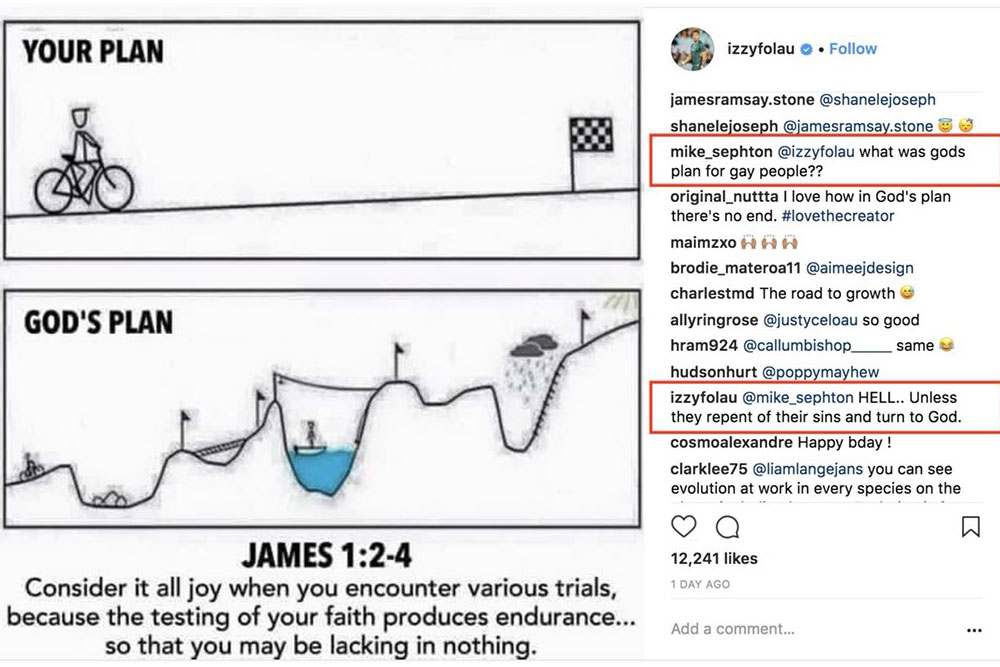

On Saturday I was invited to speak at an event called Gracious Conversations, an initiative of Aboriginal Christian leaders Aunty Jean Phillips and Brooke Prentis, and Common Grace. This is an adaptation of what I said there. I started by inviting people to use their imaginations to write down or capture in some way their vision for a reconciled Australia, and the part we Christians might play in that as individuals and, more importantly, collectively as the church. That’s a worthwhile exercise I think, to try to conjour up some vision of a different Australia to the one we have now — because no matter how good we think it is now we should all have the human faculty — the imagination — that allows us to picture something better.

I’m colour blind.

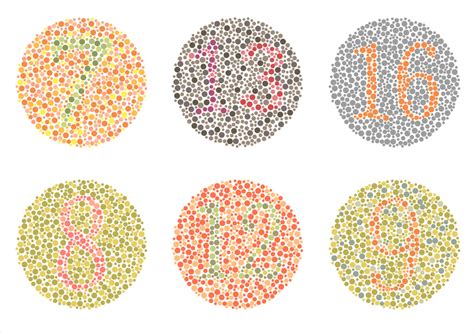

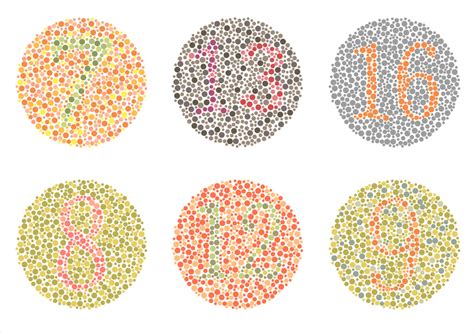

Not in some sort of trendy ‘post-race’ way — but literally… You throw some of these dots up on the screen and ask me to see the number 7… And I’m lost. I can’t even imagine it…

