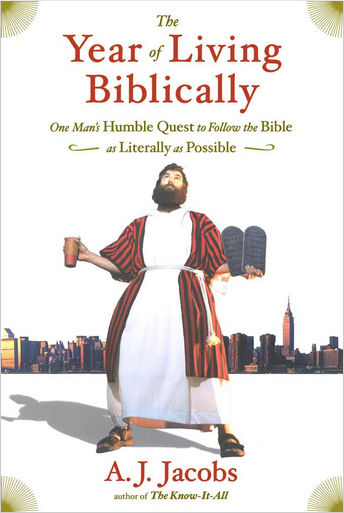

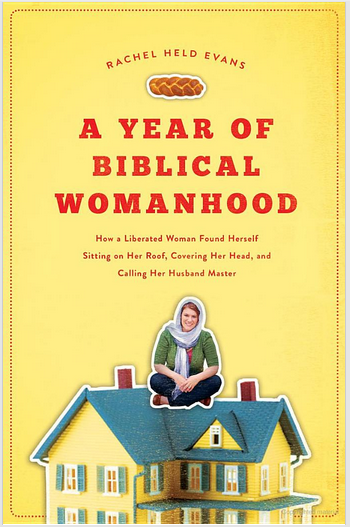

I read The Year of Living Biblically: One Man’s Humble Quest to Follow the Bible as Literally as Possible last year. I think I meant to review it. But I forgot. Now, Rachel Held Evans, a Christian blogger, has set the blogosphere atwitter with her A Year of Biblical Womanhood: How a Liberated Woman Found Herself Sitting on Her Roof, Covering Her Head, and Calling Her Husband “Master”

The two are essentially related.

Here’s the YouTube trailer…

And a TED talk author AJ Jacobs gave on the experience.

Despite a bunch of hermeneutical problems – I really enjoyed his book – it was well written, honest, and good humoured. It wasn’t a great picture of what Christianity is – which is particularly fair enough, given that Jacobs is a secular Jew. You can’t necessarily expect him to have a good grasp of a hermeneutic that incorporates the New Testament.

He had this idea that taking the Bible “literally” and taking it to its logical conclusion meant “taking the Bible literally, without picking and choosing”… he was inspired by his “crazy ex-uncle,” Gil.

He started out by writing down every single law that he could find in a couple of readings of the Bible, then set out to apply them as literally as possible. Though he gave himself some wiggle room right from the start:

“I will try to find the original intent of the Biblical rule or teaching, and follow that to the letter. If the passage is unquestionably figurative – and I’m going to say the eunuch one [Matt 19:12] is – then I won’t obey it literally.”

He gave eight months to the Old Testament, and four to the new – which is generous, because as a Jew he could’ve been consistent and just stuck with the Old.

He says in the TED video that he was amazed by how his behaviour changed his thoughts – rather than his mind changing his behaviour. Which is an interesting insight.

It’s a pretty interesting read, it’s thought provoking, it’s full of great stories that will become good sermon illustrations of his meetings with various people, including a group who are dedicated to breeding unblemished red cows for the purpose of sacrifice once the temple is restored in Jerusalem.

He asked some really honest questions of the Bible, and was honest about how it impacted, and didn’t impact, his life. He ended the year as a “reverent agnostic” who thinks that there’s something important about sacred stuff.

One of his big take home lessons was “though shalt not take the Bible literally,” which is interesting. But very few Christians do what he suggests is the “literal” reading of the Bible. Because the Old Testament is changed by the New Testament. It’s a fun game – but Christians should know better. Shouldn’t they?

Now, I’m not going to suggest that all Christians read the Old Testament well – there are plenty of people who draw weird allegorical interpretations from the Old Testament, or who don’t mind the gap, and take the promises of prosperity that are time and place bound – to Israel, in the land, and apply them to life now. That’s a real problem in many circles that take the Bible seriously. As is reading any Biblical text – from the Old or New Testament – “literally” – taking text at face value without considering context, genre, and what the original meaning might have been.

