This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2021. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 42 minutes.

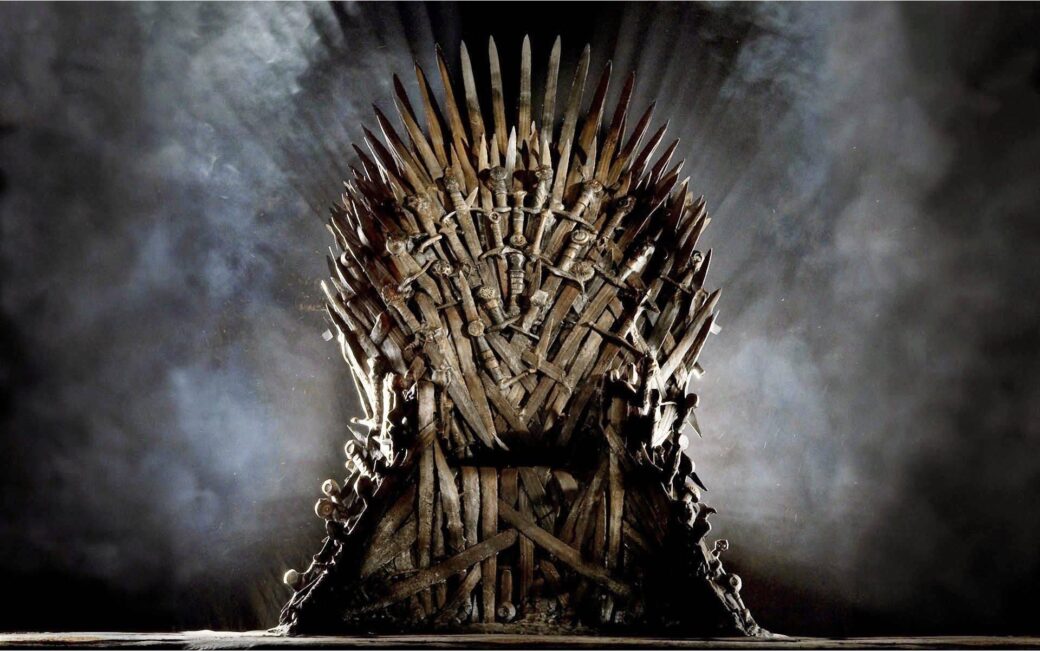

You can tell a lot about a king — or a kingdom — by the throne and the throne room, and who is in it.

Like the throne in “Game of Thrones” — a throne made of swords — to remind anyone who sits on it their rule is secured by the sword, and will be ended by one.

“Game of Thrones” is a hyper-violent show based on a series of books that are a deep dive into the violence at the heart of modern empires.

It is a bit like the Netflix sensation [current at the time of preaching] — “Squid Game” — the hyper-violent series aiming to expose and critique the violence at the heart of capitalism, where the haves capitalise on the have nots, in the show the super-wealthy sit on thrones watching people indebted by the system give their lives in violent games, hoping to win financial freedom.

The catch is we are so enmeshed in the system these shows critique that instead of being shocked, and exposed, we find ourselves sitting in this same chair, embracing the fruits of the system and the entertainment it uses to keep us from revolution.

Empires built on immersive violence as entertainment are not all that new. In fact, this was part and parcel of the Roman empire around the time Revelation was written.

The person occupying the throne in Rome embodied the worst of the political and economic realities “Game of Thrones” and “Squid Game” unpacked, but when you were enjoying the show it was hard to escape… The throne needs to be seen from a different angle.

And that is what this Revelation does.

