The fear of the Lord is the beginning of knowledge,

but fools despise wisdom and instruction. — Proverbs 1:7The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom,

and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding. — Proverbs 9:10

Jordan Peterson is a wise man. But just how wise he is depends on how much the these claims about wisdom are real. And if they are real; just how much one is prepared to acknowledge that not being as wise as you can be — articulating a wisdom apart from the real ‘fear’ of the Lord — is actually a form of folly. And if it’s folly, then such that if we were to doggedly follow him as a wise man, when some truer wisdom is out there is to adopt an incomplete picture of how to live. And so here, humbly (mostly pointing to the wisdom of others), I’d like to offer some suggestions to those who find the sort of wisdom Peterson offers in his videos, and his books, including his just 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote For Chaos appealing.

Peterson’s 12 Rules are strongly built on a foundation that reality occurs along a spectrum of chaos and order; the ‘ying and yang’ of Taoism; that in fact, these ‘forces’ or orientations, held in balance, are at the heart of the cosmos and the human psyche. He personifies chaos as feminine, which he argues is ‘archetypal’ but has rightly frustrated many women (especially because he has so caught the imagination of young men). The first chapter, on lobsters and dominance hierarchies, almost got its own post such is its suggestion that for men to get women to swoon over them, and date them, they need to capture some sort of ‘will to power’ and stand up straight… there was some stuff in that chapter that I felt had the tendency to leave ‘upstanding’, or ‘dominant’ men feeling entitled to be loved, and thus righteously angry at their advances being rejected.

In many ways his insights are a bit like some of the Proverbs we find in the Bible; axioms we can live by as we pursue an understanding of the ordering of the cosmos and what a ‘good life’ in that cosmos looks like. One thing the book of Proverbs teaches us is that a certain form of wisdom isn’t limited to Christians; but absolute truth about the world; a sort of ‘realer’ wisdom involves connecting truths about creation with the creator. Proverbs is structured as a series of bits of advice from a father to a son about how to be a man; it’s really a set of reflections for the nation of Israel about how to be the ‘son of God’; living well in God’s world; but scholars have long noticed that not only does Proverbs borrow large chunks from ancient wisdom (including not just content, but this form — advice to a son), it engages with a fundamental idea common in the ancient world… that the world is ultimately a balance between order and chaos. There’s an Egyptian goddess — Ma’at — and belief in Ma’at underpinned much Egyptian wisdom, including the Wisdom of Amenemope (that Proverbs quotes extensively). Here’s a bit of detail about Ma’at

“The central concept of Egyptian wisdom literature lies in its understanding of the goddess Ma’at. The daughter of the primordial creator god Amon-Re (although in later times she came to be associated with the Memphite god Ptah), Ma’at symbolizes both cosmic order and social harmony. Thus, Ma’at is not only that force which ensures the regularity of the sun god’s path across the sky each day (surely the most visible sign of an orderly universe!), but she is also order, justice, and truth in the human sphere. These two aspects of Ma’at should not be viewed as mutually exclusive, however: for the ancient Egyptian, cosmic order and moral order were inextricably bound up with one another. This may best be seen in the office of the king—the king ruled by making the concept of Ma’at the fundamental moral basis of his reign, and by doing so, reestablished order on the cosmic plane, as it was during “the first time” of creation.” — Carole Fontaine, ‘A Modern Look At Ancient Wisdom — The Instruction of Ptohhotep Revisited,’ Biblical Archeologist, 1981

More recently Michael Fox wrote ‘World Order and Ma’at: A Crooked Parallel,’ (published in the Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society in 1995), where he said:

“Ma’at, whose etymological sense is straightness, is not order as such. It is, rather, the force that creates and maintains order, namely justice/truth, a concept that we subdivide, perhaps artificially, in English… Ma’at is order: the just and true working of society maintained or restored by the efforts of God and man. On a cosmic scale, Ma’at does displace or “drive out” evil or “disorder” at creation and thereafter especially at each coronation [of a king], but it does so by divine or royal agency.”

Fox makes an interesting subsequent point when it comes to Ma’at’s intricate relationship with Egyptian mythology; that you can’t generalise principles from one mythic theology and generalise across theologies; which is pretty much Peterson’s schtick.

