This is an adaptation of the eighth talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, or watch it on video. It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

We have covered a lot of ground this series. We have looked at many of the ways we are being disintegrated as humans; pulled apart because we are pulled in so many directions all at once; we are bombarded with images in the spaces we occupy, in ways that shape our desires; our technology allows us to overcome the limits of our bodies, and there are narratives telling us the best thing we could do is leave our bodies behind and become immortal by making ourselves one with the cloud.

We have seen how there is a real sense that as we have shifted from Christendom, where there was a shared story about the world — where God was God, and the King and Queen were the rulers, and everyone knew their place, and you did not change — to a modern liberal democracy, where we are free from forces beyond ourselves; and we have closed ourselves off to those forces, and to the supernatural — in the West. How we now prefer to express ourselves and be authentic as an expression of this liberation. We saw how this means we have lost a great narrative; a story that unites us as humans — to each other, and to God. And this also meant moving away from communion with God — the triune God who is a community of love — being how we understand what it means to be human. We have now become authorities — self-authors of our own lives.

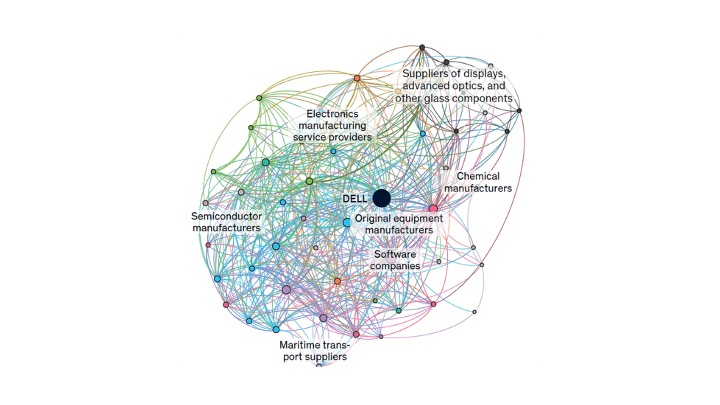

We saw how the world has become not just complicated, but complex.

We are caught in global webs and supply chains we do not understand. We have seen how our technology shapes our brains — through dopamine hits and how this is been co-opted by limbic capitalism — and how what we see is shaped by the algorithms of surveillance capitalism; to sell us stuff based on our desires and addictions and patterns of behaviour. If all this is true, it presents us with a challenge when it comes to knowing what is true — and being able to tell when we are freely acting as individuals — who are meant to be free from powers outside ourselves, and free to express ourselves. How do we know if we are expressing our own desires, or the desires implanted in our head by the machine world?

When we talk about these unseen forces shaping our thinking so we will use our bodies, and our energy, and our money in service of their kingdoms — while telling us we are free — this is what the beastly powers and principalities the Bible talks about look like in the real world. This is how — in Paul’s words in Ephesians 2, we are dead, captivated to fleshly desires, and under the power of the prince of the air. Being truly human is about being liberated from the serpent’s coils, and his lies (Ephesians 2:1-3).

Part of the disintegration happening to our humanity — and perhaps our own individual experience — involves our inability to know what is true because we are not just bombarded with images of the good life that fire up our desires, but with competing ideas about what is true. And if the systems we plug into and play with are not just geared to shape our desires, our beliefs and our thoughts through ‘scripted disorientation’ in ways we cannot see, we are going to find it tricky to know what truth is. This makes the task of building one another up “speaking the truth in love” or literally “truthing in love,” difficult, and makes it likely that, instead, we will be swept all over the place; ‘blown here and there’ (Ephesians 4:14-15).

So as we start tying up these threads — looking at the world that is disintegrating us — I want to suggest that we are made to be integrated; that we are made to be whole; joined up; connected — one — integrated in body, mind, and soul — sure, but also integrated into community — with other people — in the body of Jesus as our reading describes us and united — one — with God. This is the key to being truly human and holding it all together; and what has happened with all the social change we have covered is that these integrities have been pulled apart — because we — together and as individuals — live lives in the world that believe the lie of the serpent.