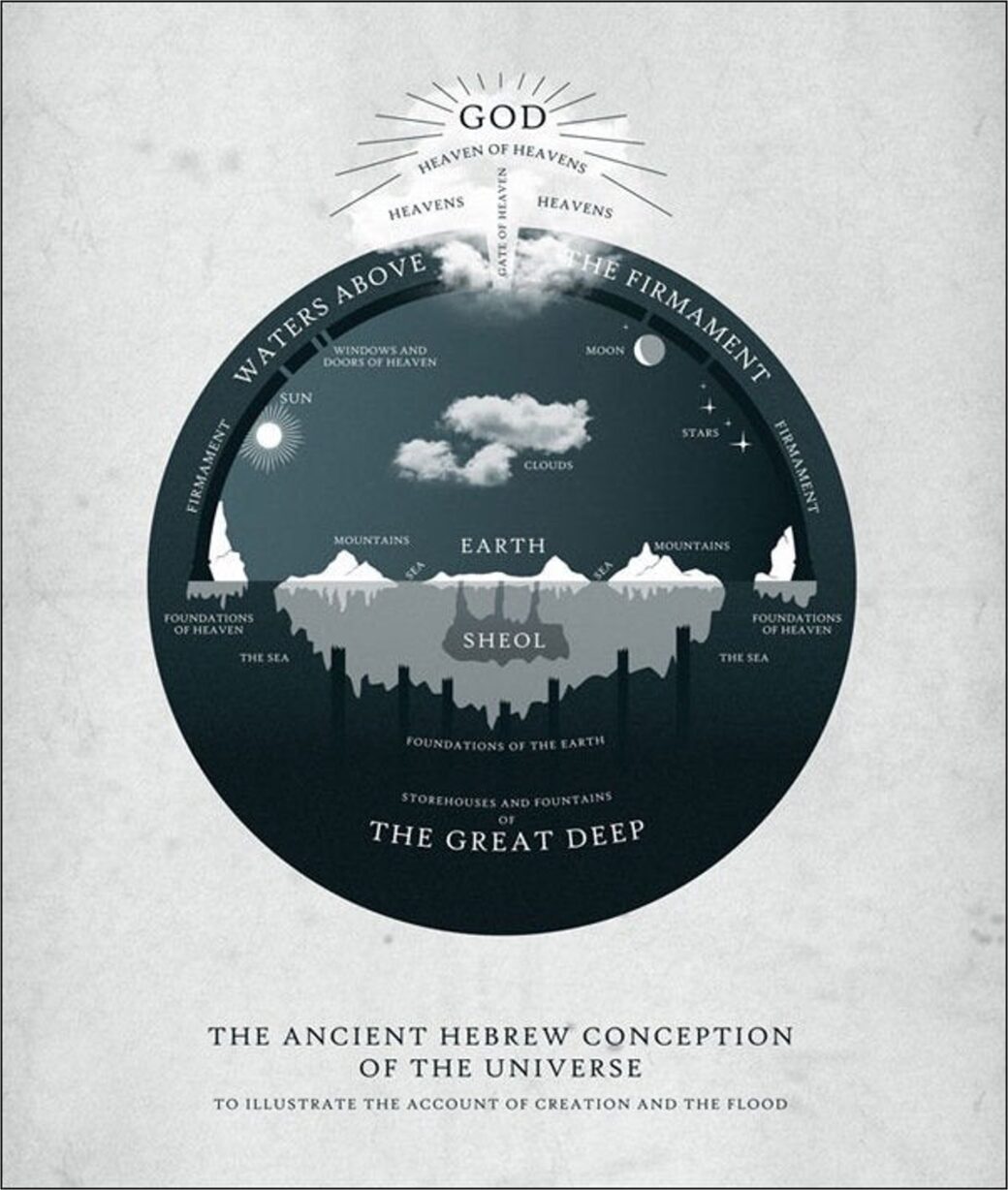

John’s vision now zooms in on the throne in heaven (Revelation 4:2). There is some imagery that carries over — seven lamps are blazing — seven lamps perhaps sitting on the seven lampstands —these lamps are the spirit of God blazing; shining light on the throne. Thunder and lightning are rolling out (Revelation 4:5).

There are twenty-four elders around the throne, or, literally, twenty-four Presbyterians (Revelation 4:4), and we will see more of them later. Then we zoom out on these four living creatures who are “covered with eyes, in front and in back…” one is “like a lion”, the next “an ox,” the third has “a face like a man,” and the last “was like a flying eagle” (Revelation 4:6-8). They sound weird, but we have met them before.

They were in the heavenly throne room in Ezekiel (Ezekiel 1:5). There are some little differences, but in both scenes they are these critters that are this mix of the human and beast; the same animals (Revelation 4:6-8, Ezekiel 1:10). In Revelation these critters have six wings, but in Ezekiel, they had four. We are told the identity of these heavenly creatures in Ezekiel.

These weird lion-man-cow-eagles are cherubs. Cherubim is the Hebrew plural for cherubs.

You might picture a cherub like this.

