Eternity News published a piece from James Macpherson today that’s the latest in a string of articles from white blokes, typically in positions of leadership or influence in the Institutional Church, waxing lyrical about the state of affairs facing Christians in Victoria; specifically the circumstances facing (typically blokes who are) leaders in church communities in Victoria who may transgress the new Change and Suppression (Conversion) Therapy bill in Victoria.

I’ve lost count of how many people disclaim their objections to this Bill by pointing out that they — like everybody else — don’t believe in aversion therapy or electric shock therapy — the archaic forms of clinical practice employed by therapists when homosexuality was considered a psychological disorder, in the professional field of psychology and psycho therapy (the manual of psychological disorders the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association only removed homosexuality from its list of diagnoses in 1973). So here, for example, are a couple of these disclaimers from prominent blokes with institutional influence, starting with the piece from Eternity (which also ran, in an expanded, and more terrible form, at The Spectator; it’s a culture war piece more at home on Caldron Pool):

“We were told that the Change or Suppression (Conversion) Practices Prohibition Bill, passed by the Victorian government last month, was to stop archaic practices such as electric shock therapy being used on gay people. The legislation has deliberately sought out voices that insist conversion therapy is not simply some wacky pseudo-psychological practice that has fallen by the wayside, but standard church practice and teaching.”

Or…

“The Bill is so hopelessly sourced, and – despite its claims to be targeting what is ostensibly a unicorn, – namely pseudo-spiritual conversion therapy techniques that are rare and indeed extinct – is intended to fire a shot across the bows of churches that take a traditional and orthodox line when it comes to sexuality matters.”

Or…

“For example, it wasn’t that long ago that aversion therapies were taught at a university here in Melbourne and practiced by doctors. Second, contrary to rhetoric offered by the Government and activist groups, conversion practices (ie aversion therapy) were always rare and unusual in religious settings. These are groups who blindly followed what was considered mainstream science at the time. However, instead of limiting legislation to banning an archaic practice that everyone agrees is wrong, the Parliament has outlawed praying and even talking with another person about sexuality and gender.”

Or…

“There is nobody who supports or condones the sort of coercive “gay conversion” practices which might have occurred in the context of psychological treatment and some faith communities in the middle of last century. Such practices are abhorrent.”

Lyle Shelton and Martyn Iles both provide caveats in their public objections to the Bill along these lines too; it’s the almost essential disclaimer because everyone agrees that zapping away the gay is beyond the pale; they just aren’t sure if we should be able to ‘pray away the gay’… But the idea that the Bill is targetting something abhorrent, and slipping in a bunch of ‘normal’ Christian practices (that aren’t harmful at all) is a common objection to the Bill. There’s a sort of widespread incredulity that the government would go after much more nebulous church practices beyond these overtly harmful practices; and there’s often a commitment to small government driving these objections (a suggestion that this is an illegitimate use of power). Whether that small government objection is right or wrong is an interesting question, it’s one I personally have sympathy for — except, that I think we welcome government intervention in areas where we genuinely believe harm is happening, so this objection actually sits on a fundamental belief that run of the mill Christian culture and practices aren’t harmful for Gay people; which is to say, these voices don’t believe the stories behind the Bill, that produced the broad brush approach.

I wrote a piece for Eternity with my student Minister Matthew Ventura (you can read his thoughts about life as a celibate gay Christian at singledout.blog), where we suggested believing the stories of harm would be a great first step for us Christians. In the course of writing this piece, we spoke to a few other friends, including another celibate gay Christian, Tom Pugh, who has been involved in ministry with a conservative evangelical organisation (you can read Tom’s excellent insights at Transparent).

Tom made a point that became a paragraph in our piece, saying:

“There’s something about the theological system and ministerial structure/practice that seems to produce what you might call spiritual codependancy. When taken as a whole, the preaching and practice of a church can, to a certain kind of person, function in a way that is effectively coercive.”

This insight — and Tom is not alone in expressing this view — is, I think, part of the picture that more conservative ‘small government’ Christian figures with institutional influence are missing; and there’s a couple of analogies I’d like to draw in order to plead with my brethren (and it is, so far as I can tell, exclusively blokes who keep making this point); because I think it’s a point that is a product of privilege (both institutional, and from the individual experience of being a cisgendered, heterosexual, bloke).

I wrote recently about an article by Michael Emerson on racism that made the point that white people tend to think individualistically about race, while people of colour tend to think collectively, and further, that: “Whites tend to view racism as intended individual acts of overt prejudice and discrimination,” while “most people of colour define racism quite differently. Racism is, at a minimum, prejudice plus power, and that power comes not from being a prejudiced individual, but from being part of a group that controls the nation’s systems.” This disparity in thinking, I think, is actually a right/left distinction as well as an individual/collective cultural distinction — the ability to think about systems and the power (sometimes oppressive, harmful, or coercive) that systems wield. This maps on to the objections about conversion therapy legislation that broaden the definition from overt acts of conversion therapy to attempts to tackle the harm caused by coercive systems. You could frame it as ‘conservative Christians tend to view conversion therapy as intended individual acts of overt violence and harm,’ while the government (and those reporting stories to them) ‘define conversion therapy quite differently. Conversion therapy is, at a minimum, prejudice plus power…” you see what I’m doing there… it’s the same dynamic. Arguably it also works with feminism and other stuff that forms the whole ‘critical theory’ approach to ‘whiteness’ and ‘wokeness’ and intersectionality; that is, when you’re the beneficiary of an institution or status quo, when you’re ‘the norm,’ you can be blind to the dynamics that don’t directly effect you, but perpetuate your position in that system. Like, you know, the Pope and the church establishment when Luther started trying to bring systemic reform.