So there’s a legitimacy to critiquing that approach to reading the Bible – and I think that’s where I’m prepared to cut Rachel Held Evans, author of A Year of Biblical Womanhood some slack that others aren’t.

She isn’t doing the hermeneutical work (hermeneutics = principles of interpretation) that she should, as a Christian, be doing – but precisely in not doing it, she’s making a point about some other approaches to the Biblical text. She’s made some people, like Kathy Keller, a little bit upset in doing so. On one level, Keller has missed the point. But on another, she’s right – Held Evans has been on the media circuit promoting this book, using an almost identical rationale to Jacobs, who’s a Jew. Held Evans is a Christian.

We should, I think, expect Christians to have a better grasp of the Bible, and speak from that point of view, most times, lest they undermine the most consistent way to read it – which is as a grand, unfolding, narrative of God’s plan for salvation in Jesus – that’s why we keep the Old Testament, without jettisoning the superseded laws.

This exercise would be problematic if Held Evans is making an in-house point, that is being lost in media coverage of her book. The reception has certainly focused on the controversy and reaction to her book – here are two examples from an American Newspaper I’ve never heard of, and Slate who focus on some controversy surrounding Held Evans using the word vagina in the book – which means some Christian book stores won’t sell it. But most people seem to be getting the joke. Most secular media outlets understand that she’s not applying a hermeneutic she agrees with. The Huffington Post ran these pieces that recognised Held Evan’s point (and this one). It seems most of the in-house furore is from people who don’t get that Held Evans “literal approach” is ironic, or don’t think she should be being ironic. Which is a shame. But there are plenty of readers who won’t get the irony either. This review seems to suggest that because not all evangelicals read the Bible like Held Evans is demonstrating, her being ironic is not enlightened, but adds fuel to the fire.

Evans writes,

The Bible isn’t an answer book. It isn’t a self-help manual. It isn’t a flat, perspicuous list of rules and regulations that we can interpret objectively and apply unilaterally to our lives. (294)

And yet, amazingly, scripture is clear enough to Evans that she can determine it has been misread and misapplied by the evangelicals who advocate for a biblical view of manhood and womanhood.

That review, like Keller’s, provides a pretty stellar overview of a consistent way to read the Bible and create a category of Biblical womanhood, but the fact that pages like this one, about Proverbs 31 “Christian mom/entrepreneurs,” and that some of the books featured in this post, exist is a testimony to part of the problem Held Evans seems to be engaging with.

Keller calls Held Evans out for “picking and choosing” – an echo of one of Jacobs’ conclusions to his experiment – that one needs to “pick and choose” if they’re going to live Biblically in modern life.

Here’s what Keller says:

Yet you, who surely know this as well as anyone, proclaimed at the start of your book: “From the Old Testament to the New Testament, from Genesis to Revelation, from the Levitical code to the letters of Paul, there [will be] no picking and choosing” (xvii, emphasis mine). To insist that it would be “picking and choosing” to preclude the Levitical code from your practice of biblical womanhood is disingenuous, if not outright deceptive.

In making the decision to ignore the tectonic shift that occurred when Jesus came, you have led your readers not into a better understanding of biblical interpretation, but into a worse one. Christians don’t arbitrarily ignore the Levitical code—they see it as wonderfully fulfilled in Jesus. In him, we are now clean before God. I doubt if you had given birth during this year you would have made a sin offering after your period of uncleanness (Lev. 12:6-7). I doubt this because you know that in Jesus the sacrifices, as well as the clean laws, are fulfilled and therefore obsolete.