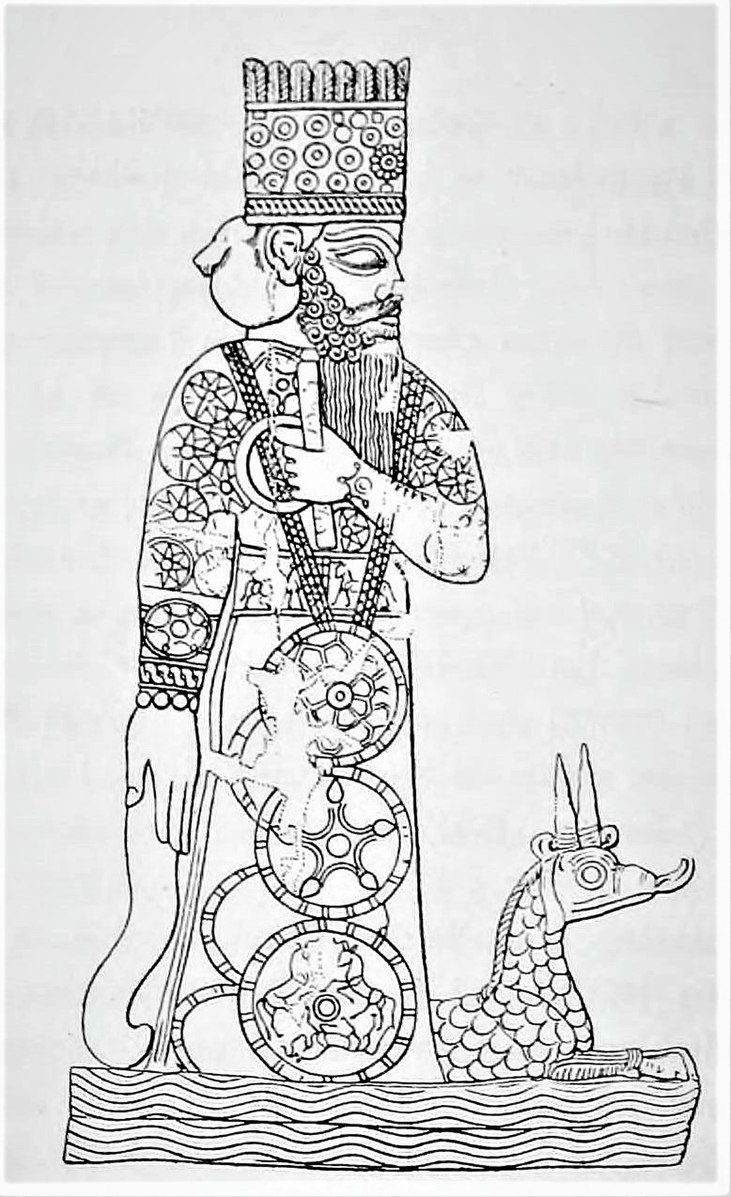

But according to the Bible, they are beastly creatures who look more like this:

And the thing is — this picture of these heavenly beings that serve and worship Israel’s God — these did not come from a vacuum. The prophets in the Bible are making a point here.

It is not that cherubim actually look like this; they are a visual commentary, drawing on the thought world and gods of the nations to make the point that worshipping lesser spiritual beings from God’s divine court makes no sense when it is actually God who is on the throne.