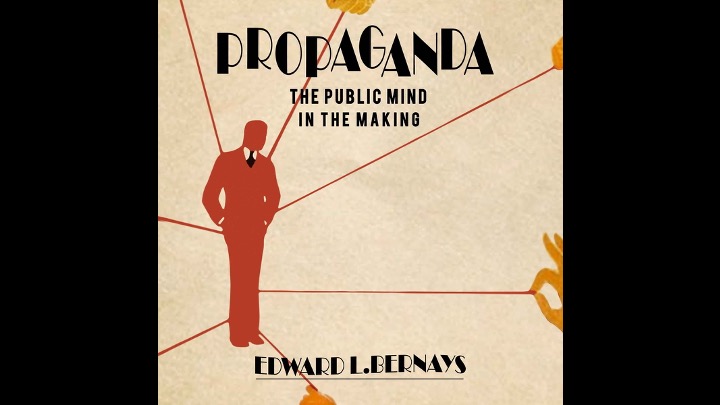

This is especially challenging in our age of digital propaganda — empires have always used imagery to enforce beliefs in truths within their system — Israel had the temple and sacrificial systems and its ritual life, Babylon had its stories and idols, Rome had its temples and statues and stories and spectacle — but in the 20th century a guy named Edward Bernays — Freud’s nephew — drew on his uncle’s insights and applied them to public persuasion — in his book Propaganda.

It was a popular book in the image management project for the Nazis in Germany — but it is also a handbook for modern politics, advertising, and “public relations” — you might know that is the field I worked in before ministry.

In his book’s opening paragraph Bernays says the manipulation of our habits and opinions is foundational to democratic society.

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organised habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.”

Edward Bernays

While we feel free, it is like we are caught in a web by these spider-men who spin their lines so:

“We are governed, our minds are molded, our tastes formed, our ideas suggested, largely by men we have never heard of.”

Bernays

And these spider-men — not the friendly neighbourhood variety — are the true ruling power in our societies.

“Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.”

Bernays

There has also been a massive increase in what the academic Harry Frankfurt called bull**** (note, I didn’t use this word when preaching, I called it ‘bullpoo’) — a technical description of deceptive speech that is not outright lies, but does not bother trying to be true.

Frankfurt reckons we are surrounded by spin, by misrepresentation, by bull****, which he says is a type of speech “… unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about…”

He suggests it arises from “the widespread conviction that it is the responsibility of a citizen in a democracy to have opinions about everything, or at least everything that pertains to the conduct of his country’s affairs.”

He has just described Twitter (now X); but also the animating forces of fake news and troll machines and the outrage industry, and the spiders spinning political speech who cannot speak straight sentences but use what George Orwell called doublespeak.

Like surveillance capitalism, and limbic capitalism, these propaganda machines are unseen forces manipulating and shaping our beliefs by spinning webs of half truths — the powers and principalities in our world propping up empires built on spin and idolatry and deception and that bull****.

If these forces are at work in our world how can we know what is true? How can we live truly? Especially if it is all fragmented and now there are multiple spiders spinning multiple webs — all offering their own truths according to our interests — like in a democracy — there is a reason people say we live in a post-truth world. Part of the shift away from God has involved separating big-T truths — facts — about earth from our spiritual values — personal little-t ‘truths’.