I am also, so far as I can tell, totally ill-equipped to wax lyrical on questions of race and the future of the Australian church; I’m very much a pilgrim on this journey and I’m thankful for wise leaders and co-walkers like Aunty Jean, but to the extent that I am in a position to share anything worthwhile to this conversation, if it is to be a ‘gracious conversation’ I shared some thoughts on my journey out of ‘colourblindness’ on questions of race… suggesting that it isn’t enough, as an individual, to claim ‘not to see colour’ in interpersonal relationships if we want to imagine a better future together…

Have you ever imagined trying to explain the colour red to someone like me? Someone who no matter how hard I strain my eyes is totally unable to see the world the way you do? Here’s how wikipedia describes ‘red’ in its entry:

“Reds range from the brilliant yellow-tinged scarlet and vermillion to bluish-red crimson, and vary in shade from the pale red pink to the dark red burgundy. The red sky at sunset results from Rayleigh scattering, while the red color of the Grand Canyon and other geological features is caused by hematite or red ochre, both forms of iron oxide. Iron oxide also gives the red color to the planet Mars. The red colour of blood comes from protein hemoglobin, while ripe strawberries, red apples and reddish autumn leaves are colored by anthocyanins”

Which is all nice and kinda evocative and poetic — but utterly useless if you can’t see the distinctive features of any of those reference points.

The thing is, when it comes to the colours of reality — the world as it really is — we’re all colour blind.

Meet the mantis shrimp.

“Some species have at least 16 photoreceptor types, which are divided into four classes (their spectral sensitivity is further tuned by colour filters in the retinas), 12 for colour analysis in the different wavelengths (including six which are sensitive to ultraviolet light) and four for analysing polarised light. By comparison, most humans have only four visual pigments, of which three are dedicated to see colour, and human lenses block ultraviolet light. The visual information leaving the retina seems to be processed into numerous parallel data streams leading into the brain, greatly reducing the analytical requirements at higher levels.”

These bad boys and girls see much more of the world than we do — and if we gave them human voices and the ability to describe the world they would expand our horizons a little, even if we couldn’t actually see the reality for ourselves, so long as we trusted the description of their experiences was an accurate rendition of a world beyond our grasp.

I want to confess.. For a while I did believe that when it came to issues of race in Australia — colour blindness was my super power. I grew up in a small town in northern NSW and had plenty of indigenous classmates — friends — even. I’ve always been convinced of the full equality of our first nation’s people. I was so proud of myself that I told myself I don’t see colour… I think this is symptomatic of a view of race issues in Australia that focuses on the responsibility of the individual to not be racist in the we we think of or speak about others; we can tell ourselves ‘I’m not racist because I have aboriginal friends.’

And then I realised that’s a massively limiting decision in terms of what sort of change might be required in our nation — an imagination limiting decision… and a limited view of what is actually wrong with the world when it comes to race — the systemic side of life; and that I’m blind to the experiences of that system. So I had to try to get past this colour blindness; and to some extent that’s the journey I’m still on today.

If we Christians collectively want to free our imaginations and to be able to work for real change in our nation as people with renewed imagination, who are perhaps able to discover something ‘super human’ — we need to be to be more like the mantis and less like colour blind me.

And I have to confess it wasn’t just when it comes to the issue of race in Australia that I feel like I struggled to see something important… It’s this passage from Ephesians as well. I feel like meditating on it over the last few weeks has been eye opening. It’s a prayer from the Apostle Paul as he writes to a church he loves…

Paul writes out a prayer that he prays for them — a rich prayer — there’s some great stuff here when it comes to race, where God is the god of every family… Every nation… Every race… And Paul says he kneels and prays that “out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in their inner beings…”

It’s the sort of prayer that should shape the life of the church…

For this reason I kneel before the Father, from whom every family in heaven and on earth derives its name. I pray that out of his glorious riches he may strengthen you with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith. And I pray that you, being rooted and established in love, may have power, together with all the Lord’s holy people, to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ, and to know this love that surpasses knowledge—that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God.

