This piece contains some spoilers about a minor element of the plot for Avengers: Infinity War.

There’s a plot thread in Infinity War continuing in Marvel’s exploration of parenting (see also, Black Panther, Guardians of the Galaxy 2, etc). Thanos is the adopted father of Gamora; the adoption comes in the midst of his committing a semi-genocide (killing half the population) of her planet ‘in order to save it’. Thanos’ mission to ‘save the galaxy’ what is driving his pursuit of the ‘infinity stones’ and the power they offer is a mission to make life sustainable by halving the population. It’s a vision for human and alien flourishing that he is utterly committed to in mind, heart, and action. He is willing to make big sacrifices to achieve this end, including the life of the daughter he loves; Gamora, one of the Guardians of the Galaxy. Thanos’ conviction to his mission is essentially religious; it’s the pursuit of his ‘kingdom of heaven’ in a physical sense in the cosmos, that he is willing to sacrifice and work for… even to make the semi-ultimate sacrifice; the sacrifice of a beloved child. It doesn’t appear that he is willing to make the ultimate sacrifice — himself — to achieve this end. When his mission is accomplished, he sits watching the sun set over a valley; a scene he foreshadows as ‘what he’ll do when his task is complete’ earlier in the movie. It’s clear he saw his task both as a personal burden, and as moral (a conviction he’s held since his own planet was destroyed because people refused to do hard things for the greater good)… it’s also clear he pursues his task with a sort of religious fervour, or zealotry. Nothing will stay his hand; no price is too great. It’s also clear his willingness to ‘exchange lives for outcomes’ is being pitted against the Avengers’ steadfast refusal to ‘trade lives’ (right up until Vision convinces his beloved Scarlet Witch to help him sacrifice himself for the cause of resisting Thanos’ cosmic vision). There’s a Cinema Blend piece doing the rounds arguing that Thanos sacrificing Gamora is the worst part of the movie, because Thanos’ actions in sacrificing his adopted daughter make it clear that his claims to love her are a lie.

When Gamora and Thanos arrive on the planet Vormir, they learn that in order to obtain the stone, one must sacrifice somebody they love. Gamora believes that Thanos has been beaten by this, because he loves nothing. But it turns out that, because he loves Gamora, he can, and does, sacrifice her to obtain the long-lost Soul Stone.

The idea is that, while Gamora doesn’t consider Thanos’ treatment of her to be love, in his own way, he does care deeply for her, and because he does, her life can be given up by him to get what he needs in order to complete this terrible task that he has burdened himself with. That’s a load of bullshit.

