This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2021. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 38 minutes.

Last time round we set the scene for Revelation by looking back through the Bible at the way some of its key language ties up a big storyline thread. The idea is that we humans are either destined to become beastly, like the serpent, Satan, or beautiful, reflecting the glory of God. We saw that this choice boils down to who, or what, we worship — Jesus, and through Him, the God who created the heavens and the earth, or beastly rulers of the earth, and through them, Satan.

And we saw that this was a real and present challenge facing John’s first readers — those he wrote this strange book to. The challenge for us now is not seeing the big story this book fits into, but figuring out how to read it in our circumstances here in Brisbane, two thousand years later.

Just what sort of book is Revelation? What place does it have in our lives as followers of Jesus? What is its message for us?

The book gets its name from the first line — this opening — the ‘revelation from Jesus Christ’ (Revelation 1:1). There is a lot to unpack here as we figure out how to read it, and the first thing to note is that this word is literally ‘apocalypse.’ It is ‘the apocalypse from Jesus Christ.’

Now, we think we know what an apocalypse is, right? You have probably got an escape plan you have figured out for the Zombie apocalypse — especially after Covid — right? Or maybe that is just me.

We know an apocalypse is about the end of the world. Don’t we?

Only, that is just what we have made this word mean because of one way this book has been read, and I’m pretty convinced that is not the right way.

An apocalypse is not about the end of the world like ‘how it all falls apart,’ It might be more connected to the ‘ends of the world;’ the way philosophers talk about purpose, or like some of you might have learned, ‘the chief end of man is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.’ But the thing is, this word more literally means something like revelation; an unveiling. It is about truth being revealed that helps us see events around us — to see the world — the right way — and in the sense it is used in the Bible, it is like a veil pulled back moment where we see earth and its purpose — and our purpose — from the perspective of heaven.

Now, it is possible this apocalypse is all about the fire and brimstone end of the line for the earth — that it is an ancient document predicting events in the far-off future. That is one possible reading of the book. The locusts could be Apache helicopters, and the mark of the beast could be bank cards — but these are readings of the book that always put present or future generations in the audience seat, at the expense of the past.

And that can be tempting.

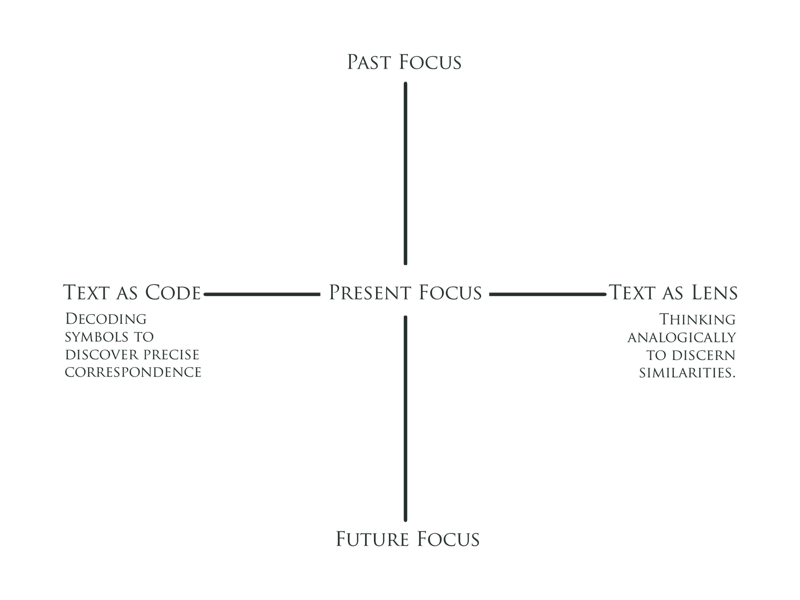

The Biblical scholar Michael Gorman has a book called ‘Reading Revelation Responsibly,’ which has this great graph to explain how people read the book. He reckons all of us naturally fit somewhere on this graph.

