If you haven’t read my last post, which unpacked a church in a box created by OpenAI’s ChatGPT tool, then, this latest one isn’t going to make a whole lot of sense.

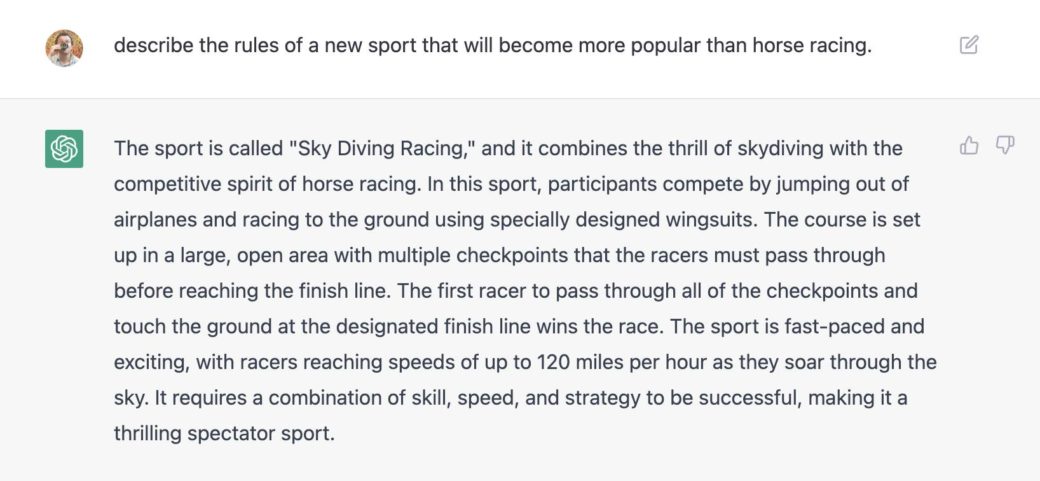

I’m not the only church leader type playing around with this new technology, or demonstrating how it can be used in the life of a church — some people I know are using ChatGPT as a research and writing assistant to streamline some of the more menial and ‘paint by numbers’ aspects of church life. You can, for example, pump out a generic welcome announcement with a conversation starter like this:

Welcome to our church service this week! We are so glad that you have joined us in worship today. After the service, we invite you to stick around for a cup of coffee and some lunch. Not only is this a great opportunity to catch up with friends and meet new people, but it also helps us to build a strong sense of community within our church.

We especially want to extend a warm welcome to any newcomers who are visiting us for the first time. We understand that visiting a new church can be intimidating, but we want to assure you that you will be received with open arms and that we are here to support you in any way we can. If you have any questions or would like to know more about our church, please feel free to speak to one of our members after the service or visit our website. We hope you enjoy the service and look forward to getting to know you better.

And, those mini-sermons that worship leaders (or ‘song leaders’ in Sydney Anglican inspired churches) give before a song — well, ChatGPT’s got your piety covered as well, here’s an intro to the song Shout to the Lord.

“It’s time to lift our voices high And sing out to the Lord With all our hearts and all our might We have come here to worship And give our King the praise He deserves So, put your hands together, And let’s sing out loud The song of victory, the song of salvation The song that reminds us of the power of our God It’s time to Shout to the Lord! This song is a powerful reminder of the love and grace of our Lord and savior, let’s sing it with all our hearts and give him all the glory, honour and praise he deserves. Let’s sing it together, Shout to the Lord!”

You know you’ve heard that song intro before. And that’s kinda the point.

Now, the other thing I was thinking, was “who better to predict the future of the church than the technology so many church folks (and tech futurist types) are seeing as part of the future?”

