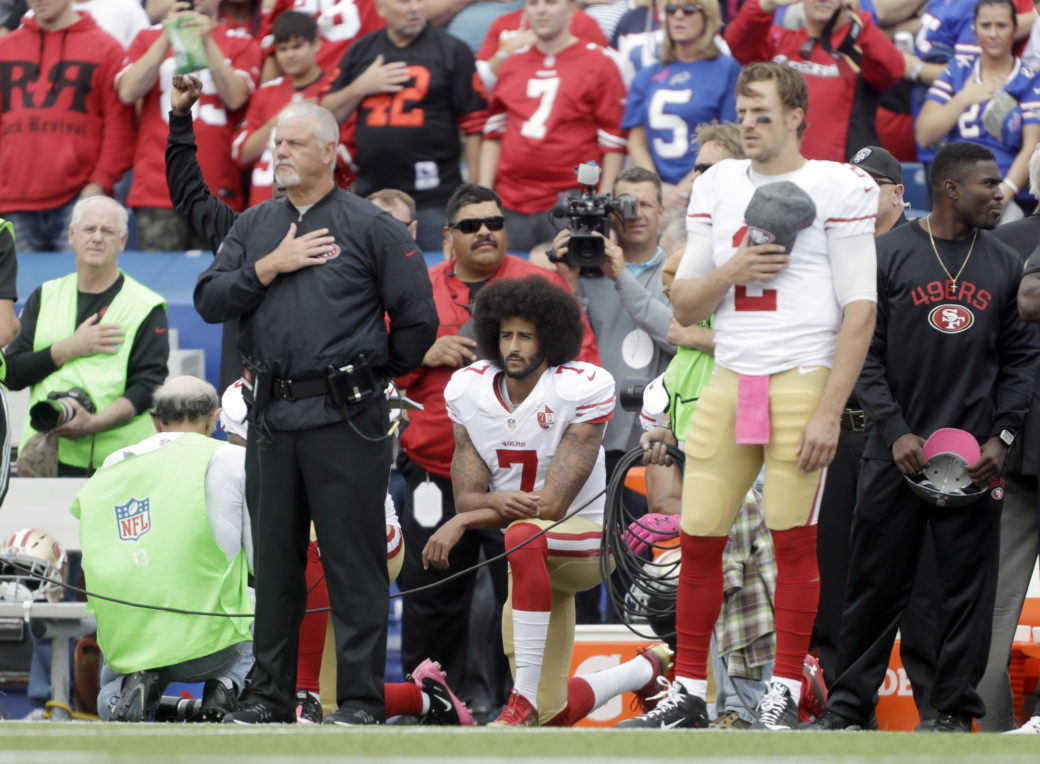

Some people responding to my celebration of NBA star Jonathan Isaac’s decision to stand during the national anthem while all around him took to their knees have (rightly) raised questions about how my post fits with Colin Kaepernick, the quarterback in the NFL who first took a knee during the national anthem in protest against racism in the United States.

Kaepernick’s actions developed quietly in the pre-season, and became more public and intentional as a result of then Republican candidate, now President, Donald Trump’s reaction to his actions. Trump has a long history of, at best, courting the white supremicist vote for his own political ends, not only through dog whistling tweets and soft responses to fascism (including his response to Kaepernick’s kneeling, but also around the NASCAR “noose” story earlier this year), and at worst, being a white supremicist by conviction.

In the washup of his decision to take a knee, Kaepernick said: “If they take football away, my endorsements from me, I know that I stood up for what is right.” Love it. Others didn’t. His actions were framed as actions against the Flag, against the veterans, against the civic religion of the United States — they were framed as a desecration of sorts. But, for Kaepernick, they were simply an expression of his convictions that something in the United States had to change before he could feel like he belonged.

While, in my last post, I suggested there’s a parallel between ‘taking a knee’ and adopting a posture of submission, or worship (the greek word proskuneo), one can also adopt a posture of idolatry or worship by standing for a liturgical moment in the cult of civic religion. Kneeling during the anthem can also be a rejection of an alternate vision of the good; an alternate idolatrous regime. Our bodies are instruments of worship, and their postures, especially habitual ones (like kneeling, or standing), form us.

