Men and women are, on average, or typically, physiologically, anatomically, and hormonally different. To deny this is would be odd because the evidence is pretty concrete. Here’s a thing from the Australian Bureau of Statistics from 2011/12:

The average Australian man (18 years and over) was 175.6 cm tall and weighed 85.9 kg. The average Australian woman was 161.8 cm tall and weighed 71.1 kg.

This size and weight ratio, on average, means men are physically bigger and stronger. There are exceptions. But this average also means that men who throw their weight around are a danger to women, and we know this and talk about this beyond the church when we talk about violence against women, rape culture, and the patriarchy. Some approaches to gender issues want to deny or minimise this difference and the effect it has on the world assuming that equality or equity is the answer to this problem.

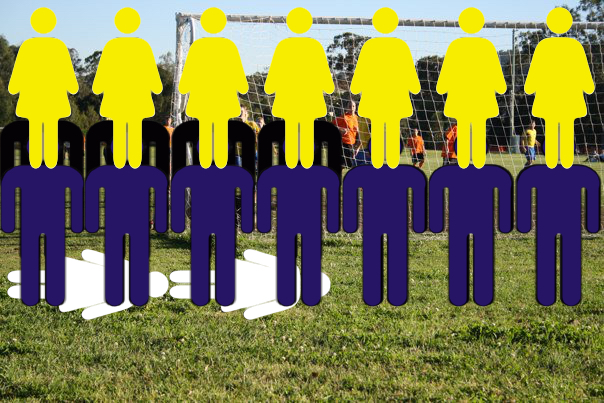

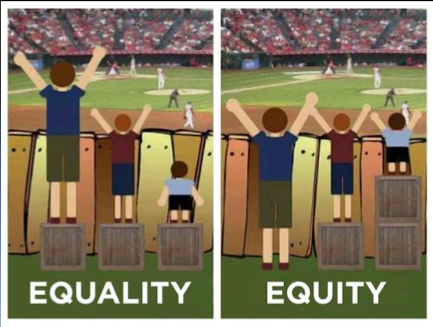

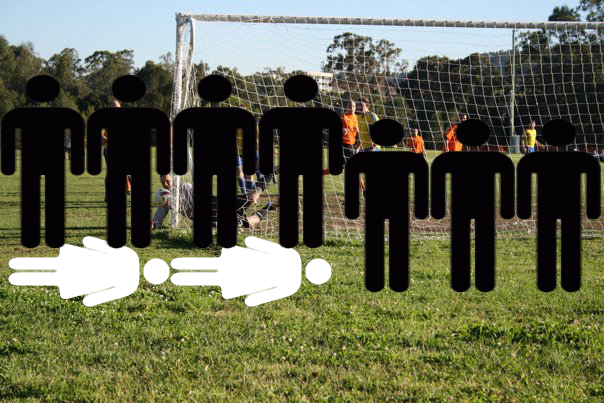

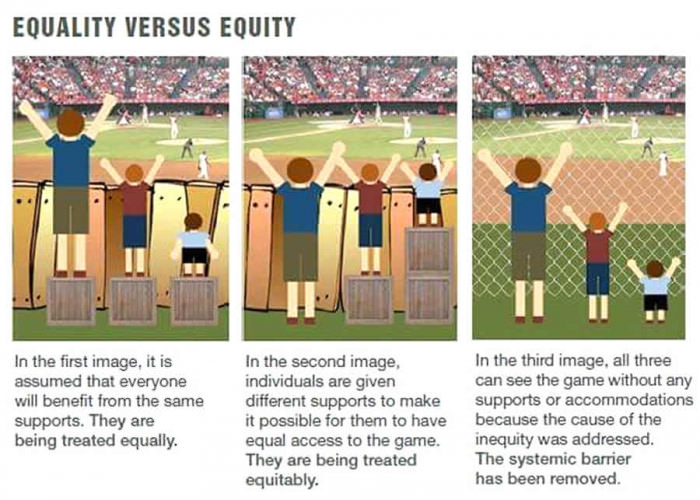

You might have seen this graphic.