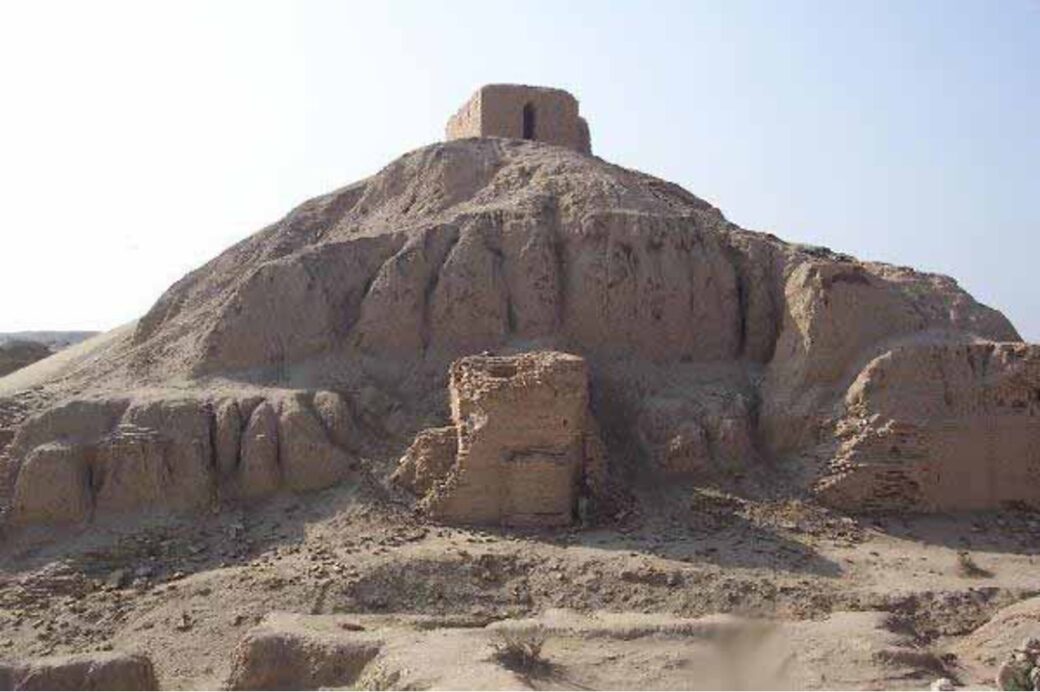

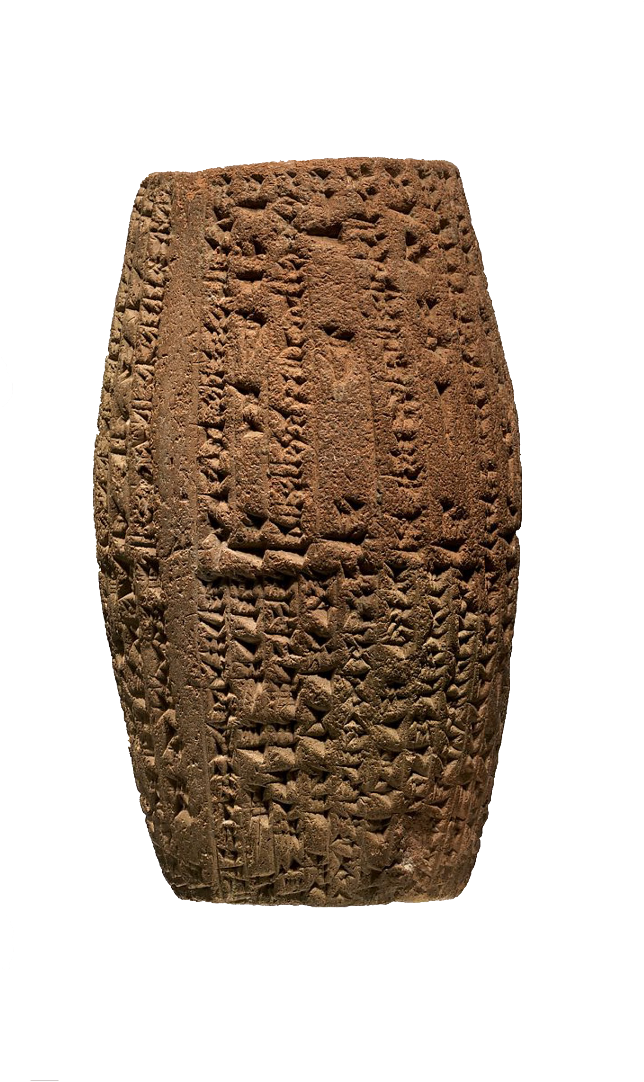

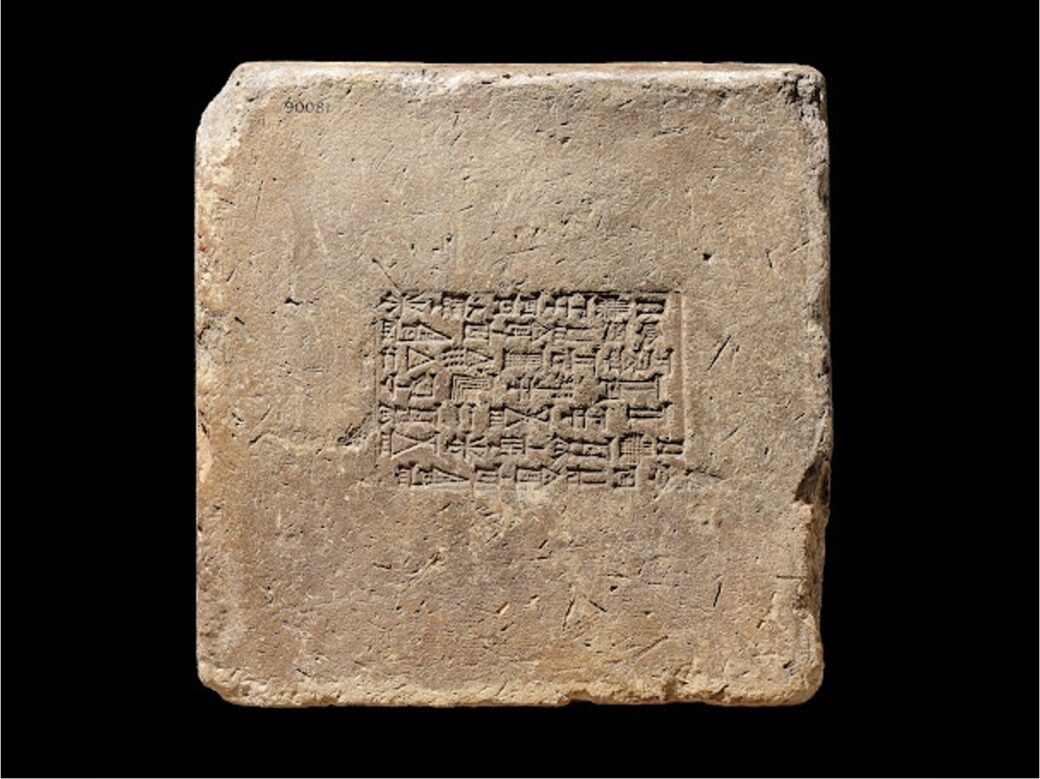

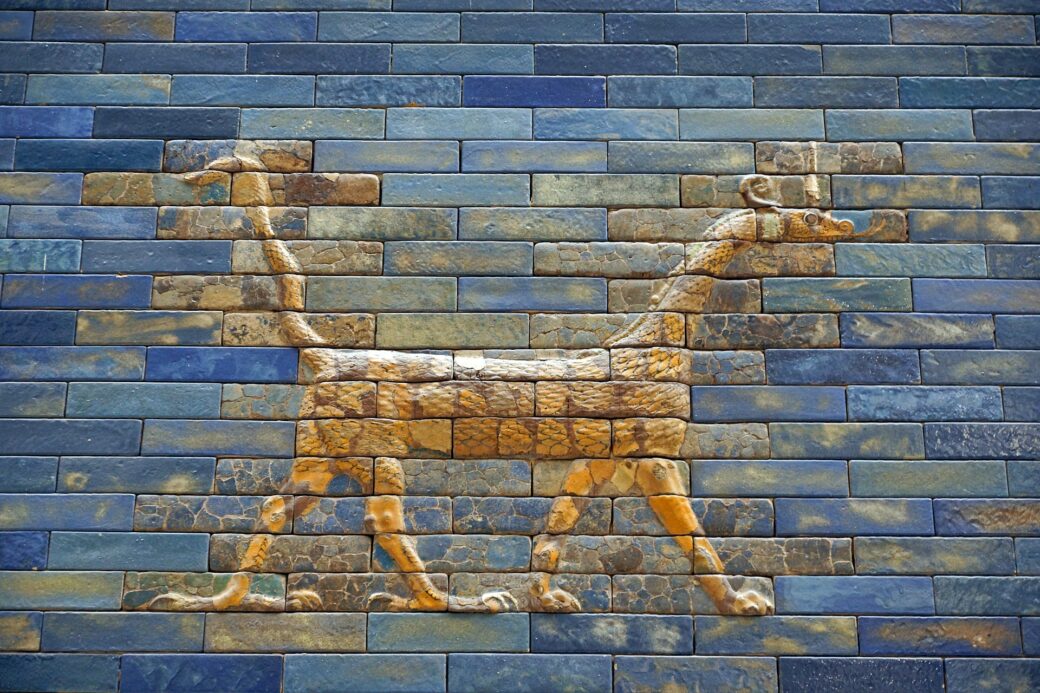

Remember, these empires around Israel worshipped images of beastly gods — serpents, dragons, weird hybrid animals like this Babylonian picture.

Their stories were violent and bloody and their kings were supported by beastly supernatural beings — gods — who triumphed, tooth and claw, over other beastly gods.

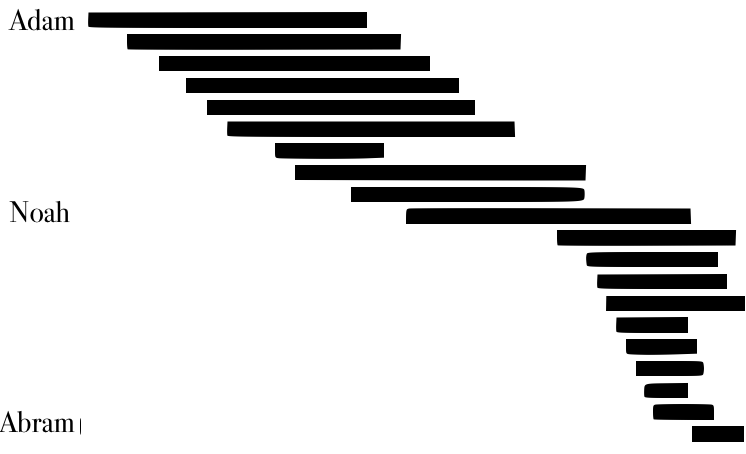

And we saw how Daniel makes the connection clear, even with Nebuchadnezzar running off to the wilderness looking like the beast gods (like the cherubim) Babylon was tempted to worship in the place of the Almighty (Revelation 4:7-8, Daniel 4:33).

These cherubim are an amalgam of these beast gods, only, they are not superior beings, but servants of Israel’s God; worshippers of Israel’s God. To worship them would be a big mistake. Isaiah does the same thing with some six-winged critters; the seraphim (Isaiah 6:2).

John’s vision brings the cherubim and seraphim together.

We might picture cherubs as little angels with wings, but seraphim — the word means both burning as a verb, and snake, as a noun, and there is a good case to think that seraphim are actually flying fire serpents. The word might have its origin in cobras who spit venom. These winged snakes were a popular religious image in Egypt — where they were a cosmic symbol of divine authority.

Pharaohs even had them on their crowns. But Ezekiel and Isaiah – then Revelation – picture these beastly heavenly creatures not as objects of worship, but as worshippers of the Almighty who sing praise to him (Revelation 4:8, Isaiah 6:2).

Why would you worship other spiritual creatures who sing “holy holy holy is the Lord God Almighty”?

John’s vision pulls together these threads to show the position God occupies in the heavens; as absolute ruler over the so-called gods of the nations.

But there is more, because the cherubim had a job. They were divine gatekeepers, keeping sinful people out of God’s presence.

