular suspicion about Islam because of the Iranian regime, they’re all able to overcome the language barrier enough to answer my questions about the Trinity (which is a thing I probe because it’s a big difference between Christianity’s view of God and Islam’s), they understand the Trinity, they get the significance of the death and resurrection of Jesus for their standing before God, and they’ve universally told me that the reason they began investigating Christianity, and stuck with it, is the love they received from Christians from when they arrived in Australian detention, to when they’ve been resettled in the community, to when they’ve met Christians in church. I can’t take any credit for anything except that I ask questions and do the water bit; but I’m so deeply encouraged, every time, not just by the ‘homecoming’ involved for these brothers and sisters, but by their simple testimony that it’s loving, gospel-shaped, community that makes the Gospel seem worthy of investigation.

Proposition 1: Media matters: You are the social media for whatever you worship

We’re made in the image of God and part of that is that we’re designed to worship and so represent God in his world as his living, breathing, imagining, creating, life-giving people; we replace God with dead idols that take our breath away and we end up adopting new ways of dying based on what it is we worship (most people are poly-theists when it comes to idols, worshipping from a sort of smorgasbord of ‘gods’ like family, money, career, sex, power, popularity so we all look a little different).

Proposition 2: Our ‘media habits’ matter: our worship involves our habits (our repeated actions), which feed and shape our loves and our thinking.

There’s an aspect of ‘post-truth’ stuff that we need to recognise is a misfiring of some fundamental parts of our humanity; we’re made to love and feel our way around the place — but we are, as Augustine might put it, disordered lovers; our media habits — what we fill our time, our attention, our imaginations with and do with our bodies shape us. We live in a world that’ll be increasingly shaped by content-on-demand TV which we binge watch on our couches while eating convenience food (where we’re totally disconnected from the process of the food getting to us), by pornography, by addiction to black glass screens that bombard us with content and fill our attention from the moment we wake; by buying ourselves (fleeting) happiness, and shaped by the equally idolatrous over-correction — those who see the problems with this way of life and so live sort of monastically ‘disconnected’ lives focusing on the pursuit of the perfect meaningful romantic/sexual relationship, ‘slow-food’ that you grow and hunt yourself that you prepare following the recipe of a celebrity chef, or buy from a fancy locavore restaurant, with lots of silence and mediation thrown in for self-mastery’s sake. We are all somewhere on the spectrum between Biggest Loser and MasterChef.

Proposition 3: We live, worship, and image bear both as individuals and corporately/culturally/in community

Bearing the image of the God who is a community (the Trinity) is not something we can do alone even if we try, and it was never a thing we were meant to try; we’re relational/social animals. That’s why God says ‘let us make mankind in our image’ and then makes us male and female… We’re defined as much by relationships with others as by whatever ‘image’ we try to craft alone; and even as we craft an image for ourselves and so worship in particular ways, that’s inevitably a thing we do in community with others that is shaped by the culture we define ourselves through or against. ‘Cultures’ are the product of a sort of coherent mass of ideas and artefacts that tell some sort of story about life and shape the way members of a culture ‘worship’.

Proposition 4: All ‘media artefacts’ have some sort of ‘story’ or value proposition and collections of these artefacts make ‘cultures’

In the past idols had ‘statues’ to represent them; now idolatry seems to happen more through a collection of ‘widgets’ or artefacts that stories or the sort of things we use in stories, that equip people to pursue their worship. I like Andy Crouch’s insight that cultures are a collection of ‘artefacts’ with some sort of coherent story.

Just like God’s ‘art’ — creation itself (and us) — is made with the purpose of representing true things about him… Art, whether written, performed, or fashioned isn’t neutral, it’s made with purpose and represents ‘true’ things about us. The technology (whether hardware or software) and ‘media’ we create are types of artefacts,’ they aren’t neutral. We can always take and repurpose things to use for good, Godly, purposes, just as we took God’s world and used it for our bad purposes; but we need to be aware of what’s under the hood.