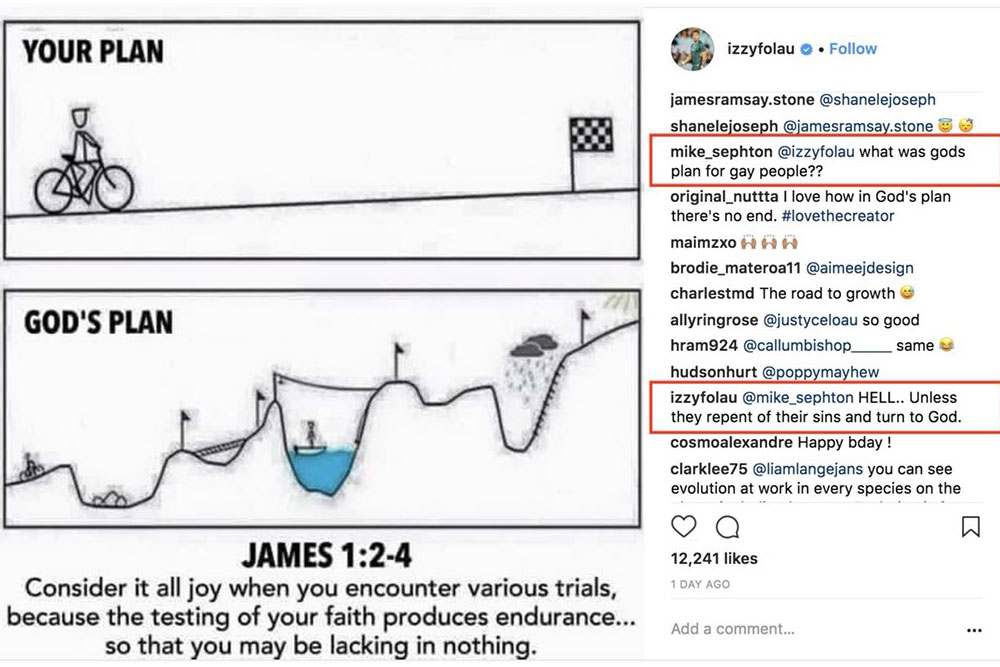

I have some substantial problems with the argument in this piece; but I think it’s revealing. We’ve, as moderns, collapsed our understanding of ‘love’ to be totalising and utterly focused on the people or things in front of us; the idea of having greater love for some cause beyond ourselves is, at least in this piece, unpalatable. For Thanos to say that he genuinely loves Gamora he has to love her above all other causes. This is tricky ground to cover; especially in a world where a family with deep religious convictions can do what a family in Indonesia did to some churches over the weekend. There’s something to the argument that unfettered fanatical devotion to a cause can warp our commitment or love for other things in such a way that the commitment can no longer be called love. But we also, as humans, live with conflicting loves and with ultimate loves that shape our interactions with all other things — it’s part of being ‘worshippers’ or ‘lovers’ to orient ourselves to the world based on some vision of what is ultimate, and to organise our ‘sacrifice’ (of time and energy and relationships) accordingly; whether it’s career, or success, the improvement of the world for future generations, or the propagation of a culture or religion, there are socially acceptable and unacceptable ways to order our loves and the impact those loves have on others. The effect of our worship on how we treat the people in our lives is a good thing to think through (and a good criteria to figure out the validity of our object of worship using criteria that include things like our emotions). It is good to ask a workaholic (someone who worships work) about the impact that has on their family (and whether they truly love their family, or on what basis they see their work as an act of love or sacrifice for their family). It’s good to consider whether the ‘worship’ or ‘sacrifice’ required in a religious system makes that religious system worthy or good (and even true or reasonable). If a God really is capricious, then worshiping rather than overthrowing that God is preposterous; and if a vision for life in this world requires awful costs imposed on others, then we can ask if it is truly a better alternative.

It’s not that Thanos doesn’t love Gamora, it’s that a greater love allows him to sacrifice Gamora (while grieving over that sacrifice). This isn’t the worst bit of the movie, but part of what makes Thanos such a compelling villain; we understand his motivations, and they are costly and coherent. He genuinely believes that what he is doing — and even the costs imposed on himself, and those who die in his pursuit of the cause — serve a ‘greater good;’ the moral question we have to resolve here (at least to understand whether this sacrifice means he doesn’t actually love Gamora) is more complicated than the Cinema Blend piece allows. We have to ask questions about how moral it can be to co-opt another person for your cause — to play God, rather than virtuous creature — in pursuit of a ‘kingdom of God’ (or gods); and Thanos is certainly depicted as being quite prepared to play god (and slay gods). The minions who buy in to his mission and who carry out the mass killings of people required to secure his vision of the future, are interesting pictures of whole-hearted, unwavering, religious zealotry too.

At least part of the problem we’re faced with in assessing the morality of Thanos’ behaviour is the question of whether his vision is utopian or dystopian (can anybody ever find real peace and happiness knowing the price paid to secure it?), but another part is the question of how much the ‘ends’ ever justifies the ‘means’; and one thing the Cinema Blend piece does well for us is it exposes just how hollow a dispassionate, utilitarian, framework is for us in questions of life, and death, and love.