We can treat — from top to bottom — the book as though it only describes events in the past, or as though it is about the present or the future, or a thing that encompasses all points in time. On the left right axis, we can treat the vivid apocalyptic symbols as codes that describe particular phenomenon located at a certain time (the up-down axis), or we can use these symbols like a lens; a way of seeing the world, and events either everywhere on the up/down axis or in a particular spot. So we either approach the book decoding symbols to discover precise moments they correspond to in history, or see the symbols as analogies that will explain various things that might happen at any moment — giving us a language to understand reality.

You might remember how I’ve got these colour-blind lenses that allow me to see colours I did not know existed; reds and greens like never before. These lenses change the way I understand the world by revealing things I could not see without them.

I am going to suggest — like Gorman — and like a couple of other people I will reference along the way — that we should be thinking of Revelation as supplying us with a set of lenses to see the empires of the world with God’s eyes — and that this had a particular and urgent meaning in first-century Rome (where the symbols do have a coded meaning), but we can use these lenses today too.

Part of what this book does, as a lens, is it sits us in the heavenly courts — in the heavenly realm — away from the day-to-day trenches of normal life and it invites us to see that not only is that realm real, it is the one that matters — because what goes on in the heavens, in the Bible, shapes what happens on earth.

And this means we get a bunch of vivid language, and out-there pictures, to try to disconnect us — dislocate us — from earth.

But we also get earthly things described in caricatures that expose or unveil them as what they are.

There is a good analogy for this in a piece by Aussie theologian George Athas, where he talks about how Revelation and other literature like it functions like political cartoons that exaggerate certain features to expose them.

For now, let’s imagine that when John writes his revelation, his goal is to give us a lens that unveils the world for us and invites us to see it as God does. Also, it can be so easy for modern readers to think Revelation is a coded message book about evil beings and spiritual opposition and all the bad stuff that applies — that these are the focus; but Revelation points the lens somewhere else. First and foremost, and from start to finish (like the rest of the Bible), Revelation is about Jesus.

It is not just from Jesus (Revelation 1:1). The way Greek works mean this could either be a ‘from’ or an ‘of.’ You will find English translations that do this — it is an unveiling that does not just come from Jesus, but it is a book that unveils Jesus for us and invites us to see the world anew, having seen Jesus as he is.

Revelation zooms in to the throne room of God where Jesus now rules from the throne as King of Kings and the Lord of All Nations.

But that is not all John tells us, and here is one of the first reasons I think the book sits where it does on that graph. John tells us that this vision of Jesus, from Jesus, was given to him, by God, to show his servants — his people — what must soon take place (Revelation 1:1). Now, we might think that ‘soon’ applies to us; that we are the generation these words have been waiting for. But, it is much more likely that this is a letter that first applied to the present and very near future of its first readers — and that it drew on analogies and imagery from the whole Old Testament to reframe their understanding of life in Rome.

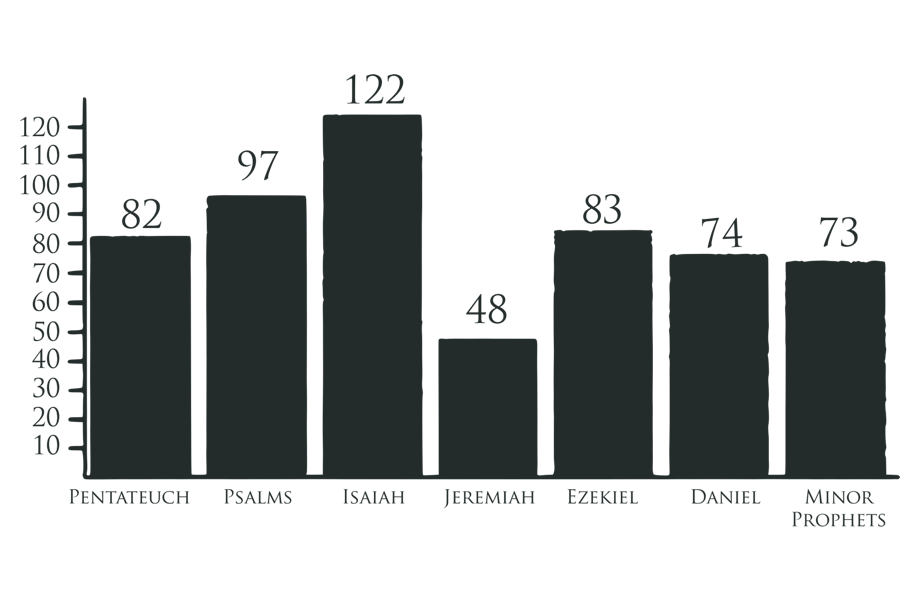

Revelation is absolutely soaked in Old Testament references or allusions — one scholar who tabled them all up — Stephen Moyise – did up this graph of the books John draws from. He found Revelation draws extensively on the whole Old Testament as it paints a vivid picture using big cosmic language.