So, for example, ‘slow food’ might actually be a better way to articulate true things about God’s world than fast food (just as specialty coffee is better than instant coffee), but we need to make that decision with imagination, discernment and clarity (and applying the same to other ‘artefacts’ in order to be creating an alternative ‘culture’. We need to find a way to ‘plunder Egypt’ for golden ‘artefacts’ that are good and true and beautiful that become part of our ‘culture,’ but we also need to beware the human tendency to use Egyptian gold for golden calves (we take the good stuff God made and use it for our own idolatry). We also need to figure out how to make stuff with gold — our own artefacts — in ways that line up with God’s purposes for creation. Christians could be making things that are good, and true, and beautiful both on a local (neighbourhood) type scale, and on a ‘global’ scale, for the good of everyone not just for our own Christian marketplace.

Most people in our culture don’t think of themselves as worshippers, but that doesn’t mean they’re not. They don’t think of themselves as being searchers for ‘truth’ or meaning (like the people of Athens) and part of our culture-making probably has to be question-provoking; it might have to carry a degree of oddness or mystery that makes people ponder why we’re so different (but in a way that is compelling because it is linked to helping people rediscover the created purpose of our humanity. We also can’t take for granted that people will have any of the conceptual building blocks of the Christian story where that might have once been the case.

Proposition 5. Our aim isn’t to smash idols with sledgehammers (except in our own lives perhaps) but to hollow them of meaning and value, and to show how the inclinations of our hearts that produce them are better satisfied in a better story, with a better God.

In Deuteronomy Israel are told that upon entering the promised land they should totally destroy the idols of the nations; lest their hearts be captured by them. That’s a guide to life in God’s kingdom in Israel; there’s a particular socio-political reality underpinning that approach to idols. In the New Testament Paul tells us to keep ourselves from idols; basically to smash them within the boundaries of the church. He takes a very different approach to the idols of his culture. In 1 Corinthians he tells the church to eat food that has been sacrificed to idols in the presence of non-Christian friends or family who are hosting dinners until the host makes such eating a specific kind of participation in idol worship; until they make a big deal about the sacrifice in a way that makes eating some sort of participation in worship that confuses the people you’re trying to invite to an alternative type of worship. In Athens, Paul walks the streets of the idolatry capital of the world without a sledgehammer; and when he gets the opportunity to speak he doesn’t tell the Athenians to knock down their idols, he understands the human impulses that have led them to worship the wrong thing; to imagine different gods as the solution to their desires, and he attempts to redirect those impulses to the true God in a way that shows their idols as foolish distractions; he does this by quoting the poets and philosophers of the time, he shares as as many assumptions, as much empathy, or as much humanity, as he can with those he is preaching to, without joining their worship. The effect of this is to, much as the Old Testament prophets did when writing about ‘breathless’ idols, hollow them of any legitimate value or meaning, by pointing to the truly valuable God, the one ‘in whom we live, and breathe, and have our being’… his preaching of the more valuable God has a profound impact on people in this ancient world. When he gets to Ephesus a couple of chapters later, the same preaching causes a bunch of people to switch to worshipping the Christian God, and so to burn incredibly valuable (idolatrous) magic books. The impact on the idol-making market — because of the way the Gospel hollowed out the value of the idols of the time — is so great that the local idol making cartel starts a riot to push Paul out of town.