Now to him who is able to do immeasurably more than all we ask or imagine, according to his power that is at work within us, to him be glory in the church and in Christ Jesus throughout all generations, for ever and ever! Amen. — Ephesians 3:14-21

His prayer is that Jesus may dwell in their hearts — not a small prayer — so that they — and we as we take up this prayer — may first be rooted and established in love — that this church might have power with all of us who are the Lord’s people; power to grasp… To properly imagine… The love of Jesus.

He dwells in our hearts so that we might know how great God’s love is for us…

That’s a bit mind blowing. Right?

And this isn’t just a ‘head knowledge’ thing… Paul wants them — and us — to know the love of God and be filled with the fullness of God. These are big words for Paul; ‘fullness’ comes up a bit in his writing.

The other thing this prayer suggests — that God is able to do immeasurably more than we ask or imagine — is that our imaginations about what is good and possible in this world are always going to be limited; God always imagines more, and in this there’s a challenge for us to be expanding our imaginations to something closer to God’s imagination.

What is it that limits our ability to imagine?

Why is there more possible? How might we expand our imaginations towards something closer to what God hopes to give us in his fullness and according to his power?

Is it possible that our dreams of a reconciled Australia and the part the church might play in it are too small?

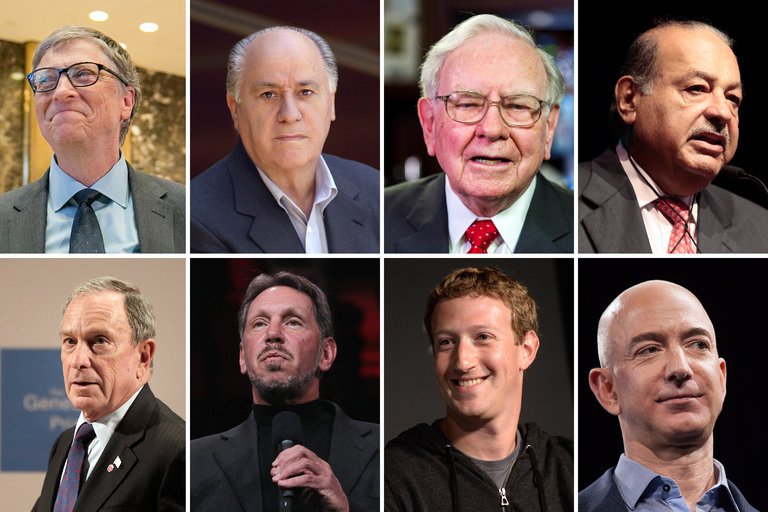

Here’s a few principles from some white blokes that I think diagnose how, ironically, it can’t be white blokes alone who pull us out of this mess.

We can’t know what we don’t perceive

This seems so obvious that it almost doesn’t need saying — and Donald Rumsfeld famously got tripped up trying to explain this once — but a basic aspect of our creaturliness — or our limits — that we exist in a body in time and in space — is that we don’t know everything, but a corollary of this is that we don’t actually know what we don’t know, and we’re especially limited when it comes not just to things that we haven’t seen or experienced or studied yet, but in things that we can’t possibly see or experience…

And what’s extra troubling for us as social creatures is that so many groups or ‘identities’ are formed around things we cannot possibly experience for ourselves…

I can’t, without being told — or without changing the picture — access all the information in the Ishihara tests above. Many of you can.