When humanity gets exiled from God’s presence — in Eden — cherubim guard the way (Genesis 3:24). When Israel operates as God’s priestly kingdom, carrying God’s presence with them in the tabernacle, cherubim symbolically separate people from God’s presence in the holy of holies (Exodus 26:30-31). The curtain in the tabernacle, and then the temple — the one that tore when Jesus died — was a cherubim guarded barrier between God’s holiness and the people — part of it tearing at the death of Jesus was because that barrier is now broken, but part of it was also a picture of God declaring he will not live in that temple. Statues of cherubim framed the Ark of the covenant in the Holy of Holies (1 Kings 6:27). The Ark was a physical picture of the throne of God, and the cherubim were keeping the people from God’s presence, except a priest, once a year, keeping humans away from the presence of the holy, holy, holy, God.

Here in Revelation these cherubim are not excluding people from God’s presence. They are these powerful awe-inspiring cosmic beings who draw the eye — but we are not meant to gaze at these crazy critters. Because their gaze is fixed on someone else.

We might be tempted, by all this descriptive language, to keep our eyes on the weird heavenly beings.

Especially if they represent some sort of powers or rulers of the kingdoms of the world who might impact us. Where Ezekiel’s vision ends with the camera pointed at this glorious figure “like that of a man” on the throne (Ezekiel 1:26), John opens with our gaze firmly on the throne; on this figure (Revelation 4:2), who like in Ezekiel, is surrounded by rainbows and light and glory (Ezekiel 1:27, Revelation 4:2-3).

The lens zooms out on another miracle — Presbyterians moving their bodies in worship (Revelation 4:9-10). When the cherubim and seraphim worship the one on the throne, these twenty-four elders join in. Now there is a lot of debate about who these elders represent, whether they are spiritual beings who are part of the divine council that gets mentioned in the Old Testament a bit — or glorified humans — ruling with God — but these creatures have crowns, and they lay them down in recognition of God’s rule… and say:

“You are worthy, our Lord and God, to receive glory and honor and power, for you created all things, and by your will they were created and have their being.” (Revelation 4:11).

I think these are probably also meant to be spiritual beings; the powers and principalities the Old Testament pictures ruling over the nations, and those who Jesus now rules over as the king of kings and Lord of Lords.

I recognise how weird and otherworldly this all is, but remember this is a letter written to real churches in the first century and this sort of vision of the cosmos was bread and butter. Especially with an emperor claiming his ancestors had ascended to the heavens to rule as gods within a council of gods.

But there is an Old Testament background here too. Isaiah the prophet anticipated a day of the Lord, when judgment would be dished out on the earth; not just on people, but any powers and principalities — those beastly nations — who had stolen Israel’s hearts through false worship. Isaiah anticipates this day when God will come in judgment, laying waste on the earth (Isaiah 24:1), and punishing the cooperating rebels on earth and in heaven – the powers in the heavens, and the kings of the earth (Isaiah 24:21).

And on that day, the heavenly bodies — that is how ancient people viewed the moon and the sun, as part of the heavenly realm; the heavens will be dismayed and ashamed for this rebellion, and the Lord will reign from his throne. Remember this was in the Temple, on the ark, in Jerusalem (that’s how God is described dwelling in the temple “reigning between the Cherubim”), and in heaven. He will reign before the elders (Isaiah 24:23). This is not definitively heavenly or earthly, and in some ways it could be both — it is just that humans will come later in the piece in John’s vision. But, again, these elders are looking at the one on the throne. And that should be our focus. Not the weird beasties or the heavenly dancing Presbyterians, and not, in this next bit, the things in the hands of the people on the throne; the scrolls and seals.

The lens is pointed at the throne.

If we look at the other weird bits and worry about the scary stuff that worry can consume us and distract us, and remove our confidence in the one ruling on the throne. John’s lens wants to keep drawing our attention to him.

These heavenly characters are not just circling God’s throne, but the slain lamb standing at the center of the throne (Revelation 5:6); the one who sends God’s spirit into the earth; God’s life giving, glorious, presence.

The Lamb takes a scroll from the one on the throne — God, and when he takes it the elders fall before him in worship. They make us look at Jesus again. These heavenly elders are God’s servants, John also sees them serving God, before the throne, holding on to the prayers of God’s people; bringing the people of God into the presence of God (Revelation 5:8). And it is not the contents of the scroll they draw our focus to — but the worthiness of the lamb who was slain who by his blood purchased people for God from every tribe and language and people and nation (Revelation 5:9).

And made them one kingdom — a kingdom of priests who will reign on the Earth, the way Jesus is now reigning in the heavens (Revelation 5:10). The King of Kings who rules over the powers and principalities has brought people from all sorts of other kingdoms into his own kingdom of priests.

The heavenly host expands — 100 million angels join in song — praising the lamb (Revelation 5:11-12). The King. The one who was slain and is now worthy to be worshipped; to be honored, glorified, and praised in song. And then we get the super wide shot — each transition the lens is expanding to include more people and creatures — from the center — the throne — outwards; from the one on the throne to every creature in heaven and earth glorifying both the one who sits on the throne and the lamb (Revelation 5:13).