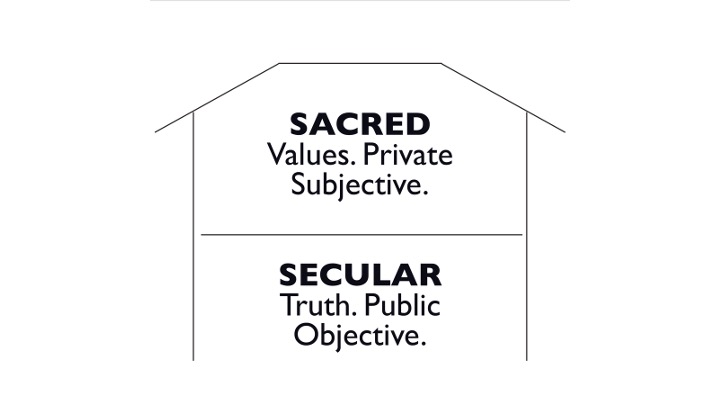

The author Nancy Pearcey borrows a picture from Francis Schaeffer of a two-storey (and two-story, pun intended) house to describe this shift and the way it plays out on modern questions of truth about our bodies, and our lives — in this metaphorical house, empirical objective truth — the scientific realm — is one storey, the facts, that shape public life, and beliefs about God falling into the subjective storey of private beliefs — values — where what is true for you is not true for me.

But what if those areas — morality and theology — are areas where there is actually capital-T truth that should shape not just our lives, but society?

And — to be fair — part of what led to this fragmenting was a lack of integrity on the church’s part — historically, with the corruption that prompted the Reformation. The Reformation created multiple ways to be Christian; it made multiple truths imaginable in Christendom — but it is happening presently too, where the church, which is meant to teach us truth, has acted like the powers and principalities — using our power to abuse and force people to conform while claiming to represent the capital-T Truth — and then employing spin and propaganda and cover-ups — people have inevitably — as they have walked away from those abusive institutions — walked away from the truths they proclaimed.

This has led a bunch of folks my age and younger towards deconstruction. This might be where you are at — right now. Now — I am all for deconstruction when we are deconstructing falsehoods and abuses in the church — both church traditions here are children of the Reformation; and I am all for recognising the way abusive institutions have caused wounds that intersect in damaging ways with the truths we have been taught by those institutions — and I recognise at times it can be super tricky to separate God from the church… but our deconstruction also has to extend to the powers and principalities corrupting the church — to seeing if these behaviours are true — if they are godly — and the risk with deconstruction is where we find ourselves “did God really say” and being drawn by those same powers to grasp onto things God says are bad for us. Deconstruction will only get you so far — it becomes disintegrating and destructive without reconstruction being part of the picture; without some sense that truth exists and that to be fully human is to live a life of integrity — one that is true.

If we want to be truly human — well, our origin story has something to say here — not just Genesis — but the Gospel — and Ephesians 2-4 (the Bible reading for the sermon) — unpacks what it looks like to find our life in that story, rather than the propaganda pulling us back into the serpent’s coils.

We do not live in a two-storey universe where there are facts related to the material world and values related to the spiritual side of life; if the same God is the creator of heavens and earth then — sure — there are two storeys — but there are truths in each; that we split them is a product of a disenchanted world where we get rid of the heavens and spiritual thinking, and see it having no bearing on reality.

And then ultimately we see that the Bible tells one story of the two storeys being brought together. Jesus turns up to end the exile — from Eden and Israel — as the tabernacle-in-the-flesh who brings heaven on earth — who comes to save us from homeless life in non-places — and he does not do this by restoring the temple to its former glory — as heavenly space — you might remember as we worked through Matthew’s Gospel that our origin story — the Gospel — is the story of heaven and earth coming together as the heavenly human brings the kingdom of God. To be truly human is to get our facts straight about heavenly life; about God and who he created us to be as we reflect heaven on earth as his image-bearing people.

We also live in a two-story world — in the narrative sense — we are either living in God’s story, or the serpent’s. The serpent was the first creature to introduce uncertainty about facts when it came to the upper storey — the heavenly realm — he got humans questioning ‘did God really say’ — questioning ‘is God really good’ (Genesis 3:1). He was a propagandist… putting the ‘pagan’ in pro—pagan—da. And since that lie worked so well he has been using this same deception to devour others. To disintegrate us — using powers and principalities — elemental forces — to shape the world and so shape our beliefs.

Humans became captives to deception — to deceptive idolatrous systems that harden our hearts into stone — like the people of Judah (Jeremiah 17:1). Idols and sin rewrite and rewire so that our hearts are “deceitful above all things” and “beyond cure” (Jeremiah 17:9). We need new hearts — with truth written on them by God, rather than idolatry inscribed on them by us — so we will see what is true (Jeremiah 31:33).