One scholar says there are more allusions to the Old Testament in Revelation than the rest of the New Testament put together. This depends a bit on how you define an allusion, but what cannot be denied is how richly Revelation sits in that tradition and applies symbols and language from the Old Testament to a particular moment in time.

Or that the central message is the idea that Jesus is the fulfillment of the Old Testament expectation that God would reign as king.

And that is what John has come to testify — to the things he saw — and John can sum up his vision by saying that what he is testifying to — is the Word of God and the Testimony about Jesus (Revelation 1:2).

And it is this same testimony that Jesus is King, not Caesar that has John in a prison island — on Patmos. He is there because of ‘the Word of God and the Testimony about Jesus’; the same thing verse 4 says is the heart of this message he has passed on in this book (Revelation 1:4, 9).

And this book — it is not just an apocalypse — an old bloke yelling at clouds about a broken world — to nobody; it is a mix of genres. John is like an Old Testament prophet. There is a prophetic dimension to the book.

John describes himself being in the Spirit; of being taken up to see things from heaven and being told to write down what you see. This is the classic way that an Old Testament prophet, like Ezekiel, or Daniel, would introduce an apocalyptic vision or prophecy like this. John is plonking himself down in that role (Revelation 1:10).

But it is also a letter sent to particular churches at a particular time (Revelation 1:4). It is like any other New Testament letter. We have to figure out what it says to a church in its immediate context before we apply it to our moment in the sun.

And while the number 7 gets a fair bit of air time in Revelation as a symbol of completion or perfection — even in our passage today — these seven churches were real churches, and John names them: Ephesus, Smyrna, Pergameum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea. John’s vision is for them (Revelation 1:10-11).

So this apocalyptic prophecy is, first of all, a letter to real churches, in real cities living under Roman rule. It’s a mix of genres, but it’s written by a person, to other people, at a particular point in history.

Whatever we want to make of it — wherever we want to see Revelation speaking, it feels odd if we say it has nothing immediate to say to these seven churches.

I reckon this means we can’t think so much of the text as a code that speaks to the present or our future, as though what John saw corresponds directly with events still to come that had nothing to say to these churches. And yet, at the same time, John uses the number seven over and over again in the book as a number of completeness. There would’ve been stacks more churches just in the towns and cities of the provinces he mentions, but he picks seven because seven is a way to say “this is for the full church.”

It has a particular and immediate audience who received the written work, who it must be meaningful to — just like Daniel and Ezekiel were to their first readers — but also a sort of ‘universal’ audience as well.

These churches are soaked in the religious and political messaging of Rome — churches called by the bright lights of the big cities, and by the bread and circuses of Rome to worship the emperor.

Which, if you remember last post — was an empire whose “proper procedure” was, at certain points, to execute those who would not worship Caesar.

So John dips back into Old Testament imagery that is used as a lens to look at Old Testament empires and says “hey, have a look at this Roman power from God’s perspective,” but more than that, it says “have a look at Jesus from God’s perspective and choose who you’ll worship.”

And the last thing to notice from the intro is that it’s not a book that is meant to be read and atomized — primarily — into verse by verse ‘pull apart the grammar’ stuff like we modern people like to do — and one of the reasons we do this — that we have to — is that the symbols in this book all mean something to the first hearers based on how familiar they are with their own context, and with the Old Testament. We don’t have that familiarity, or that context.

But it’s a book to be experienced — to be read aloud and heard (Revelation 1:3). The symbols are meant to come thick and fast, like a good audio-visual experience; leaving us a bit breathless and overawed by what we hear.