“About that time there arose a great disturbance about the Way. A silversmith named Demetrius, who made silver shrines of Artemis, brought in a lot of business for the craftsmen there. He called them together, along with the workers in related trades, and said: “You know, my friends, that we receive a good income from this business. And you see and hear how this fellow Paul has convinced and led astray large numbers of people here in Ephesus and in practically the whole province of Asia. He says that gods made by human hands are no gods at all. There is danger not only that our trade will lose its good name, but also that the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be discredited; and the goddess herself, who is worshiped throughout the province of Asia and the world, will be robbed of her divine majesty.” — Acts 19:23-27

This is what we should be aiming for; to acknowledge our desire for life, meaning, joy, comfort, and significant relationships and to rob the idols of the present of their value because they don’t provide actual answers. Not with a sledgehammer, but by offering something better. One of our age’s own poets, David Foster Wallace, in the speech This Is Water (which I quote all the time (because it’s the equivalent of Paul quoting the non-Christian philosophers at the Areopagus cause they were so close to getting God right) points out that our culture has its own ‘cartel’ of idol makers; the powerful and influential systems and leaders who get more wealth and power so long as we all mindlessly participate in the default worship of our culture; which he calls ‘the worship of self’ — and which he suggests manifests itself in the worship of sex, money, and power. This is our Athens:

“And the so-called real world will not discourage you from operating on your default settings, because the so-called real world of men and money and power hums merrily along in a pool of fear and anger and frustration and craving and worship of self. Our own present culture has harnessed these forces in ways that have yielded extraordinary wealth and comfort and personal freedom” — David Foster Wallace, This Is Water

Our job is to afflict those who have become comfortable via these defaults, and to comfort those afflicted and oppressed by these defaults, but to do it not by taking a sledgehammer to the sort of idol-perpetuating cultures (like capitalism and power-politics) but by offering a better way; a way that shows that the promises of ‘gods’ other than the one we see nailed to a cross, have no ‘divine majesty’ but are hollow and life-taking.

Proposition 6: The ‘post-truth’ world should rightly refocus us on ethos (and even pathos) as part of Gospel proclamation; it’s what gives our message integrity, credibility, and appeal

One of our misfires in the ‘truth’ world has been to assume that truth is found in the realm of ideas and words; that it’s a thing you predominantly think and that our heads lead to change; that we’re sanctified via education alone. We’re not just logical brains, or computers (I’ve heard some interesting stuff from brain scientists about how unhelpful it is to treat the brain as a ‘fascinating computer’ and I think we’ve made this mistake in our approach to church; trying to get the programming right). We love and feel and experience truth. Ancient communications theorists were all over this — logos (words/logic) alone is a terrible and unpersuasive ‘proof’… when we add the stuff about us being visible media into the mix (and think about how God communicates via visible media from the creation of the world, to laws that produce rituals and story-telling celebration, onwards to the word being made flesh in Jesus), it’s hard to get to a position we’re our words aren’t being given their weight and meaning by our actions and character. Words are always necessary; not just because we do think logically, but because words are also part of the way we calibrate our hearts. Words are something fundamental to our humanity; something we share with God that animals don’t (unless we teach them to parrot us), but we need to think more about the sorts of words, and about how words that have integrity have integrity because they line up with actions. Tying the above propositions together; this ethos is a thing we share across the church community, not just an individual thing.

Proposition 7: The church is the plausibility structure for the Gospel

Because persuasion happens via ethos as much as the logos that shapes it, and because that’s corporate, and because worshippers represent the God they worship, it shouldn’t surprise us that communities built around gods make those gods plausible. This is true of the shopping centre, where the story of happiness via consumption is told/pursued by all the people shopping together (or together alone) and shopping in ways that follow ‘trends’ (which often feature cultural artefacts that everyone wants to buy and own and attach to their ‘image’). The church community is where the Gospel is displayed as it is lived and articulated.When we forgive each other for wrongs and hurts we inflict on one another by bearing the cost of wrongdoing on ourselves we show the truth and goodness of the forgiveness Jesus pours out on us in his death.When we respond to messy sin with grace, rather than disgrace or shame the person (in a way that is utterly counter-cultural in our new shame culture) we make the Gospel more believable for us, and them.

When we have permission to be broken and vulnerable but are treated as though we have inherent dignity and value in the life of the community we make the claim that we are loved by God and being transformed into the image of Jesus feel true.

When we love each other the way Jesus loved us and commanded us to love — for the sake of the other, not our own sake — that makes the love God displays for us in Gospel believable for us and for others.