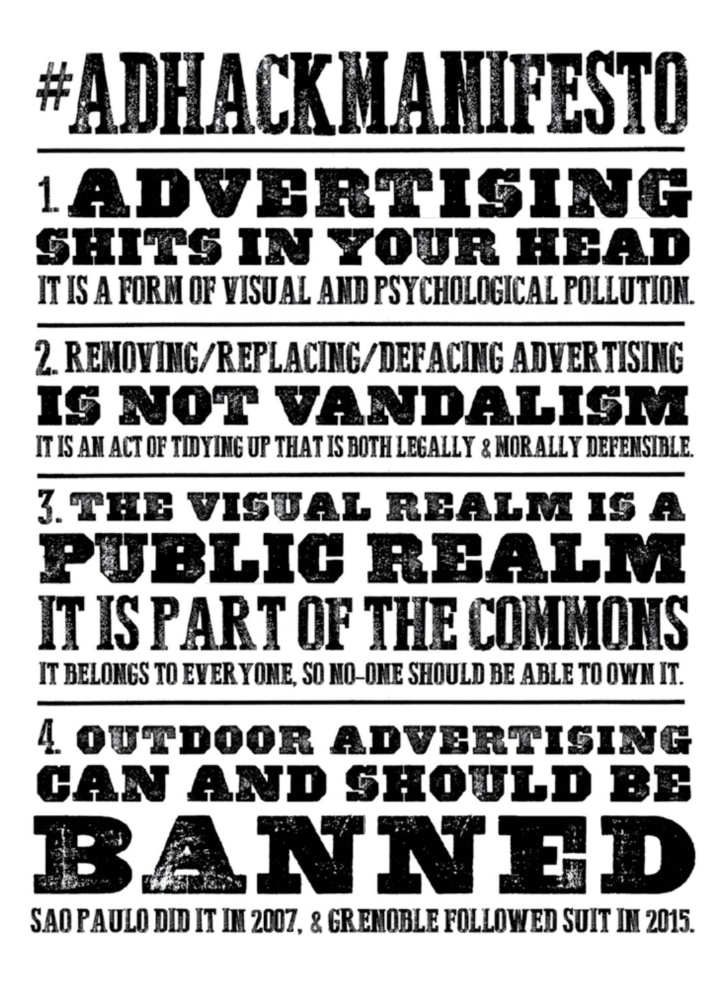

But perhaps the only thing worse than realising your limitations is deliberately choosing to stay limited. Choosing to live as though your perception of reality is reality. Which is what most westerners have adopted as a default way of seeing and being in the world…

Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor wrote this massive book called ‘The Secular Age’ — it’s an account of how the modern western world functions — charting some of the default assumptions that guide society as we experience it… It’s not an all-encompassing theory and there are insights in it that you can take or leave, but perhaps his best thinking is around the way we see ourselves in individual terms…

Taylor talks about the “buffered self” — he says the typical modern individual is, by default, ‘closed off’ from the world; we live in a bubble — we’re now suspicious of the idea that there’s a spiritual reality interacting with our experiences, but we also like to believe we aren’t shaped by causes beyond our own will or control, we’re suspicious of descriptions of the world that involve ‘systems’ at work. This translates into a bunch of practices all of which ultimately serve to limit our perspective on the world and reinforce this buffering.

The opposite to the ‘buffered’ self — closed off from the world — is the ‘porous self’ the self who realises our creaturely limitations and so is open to the idea of a spiritual reality, and open to listening to other ‘selves’ and realising that the world is bigger than we might imagine… The imagination is important for Taylor — he developed this idea of a ‘social imaginary’ — the reality around us that shapes our view of both our selves, and the world…

For Taylor the modern, let’s say typically white western ‘social imaginary’ is what he calls ‘the immanent frame’. He makes the point that the modern, secular, world of buffered selves has evacuated God from the universe — where once people believed in something more like a cosmos where the supernatural and the natural worked in concert, we now, in part because of science and our sense that the world is predictable and machine like, don’t believe in ‘transcendent’ things but what he calls ‘immanent’ things… Basically only our experience and perception of the material world matter; and only these experiences and perceptions shape the way we imagine life as individuals and together…

This is a problem because it cripples our ability to imagine, and makes us less inclinced to listen to other voices. It keeps us in a status quo, bumping and grinding through life like cogs in a machine. This is one place where non-white western voices are important; perhaps particularly indigenous voices in our context, in my conversations with first nations people in recent years — not just Christian ones — there is certainly a different sense of the spiritual reality of life in this world, expressed in some ways through a connection with country and with stories.