But also hearing the message and taking it to heart, and as one more hint that John has immediate concerns, he says the time for applying this is near (Revelation 1:3).

This decision to take this unveiling to heart, to re-see the world through the lens it supplies is what leads to blessing, that’s going to be a big theme the book picks up right at the end as it returns us to a picture of a world not marked by the curse of sin and death.

Revelation — this apocalypse — is meant to do a work on its hearers reframing the way they see the world, and its rulers.

And if, as we saw last week, the presenting challenge for these first-century churches is choosing who to worship and what kingdom to serve, the apocalyptic letter opens by framing our vision by pointing the lens firmly not at Rome, but at the heavenly courts.

John is writing on behalf of the Ancient of Days — the one who was and is and is to come (Revelation 1:4-5). John uses a whole lot of different titles for God in this book, and he uses them really deliberately in patterns that help structure the book, but this is such a big way to describe God.

God isn’t just a being in creation, he is the I Am — that ancient name for God, and he always has and always will be. John plays with the I Am name in his language here to say God always is, and God the father is giving grace and peace to his church.

And so is the Holy Spirit — and here’s another time the number seven pops up in this book and most scholars see this “Seven Spirits” reference as a reference to the completeness of the Holy Spirit (Revelation 1:4), but also as a way of saying this is the Spirit at work in the seven churches, because it’s the Spirit at work in all the churches.

And John is also writing from Jesus Christ, the faithful witness and ruler of the kings of the earth (Revelation 1:5), these are hints that for John, Daniel’s vision that we saw last week has been fulfilled already.

And then John, overwhelmed by this sense of God speaking to his church, breaks out in a moment of spontaneous worship (Revelation 1:5-6). This is what some of you might know as a doxology — which is a word that means words giving glory to God.

John is giving glory to Jesus, and to the Father, because Jesus has created a kingdom; not a beastly kingdom but a priestly kingdom; a reference to what God made Israel to be in Exodus (Exodus 19) but applied to the church.

Not a kingdom of violent dominion but a kingdom of servants of God, for his glory, secured by his blood.

John grounds his vision — his unveiling of reality — in the victory of Jesus that has already happened; the victory of God over sin, and death, and Satan and all the beastly kingdoms and humans who follow the way of the serpent into beastliness.

And here’s one of those points where John just combines Old Testament references. You’ve got Daniel 7, which we looked at last week, and Zechariah chapter 12. But here is also where John starts giving us the perspective of the heavenly courtroom where the Son of Man is coming with the clouds — the ascended Jesus is taking his seat, fulfilling Daniel’s vision (Revelation 1:7).

Where God the father, the Almighty — the one who was and is and is to come — now calls himself what John called him in verse 4 and adds that he’s the Alpha and the Omega — the first and the last (Revelation 1:8). This is a big picture of the God who sits on the throne of heaven and rules all nations; the one in whom we live and breathe and have our being, who has the past, present, and future in his hands.

And so the message for God’s people is that they have to pick their king.

They have to choose a kingdom.

They have to choose between this God’s beautiful forever kingdom and the violent and beastly kingdoms of the world.

And John, as he looks into this heavenly court, doesn’t just hear God’s voice — he sees the voice coming from someone, and when he turns he sees this figure like a “son of man” among these seven lampstands (Revelation 1:12-13).

We’re told later are churches (Revelation 1:20), but this lamp imagery also comes from the temple, and a heavenly vision of the temple in Zechariah; and this speaking figure is in this cosmic temple present with the churches, and he’s dressed like a royal priest and looks like the Son of Man from Daniel’s vision.

When John describes him he says:

“The hair on his head was white like wool, as white as snow, and his eyes were like blazing fire. His feet were like bronze glowing in a furnace, and his voice was like the sound of rushing waters.”

This pulls all sorts of Old Testament imagery about God together — the ‘voice like the waters’ bit comes from Ezekiel, and there’s a throwback to Daniel here too (Daniel 7:9).

John brings Daniel’s vision of the Ancient of Days, God, together with Daniel’s vision of the Son of Man arriving, so that God and the Son of Man are brought together in this rich new way where the Son of Man is speaking as the voice or word of God.