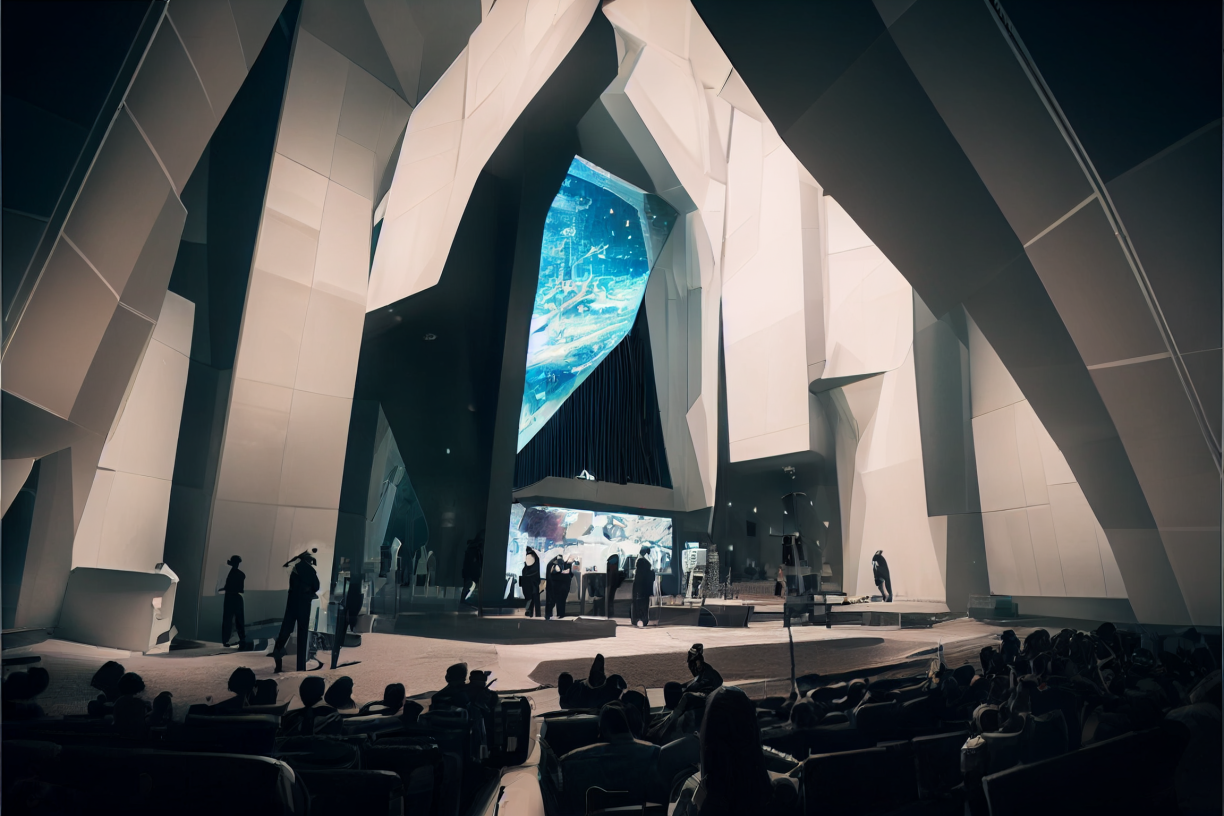

So I asked ChatGPT to predict (and even suggest) ways that churches could incorporate emerging technologies like machine learning, virtual reality, and interactive glass surfaces into their rhythms and spaces. And here’s what the machine suggests.

Some examples of emerging technologies that could potentially be used in a church setting in the future include:

- Artificial intelligence: This could be used to create personalized recommendations for biblical studies or spiritual growth, or to provide answers to frequently asked questions.

- Virtual and augmented reality: These technologies could be used to create immersive experiences for worship, Bible study, or other events. For example, a church could use virtual reality to take members on a virtual tour of biblical sites, or to create a simulated gathering space for virtual services.

- Blockchain: This technology could be used to securely track donations, manage membership records, or facilitate online transactions.

- 3D printing: This could be used to create physical copies of biblical artifacts or other objects for use in worship or educational settings.

Here are a few ideas for integrating traditional rituals, spiritual disciplines, and practices with new and emerging technologies:

- create personalized devotional materials, such as daily emails or notifications with Bible verses or prayers that are tailored to an individual’s specific needs or interests.

- create personalized spiritual growth plans or tracks, which could include resources such as Bible readings, prayers, and other spiritual practices that are tailored to an individual’s specific goals and needs.

- Using virtual or augmented reality to create immersive experiences for sacraments, such as baptism or communion. For example, a church could create a virtual reality experience that allows members to participate in a simulated baptism ceremony.