Now. I like the sentiment there. But this other version an important corrective; acknowledging that sometimes inequality is a result of systemic injustice.

At the moment Aussie Christians are talking about gender equality in the church and home. And I thought of these pictures and wondered how applicable they might be. I reckon both of these graphics are a bit naive when it comes to problems of gender inequality and the solutions both in the church, and in the world.

Let me demonstrate this graphically with my own little picture. In the interests of using images that I own the rights to, let’s assume that the ultimate good, or what it means for humans to flourish, is represented by the ability to watch my old soccer team, Kustard FC, compete in a grand final (in an equal world this would be a mixed sport perhaps, but bear with me), so the ultimate expression of ‘gender equality’ is everybody enjoying the same view of the game.

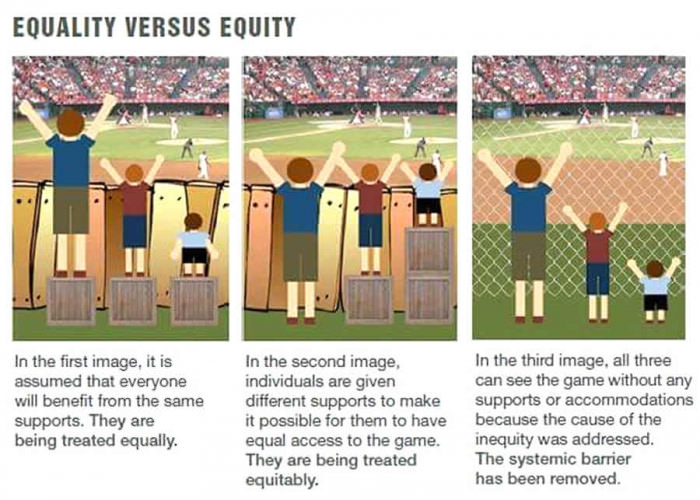

An unimpeded view of the looks like this. No fences. Right behind the goal mouth.

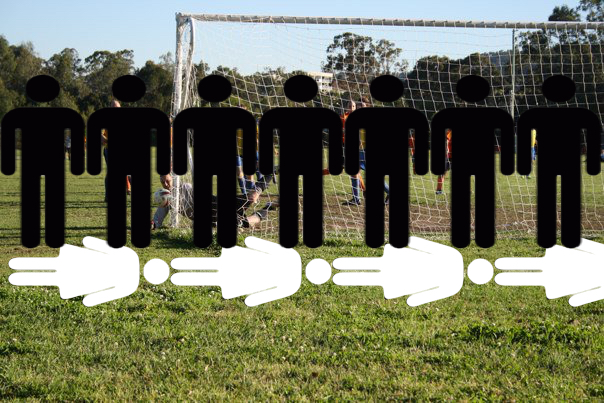

When we talk about gender equality in the church and the world it’s worth acknowledging what we’ve said up front; the different physical strength of men and women, and a few other issues, means that over time men wielding influence and power has become systematised. There’s no fence in this picture; there’s people. Men. This is the patriarchy. A group of 175.6 pixel high, 85.9 pixel wide men using their size and weight to secure their own ultimate good at the expense of others.

Now. This is where it gets interesting for Christians.

Because we have a different sense about what the world should be to our patriarchy loving or patriarchy hating neighbours, that comes from our story, and an explanation for why, instead, the world is the way it is. It starts in the beginning.

Creation.

So God created mankind in his own image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.” — Genesis 1:27-28

I’ve bolded them to emphasise that this is plural and the plurality in sight is ‘male and female’ people as created by God. They are blessed; not cursed. This blessing is caught up in, and enables their partnership. We Christians believe that at creation men and women were created to flourish together in partnership. To share in the task of bearing God’s image, ruling the world together, cultivating and keeping the sanctuary of God’s garden-temple and expanding it as we multiplied his image-bearing presence across the face of the earth. In Genesis 2 we see Eve, woman, created as a helper for Adam, man, because he can’t do his job alone, and the Hebrew word used for ‘helper’ ezer is elsewhere used of God in a military context coming to the aid of Israel, and means something more like ‘necessary ally’ than ‘servant’.

