As I dip my toes back into more regular blogging this year I’m hoping to be a little more proactive (and less reactive) with my writing. I’m planning to write a little less ‘deconstructive’ commentary on the church in the modern world, and a little more forward thinking ‘constructive’ material exploring the shifting landscape the church is operating in in Australia and possible implications for the shape of disciple making in our context.

I will, in the next little while, unpack some reflections on the last ten years — and my time in full time church ministry over this decade, and how that shapes where I think things maybe should go in the Aussie church, and some of that may feel less constructive, but I’m hoping to take that experience somewhere worthwhile (at least for me, and the community and denomination I find myself embedded in).

I’m particularly interested in exploring the role technology and technique play in how we adapt (and how the culture around us is adapting), and especially how these intersect with cultural changes around us. I’m not hoping to position myself as a ‘thought leader,’ I’m more thinking out loud from an evolving base of experience and research, hoping to participate in conversations that are happening both inside the church, and just in this cultural moment about the future shape of both church communities and society at large.

Basically, if you want to read someone who’s thinking about implications for churches, individual Christians, and society at large of machine learning or Artificial Intelligence, and its application in ChatGPT style content generation, or imagery and video using platforms like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, or Dall-E, that’s what I’m going to be playing around with (mostly) this year.

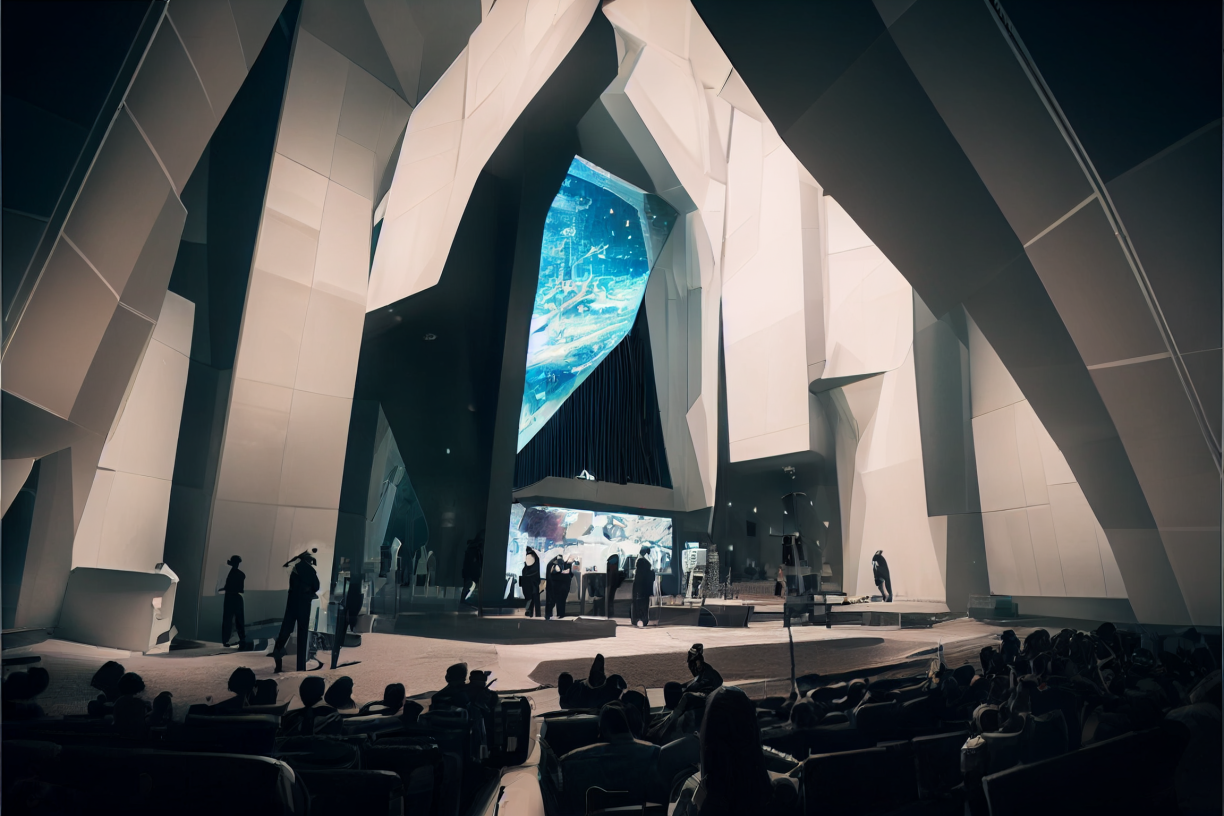

The image for this post was generated by Midjourney when I asked it for a picture of the church of the future.