- facilitate online retreats or spiritual retreats that incorporate both virtual and in-person elements. This could allow members to participate in retreats from the comfort of their own homes, while still being able to connect with others and engage in spiritual practices.

- create interactive prayer or meditation spaces, such as virtual prayer walls or chat rooms where members can share their prayers and connect with others in real-time.

- create virtual reality experiences that allow members to visit and learn about historical or biblical sites, such as the Holy Land or ancient churches.

- Using virtual or augmented reality to create immersive worship experiences, such as virtual reality simulations of ancient worship practices or events from the Bible.

- facilitate online or virtual services, such as by live-streaming services or offering virtual worship experiences that can be accessed remotely.

- create interactive resources for worship, such as online quizzes or assessments that help individuals reflect on the themes of a service or identify areas for spiritual growth.

- facilitate online prayer or meditation groups, such as through social media or messaging apps, which could allow individuals to connect with others and share their prayers in real-time.

Lots of these aren’t rocket science — there’re plenty of suggestions here that churches have embraced already, even before the pandemic — and some (blockchain anyone) that I can’t see churches embracing any time soon — but, having worked in a church that sent a media team to sites from the New Testament, it seems a small jump from that to creating VR experiences. Some of the more far-fetched stuff isn’t, when you’ve been part of a church community with a million dollar budget and a need to ‘produce’ content or measurable outputs to justify that giving. I’ll write more about this vision of the church in a future post, but for now, let’s consider what happens if we embrace the machine — and machine-like predictability in the way we speak about, and experience, church.

Predictably predictable… like a machine

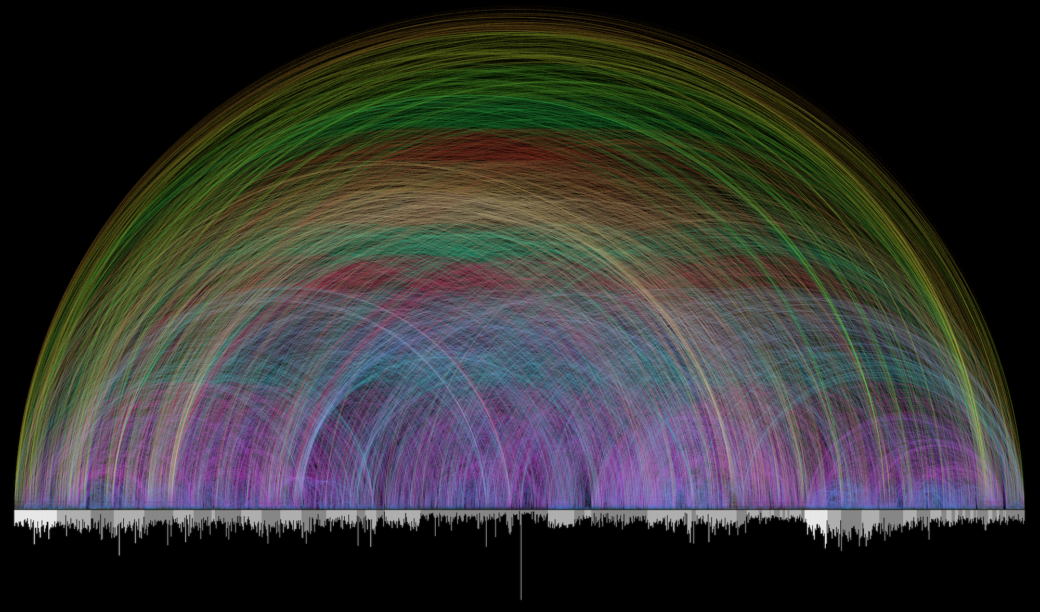

ChatGPT is super brilliant, but it’s also — as a function of its technology — exceptionally derivative. One way to sum up what this technology does is to think of it as a prediction model that, given any given word in a sentence, will try — based on all the words its scanned and all the relationships it has mapped out between words — to match the next word in a sentence with the most predictable sausage.