“The idea of Ma’at did not and could not exist in Israel. Ma’at… was the foundation myth of the Pharaonic state and was inextricable from the Egyptian religion and hierarchy. The most important and frequent statements about Ma’at, such as that Re lives on Ma’at, or that Ma’at is the daughter of Re, or rites such as the daily offering of Ma’at to Re, or images such as Ma’at in the prow of Re’s boat, can have no meaning outside an Egyptian context. Only by stripping Ma’at of its distinctive character can one even claim to find a parallel in Israel.”

I’m not sure I totally buy this, I’m more inclined to be with Lewis in Myth Became Fact (see part one of this series), that all ‘myths’ are in some sense an attempt to articulate an intrinsic ‘mythic’ quality of the human spirit. But what’s interesting is how Ma’at is both the sort of order Peterson speaks about as ‘archetypally’ male, as opposed to the feminine chaotic, that Ma’at is said to be similar to the Hebrew Hokma (wisdom, and a feminine noun), and Greek Sophia (wisdom, and a feminine noun); in Proverbs, wisdom is personified as female (symbolised as a wife to be pursued). All three ancient traditions that have some sort of archetypal ‘order’ personify that order as female. His statements about order and chaos being masculine and feminine almost universally and then his frequent dipping in to Egyptian mythology are a weird and obvious contradiction. In Egypt the personification and deification of Chaos is also a serpent — Apep, and Apep is male. He’s considered the opposite of the female Ma’at.

Ma’at, or wisdom, was the antidote to chaos — a properly ordered life — for the faithful reader of the Old Testament, who might dabble in the wisdom of the world, and find truth in a collection of axiomatic statements about reality from foreign sources, this wisdom must be built on the platform of Israel’s knowledge of the creator of that order. While Fox suggests Ma’at didn’t directly influence Hebrew wisdom — specifically the understanding that ‘ma’at’ was the fundamental order of all things — it’s impossible to deny that Egyptian wisdom influences Proverbs when Proverbs explicitly features Egyptian proverbs from the Wisdom of Amenemope. The bits where Proverbs explicitly borrows from — or quotes — foreign wisdom are bracketed with statements like those quoted from Proverbs above — the fear of Yahweh, Israel’s God, the creator of the cosmos, is the beginning of wisdom. Yahweh trumps Ma’at; both in the wisdom stakes and the mythic stakes. But in this borrowing there’s also a model for us thinking about how we might approach Peterson and his (and Jung and Nietzsche’s) mythological approach to wise living.

To understand this model one has to think about the narrative, or mythic, content the Proverbs are delivered in (in the form of the Bible, and Israel’s unfolding history); and to some extent the relationship between wisdom and gold… and Israel and Egypt. Israel, as a nation, is birthed out of Egypt; they are formed or ‘cast’ as God’s image-bearing son; his people. They are released from Egypt after God steps into history to rescue and claim them. He has Moses confront Pharaoh to say of the Israelites:

Then say to Pharaoh, ‘This is what the Lord says: Israel is my firstborn son, and I told you, “Let my son go, so he may worship me.” But you refused to let him go; so I will kill your firstborn son.’” — Exodus 4:22-23

Israel, corporately, both men and women, are God’s ‘son’. Part of the point of the exodus — where Israel crossed the Jordan — was them being declared as God’s children; to be a pattern for, or example of, wise living who were meant to bless their neighbours in part by being wise, so that the nations would see their wise lives and glorify God. In the early chapters of Deuteronomy — another guide to wise living for a ‘son of God’, Israel’s wisdom is to be part of its witness (reading Solomon’s reign, and the Proverbs, against these words is interesting, isn’t it).

Observe them carefully, for this will show your wisdom and understanding to the nations, who will hear about all these decrees and say, “Surely this great nation is a wise and understanding people.” What other nation is so great as to have their gods near them the way the Lord our God is near us whenever we pray to him? And what other nation is so great as to have such righteous decrees and laws as this body of laws I am setting before you today? — Deuteronomy 4:6-8

This is in the same chapter that Moses talks about Israel crossing the Jordan as them entering their inheritance; entering ‘sonship’ so to speak, and there’s a pretty big warning about making idols or images of God because they are his images; and his nation of priests (Exodus 19); they are meant to represent him in the world.