This isn’t revolutionary thinking either; it’s there in the words of Jesus when he says “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another…” (John 13:35, which is basically the idea that underpins the whole of 1 John where the possibility of continued belief in Jesus, and loving like Jesus are linked inextricably). Discipleship is about formation; we’re all disciples of whatever god we worship, shaped by those who are more ‘mature’ worshippers because it comes via imitation not simply education; for Christians it comes via imitation of Jesus (to love as he loved, which is also what he commands us to do in John 13:34: “A new command I give you: Love one another. As I have loved you, so you must love one another…”).

Proposition 8: For the Gospel to be proclaimed/plausible/lived 24/7 (not just on Sundays) we need to think of the church (community of believers) and its worship (corporate activity of sacrifice/service of God) as being a 24/7 thing not a two hours on Sundays thing.

We humans are worshippers 24/7. We’re always giving ourselves to our gods and getting shaped by them in return. Worship delivers transformation (and often disappointment, or in the words of David Foster Wallace, worshipping idols ‘eats us alive’…). To make the Gospel plausible in post-everything Australia we need to be quite deliberately combating other types of worship in how we live 24/7; a get together on Sundays for an hour or two won’t cut it because it won’t display our ethos (the Gospel enacted in the love of Jesus) for long enough to be plausible for us, let alone for others. This will mean deliberately building different rhythms into the lives of Christians to the rhythms we adopt without realising as we live and breathe in idolatrous post-everything air.

Proposition 9: In this model of corporate proclamation (ethos and logos) by the church all the time, the priesthood of all believers really matters; which requires an upping of the levels of commitment of ‘unpaid’ church members and lowering the commitment of paid staff.

If corporate ethos really matters; and the church community speaks, lives and breathes the story of the Gospel to ourselves, and the world, then it’s hard to outsource the ‘ministry’ of church to a handful of paid professionals. That’s been an unfortunate part of seeing church as predominantly a Sunday thing; ‘serving’ at church becomes less important than ‘being served’ or ‘consuming’ a ‘worship event.’ And all of that is wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong. There’s certainly a case to be made for paid church workers (quite explicitly in the Bible) and I definitely think I offer some value for money to anyone considering reading this point and not giving at church anymore… there’s also a case to be made for a significant portion of a church’s budget being used to free people up from secular work to pursue a gospel calling. We’re all, as Christians, called to Gospel ministry (which means service), and this will take different shapes based on our gifts, circumstances, and maturity. What this ‘call’ looks like will be different for everyone, and it’s important that we don’t enforce some sort of secular/sacred divide here; a Gospel ethos underpins the work of the cobbler as much as it underpins the work of the preacher.

Work matters; but seeing your work (including what you choose to do) and how you do it as part of your ministry (not just your colleagues as people to bombard with Gospel ‘logos’) is part of making work truly matter.

Part of ensuring that church/worship of God/being the body of Christ is the most fundamental part of setting the agenda of your life might involve you having that agenda less set by work (and the imperatives of our modern idols of career, money, comfort and power); this might mean resting, recreating, and relating more with the people in your life, of changing career, or going part time and figuring out how your gifts might be more directly used for the Gospel.

Story 2.

In the first couple of weeks of meeting in the Queensland Theatre; one of the brilliant theatre company staff who was tasked with helping us out happened to mention that their ‘charity partner of choice’ was a local social justice group called Micah Projects who run an apartment building around the corner from us which provides permanent supported housing for formerly homeless and low income people. It turns out Micah was founded as the social justice arm of the local Catholic church, but it has sort of taken on a life of its own since then. I thought that sounded like a great opportunity for us to join something already happening in our area and to practice the sort of cross-shaped ‘ethos’ the Gospel creates in us. So I volunteered. I’ve been volunteering for almost three years now, and have been part of a cool project (including the launch of a social enterprise cafe). But I’ve mostly spent time hanging out with Micah Projects’ passionate and capable team. A lady in our community got a bit excited about Micah, and she volunteered too. She volunteered for a project face-to-face with residents of this apartment building and set about faithfully and enthusiastically loving people. Others from church started attending a community meal. This lady is so warm and genuine in her love for others; a love that crosses barriers, that soon a resident of this apartment building, a lovely older lady (perhaps more enthusiastic about life than even our volunteer) started coming to church. She’s not originally from Australia, has no other family here, and now, in her emails and in conversations with people from outside our church calls us her ‘Aussie family’…