Which is what Jesus came to bring — the Word of God from the beginning — God tabernacling in the world (John 1:1, 14), as he came to liberate us from the father of lies — the devil — and those — like the Pharisees — who would build systems of deception to pull people away from God (John 8:44-45). Jesus used his “I am” statements through John to identify himself with the God who created the world and he describes himself as the way, the truth, and the life — the one in whom both storeys — the heavenly or spiritual — and the material — are held together and expressed as one integrated truth (John 14:6-7). And he calls us to find life in him — and John says he writes so that we might believe this true human is the path to true life (John 20:31).

So that we might — as Jesus puts it — find life in oneness with the triune God, being drawn into the eternal communion of love — through him (John 17:20-21),

as he provides hearts that point us to the truth by giving us the Spirit — the Spirit of truth (John 14:16-17, 16:13).

What is interesting in John — given the way he sets up deception as devilish and truth as found in Jesus — is how he reports Pilate’s words at Jesus’ trial — here Jesus is up against the face of the bull machine — Rome — in Jerusalem; the deceptive idolatrous regime that claims to be bringing heaven on earth, and is full of spin — and Pilate looks at Jesus, who claims to be king — not Caesar — and that is the charge against him — Jesus says he has come on the side of truth; to testify to the truth, that everyone who listens to truth — two-storey truth — listens to him (John 18:37), and Pilate says “what is truth” (John 18:38)?

We are all Pilates now…

Pilate does not recognise truth when it is standing in front of him. He becomes wrapped up in the serpent’s schemes, and the schemes of his children: the Pharisees. Jesus is executed. And in that moment — as the serpent strikes his heel, the serpent is crushed (Genesis 3:16); his grasp on humans — built through deception — comes unravelled as he is exposed; and as God’s nature — his love — is exposed for those who can see the truth — we were dead — in our sins — following the serpent’s story (Ephesians 2:1-2), but now, God who is rich in mercy has made us alive… by grace (Ephesians 2:4-5).

If you sit here and you are convinced by the evils of a world built on deception and manipulation and what that does to our humanity in a world where we have walked away from God — that is the serpent — that is the same force at work in the world that is exposed as a deceived world kills God’s son. Come out. Believe the truth. If you are tempted to deconstruct, or disintegrate — to proclaim one truth and live another — come back to Jesus. Away from death.

Not only is the serpent diabolical — literally — God is good and loving and shows that in the way Jesus radically refuses to use his power to manipulate and deceive; to the length he goes to in order to not be coercive, so that he dies, humiliated, on a cross to make a way to life with God, and expose us to the truth about God.

Jesus — the way, the truth, and the life — offers the pathway to the integrated life of communion with God, and others, we were made for — and the path away from the deception of the serpent, and our deceitful serpent-like hearts. He reconstructs us.

Paul talks a couple of times in his letters about people having been bewitched — and enslaved — to the elemental spiritual forces of the world — who are opposed to Jesus (Galatians 3:1, 4:3). He talks about these forces built on hollow and deceptive philosophy, rather than on Jesus — the fullness of God in human form (Colossians 2:8-9). He says we died to those with Jesus, and so we should stop living by their scripts (Colossians 2:20). It is interesting that in both cases he is talking about people who want to operate as though we are under law creating rules as truths to live by — not grace — but there is a pattern where spiritual forces are being used to pull people away from truth. Away from oneness with Jesus.

In Ephesians 4 he describes what this looks like — what it looks like to be one with Jesus. One with each other. In communion — as one body and one Spirit (Ephesians 4:4-6). He describes a life grounding ourselves in the truth, and speaking it to each other — whether that is through particular speaking roles in church; or speaking to one another as the church — the goal is that we be established in the truth of the Gospel and united and mature in Christ, so that we are not infants tossed around by the deceitful scheming of people in the world who are serpent-like (Ephesians 4:11-14).