It was meant to look like…

Curse

But things broke. The ideal was lost in the fall (Genesis 3), amidst a bunch of curses (not blessings) in response to Adam and Eve’s sin (and the Serpent’s deception), God says:

“I will make your pains in childbearing very severe;

with painful labor you will give birth to children.

Your desire will be for your husband,

and he will rule over you.” — Genesis 3:16

We were made to rule together, but now, and this is the pattern of life in the world in the Bible’s account of our humanity, man rules over woman. Over, not with.

So now, as a result. Here’s what happens when the average woman (161.8 pixels by 71 pixels) would also like to ‘watch the game’ ie flourish.

The ‘patriarchy’, or the problem of gender equality isn’t a problem where there’s just a fence impeding the view of the women; it’s a problem where men are impeding that view because they are bigger and stronger and it’s to their advantage. The worst form of this probably should be depicted with men trampling all over women because of their strength, not just blocking access to the ultimate good, but abusing women to secure something bad and treating it as good (eg abuse).

This ‘patriarchy’ is not what life was meant to look like; it’s not how men and women were made to live together. This is ‘curse’, as Genesis 3 puts it. This is the new ‘natural’ order of things. It is not good. It is not what God made life to be. It is not the ideal. We might think that because it is normal the best thing to do is to find other things for the women standing behind these men to do. Perhaps they could help them flourish and enjoy the game by giving them a back massage. Perhaps they could play a ‘different’ role, or find a ‘different’ sort of flourishing in order to let men rule. This feels a lot like having the curse be our norm.

So we’re left with three options to respond to this as humans, and as Christians, to deal with this patriarchy. Classically as Christians we see two options, the middle two. We reject the first (rightly), and I want to suggest we should embrace the fourth as we follow the example of Jesus.

Option 1: Embrace it (Chauvinism)

So when men like the four blokes on the right decide that they aren’t just going to secure a better ‘flourishing’ life for themselves by nature of being themselves and benefiting from the system, but rather they’ll use their strength to take advantage of others, trampling on them to secure an even better ‘view’… This is chauvinism. It’s abuse. It’s not just curse it’s sin.

The Changed Status Quo (Curse + Sin)

When sin happens on top of curse we get an even more messed up view of the world. When people take advantage of a power inequality for their own ends it amplifies the problems of a systemic inequality (a broken system). The world now looks like this. Part sinful abuse, part cursed system. Not what it was meant to be.

Christian Options

Now. Let’s for the sake of graphical clarity make Christian men and women colourful, and assume the status quo in the cursed world is part cursed system (patriarchy) and part abusive (chauvinism), that our challenge as Christians is to avoid sinful abuse (chauvinism) and overcome the curse (patriarchy) while living in this world.

Option 2. The Egalitarian Option (full equality)

Egalitarians stress the equality of all people; men and women; and our shared task in the world as God’s image bearing people. It is idealistic in that it looks back to the world before the fall, and the world as promised beyond the fallen world (the new creation) to establish an ideal for how men and women should relate.

Here’s how an egalitarian approach plays out with the status quo in place. And yes. It’s getting confusing. But let me explain what is happening. This is a set of coloured characters we’ll call ‘the church’ operating as equals, overlaid (in the main) over the status quo.

On the left you’ve a Christian man and woman operating where both the their access to a ‘flourishing’ life is blocked by a some abusers who have elevated themselves at the expense of others. The next four people are Christian men and women operating as equals in an unequal society, it’s easy for the man. He just has to be himself, and he gets to flourish without it costing him anything (he can see the game). The women notice no change, they just aren’t being abused; the patriarchy is still in their way. The last two men and women don’t have the patriarchy in front of them because those members of the patriarchy represent that proportion of the population who recognise the inequality and so have become egalitarians… it’s only when the systemic stuff is removed that that last woman on the right has access to the ‘flourishing’ life. It only works for the very privileged (particularly for middle to upper class western white women). It does offer an answer to the unprivileged, but because the diagnosis and the treatment are disconnected from (at least what the Bible describes as) the disease, it’s not totally effective in the face of the patriarchy. It relies, basically, on powerful people either being overthrown, or voluntarily giving up their power when confronted with it. This is why egalitarianism fails; in fact, it’s why I don’t think the Bible puts forward egalitarianism as a solution to the status quo.