Another white guy I like is the American novelist-slash-academic David Foster Wallace. He’s dead now. But he once gave this cracking speech to a bunch of university students urging them to see beyond the default… To escape this immanent frame. He wasn’t a Christian but he had this insight that everybody worships. He talked about our default desires to worship sex, money, and power — immanent or material things — and said when we worship immanent stuff — or worship ourselves — it is destructive to us and others; if we never get beyond these default we never escape a system that has been set up to keep people in the default. He started pushing against this immanent frame, urging people to see more…

“The world will not discourage you from operating on your default-settings, because the world of men and money and power hums along quite nicely on the fuel of fear and contempt and frustration and craving and the worship of self.” — David Foster Wallace

Like Taylor who says the loss of transcendence still haunts us, Wallace said this ‘default’ — and our decisions to ‘worship’ material things leaves us feeling a sense of loss, but not necessarily knowing how to scratch that itch. He describes this constant nagging… gnawing… Sense that something more is true, that we’ve “had and lost some infinite thing” and perhaps that we’re increasingly blinded to that reality.

The problem is that our default western way of seeing the world as individuals limits our imagination. It stops us truly imagining the power and scale of the systems arrayed against change; but also stops us imagining shared solutions to those systemic ‘status-quo’ problems.

C.S Lewis (a third white bloke) wrote about this tendency we have too — about what the default does for us — what the pursuit of pleasure, sex and power does for us in terms of narrowing our ability to enjoy the infinite… He says this stunts our imagination… So that we become like a kid who thinks the best thing on offer is mud pies in a slum when there’s a beach down the road…

“Indeed, if we consider the unblushing promises of reward and the staggering nature of the rewards promised in the Gospels, it would seem that Our Lord finds our desires, not too strong, but too weak. We are half-hearted creatures, fooling about with drink and sex and ambition when infinite joy is offered us, like an ignorant child who wants to go on making mud pies in a slum because he cannot imagine what is meant by the offer of a holiday at the sea. We are far too easily pleased.” — C.S Lewis, The Weight of Glory

Somehow we have to open our eyes — and our imaginations — to see both the problem and the better way forward.

We can’t see beyond our default without expanding our horizons

For people who take Taylor’s Secular Age seriously — the idea of the buffered self and the disenchanted world — the challenge for all of us who want to upend the default system — the patriarchy; the status quo; the way sin permeates this world not just in individuals but in structures… is to see the world differently… To re-connect with other people beyond our ‘buffered’ boundaries of comfort; we’re quite happy hanging out with people who help us maintain this buffering… And we also need to re-enchant the world; rediscover the super-natural, or what Taylor refers to as the transcendent... The idea that God is present and acting in time and space…

The challenge for those of us who follow Jesus is to see living and bringing a taste of the kingdom of Jesus into this world as the path to doing this, and to figure out where we, in our creatureliness and our sin, and our privileged ‘default’ participation in these systems is limiting this change. To do this we have to get outside ourselves somehow — if ourselves are buffered — and we have to keep asking how much our own view of the world is disenchanted or ‘machine like’… We have to expand our horizons — to expand our social imaginary. This is, for example, part of why C.S Lewis in his intro to his translation of Athanasius’ On The Incarnation urged us not just to read modern books but ancient voices as well; but we don’t have to go back in time to find different perspectives.

We have to see that each of us is colour blind by default — we don’t see everything — but also to realise that colour blindness is part of the problem… Not the solution.

Part of this — like my colour blindness — is just creatureliness. We actually don’t know everything because of our particular limits as creatures — we see this in the Mantis Shrimp — who sees more of the world than we do… But we also know that we are finite and God is infinite, but part of the humility of accepting our finitude is acknowledging that other people will see and experience things that we don’t, and that their perspectives are part of accessing bigger truth about the world we live in.