Basically, what we’re seeing in Avengers: Infinity War is a CGI heavy, cosmic, re-imagining of different versions of the Trolley Problem (and one that allows a sort religious motivation to provide the ‘moral frame’ for making a life or death decision (or acknowleding, perhaps, that the moral frame for such decision making is almost always ‘religious’ in some sense, in that purely rational decision making is utterly unsatisfying to us as humans, and needs to be built on subjective value-based criteria that are more emotional or intuitive than we’re sometimes prepared to acknowledge). If you’re not familiar with the Trolley Problem as an ethical test via imaginary scenario… Here’s how Wikipedia lays it out.

There is a runaway trolley barreling down the railway tracks. Ahead, on the tracks, there are five people tied up and unable to move. The trolley is headed straight for them. You are standing some distance off in the train yard, next to a lever. If you pull this lever, the trolley will switch to a different set of tracks. However, you notice that there is one person tied up on the side track. You have two options:

1. Do nothing, and the trolley kills the five people on the main track.

2. Pull the lever, diverting the trolley onto the side track where it will kill one person.

Which is the most ethical choice?

For Thanos, the problem might be presented this way:

You believe life in this universe is unsustainable and that all people will die terribly if left unchecked. There is a stone that will secure the sustainable life of half the existing population, and life of future generations. Achieving that outcome requires running over the other half of the existing population. You can:

- Do nothing, and everyone dies.

- Claim the stone and kill half of all lives in the universe.

The dilemma, in a utilitarian framework seems fairly straight forward to this point; securing the best outcome for the greatest number means option 2 (for a moment granting the premise that there is literally no other hope or destiny for the people currently alive; no better solution than the death of half of them… the real problem in this movie is a total lack of imaginative alternatives (particularly alternative uses of infinite God-like power from the stones).

The Avengers play out a different ethical system in their initial refusal to intervene to even trade one life for the greater good; there’s tension when Doctor Strange breaks that pact, giving up a stone to Thanos to save Iron Man (though Doctor Strange is no stranger to making sacrifices for the greater good, having died a seemingly infinite number of deaths to save the world from destruction in his solo movie, and he also does this with a sort of ‘infinitely bestowed’ foreknowledge of the paths to the best possible future). This refusal to make trades doesn’t hold forever though; because when it comes to making sacrifices to save half the world’s population from Thanos’ vision, they have their own version of the trolley problem. Vision is alive because of an infinity stone embedded in his head. Thanos wants the stone, and will kill him to take it. Wanda, the Scarlett Witch, has the power to destroy the stone, but she loves Vision and does not want to pull that lever… Their version is:

- Do nothing and half the planet dies.

- Kill Vision, destroy the stone, save half the planet.

The only option on the table at that point, it seems, is option 2.

It’s interesting that both of these dilemmas are built around the idea that to be moral, or ethical, when faced with a scenario like this, is to intervene; the notion that we are the ‘ultimate actors’ in every moment, and that individuals bear a sort of corporate responsibility if they want to be considered ethical or loving.

Thanos faces an even trickier version of the Trolley Dilemma than that first version; on the mountaintop he faces an earlier form of the dilemma… “in which the one person to be sacrificed on the track was the switchman’s child” (wikipedia)… coupled with a version created by controversial moral philosopher Judith Jarvis Thomson:

As before, a trolley is hurtling down a track towards five people. You are on a bridge under which it will pass, and you can stop it by dropping a heavy weight in front of it. As it happens, there is a very fat man next to you – your only way to stop the trolley is to push him over the bridge and onto the track, killing him to save five. Should you proceed?

Thanos faces a scenario where only Gamora’s sacrifice can meet the conditions (in his account of reality) to secure the best possible future for the greatest good, where she is both his beloved child and as a result the person who is ‘weighty enough’ to be sacrificed to secure that future. This version of the trolley problem exposes some of the weight behind the ‘mechanical’ pulling of a lever by making you get your conceptual hands dirty; and this was the price Thanos was willing to pay to secure his religious vision. He was prepared to personally sacrifice his beloved child in order to secure what he believed was good for the world.

