My denomination has been in the news over the last week, because a financial situation that has been bubbling away for some time has reached a head. Please, if you’re a Christian whose been reading these stories and trying to understand how we could all get it so wrong — suspend judgment for a moment, and take time to pray for those involved in the legal and financial situation at the coal face, and for congregations around Queensland wondering what this means for their church communities. There’s more to this story than simply bad governance, or a church’s historic involvement in a complex industry, and I’ve seen more than one public conversation where people have the wrong end of the stick; or perhaps have only grabbed hold of part of the elephant…

The situation also requires more than people with a ‘thin’ Gospel (one that emphasises proclamation alone, without meat on the bones, or boots on the ground) saying that churches shouldn’t be involved in these industries in the first place. I was reminded, over the weekend, that the way the early church gained a foothold in the community in the first few centuries was running something like a burial society — burying those people who could not afford a fancy funeral. We’ve always been called to love and serve people in complex areas at the margins of our society — and we in the west dehumanise and devalue our old people (or at least remove them from sight/having value) before they die, by shuffling them off to these halfway homes to be cared for by a marginalised workforce (who, were, for example, disproportionately affected by Covid in Australia because of where they live, in high density housing at the margins of the community where social distancing is tricky, and the nature of their work). It wasn’t wrong, necessarily, for the church to be involved in this ministry — whether it has been conducted as a ministry of the church is an entirely different question, and one we should answer.

This crunch moment has been coming for some time — in one form or another — and so the Presbyterian Church of Queensland has been conducting a review of the denomination and its ministries across the state. A Review Committee was appointed, and they asked for submissions from ministers, elders, and members in our churches across the state. The review now becomes either pointier, or pointless, depending on how receivership unfolds. But, for what it’s worth, here is my own contribution to that discussion. It is not short, but the short summary of what I’m suggesting needs to be reconsidered in our denomination is:

- The Role of women — especially their absence in rooms where key decisions are made. We can have male eldership, and listen to (and seek) the wise counsel of our fellow image bearers in the co-operative task of representing God in his world, cultivating the community of the Kingdom of Jesus, and stewarding the world he put us in to rule over.

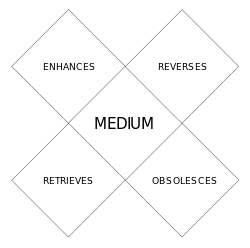

- An obsession with ‘technique’ and ‘technology’ rather than spiritual health — part of this is that we’re too wedded to modernity, and the idea that people are brains on sticks who will follow a path towards personal growth (and thus church growth) if we just get our systems right.

- A defining narrative that keeps looking back to the glory days of ‘avoiding liberalism via church union’ which means we don’t ask good questions, or imagine change and innovation that will help us engage the current cultural landscape with the good news of Jesus.

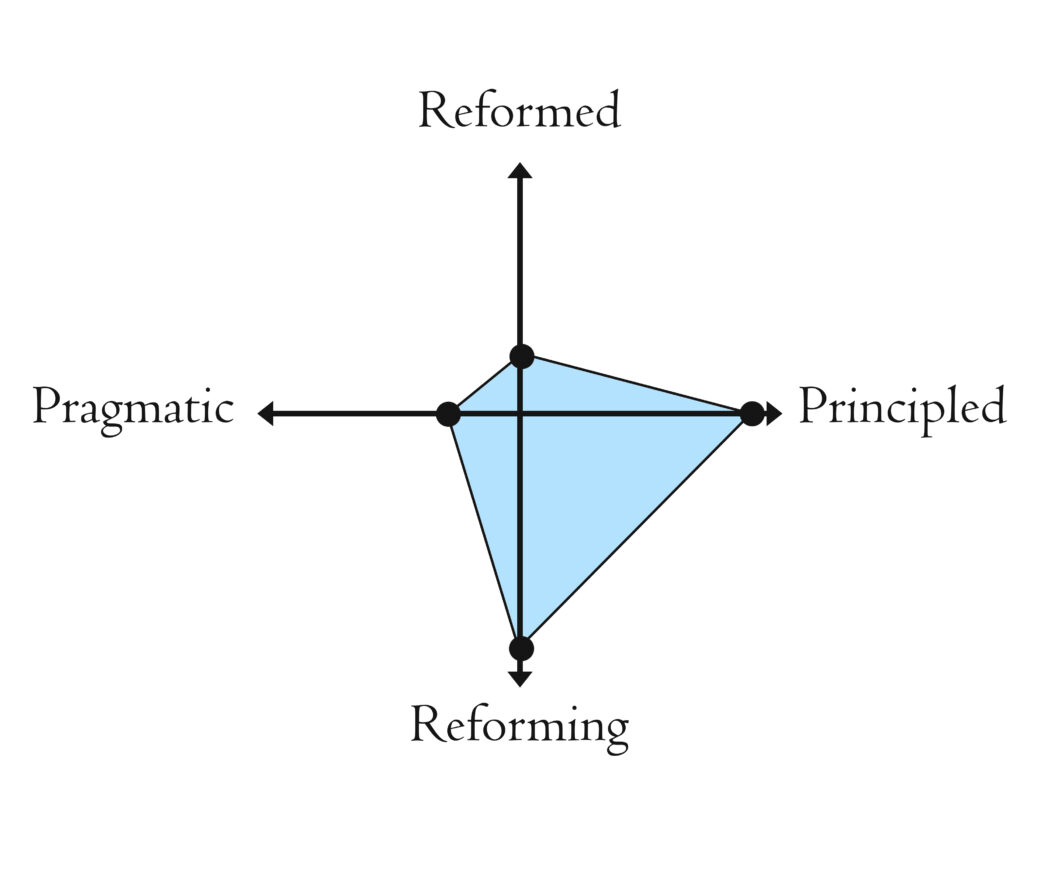

This means, for example, that we ourselves are suspicious of the sort of ministry that aged care could have been for us, and allowed a company to operate without any genuine interest from ministers and elders in the denomination. We have become ‘Reformed’ and stagnant — increasingly looking to pre-Union theological commitments (especially those of the Westminster Divines), and perhaps the ‘doctrine/historical theology’ department of our college as authoritative, rather than ‘Reforming’ — continuously looking to the Bible (and the Biblical studies department of our college) to grow to be the communities God has re-created us by his Spirit to be. The WCF is a beautiful expression of our theological convictions, but it is the ‘subordinate’ not ‘supreme’ standard for a reason. Ideally the Doctrine Department and Biblical Studies departments are working in concert and steering the ship; but we’ve tended in one direction culturally and lost some imagination in the process.