We can’t ‘imagine’ what our mind can’t conceive

To imagine something is essentially to conjure up an image in our mind. The problem with our limited seeing isn’t so much that we don’t experience all there is for ourselves — we can’t experience everything, everywhere, everywhen… The problem with our limited seeing is that it places limits on our shared future because it limits our imagination. If we can’t know what we don’t know, we also can’t picture — or envision — or imagine using these concepts that are beyond our grasp.

If I can never truly see or experience red how can I appropriately paint with it — how can I imagine a world with a different use of red? A richer use of red? A red consistent with or subverting our experience of red…

You can, of course, replace red with any experience foreign to your own.

How can I imagine a world where the experience for our first nations people is vastly different to what it is now — but also consistent with the desires of our first nations people — if those experiences and desires are utterly beyond my comprehension?

How can we repaint or reimagine the world without the full array of colours — or experiences — at our disposal.

Some time ago I discovered Tolkien’s masterful essay On Fairy Stories — it was life-changing for me — not just because the epilogue is a most fantastic description of Jesus and his story that makes my heart sing, but because of its explanation of the relationship between the imagination and creating new worlds.

He talks about this power beginning with our ability to see the world… To describe the world… To use our minds to see ‘Green Grass’ not just as ‘grass’ but as ‘green’ and to take that ‘green’ and do things with it…

“The human mind, endowed with the powers of generalization and abstraction, sees not only green-grass, discriminating it from other things (and finding it fair to look upon), but sees that it is green as well as being grass… The mind that thought of light, heavy, grey, yellow, still, swift, also conceived of magic that would make heavy things light and able to fly, turn grey lead into yellow gold, and the still rock into a swift water. If it could do the one, it could do the other; it inevitably did both. When we can take green from grass, blue from heaven, and red from blood, we have already an enchanter’s power—upon one plane; and the desire to wield that power in the world external to our minds awakes. It does not follow that we shall use that power well upon any plane. We may put a deadly green upon a man’s face and produce a horror; we may make the rare and terrible blue moon to shine; or we may cause woods to spring with silver leaves and rams to wear fleeces of gold, and put hot fire into the belly of the cold worm. But in such “fantasy,” as it is called, new form is made; Faerie begins; Man becomes a sub-creator.” — J.R.R Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

We can take green from grass, and other colours… And use them to make magic… To re-imagine or create worlds in our heads… But also to reimagine the world we see before us… We can imagine our white house painted blue, or green… And make it happen… But we can also do this on a much grander scale…For Tolkien this is part of being made in the image of the imagining God; the God who creates by speaking. By imagining something and then describing it in such a way that it happens. Tolkien is wary of our capacity to create — to use this power well — he uses the creation of fantasy to explore not just opportunities, but the dangers of the human imagination — we can use our power for evil — not escaping the default craving for gaining the things of this world at the expense of others; so we use our imagination to make weapons, or new systems, to paint others as ‘less than us’, to create advantage for ourselves… But what’s going on as we do this — as we use our imagination to create things — is what it means for Tolkien for us to be God’s image bearers — it is for us to be ‘sub creators’ — following the example of God and ‘building worlds’…

But we can’t create — we can’t sub-create — we can’t build worlds — in stories or re-making the real one — without first being able to see and describe this world such that we can re-imagine it differently… My ability to use these powerful adjectives is limited by my vocabulary, or my conception of reality. If we want to bring changes to the world as it is, and have some idea what the real problems are and what real changes might be good… We need more words and more than just the desire to extend our limited status quo to the lives of others… Which is to say, when it comes to questions of race we can’t be colour blind in such a way that we expect the solution to be that everybody just becomes like me. Or like you.

Imagining something totally new requires expanding our vocabulary

If we’re going to imagine a new world we need words and concepts from outside our experience; words that come from new experiences but also from the otherwise inaccessible-to-us experiences of others.