Whatever you want to make of the next bit — the opening of the scroll in chapters 6 and 7 — we are meant to know that God and the slain lamb are in control. They are ruling over what comes next.

So when the scroll is opened and the four horsemen of the apocalypse trot out in Revelation 6, they are not sinister figures opposed to God, but the ones who bring his judgment — the day of the Lord — anticipated by the prophets, and even earlier, in the law. All the plagues and pestilence and destruction the horsemen bring are the punishments promised by God for people who turn their backs on him and worship false gods in Leviticus.

The first rider brings the sword; turning people against each other; leaving us playing the game of thrones, dominating people to get what we want, like we are all caught up in a squid game (Leviticus 26:17).

The second horseman — the black horse — is a picture of economic destruction; inflation, the land working against people, scarcity, and no bread (Leviticus 26:26).

Then it is the pale horse — death and hades — bringing death; even through attacks from wild beasts (Leviticus 26:22). This is where beastly worship leads. He also brings the sword, wars, and plagues (Leviticus 26:25). There is a reminder of Egypt here too, and this is a picture of judgment, exile from Eden; curse; for breaking relationship with God.

This is Jesus bringing the day of the Lord promised by the prophets. This lines up with Jesus’ proclaiming judgment on Jerusalem as he approaches the cross, and his promise that the temple will be destroyed and God’s kingdom removed and given to others; a picture he, and John, both drew from Leviticus, Isaiah and Ezekiel (Ezekiel 9:2).

When Israel experiences this exile from God’s presence, when the sword is unleashed, in that moment, in Ezekiel, the cherubim, who had been gatekeepers of God’s glorious presence in the temple, they move from the Holy of Holies to the threshold, and some guys with swords turn up. God sends this bloke with a writing kit along with the sword guys (Ezekiel 9:2-3). His job is to mark out God’s people — like at the Passover — to spare them from the judgment that is about to be dished out. Those with this mark on their foreheads will be protected (Ezekiel 9:4). This is a new Passover, only it is happening in Jerusalem — and it is imagery we see in Revelation too. Once that judgment is carried out, Ezekiel pictures God and his gatekeepers, the cherubim, taking off; departing (Ezekiel 10:18-19).

Exile was the beginning of God’s judgment on religious and political Israel for not being his priestly kingdom — a judgment finally sealed for them when its leaders kill Jesus, and the curtain tears.

John is showing how exile in Babylon – for Israel — was just a shadow of the exile that comes when you kill God’s lamb, which comes on all the nations.

I know this is a lot.

So let’s just take stock.

In the Old Testament the Cherubim and Seraphim were heavenly beings — like the elders — powers and principalities. The Bible depicts them as the sort of beastly figures worshipped by the nations — and condemns Israel, in particular, for worshipping these beastly gods rather than the God they serve — the Lord of Hosts.

These divine creatures though, they were gatekeepers of God’s presence. They kept people out. Out of Eden, out of the Holy of Holies. And when the exile happened — when judgment came on Israel — they took off with God.

Now, in the New Testament, John is using all this same imagery to say the same judgment that came on Israel in the Old Testament is — like the prophets anticipated — about to come on Jerusalem and the nations.

Jesus, the slain lamb, has won a victory over the powers and principalities, which means the nations, and the spiritual realm, are now called to worship Jesus as king. He is creating a kingdom of priests from all nations, not just Israel, by inviting people to come out of those nations — to be marked by him — rather than the beast — and so to be saved from God’s judgment. Because when Jesus — the slain lamb — comes as judge, and unleashes God’s promised consequences — that bit in Isaiah is fulfilled — all the kings, the princes, their mighty armies and the powerful economies that sustain them — everyone not marked for life, they face the terrifying prospect of realizing they have stood against God and his king (Revelation 6:15).

And it is terrible. They do not want to see God’s face, or feel his wrath.

In Revelation this judgment — this Passover — does not just fall on Israel. It is coming for all people, and those who are marked by the lamb, rather than marked by the beast, will live in God’s presence (Revelation 6:16-17).

Exile from God’s presence or Exodus to be made a kingdom of priests. Beast or Beauty. Those are the choices.

This is the lens we are given — the lens is often on the horses and horsemen, and the punishments, and trying to figure out where we are in history, rather than on the one who unleashed them, and how we should respond.

Then the lens points at people.

Suddenly the cherubim are not keeping people away from God’s glory — people are now joining their song. First the 144,000 (Revelation 7:4). Now. Lots has been said about this, lots of people have guessed what is going on — but I think it is a picture of a restored Israel — Israelites who put their trust in Jesus — not a literal number that has to be filled up, but multiples of 12 as a picture of completeness.

This is not all the people who are saved ever. It is not those of us who are gentiles — also saved and marked by the lamb, because we come next.