Therefore watch yourselves very carefully, so that you do not become corrupt and make for yourselves an idol, an image of any shape, whether formed like a man or a woman, or like any animal on earth or any bird that flies in the air, or like any creature that moves along the ground or any fish in the waters below. And when you look up to the sky and see the sun, the moon and the stars—all the heavenly array—do not be enticed into bowing down to them and worshiping things the Lord your God has apportioned to all the nations under heaven. But as for you, the Lord took you and brought you out of the iron-smelting furnace, out of Egypt, to be the people of his inheritance, as you now are.

The Lord was angry with me because of you, and he solemnly swore that I would not cross the Jordan and enter the good land the Lord your God is giving you as your inheritance. I will die in this land; I will not cross the Jordan; but you are about to cross over and take possession of that good land. Be careful not to forget the covenant of the Lord your God that he made with you; do not make for yourselves an idol in the form of anything the Lord your God has forbidden. For the Lord your God is a consuming fire, a jealous God. — Deuteronomy 4:15-24

To ‘cross the Jordan’ is to become a son of God; whether you’re male or female (there’s an interesting implication of the command not to represent God as a man or a woman, which fascinates me because of how in Genesis 1 God (plural) makes humanity in his image as ‘male and female’… and yet dynamically personifies all his people as his ‘son’; now, Jordan Peterson would see this as supporting his archetypal view of chaos and order being masculine and feminine, but I’m going to suggest Biblical archetypes work in a different way (and sometimes Peterson seems to get this, he does have a nice ‘narrative’ reading of the whole Bible going for him).

Here’s a little interlude; a short tangent if you will, about why playing genders off against each other (though with an acknowledged mutual need for one another mostly for some biological imperative) is a common worldly idea but something the Bible fundamentally undermines. I like that Jordan Peterson acknowledges some fundamental differences, biologically, physically, and in how those differences might shape different behaviour, but I don’t like how his ‘dominance hierarchy’ stuff essentially justifies a certain sort of ‘noble patriarchy’ rather than a radical co-operation-in-difference. It seems to me that his basic rendering of the biological universe and its application to human behaviour basically doesn’t just leave men as lobsters competing for status so they can claim the best mate (and be attracted to them), but also leaves us men like peacocks in a perpetual game of charming our mate — or making our desires and demands that we believe might be ‘dark’ and so hesitate to raise them, clear and open, with the expectation that our significant other will embrace them (that was perhaps the creepiest bit in the book) rather than operating in partnership with a radical sort of commitment to elevating and celebrating the other. The heart of Peterson’s model for relationships in his order/chaos paradigm is the ‘masculine’ quality of assertiveness; of making one’s will known, standing up straight, and claiming it (or at least living as though you are entitled to your will), this is pictured as a proud and dominant lobster rising as high up a ‘dominance hierarchy’ as you can. It’s a terrible model for relationships between men and women — and it runs counter to the Biblical picture of wisdom as a woman, and the advice both to Israel (as God’s son) and Israelite sons, to pursue (and presumably listen to and value) a wise partner. The problem in Genesis 3 wasn’t that Adam listened to his wife, but that she gave foolish advice (and so the ‘harlot’ or foolish woman in Proverbs is also a woman, so too the nations whose gods and women pull Israel away from Yahweh. Individualism and this sort of ‘will to power’ doesn’t work in marriage if it’s true that ‘the two become one flesh’. I’d say what gets extrapolated from how men and women relate together from Peterson’s biological account against the Biblical account is a fundamentally different ordering of society. One of the best articles I read last year was by Brendon Benz, titled ‘The Ethics of the Fall: Restoring the Divine Image through the Pursuit of Biblical Wisdom’, he makes a fantastic case for us to reconsider how we understand the dynamic of the image of God being ‘male and female’ such that a purely individualistic view of being human doesn’t work theologically. Here’s a long quote because it provides a thoroughly different ‘archetypal lens’ for reading the Bible as an organising ‘myth’ to the Jungian individualism Peterson advocates (a Jungian ‘plurality’ would be extra fun though).