- Seeing our Presbyterian polity and structures as a ‘bug’ not a feature — we keep trying to work around systems that are an impediment to a certain sort of growth, rather than seeing those systems as a deliberate and thoughtful limit that prevents the kind of growth that might cause problems. Whether that’s in the structure of local church communities, or at a denominational level — sometimes the fence is there for a reason. Part of the solution in this present crisis is to be more Presbyterian in our governance (and culture).

We were asked to respond to five questions; which appear as headings below.

1. What have the current PCQ challenges revealed about the changes we as a denomination need to consider and why? For example, what do we as Congregations, Sessions, Presbyteries and a Denomination need to let go of? What new approaches to how we work together do we need to find? Have we discovered any new strengths?

I believe the current crisis — the PCQ Apocalypse — has pulled the curtains back and revealed a scene less like the apocalyptic vision of the majesty of Jesus in Revelation 1, and more like the old man peddling a machine behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz. This is a useful comparison because in John’s apocalypse Jesus is revealed as the transcendent Lord of all; the victorious and risen king of heaven and earth; while the Wizard is revealed to be merely human, pulling off faux-mystery in an immanent world by pulling the right levers and pursuing an agenda on human power alone.

I believe one fundamental piece of revelation in this ‘PCQ challenge’ is that we have, as a denomination, become wedded to technology and technique; to pragmatism and market based thinking and solutions; we have immanentized our concerns, and our denominational operations at exactly the time we should have been pulling back the curtain that is the barrier between heaven and earth, and unpacking what it means for us to live as God’s living, breathing, temple — filled with the Holy Spirit — in an age that is obsessed with technology and technique because our culture has closed itself off to the transcendent. This situation has revealed that we, as a denomination, have been placing our trust, and our energy, in the wrong places.

Here’s an anecdotal example; I have been attending PCQ Assemblies for seven years now as a member of the courts of the church. If we were to add up time spent in discussions on the floor of the Assembly and to weigh training seminars on technique/technology, discussions about the business of running an aged care corporation with a variety of subsidiaries, reports from schools and hospitals where the secular/sacred divide is heavily enforced, and time spent thinking theologically about our mission, or presence, in the world; the overwhelming majority of our time and headspace has been devoted to the former, not the latter. When we do think theologically – typically as GIST reports — we think almost exclusively about sexuality and gender, and not about greed, pragmatism, Christian ethics (beyond sexual or medical ethics), or theological anthropology. We are ill equipped, in our practice, to handle a crisis because we have normalised not thinking theologically, but thinking pragmatically.

Our courts function largely as bureaucracies making decisions about efficiency, and increasingly judging our performance on ‘results’ where the metrics are brought over from the realm of business.

We devote our theological energy to fighting against idolatrous cultural forces that are not our biggest threat; spending much more energy in the area of sexuality on how we deal with LGBTIQA+ social pressures, and almost no time on pastoring people with porn addictions, or addressing our own systemic greed, racism, or the besetting sins of the modern western church.

We might flinch at the idea of ‘racism,’ but I am yet to see any discussion of ministry with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples discussed, or the pursuit of meaningful representation or acknowledgment of past injustice perpetuated by the church around land, and the stolen generation (while that is a significant conversation outside the church).

We are blind to our blind spots; and have closed off avenues for self-reflection, and thus for genuine repentance and change because we have stopped ‘always reforming’ and started assuming that our default ecclesiology, theological anthropology, and ethical practice is correct; this ‘present situation’ has revealed the limits, I believe, of operating the church like it is a business (at an institutional level, but perhaps also at the level of the local congregation).

The philosopher Jacques Ellul wrote The Technological Society in 1954. He described a cultural shift that had become obsessed with technique in the pursuit of efficiency; all other concerns became secondary. He said “technique is the totality of methods rationally arrived at and having absolute efficiency in every field of human activity.” This obsession with technique in the ‘technological society’ we find ourselves living in in the modern, post-industrial (and now digital) world, coupled with a default mode of operating that ignores the transcendent, or at best, sees God at work in the mechanics of ‘efficient’ day to day life gives birth to an ethical system that is not just pragmatic (what works efficiently), but utilitarian (what works efficiently and produces the best results).

Alisdair MacIntyre describes a similar social shift in After Virtue, where the pursuit of utility creates bureaucracies obsessed with technique and ‘right order;’ and the development of the ‘management’ class. MacIntyre’s critique is, especially, that we have lost more ancient (and Biblical) concepts of virtue and character, as we have lost a sense of our ethics (and actions) being shaped according to a “telos” (purpose, or ‘end’ in the way ‘end’ is used in the Westminster catechism). He said things like: “Whenever those immersed in the bureaucratic culture of the age try to think their way through to the moral foundations of what they are and what they do, they will discover suppressed Nietzschean premises.”

Our church operates as part of the ‘technological society’ in a post-virtue bureaucracy, where, as we drill down into our practices and metrics, such Nietzchean premises (although ‘baptised’ in missional language) are operating.