Since my post about Jonathan Isaacs, Israel Folau, no stranger to not bending the knee to idolatrous social pressures, has also drawn the ire of the Twittersphere for failing to kneel before an English Rugby League game, where he plays for a French team. The way new shibboleths emerge, and the mobs who are willing to conduct spontaneous heresy tribes with cancellation looming large is one of the more visible expressions of how deeply religious our hyper-secular society has become; and how much we’re all aggressive monotheists rather than pluralists. The overlap, or faithful presence, of Christians within these movements is an interesting test of one’s political theology.

While the present pressure to ‘take a knee’ feels implicitly, if not explicitly, religious — a call to give bodily expression to convictions about truth and goodness, where those who don’t participate are expressing a rejection of an orthodoxy that leaves the crowd incredulous — the roots of the ‘taking a knee’ movement were also, essentially, Christian. In that Kaepernick is, by all accounts, a man of deep Christian convictions. His decision to take a knee in the face of injustice was a decision not to stand for the values of a country, or its flag, while that country and flag were symbols of oppression; of a sort of beastly Babylonian imperialism. As James K.A Smith puts it in Awaiting The King, politics is inherently religious, he says: “There is something political at stake in our worship and something religious at stake in our politics.”

In Smith’s system, which pays attention to embodied practices as ‘liturgies’ aimed to form us with a vision of the good life, the act of standing for the national anthem is not neutral, it is a civic liturgy. Smith says, of the modern civic religion: “It shouldn’t be surprising when an institution that wants you to “pledge allegiance” is not happy with anything less than your heart. In this case, a liturgical lens works like a cultural highlighter that draws our attention not just to the “laws of the land” or the decisions of supreme court justices but to the rites interwoven in our public life together—the rituals and liturgies that inculcate in us a national myth and habituate in us an unconscious allegiance to a particular vision of the good.” Our Australian equivalent is the civic cultic apparatus that has emerged around ANZAC Day and its mythology; a mythology that shapes the collective Australian psyche (and psyche is just the Greek word the Bible uses for soul). Smith suggests his lens is a useful one because it invites us to “be attentive to the ways we are formed by the rites of democracy and the market, not just informed by their institutions.“

Whether one stands or kneels during the national anthem is now loaded up as a civic-religious rite; one is either perceived as joining in and participating in the civic cult, or perceived as desecrating that valuable thing by participating in an alternative religion. And as we intentionally use our bodies in either direction, according to Smith, we are being formed towards some vision of life — then, when the Twitter voices pile on to either celebrate or condemn our actions, that formation process goes into hyper-drive. Our formation is amplified by the filter bubbles we belong to and their reinforcing interpretation of our embodied acts.

How are we meant to live, as Christians, when no public territory is religiously neutral? By being attentive, discerning, and acting with intent as people who belong to a different polis; the kingdom of God. As Smith puts it in his fancy phraseology: “our political engagement requires not dismissal or permission or celebration but rather the hard, messy work of discernment in order to foster both ad hoc resistance to its ultimate pretensions and ad hoc opportunities to collaborate on penultimate ends.” This is quite similar to what James Davison Hunter calls being a “faithful presence,” and is also the sort of leadership Edwin Friedman calls for in A Failure of Nerve, that of being a differentiated non-anxious presence in an increasingly anxious and fractious body politic. We’re to know who we are, such that we can resist being deformed or conformed to the patterns of this world, while seeking to be transformed, and to transform the world around us according to the picture of the kingdom of God revealed to us in Jesus.

Jonathan Isaac decided to not kneel, not because he rejects the idea that black lives matter, but so that he might make the case that racial justice won’t come through kneeling, or perhaps even politics, without the Gospel. His decision was an attempt to be a faithful presence, one differentiated from the world around him and its conforming patterns. In my piece unpacking his actions, celebrating them even, I hoped to qualify both that Christians can faithfully be present, kneeling even, in protest movements, and faithfully present in empires (think Daniel under Nebuchadnezzar in Babylon, and then under Darius, think Joseph in Egypt, think Erastus in Corinth). It wasn’t a problem for any of these individuals to contribute to the common good in an empire, despite the idolatry inherent in these empires, but there is a pressure that comes with this sort of presence; a pressure to bend the knee to idolatrous systems, rather than to king Jesus.