This is the bad stuff in the Old Testament coming untrue; the exile of Israel, the destruction of a bunch of the tribes, and the exile of the nations and us all being handed over to other powers, and humanity’s exclusion from Eden; from life with God.

Now, all humans everywhere are invited to be God’s glorious people again; to become part of this great multitude from every nation, tribe, people, and language, standing before the Lamb (Revelation 7:9).

Calling out:

“Salvation belongs to our God, who sits on the throne, and to the Lamb.” (Revelation 7:10).

We are invited to look at the throne and join the chorus of heaven; worshipping God as one (Revelation 7:11). This great multitude is the people saved by the blood of the lamb — like in the Passover — washed, cleansed, glorified — marked as his (Revelation 7:14).

We are invited to join in; to be saved by the Lamb, to no longer be separated from God by swords and judgment, but be brought into the presence of God — back into the place sealed off by the cherubim — whether at the gateway of Eden, or the curtain temple. Our exile is over (Revelation 7:15).

We now enjoy blessing — covenant blessing — rather than those Leviticus curses for false worship (Revelation 7:16), being led by the Lamb, as our shepherd, to living water and a world beyond curse — there is a nod here to the new creation pictured at the end of the book (Revelation 7:17).

John sees things Old Testament anticipates like the choice between exile from God, or restoration through God’s anointed king in a new Passover; or between death separated from God’s presence, and life in the new Eden, a restored creation — centered on the lamb.

John invites us to share his vision of the throne room, and to choose the throne we serve.

We might not have beastly gods. We might not worship spiritual powers and principalities — heavenly beings who actually rightly serve God. We might not even have categories for cherubim and seraphim.

We might not have a tyrant on the throne — like Nero — a beastly ruler who killed his own mother to hold his throne; who commanded citizens of his empire worship him and his ascended ancestors.

But we face the same temptations that people pulled to beastly worship by the imperial cult faced.

This was a significant pressure in the world Revelation was written to. My old college principal, Bruce Winter, wrote a book Divine Honours for the Caesars, about how pressure from the Roman imperial cult was profound for early Christians, and how this pressure was not just the sword. It was cultural. The beastly empire of Rome had a beastly violence at its heart.

Emperor worship was propped up by blood. He wrote:

“Imperial veneration was also combined with other public activities, including spectacles such as gladiatorial and wild beast shows, athletics, chariot races and public feasts, such was its assimilation into the life of cities in the Roman Empire.”

Beastliness was embedded into the religion, the politics, the economy, and the entertainment and culture. It formed the imagination of the people.

So what sort of thrones shape your imagination?

Probably not Game of Thrones — but almost certainly the world it tried to unveil — a world where might makes right and violence solves problems; a world where entertainment is embedded in the same system it sometimes tries to critique, so we are never sure if we are escaping it, or escaping to it.

These systems are so compelling — just like Rome’s culture of games and feasts — that even critiques of the system become part of the system; things that feed our hearts, but also make the people making the critiques stacks of money. It is a vicious — beastly — cycle.

And the solution — the solution offered by Revelation — is not more escapism into beastly throne rooms, or onto your couch where you join in glorying in violence and cultivate desires that pull you from Jesus.

It is to keep our eyes fixed on Jesus, the Lamb at the center of the throne of heaven (Revelation 7:17); to worship him as king; to find ourselves deeply embedded in his story, having our view of the world shaped by gazing upon him. The challenge is to fill our eyes — and our vision — with this throne room. This king. This kingdom. Rather than having our hearts shaped by the beastly world around us. That does not mean not watching super violent shows, or the art or entertainment from the world, but it should prime us to see critiques and push for change; rather than reveling in the violence and misery.

We should be moved to want more of God’s kingdom to come when we are confronted with the stark reality of the kingdoms of this world.

But it does mean not just watching the world through the lenses it provides.

It means not being caught up in beastly regimes through bread and circuses.

It means finding things — the Bible, art, people who live in ways led by the Spirit — that centre your life on the throne; and finding ways to feast on those things so we keep our eyes on the Lamb.

One way I do this — and we do this as a family — is with the Bible Project. Their videos are fantastic — they love the big story of the Bible — our kids love watching Bible Project with us.

But they have also got a podcast that sometimes moves me to tears as it keeps me finding new ways to see the glory of Jesus and the wonderful intricacy of the Bible’s story. They have fantastic content on Revelation. So does the Naked Bible podcast. It gives me fresh eyes as I am engaging with God’s word, and it is full of rich stuff on Revelation going at a much slower pace than we are.

We also train our hearts as we sing like they do in the throne room — singing words joining the chorus of heaven. All the songs we sing are on a Spotify playlist so you can soak in them, sing them in the shower — do whatever it takes to focus in on the Lamb.

And of course, we are about to share in the feast of the Lamb together — the picture of a new Passover — that marks us out as Jesus’ priestly kingdom [note, we share communion together every week after the sermon].