The Church Growth Movement is one example of the fusion of the ‘Technological Society’ and the post-virtue pragmatic/utilitarian bureaucratic approach to church. When missionary Donald Macgavran returned to the U.S from India and realised the western world had become ‘post-Christian’ and a ‘mission field’ — he turned to the world of business and marketing/advertising for solutions to grow the church; Christianity became a product, and the church became a corporation. Pastors and elders became managers and bureaucrats, while the flock became consumers not members of the body. The metrics became numerical and financial growth, not maturity and formation of disciples.

Our churches — and even our involvement with Prescare — are expressions of the same sort of bureaucratic pursuit of efficiency through technique; ministry leaders hunt for silver bullets to grow our churches according to metrics that are not connected to our telos, but to ‘mission, vision, and values’ statements that could be photocopied from a fast food outlet (or shopping centre).

This phenomenon isn’t only visible at the denominational level, in the failure of the Assembly to properly mitigate against the risk of this present catastrophe; the same approach is effecting the ministries of local churches: as ministers burn themselves out trying to break through ‘church growth barriers’ (like the ones described in Keller’s Church Growth document), especially by becoming bureaucrats and managers of human resources, as team ministries collapse because very few of us are gifted or equipped to manage staff teams, and as we feed a culture of consumerism by shaping the experience of church around the technology or techniques we employ (think, for example, about how local churches ‘pivoted’ in the pandemic).

Our prevailing question cannot simply be ‘what works best to achieve good results’? but ‘what is the right and Godly thing for us to do for God’s glory’? That we ask the former, and not the latter, question is evident, also, in the handling of information during the Prescare crisis; justified not by our ecclesiology, or theology, or a commitment to transparency and truth at cost to ourselves, but by ‘commercial in confidence’ reasons at the advice of professionals from outside the church. We got into this crisis because we acted in ways inconsistent with our ecclesiology (why were we running a complex network of corporations in the beginning, that we did not have the expertise to manage), and when we say this is a ministry of ‘the church’ what do we mean by the church? And we have not responded to this crisis in a manner consistent with our ecclesiology.

When it comes to ethical questions we should be working from the ‘ends’ or telos, and from the character life towards those ends requires in us, or, as MacIntyre puts it, “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’”

These forms that come from a technical, post-virtue society — the practices and culture we bring in from the world of business and bureaucracy — form us, and leave us, as people and an institution, ill equipped not just to handle an erupting crisis, but to make good and right decisions in the build-up. Unless we address this culture, a changing of the guard in the denomination will not represent us learning or reflecting, but us looking for a different technique, or silver bullet.

Unless we shift our theological ethics from pragmatism or utility (often in the name of ‘mission’) to emphasise developing the character or virtues produced in disciples of Jesus, as we pursue our chief end (“to glorify God and enjoy him forever”), we are doomed to repeat these same mistakes over and over again. This isn’t to say there is no place for wisely adopting ‘truths’ from the world outside the church; nature is God’s second book; but we must ask if when we plunder the gold from Egypt we are bringing in idol statues, or melting it down to furnish the Temple for God’s glory.

If you were to set four or five strategic priorities for us as a denomination for the next five years, what would they be?

- Re-imagine our practices from first principles.

Invest time and effort into developing a culture that is not shaped by ‘worldly metrics’ but by a theological vision — an ethic born from our theology (including Christology and pneumatology), anthropology, ecclesiology, and eschatology.

We must keep, as children of the Reformation, pushing back to ‘first principles’ in our decision making. We pump out church leaders, and elders, who are great at pragmatic system building, and utilitarian calculations, but often do not give time to theological reflection, or prayer, or thinking about how our action (or simply our being) serves to bring God’s presence to the world as his image bearing people and the body of Christ.

- Re-form our understanding and articulation of the Gospel, and so our communities as plausibility structures for the Gospel that form us and witness to God’s kingdom, and his king, Jesus.

This requires deepening our ‘gospel fluency,’ in order to sharpen our Gospel proclamation (in word and deed) by asking questions about where worldly thinking has crept in not only to our structures, but our articulation of the Gospel (for eg, to what extent have we assumed liberalism and capitalism are ‘goods’ that represent truth not upended by the crucified King being what God’s wisdom actually looks like). If the Gospel is not simply ‘God saves individual sinners through repentance’ but “Jesus is the Lord and King who brings forgiveness of sins, and the kingdom of heaven, by pouring out his Spirit to make us new,” then as we live as communities of renewed people who love the Lord our God with all our heart, soul, and might — as people filled with the Spirit — and so love one another, and love our neighbours, because we now know what love is — this becomes the plausibility structure for the Gospel both for our people as we become disciples, and for our neighbours as we invite them to meet Jesus. This is what it looks like to ‘know what story’ we are living in, and this story must shape our ethics.

If we can’t articulate how a practice is an expression of that story, we shouldn’t be doing it.

This would lead to a fuller and deeper sense of how the Gospel is good news about an alternative kingdom, expressed in alternative communities, to the world that is subject to the powers and authorities in league with the ‘prince of the air’ and allow us to properly question the forms of ‘worldly’ wisdom, truth, or practices we embrace in this new stage of denominational life, and would sharpen our articulation of the Gospel and our critique of the idolatrous patterns of this world.

- Re-enchant our gatherings, spaces, and sense of purpose.

Our church practices are often thoroughly secular, and instead of forming disciples of Jesus who have their eyes fixed on ‘things above’ where we are raised and seated with Christ, through our union with him by the Spirit, we are occupied with ‘earthly things’ — our church practices, because we borrow so much in terms of ‘forms’ or ‘mediums’ from the world around us don’t ‘renew our minds’ but ‘transform us into the patterns of the world.’