Sometimes this sort of faithful presence isn’t just about joining some sort of pre-existing empire, or political cause, Christians can even start, or lead, protest movements as expressions of our convictions about the nature of the kingdom of God, and the nature of beastly kingdoms set up in idolatrous opposition to Jesus. When Kaepernick first took a knee, the symbolic meaning of his refusal was clearly a repudiation of empire consistent with his faith. One of his (many) Christian tattoos features the words of Psalm 27:3, “Though an army besiege me, my heart will not fear though war break out against me, even then I will be confident.” His taking a knee, surrounded not just by players, but an empire, that first saw this as an attack, was an act of courage, coming from convictions he owns as a follower of Jesus.

Both Kaepernick’s kneeling, and Isaac’s standing, were acts of faithful presence. Like the paradoxes in Proverbs in the Bible, where the wise person either answers a fool according to their folly, or does not, the vexing moral issue of our time is captured, in some form, in the question ‘to knee, or not to knee’?

Does one take a knee in solidarity with a brother who sees the idolatrous impact of empire on his people, who refuses to put the nation state — the empire — in the place of God?

Or does one stand, because at some point the act of kneeling has become synonymous with alternative forms of empire, and a religious social pressure just as opposed, ultimately, to the truth of the Gospel as that which it kneels against?

The key is that whatever you’re attempting to do as a faithful presence, your posture reveals a faith in Jesus as king, not in the alternatives; which will mean freedom to do either, and will require charity from within the body of Christ to be directed at those exercising wisdom and freedom in a different direction; not an attempt to eradicate our fellow Christians as repugnant others in a culture war.

This ethical conundrum became a little less clear cut when Kaepernick’s symbolic act was co-opted by two essentially religious groups. First by Nike, in order to sell more shoes through that insidious form of capitalism. This sort of capitalism is the kind where a multi-national company that has a history of using oppressed people to make shoes in the third world for peanuts, can simultaneously make a poster boy out of a member of an oppressed group who took a costly stance on racism to sell more shoes. It’s here that we might note that what often gets called ‘cultural marxism’ is really just another lever pulled by the capitalist machine to sell goods to a different audience, an idea you can dig into further in The Eucatastrophe’s episodes on cultural marxism. And second, when it was co-opted by people wielding essentially the same but reversed, political power against the (racist) empire as an expression of a culture war with a merchandising arm. Those campaigning against racism, and for the dignity of black lives, are certainly more aligned with God, as creator, and the kingdom of God, as the ideal, than those seeking to uphold white supremacy through systemic racism, but there’s an insidious idolatrous agenda, built on worldly power being applied without God in the picture, co-opting this kneeling campaigning, and twisting potential solutions to racism away from the truth, and towards the idolatrous status quo, just with different labels. Whether BLM or Nike, whether one kneels or stands, as in so much modern politicking, the forces of ‘the market’ are in the mix attempting to make more money through social and political posturing. One wonders who is making and selling the shirts that NBA players are wearing during the anthem…

Modern capitalism (surveillance capitalism or otherwise) is just like modern black-hat Russia in its manipulation of discord in western elections; it doesn’t matter which side wins, so long as the fight is happening in a destabilising way, if that happens, Russia wins. Modern capitalism is like the arms dealer in the culture war, selling polarising political-religious iconography to both sides, turning a buck, growing the market, conscripting us not to our political theology, but to Mammon. How dare Isaacs not wear the Black Lives Matter T-Shirt (he did still wear his Orlando Magic shirt, which you can buy in the gift shop for…). Mammon doesn’t care so long as you buy your political merch and wear it loudly in performance of your virtue; the louder and more obnoxiously the better, in order to promote an equal, but opposite, reaction (and more sales).

When the market turns activism into a way to make a buck or two, we should be doubly suspicious of its religiosity; these acts then serve the twin idols of our vision of the political good (our idealism, or empire), and the economic machine. Black Lives Matter is increasingly a monetised social media phenomenon with merch. Kaepernick’s kneeling became a Nike campaign putting “overt” into religious overtones.

Now, to not kneel, but to stand, is its own act of rebellion, or subversion, in the face of another conforming pattern of this world; and it’s unclear whether by standing one is upholding the idolatry of empire, rejecting the capitalisation of activism, rejecting an anti-racist political movement that is, itself, potentially idolatrous, or simply standing as an expression of faith in an alternative kingdom, with its king.