Paul’s antidote to a poisonous post-truth world hell-bent on our destruction is being people who “truth in love” — that is the literal translation — in the body of Christ — living integrated lives grounded in truth as we grow together… built up in love. This “truthing” in love certainly includes speaking the truth — because Paul is going to come back to that — we are to avoid lies — and, I would suggest — as much as possible propaganda and that bull (Ephesians 4:25).

Paul talks about the same heart-hardening that the Old Testament sees as a product of idolatry (Ephesians 4:17-18) — and that is part of the picture for us in a world where we are bombarded with lies and images that shape our hearts — so that we give ourselves over to greed and indulgence (Ephesians 4:19). Paul is describing their world — and ours.

But we are people who are committing to be taught in accordance with the truth that is in Jesus (Ephesians 4:20-21); putting off the selves shaped by deceit, that spin our webs of deceit even as we are caught in them — to become new people shaped by the truth, and committed to speaking it in a world of deceit as we become like God again, reflecting his righteousness and holiness (Ephesians 4:22-24).

And that is hard. Because deceit is hardwired into our world — and — without the Spirit — it is hardwired into our hearts. And we have to learn this. We have to learn to hear truth, and we have to learn to speak it — and speak it in a way that makes it plausible in our disenchanted two-storey world where this stuff is ‘value’ rather than fact — and where the institutional church has often been complicit in propaganda and that bull and abuse… and where we are formed to have — and voice — quick opinions about everything.

I am going to suggest two ways we might change how we approach truth, as people — how we work towards integration rather than disintegration — that will hopefully make us more likely to speak truth and less likely to spin that bull.

If what the Bible says — what Jesus says — not what the church says — if it is true, then Jesus is truth — and the truth about Jesus operates both in the material world — the world of facts — and the spiritual world — the world of values — in fact, he integrates the two; and so should we. We should reject the idea that we have a public and a private self — or that there is no truth — we are all going to pick a framework to work out truth from anyway; and none of us is free from powers beyond ourselves — so we are not losing anything if we choose to start with God — the creator — being the one who gets to declare what is true — and with Jesus’ claims that he is the way, the truth, and the life — and God in the flesh — as a starting point for assessing other truths.

I want to suggest the first real act of pursuing truth is contemplation — prayerful contemplation — the philosopher Hannah Arendt — whose intellectual project was trying to figure out how people in Germany came to believe the lies of the Nazis — she reckons we can only know truth; and live truly, if we stop moving and speaking — if we cease — if we be still and know that God is God. We have to free ourselves from the webs that entangle us.

“Every movement, the movements of body and soul as well as of speech and reasoning, must cease before truth. Truth, be it the ancient truth of Being or the Christian truth of the living God, can reveal itself only in complete human stillness.”

Hannah Arendt

Contemplating truth will mean listening to God — making headspace and time to engage with God’s word and pray that God’s living and active Spirit might guide us, through his living and active word, push us outside of the forces at work in our world against God, and towards God.

We will look more at this next week — but there is a trick to reading God’s word in conversation with other humans — within traditions that might need deconstructing — it is not always easy to separate our experience of people using the Bible without love, from the truth the Bible contains — and there is a whole internet industry geared towards deconstruction that basically sounds like people asking “did God really say”… but I reckon one guide is to read the Bible the way Jesus did — as one story — that testifies about him so that we receive Jesus as God’s truth.

True speech is actually going to require listening — to God — first of all — and to others — before we run around with our opinions. This sort of contemplation is not just an individual act — it is one we pursue as we engage in “truthing in love” together. I reckon the modern church is too geared towards actions and words — and online hot takes — that bull — without truth because we do not live contemplative lives.

Part of this contemplative life is going to involve cultivating the humility to recognise your limits; that your access to truth is limited by your brain, and your body, being stuck in a particular time and space — so you invite other people to speak the truth in love to you — and — as much as possible, receiving that truth without being defensive — this is something I am working on, personally — but if you are subjected to powers outside yourself, and told you are free — and that you have your own truth — you need someone to burst the bubble; we are not in a good position to be objective about ourselves, or the world — our standpoints, our experiences — the forces that have worked us over — we cannot see them, but others might be able to — especially older folks who have been through a bit — and older folks — I think I can still speak on behalf of the younger folks — we need you. But, there is a flipside where older folks might have been stuck in bad traditions so long a younger perspective can be helpful too — this is where the “in love” bit comes in to our truthing — so younger folks, let me embrace middle age and tell you we need you to speak truth to us older folks too; calling us to repent; to deconstruct and reconstruct our lives around the truth.