I want to suggest that the problem with Thanos; what makes him a villain and his love hollow is not that he sacrificed Gamora, but that his vision was not good; that the killing of half the life in the universe to save the other half is vicious, rather than virtuous, that with the power of God in his hands he had myriad better options if he’d bothered to use his imagination, that he should’ve learned something more about the tragic destruction of his planet through the selfish consumerism of its inhabitants than ‘beings need to die so that other beings can consume’… and that perhaps what he should’ve done, morally speaking, was thrown himself of the cliff to give Gamora, his much more worthy and virtuous daughter, the power of the gauntlet, trusting that she would use that power to create a better world; that it’s clear that in sacrificing her he is just as guilty of the distorting self-love that destroyed his planet, and that this selfishness actually colours his distorted vision of a solution to the problems of the universe.

In doing this I want to suggest a better solution to Thomson’s version of the Trolley Problem, and I want to use the Bible to do it… I want to suggest that one element of Thomson’s “fat man” trolley scenario must always be challenged and re-imagined if we’re to pursue true other-centric virtue; and let’s call that other-centric virtue what it really is… love. It isn’t true that we are at the centre of the universe, and that its problems must be solved by our actions and decision making on behalf of others. Where the problem states “your only way” is to take the life of another, there’s actually a question left hanging… what if I jumped in front of the train instead… What if I’m the heavy weight? And even if I’m not, do I gain more in terms of ‘goodness’ or virtue — am I more moral — if I at least try that form of intervention instead. The intervention where I am not the most important person in the world.

I think this is part of the answer the Bible gives to the trolley problem; or the Thanos and Gamora problem… When Thanos is standing on that mountain top with Gamora there are eery echoes of a thread of stories in the Bible involving the death (or near death) of children for the greater good. Passages that have vexed moral philosophers (the sort of people who like trolley problems) and at a gut level, vexed plenty of us, forever — the stories of Abraham and Isaac, Jepthath and his daughter, and God and his son, Jesus. I’m going to suggest that Thanos is more like the abhorrent Jepthath than Abraham and God — and I’m going to be drawing on this excellent article, ‘The Condemnation of Jepthath,’ by my friend Tamie Davis to make this case. Let’s recap the two Old Testament stories…

Abraham is a pivotal figure in the Old Testament narrative; an archetype of faithful trust in God and someone who makes sacrifices in response to that faith, and according to the visions of the ‘good life’ in this world supplied by God. God speaks, and Abraham listens. God calls him to leave his home and his family, and to set out to a new land; Abraham obeys. God tells Abraham he’s going to be the father of a great nation, and despite his being old and childless, Abraham believes. Abraham’s not blameless; he does some stupid things in the story and tries to take fulfilling God’s promises into his own hands a couple of times (in different ways that are less than commendable), but his faith is held up as exemplary, bumbling though it is, and eventually he and his wife, Sarah, have a son, Isaac. What follows is one of the most disturbing stories in the Bible; but also one that gets used to unpack different moral philosophies within a framework where God exists and cares about life in this world (especially in discussions around a thing called ‘divine command theory’). Here’s what happens:

Some time later God tested Abraham. He said to him, “Abraham!”

“Here I am,” he replied.

Then God said, “Take your son, your only son, whom you love—Isaac—and go to the region of Moriah. Sacrifice him there as a burnt offering on a mountain I will show you.” — Genesis 22:1-2

Like Thanos, who takes Gamora to a mountain top where he is forced to decide if he can give up the child he loves for the cause, Abraham takes Isaac to the mountaintop. He is prepared to go through with the sacrifice — though you get some sense from the ‘whom you love’ that this preparation is not without inner turmoil and conflict. He’s about to carry it out when God stays his hand and provides an alternative sacrifice (to Abraham’s joy, and Isaac’s relief). It’s a strange story; but one thing that is clear (though Cinema Blend might disagree) — Abraham loves Isaac, and that love is what makes what he’s called to do a sacrifice (if he didn’t, it wouldn’t be one). What’s clear is that Abraham trusts God’s vision of the future, and his ability to carry it out, more than he trusts his own vision of things.