Sausage obviously isn’t the word that naturally goes there — that’s just something I’ve put in so you know a bot hasn’t written this post. See, ChatGPT describes the way it works this way:

Me: Finish this sentence: ChatGPT’s language prediction model works by…

GPT: using a neural network architecture called a transformer, which is trained on a large dataset of text, to generate responses based on the input it receives. The model uses patterns and relationships it has learned from the training data to make predictions about what words or phrases are likely to come next in a given context. Additionally, the model has been fine-tuned to understand the specific language and conventions of the domain it is being used in, such as conversation, literature, or code.

ChatGPT is a prediction machine, it has built a pretty comprehensive pattern of how words are used in order to guess (rather than understand) the best relationship between certain words in a given category or genre. This means that rather than being a magic wand, that is totally generating new and beautiful art — what Tolkien called “sub-creation,” the magic of elves, this tool ends up being more like a tool someone in Mordor might come up with. It’s derivative, and built from extracting value from existing material. In On Fairy Stories, Tolkien writes about the human capacity to create new worlds with words — once we can imagine a green sun, or mix any unpredictable adjective with a predictable noun — all GPT does, even if you ask for something unpredictable, even if you try to play the game the way I do, trying to come up with novel uses for the platform — like a kids book about a ninja duck with nun-chucks named Quacker-Whacker, whose brother Waddle-Twaddle reads Kafka and helps him break a cycle of violence with a cat named Scratch, propped up by an oppressive bureaucratic system of swans, all the model does is built on predictions based on past behaviours. The real capacity for creativity with ChatGPT lies in the creativity of the human managing the inputs, mashing up predictable outcomes in unpredictable ways, rather than in the machine.

Tolkien believed our ability to sub-create was a function of being made in the image of a God who makes; ChatGPT is a machine that at best replicates images made by images of God, and at worst, amplifies the parts of our creativity and our expression that have become commonplace enough to be predictable. In a letter he writes to a potential publisher in 1951, Tolkien makes a distinction between ‘magic’, in his stories — which was meant to evoke ‘the machine’ in our minds — the sort of will to power on display in Mordor — and the artful, generative, creativity of the elves and Gandalf. He defines this will to power as a desire to “make the will more effective,” and so much of the hype I’ve heard (and felt) about machine learning technologies is around the area of improved efficacy. For Tolkien, the elves use of magic is different to the way fallen (and mortal) humans pursue power; the elves are there to demonstrate something different. He says some things, of the elves, that I think are profound when we apply them to this new technology:

Their ‘magic’ is Art, delivered from many of its human limitations: more effortless, more quick, more complete (product, and vision in unflawed correspondence). And its object is Art not Power, sub-creation not domination and tyrannous re-forming of Creation. The ‘Elves’ are ‘immortal’, at least as far as this world goes: and hence are concerned rather with the griefs and burdens of deathlessness in time and change, than with death. The Enemy in successive forms is always ‘naturally’ concerned with sheer Domination, and so the Lord of magic and machines; but the problem : that this frightful evil can and does arise from an apparently good root, the desire to benefit the world and others.”

Nobody is making machine learning technologies — and pursuing efficiencies through this technology — with a profound desire to cause harm. It’ll be interesting to see what harm is unleashed in the name of benefiting others, and who exactly the “others” are… who can forget Google’s “don’t be evil” mission statement back before the days of surveillance capitalism, and SEO witchcraft, and algorithmic power being wielded in pursuit of profits; tech commentator Cory Doctorow wrote a fascinating article this week about a dynamic he calls enshitification that’s embedded in the rise and fall cycle of big tech products that’s worth reflecting on here, a shift from ‘user focus’ to ‘delivering for shareholders’ that every platform goes through).