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As I’ve argued recently, the antidote to inequality is not equality, equality is a middle ground, a neutral, the positive antidote to inequality is service. A neutral option in a broken status quo won’t cut it (though it’s better than perpetuating or amplifying that brokenness).

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As I’ve argued recently, the antidote to inequality is not equality, equality is a middle ground, a neutral, the positive antidote to inequality is service. A neutral option in a broken status quo won’t cut it (though it’s better than perpetuating or amplifying that brokenness).

Option 3. The Complementarian Option (equal but different)

Here’s one way Christians have approached the relationship between men and women in this world. Charitably it assumes that men and women are different (including physiologically) for a reason, and this difference manifests itself in different roles that do not negate our equality; and that somehow, as we operate as church and family in a fallen world, it makes sense for the stronger man to lead and the woman to help and support men in their work in the home or the church. This assumes that the best way to fight against patriarchy, abuse, or the broken status quo is to team up in a way that relies on strong leadership that challenges the status quo. Uncharitably, and sometimes in practice it assumes that the pattern of the curse is normal.

When it comes to the graph below, where the Christian men and women are in colour, it assumes that if you make a man a Christian it’s good to stand behind him and support him. That the man has a particular role to play in life in the world, as a Christian, and that the woman has a different role, reclaiming the task of ‘helper,’ only, the task looks perhaps different to the way it looked before the fall. Perhaps this difference is because the world is different, and a greater threat to the flourishing of women — but it’s possible that sometimes a Christian bloke is just as likely to get in the way of a woman’s flourishing as a non-Christian bloke.

So. Graphically, the way this plays out is that a complementarian man probably stands between a woman and an abuser (a bit like Jesus standing between the pharisees and the adulterous woman they wanted to stone), so that’s what’s going on with the the first two figures. But, in the next two figures, there’s some reasonable evidence to suggest that complementarian theology can misfire so that men are either abusive without realising it, or claim to be Christians in order to abuse women with some sort of divine support; this isn’t what is at the heart of ‘complementarian’ theology, but many Christian women escaping domestic violence say they were kept there by a theology much like it. In the next (the fifth) little vignette along, we see a complementarian woman standing behind a non-Christian patriarchal husband in order that by her way of life she might save him (eg 1 Peter), and then, in the last two, we see where in complementarian marriages and church structures (so ‘authority’ in the church), men and women model a different way of relating that is not abusive, but nor does it allow women access to the ‘full picture’ of human flourishing (unless to flourish as a woman is somehow tied to helping the flourishing of a man, not to a shared task). For many it’s hard to see the difference between this last category of relating and the patriarchy/status quo. Some though read this model back into the garden of Eden, and it’s hard to unpick then how much sin and curse have changed the way we view and experience the default.

It’s fair to say that complementarianism grapples with the physical reality of our difference and acknowledges the way sin has made that difference worse. It is a realistic response to the broken world, but it does, in the hands of abusers, perpetuate abuse, and it’s hard to argue that overthrows systemic curse or injustice to replace it with something better. There are many ways that because it is realistic, not just idealistic, it’s actually better than option 2, it also seems to assume the Bible has good reasons to argue for/create different roles for men and women that aren’t simply cultural but are a response to sin and curse, but I don’t think it’s the ideal because it doesn’t appear to challenge or change the cursed and sinful status quo.

Subvert it (The cross)

Let’s return to that image from the start of the post…

It would be nice to simply remove the fence; but in this case the fence is ‘the patriarchy’ — it’s a human fence created by the status quo which involves men using their strength for our own benefit.

The world is geared towards the success of men. We’re bigger on average, stronger on average, faster on average, less vulnerable to sexual assault on average, get paid more on average, take less time off work for family on average. We’re more likely to be in positions of authority and influence because of many of these factors. This is what the patriarchy looks like; and sure, sometimes men get into these positions because of the voluntary sacrificial love of women in their lives who genuinely want to help them flourish, and for many Christians the flourishing life looks different to most of these criteria. It’s possible to theologise and suggest that this is what difference should look like, and that this difference creates, through the Gospel, a particular responsibility for the husband to love and serve his wife (this is the best version of option 3 looks like).