And here’s where Smith’s diagnosis of the modern ‘political field’ is useful; global capitalism means politics isn’t just about the government; it’s not just about a political empire, but also an economic one, our governments increasingly become pawns in an increasingly global idolatry; the worship of Mammon, and the church, or kingdom of God, stands in opposition to all these forces. Smith describes this, again this is from Awaiting The King:

“If the church is a “public” that stands, in some sense, counter to the pretensions of the earthly polis, we can’t narrowly mistake this as a critique targeted only at the state because, in the current configuration of globalized capitalism, the state has in many ways been trumped by the forces of the market and society. Wannenwetsch points out that in Western societies—and globalized societies more and more—the economy functions as a “structure-building force” that shapes everything. The market now constitutes “the inner logic” of society itself: the dynamics of society are “moulded by the laws of the market: as a contest between participants competing for an increase of their shares.” This coupling of market forces and the crowd’s demand for publicity means that everyone dreams of monetizing their Instagram feed. And that effectively becomes the ethos of a society.”

This ethos is on display in a protest movement that is essentially performed for photo opps, and that arose from social media activism, using a hashtag. How can we possibly know if every knee publicly bent is a knee privately committed, as part of a body, to the renewal of society around the issue of race. How many knees bent in public, and knees belonging to people whose behaviours and ideologies in private, or out of the camera’s gaze, are given to maintaining the status quo? Isaacs was right to emphasise the need not just for a change of actions, but of hearts.

How one decides what to do when such pressure is applied, and the stakes so high, is an interesting shibboleth test for life in the modern world. Navigating this sort of climate, where nobody is prepared to give an inch in the culture war, but all acts are interpreted through a hyper-political lens, is almost impossible, and certainly crippling. The key for us Christians is to use our bodies in ways that align with our story — our understanding of their God-given and redeemed purpose; our trajectory, or, as Smith puts it, our ‘teleology,’ which “is an eschatology: a hope for kingdom come that arrives by the grace of providence and doesn’t arrive without the return of the risen King. And this changes everything. A teleology that is at once an eschatology will be countercultural to every political pretension that assumes either a Whiggish confidence in human ingenuity and progress or alarmist counsels of despair. But precisely because Christian eschatology is a teleology of hope, it will also run counter to cynical political ideologies of despair that reduce our common life to machinations of power and domination. Furthermore, a Christian political theology attuned to eschatology will run counter to a kind of postmillennial progressivism to which the so-called justice generation sometimes seems prone…”

Any action, or story, that does not share this teleology or eschatology is essentially idolatrous, which isn’t to say we can’t participate in public alongside people who do not share our worship of Jesus, but simply that we should be careful that the use of our bodies is aligned to the truth, not to truncated visions of what it means to be human, and how to solve the problems we’re confronted with in a world marred by sin.

So, Christian. Kneel in the protest movement against racism, or stand against solutions to racism that don’t include king Jesus. Do so as a faithful expression of obedience to your Lord Jesus. There’s freedom here, and this is a course that requires wisdom — but don’t be so co-opted by worldly agendas whether of ‘political empire’ or ‘economic empire’ (and really, these are just two sides of ‘Babylon’) that you lose sight of what is ultimate. Don’t crucify your brothers and sisters for choosing a political action that is different to yours, but celebrate when ambassadors for Jesus are able to be a faithful presence in any community, pursuing the goodness, truth and beauty of the kingdom.

Because remember, ultimately, there is no choice about bowing the knee; we’re all going to take a knee as we participate in various non-ultimate realities here and now, and those realities are going to be religiously motivated economies, like Egypt, Babylon, and Rome were, but every knee will one day bow to Jesus. And it’s his kingdom that counts, and his rule that offers a solution to the problems of sin, including racism. This is part of that ‘eschatology’ — that future hope — that Smith talks about, a future secured through the death, resurrection, ascension, and future return of Jesus:

Therefore God exalted him to the highest place

and gave him the name that is above every name,that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow,

in heaven and on earth and under the earth,

and every tongue acknowledge that Jesus Christ is Lord,

to the glory of God the Father. — Philippians 2:9-11

As you choose who or what to bend your knee to now, bend it to him. It’s good training.