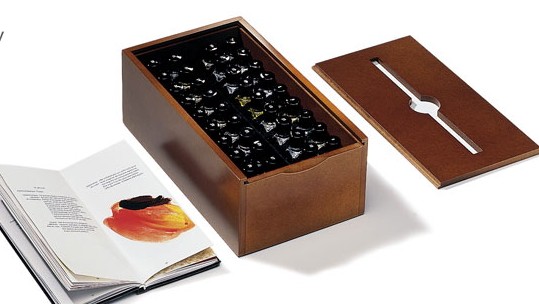

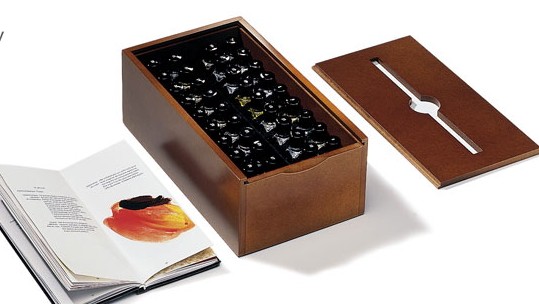

I’m a bit of a coffee nerd… But not to the extent that I’ve forked out the few hundred bucks it costs for one of these… This is a scent kit. It’s designed to help you expand your scent vocabulary so that you can more accurately describe the tastes and smells of coffee — using descriptions like ‘elderflower’ that are going to be meaningless to most coffee drinkers… The idea is that we’re basically ‘scent-blind’ — and unless you have experienced and become familiar with a scent, you won’t be able to describe it… all the labels that get used for the tastes and smells of coffee when you go to your fancy roaster are meaningless unless you have some reference point — unless you have this shared vocabulary…

And maybe our exercise of re-imagining Australia is a bit like this….

Maybe what you wrote down or pictured before is limited by your experience and your sense of the world — or by the people you have spoken to so far… Colour blindness in the ‘I don’t see race…everyone is the same to me’ sense isn’t a solution, it’s a commitment to the status quo never changing — and to never hearing why it should.

It’s an excuse not to listen. An excuse to stay buffered. To deliberately limit your imagination; to not expand your experiential vocabulary and to insist that others should instead talk and see and imagine like you do.

Maybe the equivalent to the scent kit for the coffee taster is the art of gracious conversations for those of us who want to imagine a better future for our world and so work towards creating it together…

The realisation that I mostly just listened to the voices of middle aged, educated, white blokes – as useful as they might be for some stuff – was part of what prompted me not just to read wider but to seek out local voices like Aunty Jean. To start the journey of conversations with her re-imagining what life in our churches and communities might be like. But there’s another voice we should be listening to to blow our horizons out towards the infinite… The transcendent… To help us see reality as it really is…

True imagination begins with seeking the imagination of God

“For we are God’s handiwork, created in Christ Jesus to do good works, which God prepared in advance for us to do.” — Ephesians 2:10

One verse I had noticed in Ephesians before and spent lots of time reflecting on is this one – but here’s something cool – those bolded words – are words that require imagination on God’s part; we are his handiwork because he imagined us in a particular way – we are created in Christ and there’s a particular image the Spirit is working on in his work to transform us, and God has even imagined the work we will do – he has pictured and prepared it in advance…

Our job is to get on board with imagining life according to God’s imagination, not our own…

There is a story in the Bible about our unfettered collective imagination that pays no heed to God’s imagination — an imagination without limits — which shows the danger of us imagining in ways that want to supplant God, in ways where we think we should be God… Where people listen to one another in an echo chamber. The story of the Tower of Babel; a pre-cursor to Babylon, the Bible’s grand image of an earthly city captivated by idols that ultimately captures Israel (whose hearts have long been captivated by ‘material’ idols before that moment); the way out of the corrupt ‘social imaginary’ we create for ourselves by failing to pay attention to God is for him to intervene and to interrupt the ‘material world’ we want to build for ourselves.