What’s a bit trickier is that in the context of the Genesis story, Isaac is already marked out as the ‘child of promise’; God has already says he’ll create a nation through him, so though we’re rightly disturbed by Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice Isaac, there’s more than meets the eye… and it does seem legitimate to read Genesis 22 the way the writer of the New Testament book of Hebrews does when it commends Abraham as an archetype of faithfulness.

“By faith Abraham, when God tested him, offered Isaac as a sacrifice. He who had embraced the promises was about to sacrifice his one and only son, even though God had said to him, “It is through Isaac that your offspring will be reckoned.” Abraham reasoned that God could even raise the dead, and so in a manner of speaking he did receive Isaac back from death.” — Hebrews 11:17-19

What I’ve always wondered though, is given Isaac has been marked out as the future for God’s promises — should Abraham have offered himself in his place (he’s quite happy bargaining with God earlier in the piece when it comes to the future of the citizens of Sodom and Gommorah)… this sort of speculation seems permissible in the light of where the story of the Bible goes in terms of a mountain top sacrifice, and doesn’t necessarily contradict the way Hebrews reads the narrative (especially the phrase ‘one and only son’ that has a particular resonance with the Jesus story).

Jepthath’s story is an even closer parallel with Thanos and Gamora than Abraham’s.

Jepthath is a leader of Israel. He’s a warrior. Where Abraham left his family for another land as an act of faithfulness to God’s promises, Jepthath left his messed up family, he was the son of a warrior and a prostitute, and his brothers drove him away, and gathered a gang of outlaws. Israel pulled him back from living amongst foreign nations to lead them in to battle, and he uses their request to secure himself a place as leader of the kingdom — if he successfully delivers them (Judges 11:9). On the eve of battle he strikes a bargain with God. He makes a vow (a stupid vow).

“If you give the Ammonites into my hands, whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me when I return in triumph from the Ammonites will be the Lord’s, and I will sacrifice it as a burnt offering.”

Then Jephthah went over to fight the Ammonites, and the Lord gave them into his hands. — Judges 11:30-32

Predictably, the first thing (or person) to come out of the door of his house is his only daughter. He then gives her up, and it seems from earlier in the narrative that this isn’t just about keeping his dumb promise, but about not threatening his motivations for signing up for the fight to begin with; power. What also seems clear is that he loves his daughter; but his vow and his vision of the ‘greater good’ drive a particular course of action.

“When Jephthah returned to his home in Mizpah, who should come out to meet him but his daughter, dancing to the sound of timbrels! She was an only child.Except for her he had neither son nor daughter. When he saw her, he tore his clothes and cried, “Oh no, my daughter! You have brought me down and I am devastated. I have made a vow to the Lord that I cannot break.” — Judges 11:34-35

Tamie brings feminist readings of the story into conversation with evangelical readings, and a parallel with the Abraham and Isaac story; she says:

“Maltreatment of women accompanies the fall of the nation; it conveys the terrible extent of the moral decay of Israelite men and society. When it comes to reading the story of Jephthah, then, located in the middle of Judges, we may have room to read the daughter positively but certainly no warrant to view Jephthah as faithful… Unfaithful Jephthah is representative of Israel’s own turn to apostasy; to construe him otherwise would present a sudden upturn in the downward spiral. Such parameters as these are not at odds with feminist concerns. Jephthah’s actions are by no means commendable; the death of his daughter is in no way endorsed. These are part of a loathsome era of Israel’s history.”

When Tamie compares the two stories, to help unpack this reading, she points out thematic links between the narratives (that also apply to the Thanos and Gamora scene, except that Gamora isn’t the only child, Thanos has just been torturing her adopted sister, Gamora is, it seems, the only loved child):

In their narrative contexts, both children are the sole descendants of their parents, the beloved child and the only hope of the continuation of their line. The parent on view in both cases is the father and he is to be the sacrificer (Gen. 22:2, 10; Judges 11:31, 36, 39). In both cases, the sacrifice has a religious character: it is to fulfil an obligation to God, and the child is to be sacrificed to God. Both stories hence play with questions about the duty to protect family coming into conflict with loyalty to God. Which allegiance is stronger? How should the father adjudicate two conflicting moral imperatives?