Thus, wisdom demands a partner—one who is willng to speak, and at the same time, one who is willing to give ear. The result of this corporate engagement is the ability to discern between good and evil, and thereby administer justice. This identification comes as a surprise when it is juxtaposed with Genesis 1–3. In chapter 3, God judges the man and the woman unfavourably for seeking the knowledge of good and evil, suggesting that their decision to do so was not motivated by wisdom. This apparent tension is resolved, however, when it is read in light of a relational interpretation of the divine image, and according to the nature of social power advanced by such scholars as Anthony Giddens. The result is an alternative reading of the so-called fall in Genesis 3 that provides a more concrete understanding of the part humanity must play in successfully responding to the injustices that result from it. In Genesis 2:16–17, God warns the man, who is “alone” in the garden (Gen 1:18), of the negative consequences that will befall him if he violates his individual limit. This indicates that the fall narrative does not depict humanity’s transgression of a divine boundary that was intended to curb human understanding. Instead, it illustrates that the attempt to take possession of the knowledge of good and evil—an important social resource—in isolation and on one’s own terms results in the collapse of the divine image, which, according to Genesis 1:27 and Matthew 18:20, is manifest only in the encounter between the I and the Other who listen. When one understands that the events in Genesis 3 undermine the divine image as it is depicted in Genesis 1 and embodied in Genesis 2, a potent statement emerges regarding the urgency of constructing power-sharing relationships in the context of diverse communities whose members listen. As is reflected in the vulnerability of God’s own interactions with humanity in texts like Genesis 18 and John 20, such relationships are necessary if individuals are to image God, and thereby wisely administer justice…”

God’s image necessarily consists of, and therefore requires, a plurality—in this case, male (zāḵār) and female (nĕqēḇâ). This plurality of personhood is echoed at the beginning of the chapter, wherethe masculine “God” (ʾĕlōhîm; v 1) and the feminine “Spirit of God” (rûaḥ ʾĕlōhîm; v 2) are named as two of the entities involved in creation. When it comes to humanity as the image of God, therefore, Buber rightly observes that “In the beginning is the relation—as the category of being … as a model of the soul; the a priori of relation; the innate Thou” (78). In sum, Genesis 1 indicates that God is imaged only when two or more are gathered in the freely self-limiting relational character of God (cf. Murphy: 173–77). This corresponds to the words of Jesus, whom the authors of the New Testament regard as the image of God (John 1:1–3; Heb 1:1–3; Phil 2:5–8). In Matthew 18:20, he states, “where two or three are gathered in my name,” or my character (Wright 1998: 116), “I am there among them.” The implication of this requirement is that an individual neither posses the divine image as a substance of his or her own being, nor images God in isolation. Rather, the imago Dei is manifest only in relation.”

I won’t drag this out but there’s long been a connection drawn between the idea of the image of God (in the Ancient Near East) being a claim to sonship, usually by kings, so in Israel you get this broadened to include men and women (Genesis 1) and then every Israelite (Exodus 4).

When Israel crossed the Jordan on their way into the promised land they plundered Egypt; stealing its literal gold. This gold was then used to create both the golden calf (idolatrous and destructive folly) and the furnishings of the tabernacle (part of Israel’s worship of God as creator and provider of the good and abundantly fruitful life in the land). Crossing the Jordan was Israel’s path into nationhood — sonship even — and what they did with gold ultimately revealed what sort of child they were; at certain points they were wise and they flourished (and the nations flocked in to hear Solomon’s wisdom), but at other points they borrowed not just the gold of Egypt, but their gods as well. They were more likely to jump on board with the idea of Ma’at, than fear Yahweh. Which is exactly what we learn in the figure of Solomon. Solomon has an interesting relationship with Egypt, with Proverbs, and with gold. In the account of his reign in 1 Kings we get the sense that he has a fraught relationship with Egypt; that it’s a significant country in terms of his life.

“Solomon made an alliance with Pharaoh king of Egypt and married his daughter. He brought her to the City of David until he finished building his palaceand the temple of the Lord, and the wall around Jerusalem.” — 1 Kings 3:1

“And Solomon ruled over all the kingdoms from the Euphrates River to the land of the Philistines, as far as the border of Egypt. These countries brought tribute and were Solomon’s subjects all his life.” — 1 Kings 4:21

Then…

“God gave Solomon wisdom and very great insight, and a breadth of understanding as measureless as the sand on the seashore. Solomon’s wisdom was greater than the wisdom of all the people of the East, and greater than all the wisdom of Egypt. He was wiser than anyone else, including Ethan the Ezrahite—wiser than Heman, Kalkol and Darda, the sons of Mahol. And his fame spread to all the surrounding nations. He spoke three thousand proverbs and his songsnumbered a thousand and five. He spoke about plant life, from the cedar of Lebanon to the hyssop that grows out of walls. He also spoke about animals and birds, reptiles and fish. From all nations people came to listen to Solomon’s wisdom, sent by all the kings of the world, who had heard of his wisdom.” — 1 Kings 4:29-34