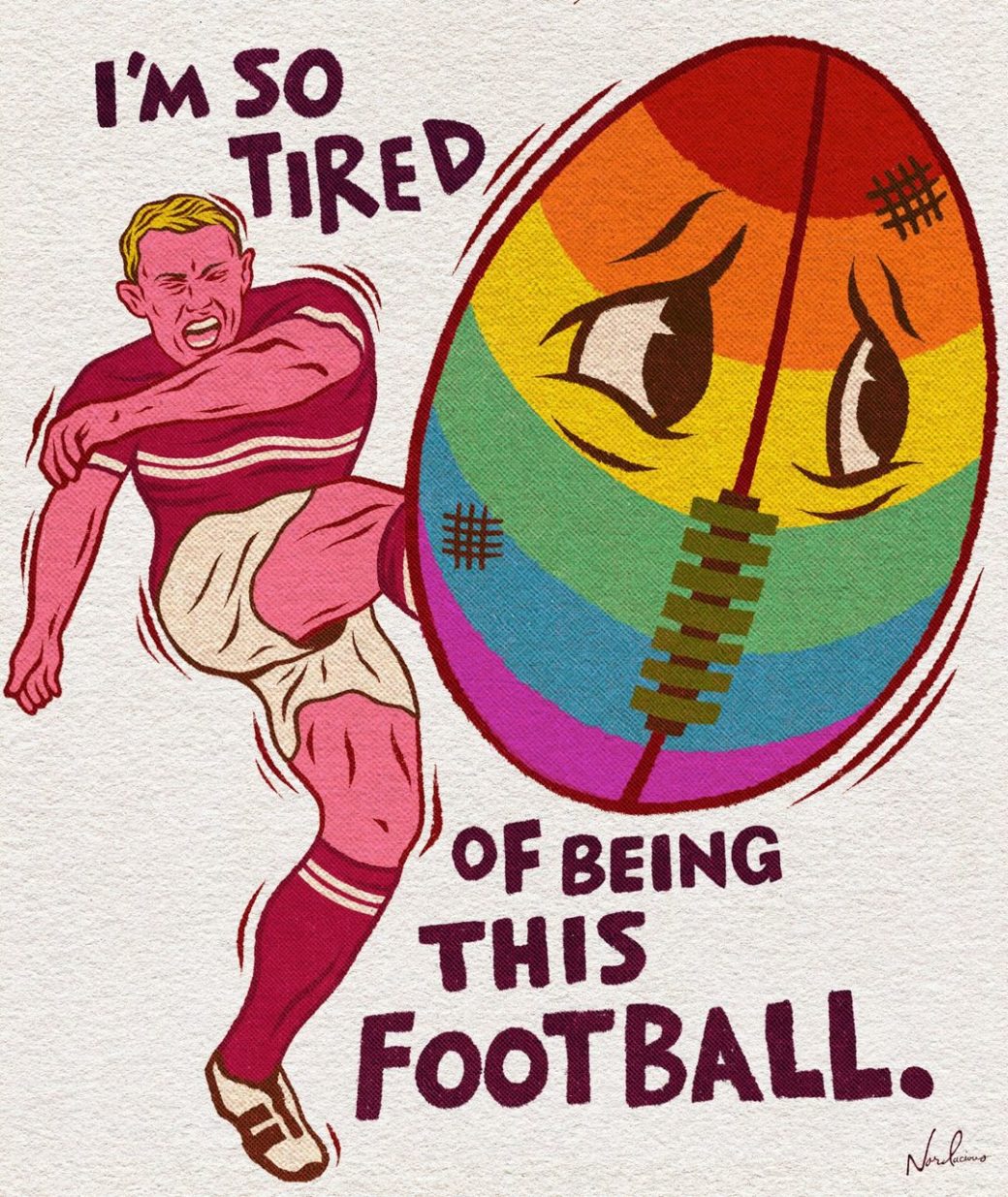

It’s also interesting that Tolkien sees the elves being able to produce ‘art’ rather than mechanical-dominion-magic because they’re both unfallen and immortal — not caught up in trying to grab as much as they can in the little time they have in order to hold suffering at bay. It does raise the question of whether fallen, mortal, humans can create art — or if we’re doomed to make disenchanting dominion-machines of destruction. Because Tolkien would love this so much (by which I mean, he’d hate absolutely everything about it, the image accompanying this post is Ian McKellen as Gandalf interacting with an enchanted touch screen).

I wonder if Nick Cave’s essay about ChatGPT’s songwriting capacity gives us a path towards art-creation built from human limits. Nick Cave described a song ChatGPT wrote “in the style of Nick Cave” as “the fire of hell in his eyes” — this extended quote from Cave suggests that maybe our capacity for enchantment is born from facing our limits; and our mortality (and our suffering) rather than trying to deny them by grasping and destroying, or embracing something mechanical.