The defining pattern we have for keeping our imaginings in step with his is Christ Jesus… who we are re-created ‘in’. When Paul talks about God doing more than we imagine… it’s according to his power at work within us (Ephesians 3:20-21) as these new creations who, by the Spirit and through God answering Paul’s prayer are able to ‘grasp’ or imagine the size and scale of God’s love for us as we’re filled to the measure of the fullness of God (Ephesians 3:19). Fullness is an interesting word in Ephesians – in chapter 1 (Ephesians 1:9-10) it gets translated as ‘fulfilment’, but it’s the same root and somehow ‘the fullness of time’ God’s ultimate plan is this unity or to steal a word from Colossians, reconciliation, of all things in heaven and earth – and it is reconciliation in Christ. The fullness word comes back in Ephesians 1:22-23 with this picture of ‘all things’ being placed under the rule of Jesus, under his feet, with him as the head of his body, the church, the ‘fullness of him who fills everything’… somehow we – the church – the body of Jesus – are where the ‘fullness‘ of God is to be found in this world… we’re a taste of God’s imagined ‘full’ future… Ambassadors of reconciliation as we’re ambassadors of Christ, but ambassadors who are meant to work in the world trying to line up our limited imaginations and ability to see and taste and touch with the infinite imagination… and how can we hope to do that without listening to him and watching him at work in Jesus, but also listening to one another – those he is at work in by his Spirit.

There’s another prayer in Ephesians. Not just the one I hadn’t really paid much attention to…

I pray that the eyes of your heart may be enlightened in order that you may know the hope to which he has called you, the riches of his glorious inheritance in his holy people, and his incomparably great power for us who believe. — Ephesians 1:18-19

The power we have in us to reimagine and change the world – what we’re meant to be able to accomplish when the ‘eyes of our heart’ – our imaginations and desires – are enlightened is hope and this incomparably great power…

“That power is the same as the mighty strength he exerted when he raised Christ from the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly realms, far above all rule and authority, power and dominion, and every name that is invoked, not only in the present age but also in the one to come.” — Ephesians 1:19-21

It’s the power of resurrection… as we seek reconciliation in Christ we’re really carrying the miraculous power of moving people from the kingdom of sin and death and darkness and disenchantment – the status quo – into a kingdom of colour and light and life… We are resurrection people; God’s handiwork, imagining and working towards a resurrected world.

We don’t want to be colour blind…

We want to be cross eyed…

Gracious conversations centred on the death and resurrection of Jesus are the key to re-imagining Australia for the better

What might it look like if we re-imagine Australia not just listening to each other — and so enjoying the fruits of reconciliation that Jesus won for us through the cross; forged by the Spirit… But listening to God and seeing that the source of his power is the death and resurrection of Jesus — the cross — which gives us a new way to imagine solutions to the problems of this world.

It gives us a new way of seeing the world… It’s like seeing more colours… The sight that comes from the Spirit. Gracious conversations mean:

- Acknowledging our limitations… And realising that when we have more colours in the can we can paint something even more vivid and beautiful and real…

- Getting a bigger picture of the world as it really is…

- Listening to others and having their perception of reality shape ours.

- Bringing all our colours and perspectives and experience and insight to a conversation where we are seeking to be gracious to one another – acknowledging our own limits and focusing on listening rather than speaking – so that we might bring God’s grace — the ‘vivid colour’ of God’s imagined future to the world.

That’s what I think Aunty Jean means when she keeps telling me the cross of Jesus is the hope for our country – not just for first nations people, but for all of us.

That’s the vision – the imagination — I think God wants to inspire in us by his Spirit as we dwell on the mystery of Jesus and our glorious inheritance – that we taste the infinite; and have that gnawing sense we all carry satisfied in Jesus; that we have a new status quo — a new ‘social imaginary’ – a new way of seeing the world and a new understanding of our limits in Jesus.

Imagine that.