When Solomon prays to dedicate the temple he specifically remembers that Israel were brought out of Egypt and cast as his people like a statue from a fire, he says

“And forgive your people, who have sinned against you; forgive all the offenses they have committed against you, and cause their captors to show them mercy; for they are your people and your inheritance, whom you brought out of Egypt, out of that iron-smelting furnace.” — 1 Kings 8:50-51

In the law for the future king of Israel in Deuteronomy there’s a specific command not to take horses from Egypt; and as things turn for Solomon, the first real sign that things have gone wrong (apart from marrying the daughter of Pharaoh which was also a Deuteronomic no-no) is:

“Solomon’s horses were imported from Egypt and from Kue[j]—the royal merchants purchased them from Kue at the current price.” — 1 Kings 10:28

1 Kings wants to make real sure we know Solomon doesn’t end well; he doesn’t pursue the sort of wisdom he started out asking for; and so Proverbs becomes a sort of deeply ironic book attributed to him.

As Solomon grew old, his wives turned his heart after other gods, and his heart was not fully devoted to the Lord his God, as the heart of David his father had been… So Solomon did evil in the eyes of the Lord; he did not follow the Lord completely, as David his father had done. — 1 Kings 11:4, 6

Solomon is a pretty interesting picture of the fully realised ‘man’ or, more broadly, a representative picture of flourishing Israel… a true son of God who asks for, rather than takes hold of, wisdom from God. Here’s how Benz describes his request for wisdom:

“1 Kings 3, Solomon asks for “a listening heart (lēḇ šōmēaʿ) in order to judge your people and to discern between good and evil” (v 9). After expressing pleasure with this request, God identifies Solomon’s “listening heart” as a “wise heart” (lēḇ ḥāḵām; v 12). Read in parallel, these two statements indicate that wisdom is predicated on the capacity to listen.”

It’s interesting that the example given of Solomon’s wise listening is a court case between two women — mothers — prostitutes — one with a dead son, one with a living son; if you want to talk about archetypes there’s a strong sense that choosing the foolish prostitute who killed her son would’ve been a really bad idea for Israel’s king… and yet ultimately he symbolically (when it comes to the symbolism of Proverbs and the Old Testament picture of the nations around Israel being ‘prostitutes’ makes the unwise and morally wrong choice. He doesn’t find a wise conversation partner — a wife, a co-image bearer (or community of them) who will help him make wise decisions as he listens (David and Abigail are an interesting counter-point to this, where David does pursue a wise wife). I want to stress that this isn’t a suggestion that everybody needs marriage to be completed — but we do, in our shared life, need men and women speaking and listening in order to live the fullest vision for humanity — the ‘image bearing’ vision of faithful sonship as men and women. And this pushes back on Jordan Peterson’s archetypal framework pretty strongly…

Solomon is this positive figure for about ten minutes; and then he’s a picture of disorder and folly; and somehow the Proverbs reflect that high point before his fall. Solomon is described as being somebody in command of the natural world such that he is able to understand and document its order — and you get a sense from the narrative he was also engaging with the sages and wise men of the nations… he was also quick to have his head turned by women he should not have been pursuing, and because he was at the top of the ‘dominance hierarchy’ taking what he should not have taken; the picture in Proverbs of the wise advice from the king (Solomon) to his son to pursue a wife of noble character; the personification of wisdom, is deeply ironic against Solomon’s life and approach — but even more so against Israel’s approach to wisdom.

What’s also archetypal here, against Peterson’s system, and as mentioned above is that wisdom or order is feminine, and perhaps the brashness of masculinity needs to be tempered by a listening partnership with wisdom rather than embracing destructive folly; the gendered stuff Peterson does is inverted in the Proverbs… but the warning from Solomon’s life, and Proverbs, in history is that if you’re going to plunder gold from Egypt you better be sure not to use it to build idols, or have it pull you away from the truth about the God you should be fearing. Incidentally, later, and probably without having discovered the strong links between Proverbs and Egyptian wisdom, Augustine took the idea of plundering gold and explicitly applied it to what the Proverbs implicitly practiced — the idea that truths expressed by people in the world about the fundamental order of creation should be taken and used to their proper ‘ordering’ — their telos — which he saw as ‘to preach Christ’ (if all this stuff fascinates you, it is what I wrote my thesis on; the (short version of the) title is Plundering Gold from Egypt to Contextually Communicate the Gospel of Jesus, and it includes a big chunk on Proverbs and wisdom, and how to ‘plunder Gold’ appropriately.