We are already new creations in Christ, and our use of time and space — our engagement with God’s world — should (including and beyond the Sunday gathering) involve a robust and embodied commitment to life in God’s kingdom as an expression of the ‘now and not yet’ reality that the kingdom of heaven begins here and now in those of us who are already seated in the heavenly realm.

This might look like being a church that commits to developing a doctrine of work that sees it as more than just a place to earn money to give to church, and a doctrine of creation that sees us valuing beauty, the arts, and architecture. The artist Mako Fujimura talks about this task as ‘cultivation’ or ‘creation care’ and specifically calls for Christians to be ‘generative’ — people who live and love in ways that are life giving and productive alternatives to the systems of consumption and death outside God’s kingdom.

- Re-image our church to fully reflect the divine image — male and female — living as co-labourers/collaborators in the kingdom.

Our theological anthropology is built on the claim that male and female are made in the image of God, and that the ‘telos’ of the image of God is ultimately revealed in the “exact representation of his being” and the “image of the invisible God,” Jesus. That we are “all one in Christ Jesus” — this should not eradicate the differences between men and women, and yet, the story of the Bible, both in creation, Israel, and the church seems to envisage men and women as co-laborers and co-heirs in the kingdom who are united to Christ by the same Spirit, and united as one in his body, the church.

That this difference is expressed in different roles in the church is one of our denominational distinctives; and yet, there is nothing in the Bible that pictures, at least so far as I can tell, courts of the church that are essentially closed off to the wisdom and counsel of women; or to their participation in discussions about the business of the church; that the courts of the church are closed to women seems particularly egregious, theologically, when our Presbytery and Assembly meetings are not given to the Spiritual oversight or ‘teaching’ ministry of the church (ala 1 Timothy 2), but to pragmatic business decisions that would no doubt be best served if the wisdom of the whole was more readily available to us.

There is no Biblical reason not to restructure our courts to include the voices of women, appointed by church communities to this role; to do so would not necessarily undermine the role or office of elder (or require expanding it), but would allow our elders and ministers to consider the counsel of women on pastoral and wisdom related issues arising in the life of the church. It is no coincidence that wisdom is consistently depicted as a woman in the Old Testament, and that the wise life consists of listening to wise counsel.

That Paul sees a place for women praying and prophesying (1 Corinthians 11) in the public life of the church, and consistently describes women as his fellow workers and partners in the Gospel suggests to me that we could rethink our structures and gatherings locally: from pastors and their wife, or female ministry workers and their husbands, and how we view the calling of vocational ministry for a household within the household of God, through to wives of elders (who Paul seems to believe must be qualified on the basis of godliness, ala 1 Timothy 3), through to stewarding the gifts and wisdom of married and single women in our churches in ways that draw on these gifts for the management of the household, or economy (οἰκονομία) of the church, the household of God.

One theologian, Brendan Benz, suggests that because we are image bearers of the Triune God, the image of God is actually most fully on display in relationships, not in our individual lives, specifically in relationships built on love, and listening, in the pursuit of wisdom and godli(ke)ness.

Reformed theologian and writer Aimee Byrd has much wisdom to offer on this issue in her recent work Recovering (from) Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

3. To achieve these priorities, what changes do you think we need to make in the way the denomination is structured, the way we relate, how we are governed and how individuals and committees are held accountable within our denomination? What resources do we have or need, to achieve these priorities?

I believe our obsession with pragmatism — or technique and efficiency — means that we have spent years trying to circumvent the slow and clumsy nature of Presbyterian Government, but it is that very form of government (that ordained ministers and elders swear to own, and defend) that should’ve been a bulwark against our adoption of worldliness.

Our best resource is our Presbyterian form of Government and the natural limits it imposes on change, church size (including ministry team size), and speed of decision making processes. Anything that is too complex for us to manage under our current system should be a warning light on the dashboard that we shouldn’t be doing it.

We should abolish Commission of Assembly — or significantly minimise its scope to declare business ‘urgent and emergent’ — especially where the technology now exists for meetings to be held, and called, using digital technology. Not because this is a pragmatic ‘technique,’ or technical solution, but because we would be applying the PCQ Code to the appointment of committees, and so see administrative responsibility as a delegated responsibility under the Spiritual responsibility of the courts of the church; such that committees and commissions operate with greater accountability to both the Assembly, and our local church sessions and congregations. How can we reflect on spiritual or theological failures in our decision making processes when those processes are opaque to those who hold that responsibility?

We should abolish many of our committees that are not particularly necessary to manage the areas of ministry and mission identified in our code. And we should stop seeing the solution to our present crisis as being more Anglican (whether in the power and authority we give individuals, or committees), or being more centralised, or being more ‘top down’ led by particularly gifted leaders or visionaries. In the words of Bonhoeffer, God hates visionary dreamers.

Our best resources for equipping us to do the work outlined above are our local churches, and our theological college. Our college and faculty should be encouraged to form the sorts of thinkers — men and women — who might lead us in the sort of necessary theological thinking and towards wisdom, not pragmatic ‘leaders’ who produce visionary techniques to break through barriers when we don’t understand why those barriers are there to begin with (ala Chesterton).