Proposition 10: As an alternative ‘community’ with an alternative king and alternative ethics (ethos), the church is profoundly ‘political’ (and both ‘progressive’ and ‘conservative’ at the same time).

The church can’t simply attempt to be an arm of the secular state; wielding worldly power as though we’re not profoundly different to our neighbours. We follow king Jesus and are ‘citizens of heaven’ who ‘live as foreigners and exiles’ in this world; but nor can we pretend the Gospel is apolitical; that following Jesus has no bearing on how we live in God’s world amongst people now. The word ‘politics’ originally meant: “of, for, or relating to citizens” and we have some very big ideas about what it means to be citizens of God’s kingdom; to follow Jesus, to obey his commands, to: ‘‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ and ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’

The Gospel gives us a new vision of ‘the ethical’ and ‘good’ human life; which in the context of relationships/community gives us a new ‘politics’ — the word Gospel is, in itself, a political statement that Jesus is king (that’s what a ‘gospel’ was in Rome). Being part of God’s kingdom, the church, brings a whole new way of doing politics that come from our understanding of what the good life for a citizen looks like; the sort of life we aim to live as we follow our king, but also the sort of life we hope might appeal to others and commend the Gospel to them (not the sort of life we want to coerce people into living without a regime change in their heart).

Our understanding of what it means to be human means we see humans as made in God’s image; so that there are certain inherently good and natural things that we commonly hold together (a sort of divinely inspired moral compass), so we’ll naturally want to conserve those things in a shared approach to life together as citizens; but we also see humans transforming themselves into the image of destructive idols via corporate/cultural replacement of God with created things, and we see that as profoundly damaging to our humanity (and to others) (Romans 1). We’ll see most cultures/institutions as being produced by image bearers who are also idolaters and so on a sort of spectrum towards deathliness depending on how much they’ve been given over (together) by God to the consequences of rejecting him (Romans 1) — people who know what they should do, but often don’t do it (Romans 7), so we’ll naturally want to call for a sort of progress away from that broken humanity towards the example of humanity we see in Jesus. We’ll call for this without expecting people who don’t follow Jesus to adopt that ‘progress’ for themselves, and we’ll call for it loudest by living it as people/citizens being transformed by God’s Spirit (Romans 8).

This means there might be things Christians can achieve for the love of God and neighbour through involvement in conservative or progressive human political institutions as an outworking of our alternative politics; it might also mean not being part of those systems; it definitely means our first allegiance is to Jesus and his kingdom, and it means having our ‘politics’ first shaped by this citizenship.

Proposition 11: Part of the nature of the Gospel’s ‘ethos‘, the nature of our politics, and how we see the value of people and the use of power, pushes us towards the marginalised in our community not towards occupying or cosying up to ‘powerful’ worldly leaders (and for those of us in positions of power and influence should shape us to use that in particular, sacrificial, ways on behalf of the vulnerable).