The book of Proverbs, like Jordan Peterson, appears to teach men to be men, but is really a guide for all people to re-order or re-cast their lives against a background of chaos. There’s lots of ‘truth’ in what Peterson writes. But here’s the thing — the ‘mythic frame’ — the ‘story’ that wisdom is delivered in matters. Especially when that wisdom is a sort of axiomatic description of an ‘ordered life’ and where it explicitly speaks as though myth matters. It’s much harder to purely plunder Egypt, without straight up importing idols, if we’re careless about the mythic frame and the vision of masculinity (in this case) being put around those ideas, and that’s where Jordan Peterson is perhaps more dangerous than we think.

Sometimes Peterson is golden, but there are lots of places where we need to be careful that we’re not importing a wrong picture of God from his work, and carelessly popping it in our homes and lives when really it’s a Trojan calf that will pull us away from truths about God… that he seems to be on a journey himself, and taking the Bible pretty seriously as a source of truth, makes him both exciting and dangerous. Because while real wisdom begins with the fear of Yahweh; and while this was framed as an instruction manual for sonship in the book of Proverbs; we get a true picture of what it means for all Christians (men and women) to be both sons of God and brides of Christ (talk about confusing gender categories) in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus and what it means to truly follow him

There have been some worthwhile reflections on Peterson’s picture of masculinity offering Jesus as a corrective to his vision; or rather a corrected vision of Jesus (and the cosmos) as a better antidote to chaos. But I’m not sure how possible it is just to tweak his picture around the edges. Plundering Peterson might require an almost total meltdown of his rendering of Jesus and the cross and a total recasting of his vision for humanity.

It’s interesting to consider how ‘crossing the Jordan’ works as a Biblical archetype ultimately found in Jesus, and how this might invite us to cross Jordan Peterson, and understand the Cross as something more than taking responsibility and trying to save both yourself and the world… what if our real humanity is actually found in the mystery of union with Christ; that somehow our sonship is about dynamically being ‘one with him’ though still many.

Matthew takes a line from the prophet Hosea about Israel, God’s son, coming out of Egypt and applies it to Jesus own ‘crossing the Jordan’ moment as an infant — where he fled to Egypt to avoid the toxic, patriarchal, masculinity of Herod (who tried to dominate the threat posed by an infant by wiping out every infant he could find — as one worse than Pharaoh). Matthew says this ‘crossing the Jordan’ moment was so that the Old Testament archetype could be fulfilled; for ‘out of Egypt God calls his son’ — this is both a geographic call, and a spiritual one — a call to leave Egyptian dominance hierarchies and archetypes behind, and to embrace something new built on the fear of the Lord. A new picture of wisdom. Jesus has another ‘Jordan’ sonship moment when he is baptised in the Jordan. John the Baptist is baptising people in the Jordan — a picture of the exodus where Israel was created, birthed, through those waters, and Jesus arrives to be baptised. When this happens:

Jesus was baptised too. And as he was praying, heaven was opened and the Holy Spirit descended on him in bodily form like a dove. And a voice came from heaven: “You are my Son, whom I love; with you I am well pleased.” — Luke 3:21-22

Jesus is recognised as God’s son, our image of humanity, our image of image bearing, is recast in him (a theme picked up throughout the New Testament).

Jesus was ‘one greater than Solomon’ (Luke 11:31); he also drew implications for living from careful observations of the natural world (Luke 12:27 — where he invites us to consider how nature is more gloriously arrayed than Solomon, and asked how much more God might love his children); and yet his picture of the good life was not an expression of the will to power; not a case of ‘standing up straight with your shoulders back’… and when he calls us to take up our cross it is not simply an invitation to bear on our shoulders the reality of suffering; but to carry around in our lives a living breathing picture of living with a sense that death is dead. Instead of being like Solomon and taking, Jesus says those who follow in his pattern of sonship will:

But seek his kingdom, and these things will be given to you as well.