The difference between Abraham and Jepthath is key to our comparisons here, and helps to position Thanos as a ‘type’ of Jepthath not Abraham. But these two questions about allegiance and competing moral imperatives are the ones that make the Thanos-Gamora scene compelling rather than ‘the worst’… despite our modern, secular, objections to a religious ‘greater good’…

God speaks directly to Abraham, both in promise and in the call to sacrifice. He’s more like a lever in the Jepthath narrative, a being to be used for the purposes of securing Jepthath’s place at the head of Israel, and Israel’s success over their enemies. God doesn’t speak to Jepthath; Jepthath strikes his own bargain, and carries it out without reconsidering (or imagining that maybe when his daughter comes out of the door he should consider that his vow, in itself, was sinful and that there were ways to deal with breaking bad vows in Jewish law). Like Thanos, he commits himself to an unimaginative view of the best possible future for the world — a future where he is at the centre, enthroned. His daughter is a small price to pay to achieve that end; and yet, a large price to pay (what good is it for a man to gain the whole world, and yet forfeit his soul, as Jesus might put it). Jepthath, like Thanos, is a true believer in his place being beside the lever, deciding the fates of all other people.

Tamie also unpacks the inversion of the structure of the two stories (it’s great, read it), suggesting:

“While the backdrop of Genesis 22:1-19 may lead us to expect to see a faithful man and a faithful God, instead, we are left with a God who is sidelined as the unfaithful man treats him like a pagan deity.”

One of the starkest parallels between the stories, at the heart of Tamie’s essay, but also one that is a line to the Thanos story, is that where Abraham is called to sacrifice his son, Jepthath (and Thanos) sacrifice their daughters.

What’s interesting though, is that Jepthath also gets a gig in Hebrews 11, a passing mention, but a mention nonetheless.

“And what more shall I say? I do not have time to tell about Gideon, Barak, Samson and Jephthah, about David and Samuel and the prophets, who through faith conquered kingdoms, administered justice, and gained what was promised” — Hebrews 11:32-33

Somehow, in the awfulness of Jepthath’s actions, and the degeneration of Israel (Samson is also a flawed hero, or an anti-hero, used in God’s plans). God is actually at the lever in these stories — even when the human characters think and live as though they are… even in their unfaithfulness (or the behaviour that specifically puts them at odds with how humans are meant to live under God), God is still at work fulfilling his promises to Abraham, and plans for Israel.

If we were left with just these two stories — Abraham and Jepthath — to assess morality and love, and what you should do with the trolley on the tracks in your own life, then we’d be in a little bit of a pickle. If Abraham’s willingness to ‘pull the lever’ to sacrifice his ‘one son’ on the tracks is our archetype, or if he and Jepthath are totally competing archetypes, we’re left with a pretty arbitrary utilitarianism; the idea that we’re left deciding on the ‘ultimate’ vision for the good life for everyone on our own terms… which inevitably leaves us in the centre of the action, lever in hand (unless we outsource the decision making to others). Abraham’s story centres on a paradox though, which leaves us even more confused — he’s told to kill the child he’s been told is the future, and God has been doing the telling the whole time… He is different to Jepthath (and Thanos) because his vision of the ‘kingdom’ he is sacrificing for isn’t his own kingdom, with him at the centre.

Hebrews actually points us to an interesting ‘final version’ of this story; an archetype to look to in our own trolley problems, and in questions of sacrificing and what is worth sacrificing for… a story that won’t have us sacrificing our children, whether on the altar of our careers, addictions, or visions of a better world, but will have us sacrificing for our children as we live the moral, ethical, and loving life patterned on this story of ‘child sacrifice’.