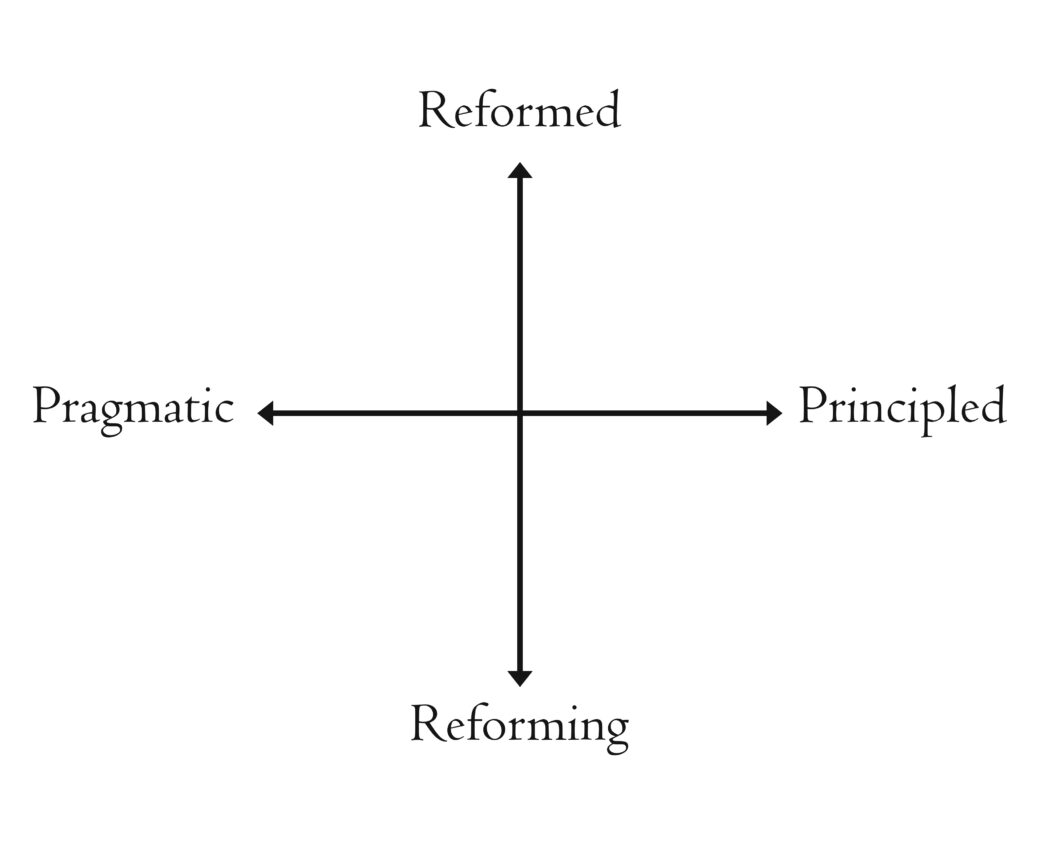

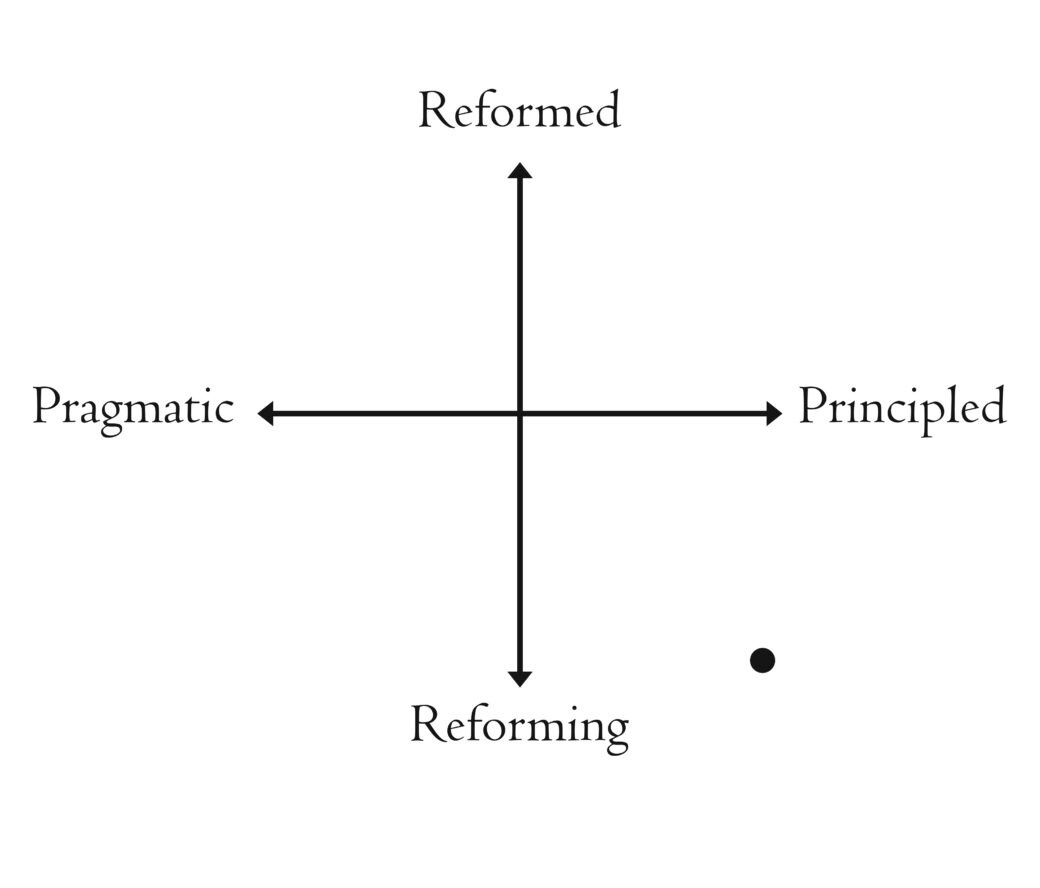

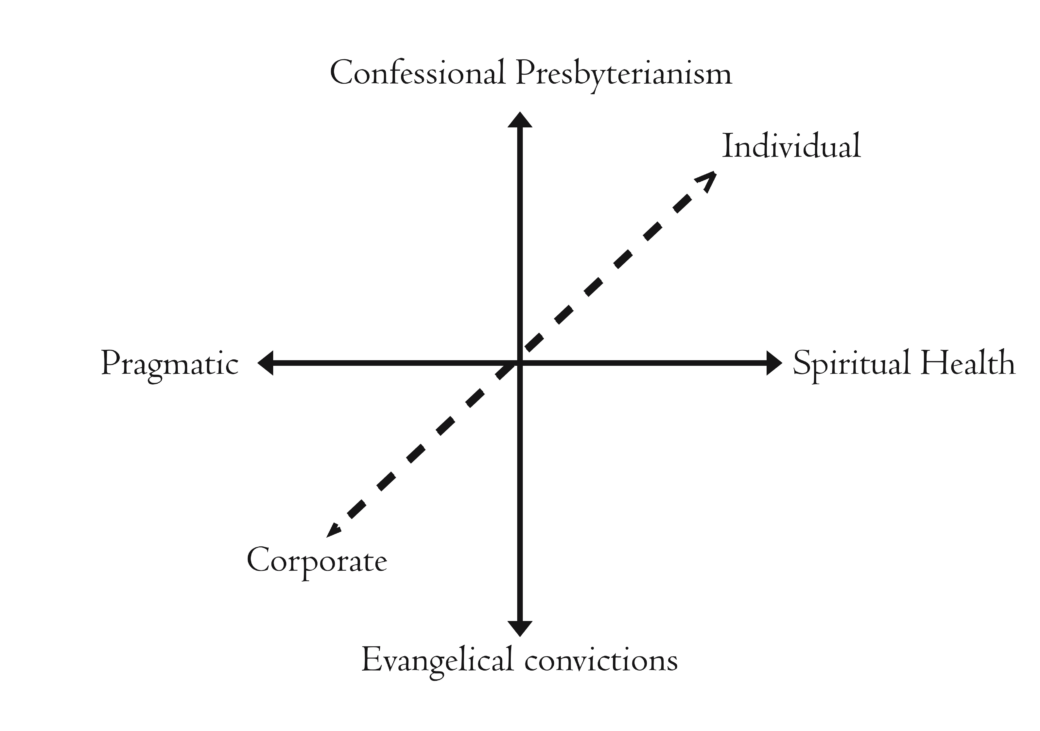

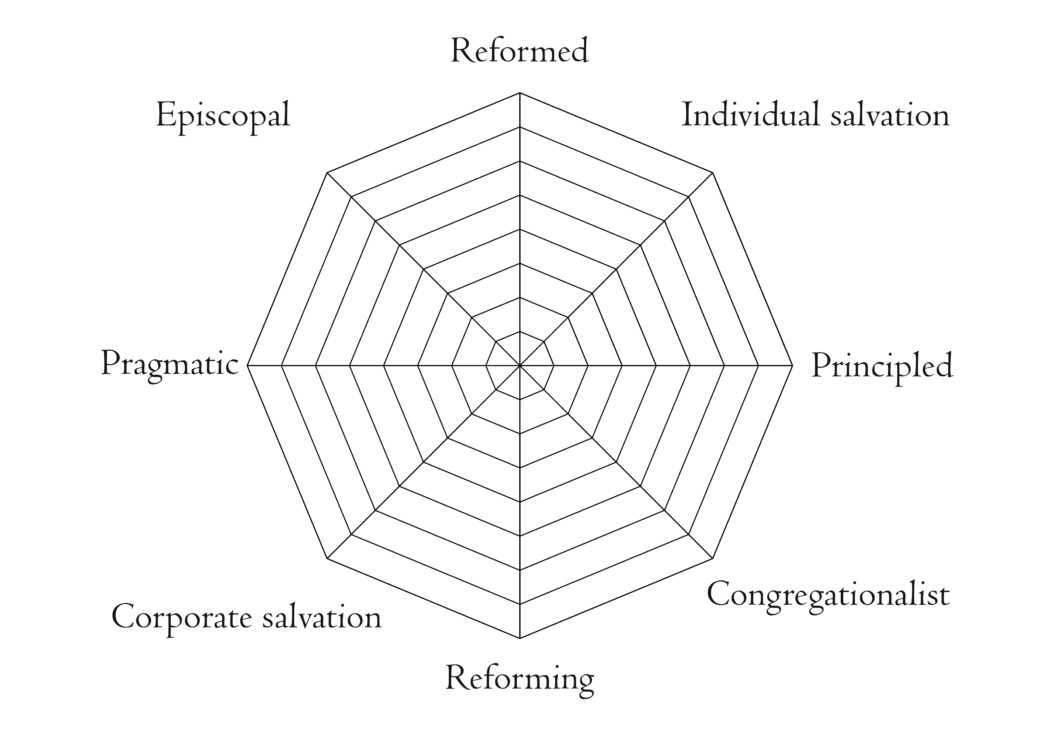

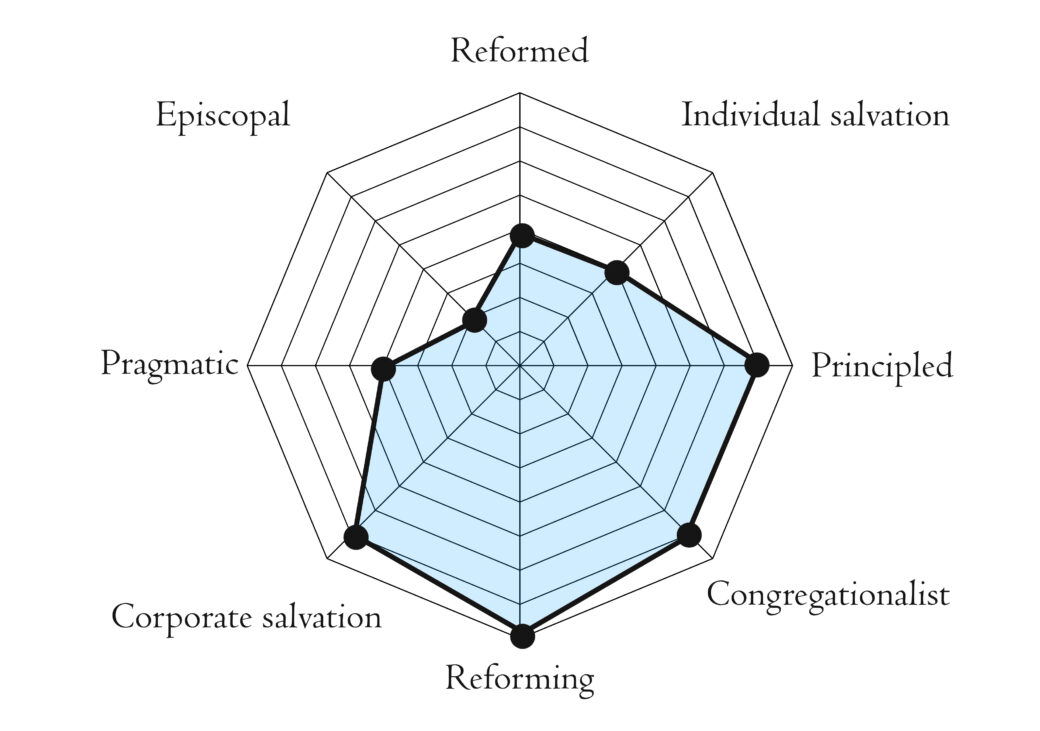

Part of pressing harder into our Presbyterian distinctives means defining whether we view ourselves as Reformed and Confessional, or Reforming and operating with the Confession and the Declaratory Statement and Basis of Union. The pressures being placed on Christians by the world outside the church, but also by ‘progressive’ agendas within the wider church, are producing an impulse to define ourselves in more black and white terms where once we were comfortable with liberty of opinion and appealing to the supreme authority of the Scriptures. Fear of ‘progressive’ agendas — especially with Church Union as part of our defining narrative as an institution — limits our capacity for truly ‘catholic’ or evangelical progress or Reform, and enshrines tradition (and the Confession) as perhaps more authoritative than it ought be (especially in the light of the Declaratory Statement and Basis of Union).

To be ‘reforming’ rather than ‘Reformed’ would require us to allow a greater plurality of theology and practice within the framework provided by the Basis of Union and Declaratory Statement; and would mitigate against any impulse to respond to present circumstances by pushing for more centralisation or uniformity in practice (or theological vision).

Our cultural push towards an “episcopalian” system of government (and culture), where committees and denominational office bearers function as Bishops, has led us to a sort of ‘church politicking’ where those committees exercise disproportionate influence (authority even) as they ‘speak for’ the denominational institution. Our denomination, both in Queensland and Federally is a ‘broad church’ that shares particular distinctives, but an expressed commitment to Christian liberty. And