It would be nice to simply remove the barrier (ala the boxes and fence graphic above); or to get boxes for women to stand on so that we enjoy equity when it comes to our access to the flourishing life. But this does not factor in the real heart issue behind the barrier; the barrier is people, not just a ‘system’…

I want to suggest the Gospel actually provides us with a third way that is both like option 2 in its idealism and option 3 in its realism. Men following the example of Jesus and laying down our strength and even our natural-but-cursed claim to power and authority is a different way forward that produces qualitatively different outcomes as men and women operate as different and equal in our world. It needs a funky name; obviously; and some friends online call it being an imagodeian (imago dei is latin for ‘image of God’). When I was talking about this with my boss (credit where credit is due) he suggested ‘imaginarian’ which is nice, because we’ve been teasing out how important imagination is in responding to the cursed and sinfully twisted world as people shaped by the Gospel.

Do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit. Rather, in humility value others above yourselves, not looking to your own interests but each of you to the interests of the others.

In your relationships with one another, have the same mindset as Christ Jesus:

Who, being in very nature God,

did not consider equality with God something to be used to his own advantage;

rather, he made himself nothing

by taking the very nature of a servant,

being made in human likeness.

And being found in appearance as a man,

he humbled himself

by becoming obedient to death—

even death on a cross! — Philippians 2:3-8

Philippians 2 is the background for lots of what Paul says about gender relationships (eg Ephesians 5, and 1 Corinthians 11-14). Paul is a realist about both the difference between men and women, and the way the world makes this difference harmful to women, and he is giving us the good news that in the Gospel we have an answer to abuse and patriarchy; to sin and curse. We have the start of something new that will bring us towards a new reality, ultimately. Submission, then, which gets brought up in Ephesians 5 is both mutual (Ephesians 5:1), but also a preparedness to be served, to acknowledge that difference should play out in such a counter cultural way, and that this is the best and most counter-intuitive inversion of the patriarchy/curse and challenge to sin/abuse. Authority, then, is about casting one’s vote, or using one’s strength, for the sake of those you are serving. The cross utterly inverts human patterns of authority.

Now. Both egalitarians and complementarians will read this bit and say “he’s misunderstood us, this is what we’re already on about,” and to some extent this is true. There are good and true things in both systems… But this is how the Christian story gears us to think about gender relationships and flourishing in a fallen world, and it both realistically recognises that men and women are different, that the cursed world makes this difference particularly apparent for women, particularly when abuse is involved, so that it’s harder for all of us to flourish in this broken world.

The solution looks like this, because this is what it looks like for the stronger (on average, men) to use their strength by laying it down on behalf of those who sin and curse oppresses (on average, women). This is what it looks like to follow the example of Christ in all our relationships, or to love our wives as Christ loved the church and gave himself up for her. It doesn’t, and can’t, look like abuse and patriarchy; and equality on this side of the new creation doesn’t fight the systemic injustice (patriarchy) or sin (abuse). What this imaginarian approach looks like is perhaps more in the realm of ‘different and equal’; it acknowledges what is real, and what is ideal, and aims to recapture as much of the ideal and to live out as much of the new as possible, in marriage or church this looks like the powerful utterly renouncing the use of strength and power for personal gain or comfort, and instead using it to enable the flourishing of others as we raise them up, by lowering ourselves. This isn’t to say that women are exempt from sacrificial service (we’re all called to that in our relationships in Philippians 2), but this re-levels the playing field somewhat so that they’re in a stronger starting point in which to then give things up in their relationships too. Without us first addressing inequality by cancelling it out (giving up power that is not really ours to grasp) we actually double the ‘service burden’ on women. What this looks like concretely will be worth unpacking, but here, at least, is a visual (note, it’s a metaphor for overcoming the barrier as the strong give up strength to allow all of us to flourish, I’m not suggesting we join the circus).