One of the things that stops God being a moral monster — a Thanos pulling Abraham’s strings — in the Abraham story is the way it is actually used to foreshadow God’s own actions in history — actions the Bible suggests were part of God’s plan before Abraham (Jesus even says at one point ‘before Abraham was, I am’)… another thing, obviously, is that he stays Abraham’s hand and provides an alternative sacrifice to secure his plans (a kingdom built on faithfulness to his word)… first the sheep, and then, Jesus.

If we acknowledge that the Abraham story is internally paradoxical, then the sacrifice of Jesus blows it out of the water in the scale of the paradox. The Trinity, and the relationship between the divinity and humanity of Jesus as God and son of God are complex realities at the heart of the Christian faith… but in the dynamic of the Trinity and the acts of Jesus at the cross we have a father offering up his only son as a sacrifice, but also Jesus offering himself as a sacrifice — the only sacrifice ‘weighty enough’ to stop the train of death and judgment not just destroying five people, but all people. It’s not just a case of God with a lever, redirecting the train to hit Jesus on the tracks, but Jesus, the weighty sacrifice jumping between the train and us, voluntarily and deliberately, both out of love for God and us, and because he trusts the plan — the ‘vision’ of a new reality; he acts from the ‘religious conviction’ that God the father is author of life, and that this sacrifice is not the end of the story to secure a particular future vision, but a step towards resurrection — both for him, and for the ‘greater good’ — the resurrection of as many people as possible in his re-making of the world; his kingdom. Jesus trusts God to pull the lever; and in trusting God to pull the lever, ‘jumps off the cliff to halt the trolley’ himself… what a weird archetypal solution to any formulation of the trolley problem, or the ‘there’s a necessary sacrifice’ problems… to put yourself in the firing line out of love for others, not the self interested belief that you’re at the heart of reality.

In the way father and son combine in the sacrifice of Jesus we’re not just seeing the alternative to Thanos, but the end of Thanos… Thanos is the word for death in Greek, and outside the Marvel Universe, Thanos is the Greek god of death. The sacrifice and resurrection of Jesus represent the defeat of death and the kingdom of death — the spreading of death across the face of the universe; and the replacement of death with life.

There’s obviously not a direct parallel between Thanos and Gamora on the Mountain and Father and Son on ‘Golgotha’ — the ‘place of the skull’ — the hill Jesus was executed on… and yet, there are thematic links (as there are with Isaac and Jepthath’s daughter). Like the differences between Abraham and Jepthath, the differences between God and Jepthath (and God and Thanos) are important ones… Gamora is not a willing participant in Thanos’ plans, she is not Jepthath’s daughter, who submits to her father’s stupidity, she is not Jesus, who willingly entrusted his life (and resurrection) to his father… she has no reason to believe that her father should be entrusted with her life, or that the payoff will be justified.

All these sacrifices share a certain ‘something’ in common; they’re all the life of a loved child being offered up with some sense of the greater good — the trolley problem. But only one of these stories has the child going willingly, and the child being an equal stakeholder in the plan with equal power. After the long line of ‘faithful’ examples, ‘types’ of sacrificers, Hebrews points to the ‘perfecter of faith’ — the actual archetype — Jesus, in his humanity. The example for us when faced with our own trolley problems — all of these stories involve a father who loves their child, but only one of these stories comes with an example that is worth applying in ethical scenarios (real or hypothetical).

Therefore, since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses, let us throw off everything that hinders and the sin that so easily entangles. And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us, fixing our eyes on Jesus, the pioneer and perfecter of faith. For the joy set before him he endured the cross, scorning its shame, and sat down at the right hand of the throne of God. — Hebrews 12:1-2

This is how we know what love is; this is what allows us to take on the burden of suffering, even death, in sacrifice for others… and this is what makes Christianity and its object of worship — our God — better for our kids (and others) than alternatives we might put in its place; any kingdom we might like to build through our own intervention in the world. This is why Christians acting ‘religiously’; with this archetypal story at the centre — eyes fixed on Jesus — are the best thing for the people stuck on the tracks in our world.

This is why the Thanos scene is the best, richest, and most thought provoking scene in the whole movie… because here, the ‘Thanos story’ goes head to head with the ‘Jesus story’…