He sees Jesus as this glorious bright glowing light. White and bright.

Just like animal skins were a code for beastliness in Genesis 3, this sort of imagery is a code for glory; for a heavenly being; we see it at a few points in the story of the Bible.

Like at the transfiguration — another unveiling — where the disciples see Jesus as he really is — one shining like the sun, and dressed in white (Matthew 17:2).

And it’s the same imagery at the resurrection, this time with an angel of the Lord whose appearance is “like lightning” and his clothes as white as snow (Matthew 28:2-3).

Hebrews talks about the son, Jesus, as the “radiance of God’s glory;” another shining word (Hebrews 1:3). John’s point with all this language is that he is the glorious ruler of the heavens and the earth — the heavenly bodies that were viewed as being divine beings in the ancient world reflect him, rather than the other way around.

John is picturing the Son of Man as this triumphant and victorious heavenly king who is glorious — shining with the light and life of God himself and who rules the heavens and the earth — the seven stars — if seven is about completeness are a picture of Jesus’ authority over the heavenly bodies as well as the earthly ones (Revelation 1:16). John tells us at the end of the chapter that they are a picture of the angels, or heavenly beings, being in Jesus’ authority.

Whatever all this means, whether we understand the imagery or not, it is intended to be beautiful, glorious, and terrifying in its over-the-top glory. It pulls together threads of similar unveilings in the Old Testament to emphasize that Jesus, whom Christians might follow as king, is divine.

John concludes this by describing Jesus as the first and the last (Revelation 1:17-18), in the same manner he has been describing God. He connects Jesus’ victory over death, Hades, the dragon, and his curse to Jesus’ own death and resurrection. Jesus is the living one.

John’s testimony about Jesus is that the crucifixion and resurrection reveal God to us, for in them the God-man, the son of God and Son of Man, is unveiled and victorious.

When we see Jesus this way, John’s response is to fall down in awe, worship, and submission (Revelation 1:17). No other king or god commands John’s devotion through their presentation of their glory.

Remember Trajan, the emperor whom Pliny wrote to. He agreed with the notion that citizens must worship Roman gods, including the emperor, or face death. However, he offered salvation from death, a pardon, through repentance and worship.

The choice facing first-century citizens was to repent and worship Caesar and his empire to receive his pardon and life in his kingdom, or repent and worship Jesus and receive life in His kingdom.

John’s vision is the lens he wants the church, the seven churches he is writing to, and all the churches they represent, to see the world through. This lens challenges us to look beyond any other pretenders to the throne, anyone or anything else that might command our worship.

How can other empires compete with the glorious one? How can we worship anything else?

This lens is something we might want to use in our own times too, as we look at empires, agendas, and objects of worship that offer us life and call us to give ourselves up, pulling us away from God and His kingdom.

Choosing between God-kings should be easy if this is what the throne room of heaven looks like, and who the one on the throne appears to be. Jesus isn’t a distant king; He is Lord of His church.

The Jesus John sees is not just in heaven, absent from the concerns of His people. He is present with His church, operating as a priest for the church in the heavens. This is a theme we see elsewhere in the New Testament. He brings us into God’s presence, which is where the book will lead.

He is the faithful witness who shows us what God is like and what faithfulness to God in the face of beastly empires looks like, trusting God to win and bring blessing. This is where the book will go.

Jesus, the living one, was dead and is now alive, offering hope of new life and resurrection to His people. This is where the book will go. As the first and the last, he will return to make God’s victory and his kingdom absolute, bringing all other kings to their knees because God is the Most High, and Jesus is his voice and chosen ruler (Revelation 1:17-18).

He has freed us from our sins, from the curse, death, and the claws of Satan by His blood, through His death and resurrection. Like in the Exodus with Israel on the mountain, He has made us a kingdom of priests, acting as our priest before His Father (Revelation 1:5-6), even as he, himself, is God. He is the one to be worshipped and glorified, with His Father.

In doing so, we too will be clothed in glory; we too will be swept up in the beauty of God’s vision for His people (Revelation 7:9).

This vision will drive what John has to say about politics and economics — about how we live as people, as the church.

Is it your vision, your lens for looking at reality?

Does it shape your worship?

Your life?