She’s right. Christians shouldn’t “pick and choose” – we should read the Bible through the lens of Jesus – but that doesn’t always happen. And I suspect that’s the point Held Evans, if not Jacobs, is making. Jacobs isn’t ignorant of other hermeneutics either – he spends time with Christians of different denominational ilks in his experiment. He hangs out with snake handlers – and acknowledges that most Christians are able to distinguish a disputed verse in Mark as being descriptive, rather than prescriptive, so that we don’t go picking up poisonous snakes every Sunday morning…

Keller makes the point in her review that there are times that Held Evans isn’t as generous to the writers of the Bible as Jacobs was – there are a couple of points where she misattributes views that Paul is quoting to Paul himself, or applies something in a humourous and literal way when it’s clearly figurative. But again, I’m willing to cut Held Evans some slack, because if, at the heart of her premise, is the idea that other people pick and choose how they read the Bible, then she’s right – and her point is well made. Bad readings of the Bible that are inconsistent, and bring bizarre modern hermeneutical gymnastics to the table, produce bad results.

I’m with Keller though – I think the best results, and the best hermeneutical method, involves thinking about how a passage relates to the Lordship of Jesus, and passages should be interpreted as products of their time, place, purpose, and genre – before making any jumps to the present.

Here’s how Keller rounds out her review…

“Rachel, I can and do agree with much of what you say in your book regarding the ways in which either poor biblical interpretation or patriarchal customs have sinfully oppressed women. I would join you in exposing churches, books, teachers, and leaders who have imposed a human agenda on the Bible. However, you have become what you claim to despise; you have imposed your own agenda on Scripture in order to advance your own goals. In doing so, you have further muddied the waters of biblical interpretation instead of bringing any clarity to the task.”

The question is, is this judgment warranted. Does A Year of Biblical Womanhood muddy the waters?

Most Christian readers I know won’t find her titular definition of “Biblical Womanhood” particularly resonates with their experience. Robyn just told me if I told her to call me master she’d laugh, and if I was serious she doesn’t know what she’d do. We’ve been married five years, and the issue has never come up before. But it’s not really written for me. It’s written for people across a much broader spectrum of Christianity than Held Evan’s fellow evangelicals, perhaps even feminist non-Christians.

Much like Jacobs’ work, A Year of Biblical Womanhood is an enjoyable read – it’s funny. It’s occasionally poignant. Whether Held Evans is sitting on a roof, in contrition, trying to cook like Martha Stewart, or calling her husband “master” – there’s something to savour, and get annoyed by, and be challenged by, in every chapter. It’s frustrating. It’ll no doubt mislead some people. But it makes a serious point about wrong ways to read the Bible. And for all the frustations I felt at Held Evans misrepresenting the “evangelical” line that I’m familiar with – she grounded her accusations in reality, she talks about a group dedicated to the Biblical concept of patriarchy, and some “biblical polygamists.” Her criticisms might be of extreme groups, taking extreme positions – but they’re not so absurd that they don’t exist.

Like Jacobs, Held Evans doesn’t give a great answer for how to read the Bible, running the we have to “pick and choose” line – but it goes closer. Here’s what she says:

“Philosopher Peter Rollins has said, “By acknowledging that all our readings [of Scripture] are located in a cultural context and have certain prejudices, we understand that engaging with the Bible can never mean that we simply extract meaning from it, but also that we read meaning into it. In being faithful to the text we must move away from the naïve attempt to read it from some neutral, heavenly height and we must attempt to read it as one who has been born of God and thus born of love: for that is the prejudice of God. Here the ideal of scripture reading as a type of scientific objectivity is replaced by an approach that creatively interprets with love.”

For those who count the Bible as sacred, interpretation is not a matter of whether to pick and choose, but how to pick and choose. We are all selective. We all wrestle with how to interpret and apply the Bible to our lives. We all go to the text looking for something, and we all have a tendency to find it.”