The way Jesus uses power is the anti-thesis to the way the Serpent, Satan, uses power and following Jesus brings with it a new way of approaching power that isn’t the grasping, self-interested approach introduced by the Serpent in Genesis 3. The way of the Serpent is the way of the ‘beastly’ Roman empire (see Revelation); it’s the way that culminates in humanity driving big metal spikes through the hands of God With Us (Jesus), and killing him on the best weapon of utter humiliation-via-powerlessness that humanity could devise. The cross worked by robbing someone of their dignity and their ability to inspire (both in terms of breathing or leading). That’s why Rome used it to punish treason and insurrection; it was meant to give Caesar more power by robbing power from pretenders. The serpent makes powerful people into crucifiers; Jesus makes people cruciform (cross shaped). This orients those who follow Jesus to a particular understanding of how sinful people (and cultures) will wield power for their own self-interest, and attunes us to the sort of cost that inflicts on the people who powerful people use to their own ends; it means that we use our own ‘human power’ as a gift from God to be poured out for the sake of others; whether we occupy an ‘office’ that brings a degree of authority, or we’re just human, there’s an orientation towards the poor, the enslaved, the widowed, the oppressed, the vulnerable, the abused, and the victim. Most people are ‘marginalised’ in some way by the use of power, because ultimately power used to our own selfish ends is power being used by ‘that great serpent’ whose reign is destroyed by the reign of Jesus (again, see Revelation).Part of the ethos that comes with serving the king who lays down his power for the sake of others to make a ‘home’ for the marginalised and re-affirm their dignity will involve us pursuing justice and mercy and love for the marginalised in our world; not in a way that tosses out the truth that we’re all ‘marginalised,’ excluded, and exiled, from God by our sin (a trap the ‘social gospel’/liberation movement fell into), or that sees this as the only marginalisation that matters (the trap the more fundamentalist ‘preach heaven to the dying world’ movement falls into) or that our homecoming to God involves being ‘exiles’ from the world of human/serpentish power (a trap a sort of ‘reconstructionist’ approach to government falls into sometimes), but in a way that sees how we live and love being part of how we proclaim and live the truth of the Lordship of Jesus over all things.

Proposition 12: We are ‘narrative animals’ and it’s stories that underpin our worship

As people we occupy space and move through time; the thing that separates ‘narrative’ from other forms is that events that happen in space, over time are understood/told that way. That’s how a story and a statue convey meaning differently. It’s also the difference between a computer and a person. When I turn on a computer it has no deep knowledge of the idea that it has been turned off for days, weeks, months or years, or that it is in a different place (even when software options recognise those things for us as users, they’re not ‘meaningful’ for the computer itself). We’re ‘narrative animals’; the post-truth thing where ’emotion,’ intuition, and our ‘personal narrative’ trumps facts is, in part, a corrective against a view of people that treated us more like computers who just had to be programmed right in order to perform right.

Plausibility in a post-truth world means treating people ‘narrative animals’ who organise our passing through time and space by telling stories that help us understand, love, feel, and intuit our way around the world; and telling a better/more-compelling story that brings a vision of what life should look like; it’s these stories and this vision that will shape our habits and loves, and so shape us.

These stories use words, but they’re also lived. Part of the task of the church community is to be a story-telling community in word and action; a community that lives and breathes the story of the coming of the kingdom of God and the death of sin and death in Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. Stories go hand in hand with ‘history’ — the collection of stories over time that give an account of who we are. There’s a movement called the “Big History Project” which aims to equip people to live more scientifically in a post-truth world by starting ‘history’ teaching with the big bang and giving people a sense of the tiny amount of space and time we occupy; we’ve got a better big history, that also begins with creation, but centres on the God who spoke the universe into being showing his incredible love for us and making us eternal. We should tell that story (like Paul does in Athens in Acts 17) as a way to move people from worshipping idols to worshipping the true God; because he’s actually a better God with a better story to be part of. This has to shape the way talk about the Bible (as a story not a weird collection of rules and facts, which is actually truer about how the Bible seems to understand itself — and how the apostles preach the Old Testament in Acts).