Songs arise out of suffering, by which I mean they are predicated upon the complex, internal human struggle of creation and, well, as far as I know, algorithms don’t feel. Data doesn’t suffer. ChatGPT has no inner being, it has been nowhere, it has endured nothing, it has not had the audacity to reach beyond its limitations, and hence it doesn’t have the capacity for a shared transcendent experience, as it has no limitations from which to transcend. ChatGPT’s melancholy role is that it is destined to imitate and can never have an authentic human experience, no matter how devalued and inconsequential the human experience may in time become.

What makes a great song great is not its close resemblance to a recognizable work. Writing a good song is not mimicry, or replication, or pastiche, it is the opposite. It is an act of self-murder that destroys all one has strived to produce in the past. It is those dangerous, heart-stopping departures that catapult the artist beyond the limits of what he or she recognises as their known self. This is part of the authentic creative struggle that precedes the invention of a unique lyric of actual value; it is the breathless confrontation with one’s vulnerability, one’s perilousness, one’s smallness, pitted against a sense of sudden shocking discovery; it is the redemptive artistic act that stirs the heart of the listener, where the listener recognizes in the inner workings of the song their own blood, their own struggle, their own suffering. This is what we humble humans can offer, that AI can only mimic, the transcendent journey of the artist that forever grapples with his or her own shortcomings. This is where human genius resides, deeply embedded within, yet reaching beyond, those limitations.

Just note that last bit — we humans can offer the “transcendent journey of the artist that forever grapples with his or her own shortcomings,” while the machine can only mimic. Machines have no body; no experience of suffering — or of longing — no vision of the transcendent, they are creations within what the philosopher Charles Taylor calls “the immanent frame” — and so they are disenchantment engines. They don’t throw us towards the transcendent, but ground us in predictions about the immanent. It’s interesting, I think, that the paradox at the heart of the Gospel — the transcendent and immortal God who becomes human in order to suffer and die — plays in this magical and enchanting tension in ways both Cave and Tolkien find compelling.

I think it’s fair to say that mechanical ‘church in a box’ techniques that employ machine-like magic — technological artificers — are disenchanting, rather than magical in either an Elvish way or a ‘stare suffering in the face’ way. I’m not sure either the Elves, or Nick Cave, would write about a “vibrant church community” the way our church promotion machine seems to want us to, or the myriad other cliches we employ chasing some sort of magical spell or silver bullet that will grow our churches as someone reads our websites.

A magic mirror held up to our ‘vibrant’ communities

Here’s my thesis about a prediction engine that produces text that has that machine-like feel, that feels quite similar to the sort of text that humans writing to predictable cultural scripts might produce… we’ve already embraced the machine. Long before ChatGPT.

ChatGPT serves as a mirror; its predictive capacity reveals our machine like predictability. Its soullessness, its lack of originality and enchantment is matched by our own.

That Radiance Church could be so profoundly unboxed by ChatGPT in ways that feel plausible says something about the church marketing machine that produces pablum and calls it ‘copy’. Here’s a little exercise. Google the name of your city or town, the word church, and the word vibrant. How many results come up?

Did you catch the description ChatGPT adopted of the church growth consultant it imitated for me in producing Radiance Church — ““My focus is on practical and effective strategies for building and growing a church community that is well equipped to thrive in a modern world. I will emphasize the importance of technology and innovation in building a vibrant and relevant church community that is able to connect with people in the community,” or in the vision statement “To be a vibrant and growing community of believers…” or in the description of the sort of hero image that should be used as a hero image online “a beautiful, vibrant, and dynamic image that captures the essence of the church’s mission and vision,” or the description of Radiance Church it developed for the home page: “Welcome to Radiance Church! We are a vibrant and growing community of believers, passionate about sharing the love and hope of Jesus Christ with all people. Our mission is to glorify God by shining the light of Jesus Christ in our hearts and sharing it with the world through worship, fellowship, and service.“

What does vibrant even mean to someone who has never been to church? For churchy types it’s maybe code for “we have some people under the age of 80” (some of the most vibrant Christians I know are aged 80+ though). It’s such a predictable cliche — it’s so predictable a machine can predict and reproduce it. Some predictability is ok though — right — some of what ChatGPT does offer is the ability to drum out predictable stuff that we’d just be reproducing week on week anyway (or generating content that follows particular established forms, including code). But cliches can also be dead and disenchanting and robotic where we could be working for something more human; imbued with the “human genius,” displayed in “the transcendent journey of the artist” grappling with suffering and existence in a body, shot through with aches and longings for something other than what is, and what has been, utterly predictable.