Like Keller, I think this is fairly weak. I think we can approach scripture with an essentially “scientific objectivity” through historio-critical hermeneutics that have been demonstrably popular, at the very least, since Calvin, Luther, and Erasmus (basically since humanism), and with various figures throughout church history before that, with varying degrees of consistency. The criticism that we each bring an agenda to the text doesn’t warrant coming up with a blanket interpretive rule that we have to shoe-horn every text into, it means being careful to treat every text on merit, using a consistent method. But more than that – I think “love” is objective too – not a subjective thing that requires creativity. The Bible reveals God’s love to us in Jesus, from start to finish. We interpret a passage with justice when we realise that the Old Testament laws, and prophets, are fulfilled in Jesus – even if it’s true that the Old Testament laws should originally have been interpreted through the lens of “love the Lord your God with all your heart” and “love your neighbour as yourself” – and a Christian ethic should do the same – if Biblical interpretation isn’t dealing with the question of how Jesus changes things – it’s not truly “Biblical” – that’s the criteria by which most readings fail.

The real strength of her critique is in the power of the negative:

“Now, we evangelicals have a nasty habit of throwing the word biblical around like it’s Martin Luther’s middle name. We especially like to stick it in front of other loaded words, like economics, sexuality, politics, and marriage to create the impression that God has definitive opinions about such things, opinions that just so happen to correspond with our own. Despite insistent claims that we don’t “pick and choose” what parts of the Bible we take seriously, using the word biblical prescriptively like this almost always involves selectivity.”

She’s right. Most of us selectively read the Bible. Most of the time. We all have a tendency to want God on our side – supporting our football team, cause, or institution – and I’d argue that there’s an objectively right answer in most of these cases, but a lack of wisdom, ability to make complex decisions with omnipotent clarity, and the effect of sin means we’re all equally unlikely to land on it.

Her methodology is very similar to Jacobs’, only less charitable.

“This quest of mine required that I study every passage of Scripture that relates to women and learn how women around the world interpret and apply these passages to their lives. In addition, I would attempt to follow as many of the Bible’s teachings regarding women as possible in my day-to-day life, sometimes taking them to their literal extreme.”

For me, one of the interesting parts of the book is the way the online conversation on her blog, about the process of writing the book, becomes part of the book itself. There’s something meta about that that I appreciate, the commentary becomes the content. The conversation is about the conversation.

By this point I’d been reminded about a million times that the Bible didn’t explicitly command contentious women to sit on their roofs, and that rooftops in the ancient Near East would have been flat and habitable anyway, but I was determined to engage in some kind of public display of contrition for my verbal misdeeds… I spent an hour and twenty-nine minutes on the safest corner of our roof, reading over my list of transgressions, practicing a bit of centering prayer, and watching a small herd of cats mill about the neighborhood.

My biggest frustration with Held Evans’ exegesis of narrative came in her discussion of polygamy – where she makes the blanket claim that the Bible assumes, rather than condemning, polygamy. I don’t think that’s a particularly sensitive reading of any of the New Testament passages about marriage that either assume a marriage is between a man and a woman (so Jesus in Matthew, Paul in Corinthians), and the qualifications of an elder state that the leaders of churches are to be the husband of one wife (1 Timothy, Titus). But the biggest grievance here is that it’s a poor reading of the Old Testament narrative – especially as she holds Solomon up as a Biblical hero – when his propensity for marriage was what caused the end of Israel and the spiralling into exile…

I’m as complementarian as they come – I’m ok with gender forming a different flavour of identity for men and women, and want to affirm, lovingly, and with equal value when it comes to personhood, the distinction between genders. My reading of the Bible resonates with Keller’s, and Flashing (who wrote the second review I linked to), rather than Held Evan’s slightly more post-modern approach to the text, and I’m pretty convinced we’ve got it right – but that’s not a reason not to criticise readings that we all think are wrong – readings that don’t pay attention to the context – which we’re all trying to do, just with different results, and thus, different conclusions. So I’d recommend the book – it’s funny, it’s interesting, it makes some strong points against those it critiques – but I’d not recommend the conclusion – which replaces Jesus as the hermeneutical key with “love,” when surely it’s the love of Jesus that gives all people the most hope, and a life lived following King Jesus is surely the most biblical type of life.