“Do not be afraid, little flock, for your Father has been pleased to give you the kingdom. Sell your possessions and give to the poor. Provide purses for yourselves that will not wear out, a treasure in heaven that will never fail, where no thief comes near and no moth destroys. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also. — Luke 12:31-34

In Jesus God becomes our father. We become his sons — whether we’re male or female, but this ‘sonship’ requires a dynamic, image bearing relationship of listening to the other and not simply being individuals with a will to power — because real wisdom is not found in dominance, but submission. Our crossing the Jordan — our exodus — our baptism — is a baptism ‘into Jesus’; a receiving of God’s Spirit to make us one with him (so individualism is tricky to maintain as a sort of exclusive picture for flourishing humanity).

So in Christ Jesus you are all children of God through faith, for all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ. There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus. If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise. — Galatians 3:26-29

Jordan Peterson is a wise man offering a reasonable version of Egyptian wisdom (except he should invert the genders of order and chaos). He offers a reasonable ‘Egyptian’ attempt to plunder the gold of true Israel. But until he understands the world inverting foolishness of the cross, until he fears God, I’m not sure it’s wisdom at all, and I’m pretty skeptical of claims about his usefulness for the church without some serious re-framing and melting down of whatever gold it is he offers so that it can be used in service of the creator.

Real wisdom is not found in power but the fear of the Lord and the subversive wisdom of the Cross. You want to see how the crucified Jesus is archetypal? Look at Paul. His teachings and his life. I’ll flesh this out (in an almost literal sense) in the next post, but here’s what he says about the wisdom of the world and how it is confounded by the cross not just subtly tweaked… this is what really ‘fearing God’ looks like — seeing human strength and dominance as foolishness in the face of God’s power and his operations in the world.

Where is the wise person? Where is the teacher of the law? Where is the philosopher of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since in the wisdom of God the world through its wisdom did not know him, God was pleased through the foolishness of what was preached to save those who believe. Jews demand signs and Greeks look for wisdom, but we preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those whom God has called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. For the foolishness of God is wiser than human wisdom, and the weakness of God is stronger than human strength.

Brothers and sisters, think of what you were when you were called. Not many of you were wise by human standards; not many were influential; not many were of noble birth. But God chose the foolish things of the world to shame the wise; God chose the weak things of the world to shame the strong. God chose the lowly things of this world and the despised things—and the things that are not—to nullify the things that are, so that no one may boast before him. It is because of him that you are in Christ Jesus, who has become for us wisdom from God—that is, our righteousness, holiness and redemption. Therefore, as it is written: “Let the one who boasts boast in the Lord.” — 1 Corinthians 1:20-31

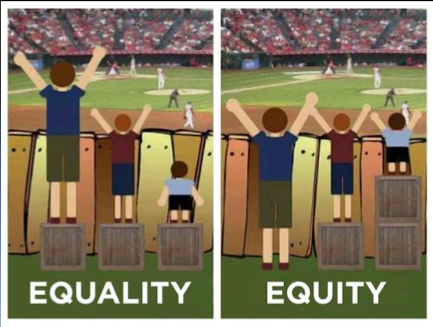

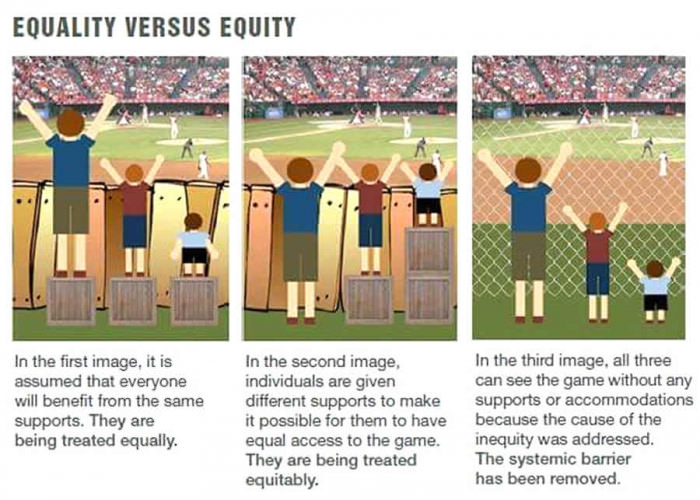

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As