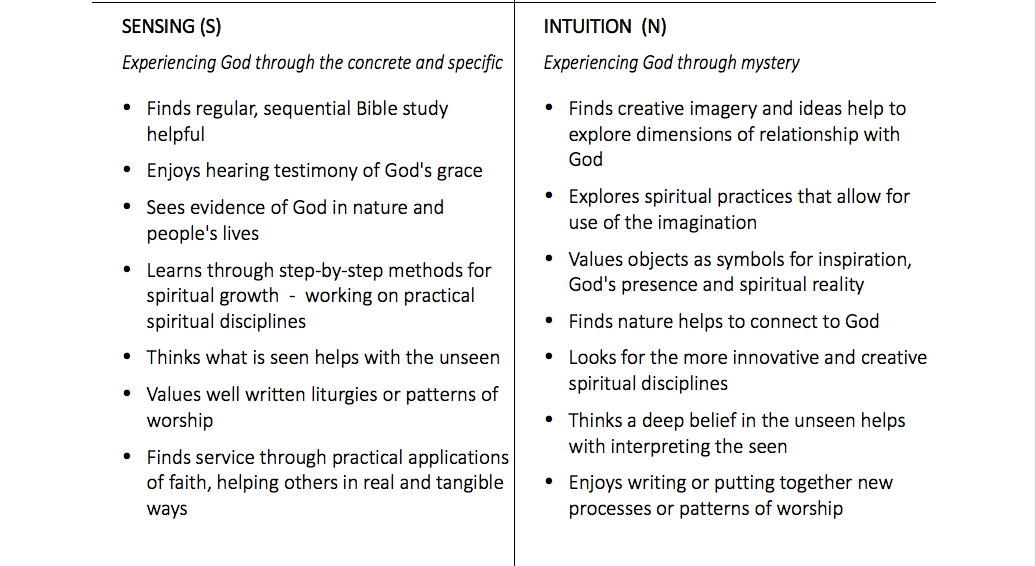

Proposition 13: Because we’re worshipping ‘narrative’ creatures who understand our world and are formed through ‘story’ and action (ethos) in community, not simply detached ‘facts’ (logos) Christian formation happens through the hands and the heart (our loves) as well; so we can’t just ‘educate brains’ to make disciples.

This is just Augustine and James K.A Smith and the implications of the stuff above. We become what we worship; and worship is about much more than simply knowing. I know I should eat healthier and that will re-shape me; but until I love the idea of a healthy me more than sugar and junk food and habitually say no, the knowing does nothing, and I know sugar is bad for me the less I eat it… If it doesn’t work in dieting (or any realm of human behaviour built on producing a changed image) why do we think formation happens purely by education? The implications for this are massive in terms of investment of time and energy in the rhythms of church life (the sermon can’t possibly be enough), but also changes the things we say when we preach and where we pitch stuff. The caveat is that of course the head is important; it’d be a weird sort of irony to write this much and not acknowledge that.

Proposition 14: Propositions are dead.

Propositions are a reasonable way to do logic, and they were perhaps okish in a pre-post-truth context (particularly in a modernist context). They’re a reasonable way to argue. I’m not so sure that many people have been argued into the kingdom of God (though I’m sure some arguments have been part of getting people to consider Jesus)… I’m fairly sure arguments/debates/logic won’t do much if the post-truth thing is the spirit of the age we live in. It’s still important to have some sense of the logic of belief in Jesus, but that won’t be the thing that gets someone to check out, or believe, the Gospel at a gut, or heart, level.

Propositions are actually a terrible way to do anything that looks like ‘change’ in the scheme of things whether that’s in the life of individual Christians, or in how we do church. And as much as a very long post on a blog might seem like a lot of energy to invest in a thing that doesn’t work, I’m much more interested in investing my energy into demonstration of this stuff in the context of the church community I’m part of, and through telling stories. There’s, of course, an irony in all this, but these propositions have largely been derived from how I understand the story of the Bible works, and from my observations of stories of God at work in the lives of real people in our church, lives that reflect this grand story…

Story 3.