As this new chapter starts out, here are 6 principles that’ll be driving some of my reflections. Long time readers will have seen me bang these drums before, and you could, of course, simply read Neil Postman’s essay 5 Things to know about Technology to find someone who says some’ve this stuff better and more predictively prophetically (both he and Marshall McLuhan were way ahead of the curve).

Technology is not neutral (it’s ecological).

Marshall McLuhan once said “our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot.” I think he was right. Not just about this. One of his students, Father John Culkin said “we shape our tools and thereafter they shape us” — when we introduce a bunch of new tools into our lives the impact on our lives as we use these tools reshapes us in ways we don’t always see. This’s true in our individual lives, in our homes and families, and in our churches. I wrote a little about this at the start of the pandemic as churches rushed towards technological solutions to the challenges restrictions presented to the shape and rhythms of our communities.

Technology is mythic (tending towards idolatry).

Another way that technology isn’t neutral is that it’s always created for a reason, by people operating with a vision of the good life (and problems to be solved or capacities to be extended). We might think we can simply pick up a tool and use it separate from this purpose, but that’s particularly difficult the more a technology is connected to a ‘mythology’ — an organising story about the world and life in it (and the more that mythology is embedded in the technology in the form of ‘operating systems’/software/algorithms to carry the values and vision of the maker). Technology often comes with an anthropology (an understanding of what it means to be human) and an eschatology (an understanding of the future horizon it pushes us towards), these anthropologies and eschatologies are often quasi-religious (or explicitly religious) in nature.

In his essay (linked above), Postman says: “every technology has a philosophy which is given expression in how the technology makes people use their minds, in what it makes us do with our bodies, in how it codifies the world, in which of our senses it amplifies, in which of our emotional and intellectual tendencies it disregards,” and “our enthusiasm for technology can turn into a form of idolatry and our belief in its beneficence can be a false absolute.”

Technology-making is human, and can be oriented towards right uses of creation.

The command to ‘be fruitful and multiply’ and to ‘fill the earth and subdue it,’ followed by the story where the archetypal humans in the heaven-on-earth space are placed in a garden to ‘cultivate and keep it,’ where we’re told about all the goodness and beauty in the surrounding earth, lends itself to the idea that humans aren’t meant to just work with their bare hands, but we’re to make tools. Tools that would shape the world, and re-shape us. The first genealogy after the garden tells us about people making tools, instruments, and cultivating the land. Throughout the Old Testament artisans and makers are said to have God’s Spirit of wisdom, these’re the folks who make the furnishings for the Tabernacle and Temple, and build those heaven on earth spaces (that look like Eden). No all technology is evil; imagining and making technology to reshape ourselves, and the world, towards a true human telos (our created function/purpose) is a profoundly good thing to do and is part of being made in the image of a maker. The catch is we’re people who live with hearts turned in on ourselves, and away from God, and so our technology tends to amplify that nature as it takes on mythic (and idolatrous) qualities. The Babylonians get pretty good at making technology (and cities and towers and stuff). For more on this idea check out my piece on the brilliant Bluey episode, Flatpack.

Image-making particularly amplifies these dynamics, in part by shaping our imaginations as we produce artefacts and art.

We are images who make images — just as God was able to conceive of a world and fashion it into being — via his word, and with humans in the garden, by breathing his life into a human he crafted from the ground, we are able to imagine worlds and bring them into being (in our stories) and to craft things with our hands. Images are particularly powerful ‘imagination-primers’ which is, in part, why God commanded Israel not to make images of himself, or other gods, who would corrupt their imaginations and so their actions in the world with false imaginings of God and of the sort of lives we should go making with our hands. Our ability to now generate and manipulate digital imagery has extended this capacity to new, and sometimes terrifying, levels.