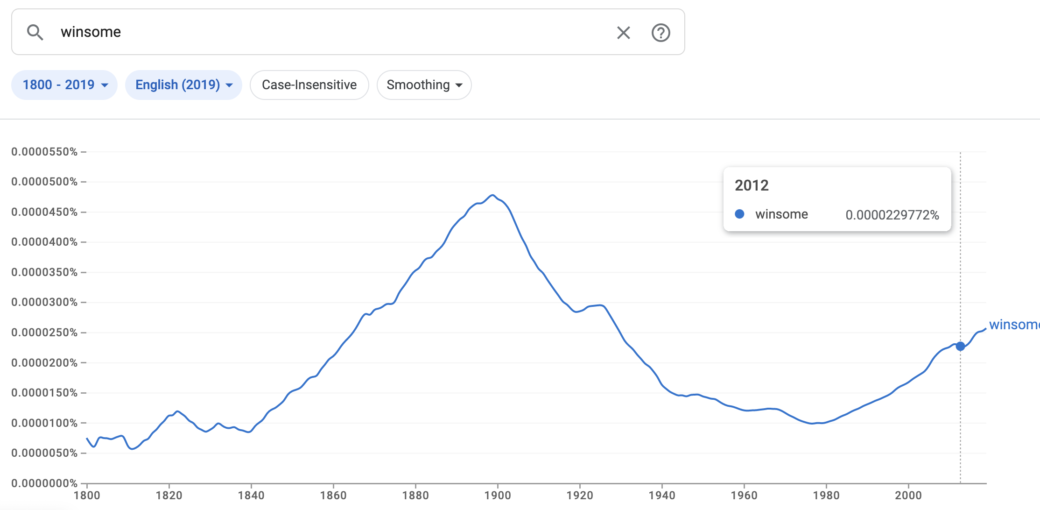

The word cliche comes from the world of typeset printing — from the printing press — its French, the English word with the same meaning is “stereotype” — it described a word or phrase so commonly used by printers that instead of the word being formed letter by letter it’d be stuck together on a metal plate; the same would happen for mass produced documents where you’d make an entire mould to reproduce a whole page on demand. ChatGPT is a cliche producer — it predicts what it has been fed — and so Radiance Church is not ‘the apocalypse’ in the way we might think, we’re not staring into the fire of hell in some distant (or not as distant as we’d like) future; Radiance Church is an apocalypse because it reveals something about how the machine-Church already exists. And how it already disenchants.

ChatGPT’s Radiance Church in a box holds a bit of a mirror up to how we present ourselves — and the sort of repeated grunt-work we’ve brought into the life of the modern church that doesn’t offer the enchantment of embodied liturgies directing us towards heaven — the ‘stay with us for coffee’ benediction, and the ‘welcome to our vibrant community’ call to worship, or the pietistic and cliched one size fits all song intros (and perhaps sermons).

And I guess the question isn’t “is it a magic mirror,” so much as “are we Snow White, or the wicked witch?” Are we actually beautiful and without guile, or relying on deceitful enchantments to prop up our areas of lack?

Could a person reading your church’s website tell it was written by a human? Does it function as art, or part of the machine? And what about our communities — and our approach to life together?

Have we so embraced technology, and technique, and repetition of cliches that we’ve become machine-like and disenchanting — like robots writing Nick Cave songs — or are we using our creative capacity to generate art — or an art-like approach to our language and imagery — that is true and beautiful, that is grounded in our suffering, our mortality, and our desire for transcendence (and that desire being answered in Jesus) so that we present our life together built on the Gospel as something that speaks to these experiences, and our longings for something other than just “vibrant community”.