In the beginning, God made a good world — an ordered and beautiful world where every created thing had a built-in purpose. It’s purpose was to reflect his goodness, his character, and his love. It was a gift for his children; his image-bearers. He made us to represent him, to rule with him, to spread and create things that would reflect his goodness throughout the world. He made us with another job in mind — as men and women — he made us to take part in the cosmic battle to defeat evil. Evil personified in the Serpent. Satan. He gave humanity what was required to defeat him; simply the opportunity to choose good, not evil, when the serpent came knocking. That would’ve been his end. Perhaps the serpent might have struck out and killed humans, but God has always been the life-giver who is capable of resurrection, and the gift of immortality via the ‘tree of life’ is part of his expression of love for his children. Who knows? The serpent struck with his words, not his teeth, he invited us humans to replace God with a false picture of God… first by suggesting that God wasn’t a generous life-giver who gave people everything they need, and more, and then by inviting them to decide what ‘image’ of God, what likeness, they would present in the world God made. Stuff God. Do your own thing. Worship some other picture of wholeness and goodness and pursue that. Only, none of these give life, or breath, or being; instead, they take life and breath. And that’s what humans choose, by default, to be our own gods, to worship false gods, to pursue satisfaction in using the things God made to our own ends. And it’s not just not-satisfying (it always leaves us wanting more), it’s also deadly. These things don’t give life.

The story of humanity from that point is the disappointing story of hearts too easily lured away from God towards death, but God constantly pulling people from the smelting fire, re-forging them, breathing new life and purpose into them, offering life again… only for those same ‘new image bearers’ to head towards the exile door, away from him, away from life.

The Old Testament is a story of failed kings, failed states, and exile; of God’s images being captured and corrupted by foreign ideas — as idol statues often were in other military conflicts of the time — and so losing their created purpose. Of hearts turned towards wrong pictures of God, of imaginations misfiring. This is not just Israel’s story; it’s the story of humanity. It’s what we do. We’re haunted by having known the infinite, life giving God, and having lost that knowledge, collectively and culturally, by replacing him with things he made. It’s also the story of God’s faithful commitment to his original plans; the defeat of the serpent and the creation of a people who join him in spreading good, and true, and beautiful things — in spreading life itself — around the cosmos. Using our desires and imaginations; our creativity; to make things that are life-giving, not death-bringing.

The story happens all over again with Jesus. When the author of life writes the word of life into the story of the world as a character. Jesus, both God and man, a new Adam, one who will end the serpent. The serpent-killing lamb ‘slain from the creation of the world’… the one who says no to the Serpent because he knows the goodness of God. The one who defeats evil not with the might of a sword, but with the obedience of the cross… that moment in history, at the centre of the story, where he both reveals God’s character and takes on the sin, and guilt, and shame, of those who write their own godless stories. Where a good king steps in to end our exile from God and to restore images captured by foreign enemies. Where the infinite becomes finite — to the point of spending three days dead — to give infinite life to us. This life is re-breathed into his people as the Holy Spirit; a divine spark setting fire to our hearts and minds, re-shaping us into what we were made to be; not just images of the infinite, invisible God, but of Jesus. Our king. Jesus invites you to rediscover the satisfaction of becoming who humans were always made to be. He invites you to be a character in the story that brings life, rather than write your own stories that bring death; to make things (family, friends, art, work) that are good and true and beautiful reflections of God’s goodness and character — the goodness and character we ultimately see revealed in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus — with others who are being re-shaped, re-forged, by that same Spirit. This creative community is a life-giving community, a community that lives out this new story and points people to the hero, while relying on God to give us life and breath and everything, and seeking to love our neighbours the way he loved us.

This is the true story we get to tell, and the story we get to live, as God’s people living in a world pulled in all sorts of directions by different types of worship. ‘Facts’ without this story are empty, that’s why the ‘post-truth’ thing isn’t ultimately a terrible thing for Christians, but perhaps it should be a ‘game-changer’ in that it should pull us back to a way of loving people and sharing the Gospel that we should never have walked away from (and in many cases, haven’t walked away from).