Cultural change doesn’t simply happen ‘top down’ via ideas and images, but bottom up through ‘things’ that shape our lives (like cameras)

Lots of our theories and fears around cultural change — and the stories we tell about how we got to where we are — focus on the ideas (often the ideas of “great men” in history, or on the ideological takeover of institutions that educate and form people). This is partly because we’re conditioned to imagine ourselves as brains on a stick (or our brains as computers) who operate in response to data/information.

History is full of big ideas — it’s quite possible that the ones that stick are the ones that are coupled best with technologies and artefacts that embed the ideas in the actual lives of people (this isn’t to say that these ideas can’t also be true). So, for example, the Protestant Reformation took hold in part not just because the printing press emerged as a technology, but because it supported the ideas of the Reformation (that information shouldn’t be restricted to a priesthood), and got books written in the vernacular (a new technology) into the hands of the masses. This sort of change via technology (and the ecological change it brings, and mythology it creates) is observable throughout history and so when we think about social and cultural changes it’s insufficient just to think about ideas, we have to think about tools and techniques and the practices they embed in our lives as they re-shape us (individually and collectively) as well (and we need to think about who supplies the tools, to what end, and how they benefit as well). And when it comes to digital/electronic technology we need to examine the practices created as we interact with both hardware (like a mobile phone) and software (like an algorithm deciding what content we see).

Technology causes secularisation.

I’ve put this one last, because it’s the biggest — and it’s probably the most cautionary point of all the above; it’s also an outworking of the previous points. There are lots of theories about what enables secularisation — what it is that disenchants our vision of reality, or kills G0d (or gods) in our imaginations, our image making, and the lives we live in the world with any sense of plausibility — these often focus heavily on shifts in thinking, or in practices (around things like sex). My friend Stephen McAlpine writes a lot about the sexular age; linking our modern western approach to sexuality, identity and transcendence to how we approach sex.

Here’s me coining the Techular Age.

Technology causes secularisation — new technologies like clocks and computers changed the way we conceived of God, and the world, and our life in it — and when we’re faced with problems that once seemed insurmountable, or with suffering and death, it’s technology we often turn to for hope and that gives us a vision of the future. Technology even enabled the sexual revolution through things like the pill, and continues to shape the way we approach sexuality as ‘expressive individuals’ as we engage in relationships (or just sex) facilitated by apps (with algorithms) on our phones (that serve up imagery), or through imagination-shaping digital images (like pornography) that teach humans how to interact with one another (with not great consequences). I’ll unpack this more in future posts, but it’s this last point that makes me want to tread more carefully than all the others when it comes to imagining the future shape of church communities and the role technology plays in our life together.

Even if ChatGPT thinks the church of 2050 will need to incorporate emerging technologies. Here’s what it suggested when I asked how churches might incorporate emerging technologies in the next thirty years.

“There are many possibilities for how emerging technologies could be used in a church setting, depending on the specific technologies and social trends that are present at the time. Some examples of emerging technologies that could potentially be used in a church setting in the future include:

- Artificial intelligence: This could be used to create personalized recommendations for biblical studies or spiritual growth, or to provide answers to frequently asked questions.

- Virtual and augmented reality: These technologies could be used to create immersive experiences for worship, Bible study, or other events. For example, a church could use virtual reality to take members on a virtual tour of biblical sites, or to create a simulated gathering space for virtual services.

- Blockchain: This technology could be used to securely track donations, manage membership records, or facilitate online transactions.

- 3D printing: This could be used to create physical copies of biblical artifacts or other objects for use in worship or educational settings.

In terms of social trends, it is likely that churches will continue to embrace the use of technology to reach and connect with members, particularly as more people become comfortable with using technology in their daily lives. Some churches may also focus on creating more inclusive and diverse communities, and may use technology to facilitate this by providing translation services or creating virtual gathering spaces for underrepresented groups.”