yet, our cultural milieu, and particularly the way politics is played outside the church in the ‘culture war’ struggle for power and ideological dominance — perhaps especially as our secular culture has lost a shared transcendent foundation — means we have turned church politics, and committee membership into a sort of ‘civil war’; as MacIntyre puts it “modern politics is civil war carried on by other means” — if we do not define ourselves as deliberately broad, with a shared theological centre, but as rigidly confessional, then such a move is a form of ‘civil war’ against those in our numbers (and congregations) brought into our fellowship, or communion, through evangelical commitments or the animating spirit of the Reformation, rather than particularly Presbyterian or Reformed (Westminster) commitments.

A commitment to ‘reforming’ rather than ‘Reformed’ principles would mean pushing for our thought leadership at the College and Committee level to value diverse perspectives within a broad framework, whereas a push to Reformed principles would necessarily narrow the participation and scope of both the College and our Committees. We should articulate our approach here with clarity such that ministers, sessions, and congregations are afforded the opportunity to stay or depart in the same way that any amendment to the Basis of Union triggers such an opportunity; because to push towards ‘black and white’ and centralisation, away from the Declaratory Statement and the emphasis on liberty of opinion in the Basis of Union is to introduce significant change; and we should have the integrity, as a denomination, to acknowledge that.

4. What do you think a healthy Presbyterian denomination looks like in 21st century Australia? For example, what services and processes, formal and informal would a healthy denomination provide to churches, ministry workers and presbyteries?

Unpacking some of the above, I believe a healthy denomination looks like:

1. We practice what we preach: A church of people with theological and ethical integrity, whose lives and doctrine are a coherent witness to the nature and character of God as revealed in the person of Jesus.

2. A broad community committed to listening, discerning, and truth telling, seeking to ‘truth in love’ in the pursuit of transformation into the image of Jesus as our model of maturity.

3. A community whose methods and metrics aren’t uncritically adopted from the ‘patterns of the world’ but that are the products of engaging in God’s world as a community of people who have the mind of Christ, the wisdom of God, and who are being transformed by the Spirit. Health looks like Godliness, and communities producing and embodying the fruit of the Spirit in their interactions with one another and the world, and people shaped to do the work of the kingdom not only in Sunday gatherings, but in God’s world as we work for his glory.

4. A community committed to union with Christ, who see diversity in the body of Christ as an expression of the breadth of God’s love and the radical inclusivity of his kingdom. This would be a church community that celebrates the ‘less visible parts of the body,’ that values the contributions of women and men, that creates an environment where people can participate in the life of the church regardless of education, or class, or ethnicity. It would be a church community that values singleness as a vocation, not just marriage (and so doesn’t talk about unmarried women in the courts of the church as though they are incomplete without a husband). It would be a church community that includes those committed to celibacy, living ‘as eunuchs for the kingdom’ as they subordinate their sexual desires to their love of Jesus. It would be a community that sees inclusivity as involving listening, and pursuing the wisdom of, all of its members in making decisions, wherever possible.