C. S. Lewis reckoned we should also listen to dead people — not in a spooky way — but by reading older books from outside our time — books from our time are a product of our standpoint, but in the words of older, dead, Christians we might find ideas that critique our take on the world.

“Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books.”

C.S Lewis, in his prologue to a translation of Athanasius ‘On the Incarnation’

In the olden days there were monastic folks who would withdraw from the city and go live in the desert — these desert mothers and fathers had a totally different perspective on their time — and the practices of the church — and listening to voices outside our experience; and outside the norm — might be part of proper humble contemplation. Read less white men. Listen to the people who are deconstructing because of the way the church has bought into lies, and contemplate how we are part of that picture as the church; the body of Jesus.

This contemplation might liberate us from forces we cannot see in our own time, and our own hearts — it might help us deconstruct lies in order to reconstruct our lives around truth. It might help us actually speak truthfully, rather than speaking that bull. We need that sort of truth in our lives.

The second practice is integration — it relates — but if we have this capital-T truth about God and humanity that truth should be true in every sphere and integrated into our lives and our actions and our other beliefs. It can be tempting in a world built on lies to embrace scepticism about all claims — but I wonder if integration — starting with a foundation — is a more hopeful posture — where, rather than being suspicious of voices that do not conform to our experience — our standpoint — we ask ourselves “how does this fit with what I know to be true because I know Jesus?” We are kind of perfectly positioned in how we are meeting together as two traditions to humbly recognise that different human traditions have limits; that there will be truths we have been blinded to by our traditions, and to humbly seek to reform and integrate those truths into our lives — our habits — and our beliefs as we seek truth together. Real truth is truth that is embedded into our lives — and a community — that is how “truthing in love” is about more than just words — but speaking truthfully to each other also requires the work of both contemplating and being able to integrate the words we say with true things about the world, and about God.

Part of the disintegrating nature of spin and that bull is that it is almost never substantial or integrated with deep traditions — with ideas beyond itself. Spin, or bull****, emerges from a lack of expertise, rather than expertise. The writer and academic Karen Swallow Prior has this great advice she gives her students about the pursuit of truth being about integrating deep knowledge, rather than creating totally new thinking, built off an old story by Jonathan Swift about a spider talking to a bee…

“This story within the story consists of a discourse between a spider (a “Modern,” who symbolizes for Swift the worst of modern subjective thinking) and a bee (an “Ancient,” who symbolizes the best of traditional classical learning).”

Karen Swallow Prior

The spider has spun a deadly web built from within itself, just to entrap others — and the bee, facing its death, points out that the spider brings darkness and death — it produces nothing but excrement and poison from its work; it is disconnected to anything beyond itself, while a bee builds a nourishing house of life-giving sweetness by connecting the life it builds to a community and to a structure it puts together from outside itself. She reckons our approach to finding and speaking truth — in her case it is about students being “bees, not spiders.” Integrating knowledge in their essays is about avoiding spin and building knowledge from good sources outside ourselves, but she sees her task in a post-truth world as, increasingly, helping people spot the difference between the poisonous lies of the spider, and life-giving truths — nectar.

“I see now that the challenge is increasingly to better equip students to distinguish between poison and nectar, to build from strong materials rather than to create airy edifices which, like spiderwebs, are easily swept away once their lethal work is done.”

Karen Swallow Prior

She, like Paul in Ephesians, sees the key to not being swept away, or sweeping away others, as being firmly planted in the truth of the Gospel, and having it integrated into the other truths we believe and speak.

Be bees. Not spiders. People committed to living truthfully and in love together; one with God and each other — and to speaking truthfully to each other and the world as we bear witness to the true human who is the way, the truth, and the life.