5. A community led towards godliness by leaders — men and women — committed to personal godliness, and to appropriate vulnerability, confession, and accountability for error, and to transparency in decision making. This would look like conducting far less business of the church in closed court, and being far more consultative in our practices. But it would also look like developing a culture where people own their failures, and repent, and find forgiveness; but also where accountability and healthy conflict is possible and encouraged – not a culture of rubber stamping the ideas of prominent and popular leaders.

6. A community that operates with trust, rather than loyalty — where that trust is democratised, and built, again, on transparency and seeking wisdom ‘outside the room’. Where we subject decision making to scrutiny from within the church, and from organisations outside the church as a norm. The most damaging aspect of the present crisis is how often whistles were blown, and ignored, through a loyalty culture.

7. A decentralised communion with a strong commitment to a theological centre — but freedom (and diversity) in the areas of methodology. There has been a culture of centralising a variety of services in a bid to centralise our mission, vision, and values as an organisation. I do not believe this is healthy.

8. A commitment to church planting and revitalisation in urban, regional, and rural areas with a sustainable model of church community and leadership so that our people, and our physical spaces can be better stewarded for the kingdom.

Our denomination has celebrated large churches with team ministries, and spent time seeking to accommodate these ministries into our polity because they hit the metrics we have valued. These ministries are not always going to be the best ‘technique’ for producing the metrics that matter; the training and equipping of the saints for works of service, or the sorts of communities where every member of the body is honoured and contributing, or the environments where elders (and teaching elders) can properly discharge the tasks of eldership (as outlined in the New Testament); such churches require a shift to bureaucracy, and often break through natural ‘barriers’ by restructuring community life such that members of the body no longer know, or are in fellowship, with one another. This turns a feature of church life into a bug to be squashed. This model raises the bar for vocational ministry in our denomination to heights nobody but ‘particularly gifted’ leaders can scale; but also creates conditions where the broader church rewards and normalises narcissism rather than godliness (see De Groat’s When Narcissism Comes to Church), and emphasises technique, technology, and the consumption of a product over character and participation.

Equipping us, as a denomination, for this vision of health would require (from least to most important):

1. A well-resourced theological college that looks beyond simply training clergy, and considers how it might equip elders and members of our churches to think theologically and contribute to the shared work of the church, but also a college that values diversity of opinion on areas of liberty and encourages broad, interdisciplinary, thinking and the integration of theology and practice.

2. A group of Godly, trusted, and experienced men and women offering their time as mentors and coaches; not to implement a centralised mission in pursuit of particular metrics through the appropriate technique, but who are committed to post-college training and developing of theological and cultural reflection, as well as self-reflection and growth towards godliness

3. Presbyteries to build a culture of trust, and a network of relationships that allow Presbytery meetings to function as places of theological reflection on practices and decisions, and to not simply operate as pragmatic decision making bodies around a nebulous ‘vision’ for their area.

4. Sessions that are equipped to see their task as primarily theological and pastoral rather than practical; elders who are appointed because their households are models of the households we hope to see influencing the household of God.

5. Elders who are prepared to say no to the worst impulses of pastors, not to operate as ‘yes men’ in service of visionary goals that will take a church community (including its leaderships) beyond the size it can manage well.

6. Ministers committed to godliness and the development of a life of character that aligns with the story of the Gospel (and displays the fruit of the Spirit), and comes from a prayerfully dependent relationship with God; the story they then model teaching and proclaiming; above all else.

7. Members of our church families who are shaped as resilient disciples through life in communion with God and with his people, through the teaching of his word, prayer, and formation as worshippers of the Living God who is revealed to us most clearly in Jesus, and who are equipped, encouraged, and unleashed to serve him in his world.

5. What kind of culture would we have if we were a healthy denomination? How might that culture come about and be sustained?

They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to fellowship, to the breaking of bread and to prayer. Everyone was filled with awe at the many wonders and signs performed by the apostles. All the believers were together and had everything in common. They sold property and possessions to give to anyone who had need. Every day they continued to meet together in the temple courts. They broke bread in their homes and ate together with glad and sincere hearts,praising God and enjoying the favor of all the people. And the Lord added to their number daily those who were being saved. — Acts 2:42-47

For just as each of us has one body with many members, and these members do not all have the same function, so in Christ we, though many, form one body, and each member belongs to all the others. We have different gifts, according to the grace given to each of us. If your gift is prophesying, then prophesy in accordance with your faith; if it is serving, then serve; if it is teaching, then teach; if it is to encourage, then give encouragement; if it is giving, then give generously; if it is to lead, do it diligently; if it is to show mercy, do it cheerfully.

Love must be sincere. Hate what is evil; cling to what is good. Be devoted to one another in love. Honor one another above yourselves. Never be lacking in zeal, but keep your spiritual fervor, serving the Lord. Be joyful in hope, patient in affliction, faithful in prayer. Share with the Lord’s people who are in need. Practice hospitality.

Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse. Rejoice with those who rejoice; mourn with those who mourn. Live in harmony with one another. Do not be proud, but be willing to associate with people of low position. Do not be conceited.

Do not repay anyone evil for evil. Be careful to do what is right in the eyes of everyone. If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with everyone. Do not take revenge, my dear friends, but leave room for God’s wrath, for it is written: “It is mine to avenge; I will repay,” says the Lord. On the contrary:

“If your enemy is hungry, feed him;

if he is thirsty, give him something to drink.

In doing this, you will heap burning coals on his head.”

Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good. — Romans 12:4-21