There’s no coincidence that this particular objection about the prescriptive definition of conversion therapy being broadened to something nebulous comes from typically right-thinking men who experience institutional influence (also, to be fair, those perhaps most at risk of transgressing the legislation). It comes with a particular understanding of the world; one that may or may not be objectively true; but is, I’d suggest subjectively likely that they will hold that position based on the privileged position they typically occupy in the institutional church. I’m aware that this sort of claim can be quite triggering to conservative blokes, in conservative institutions, who think individually not just systemically, because my default is to be those things.

And here’s the questions I’d put to those mounting this argument against the legislation (whether or not the legislation is good is an entirely different question), and one that I have covered previously.

a) Are you in favour of government intervention in church practices around both systemic issues and particular practices on child safety, especially after the Royal Commission?

b) Do you think steps being taken by governments to legislate against ‘coercive control’ in the context of Domestic Violence are good and necessary?

The reason I think these questions are worth pondering is that I think there’s a direct line between both these questions and Conversion Therapy legislation.

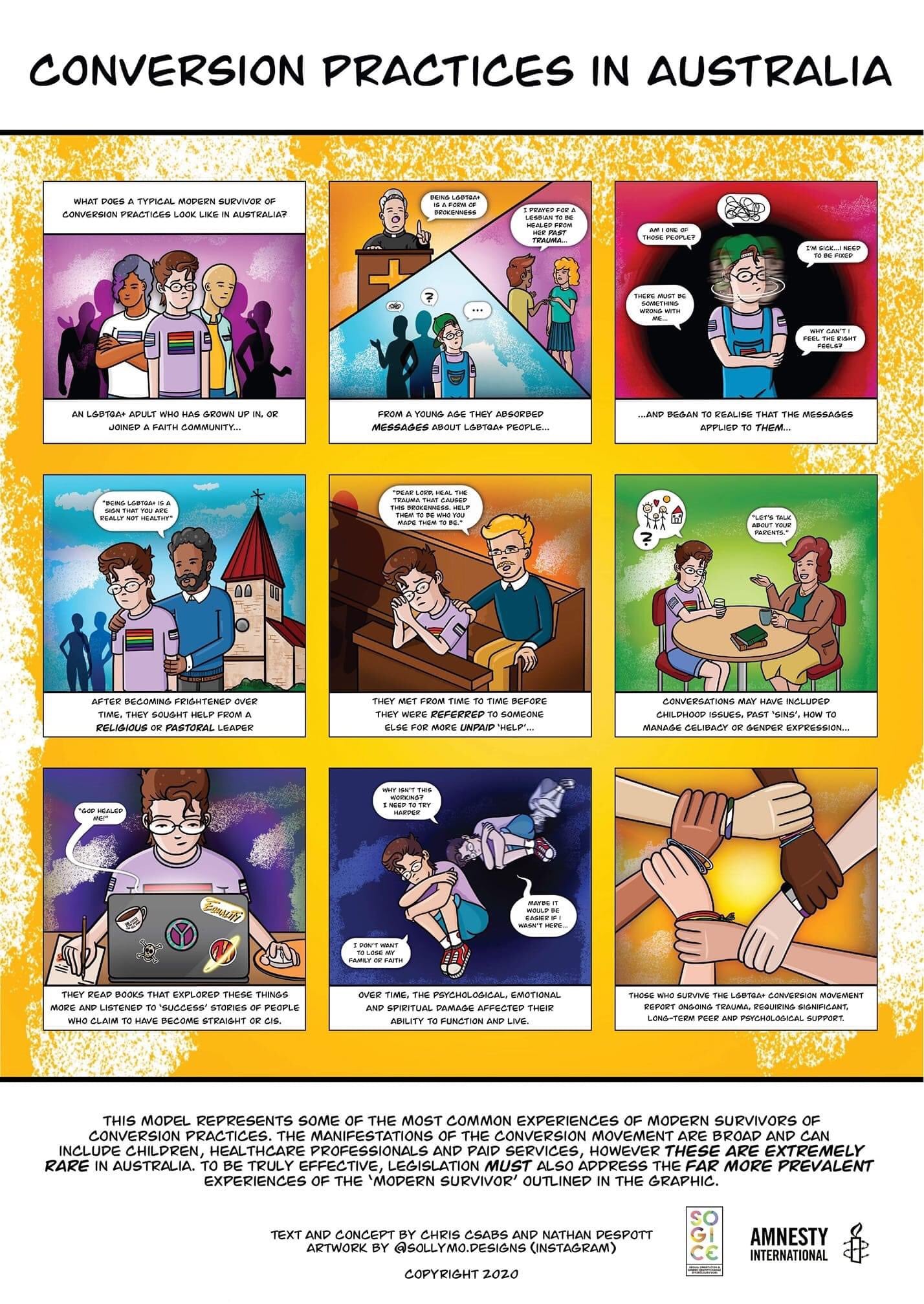

The research supporting the Bill in Victoria involved hearing real stories — it didn’t have the scope, or the national reach, that the Royal Commission had, but the stories of those who had been harmed by practices beyond just ‘archaic unicorn’ therapies were believed; and, even those people still in our church communities, committed to celibacy, would say there is a system or culture at work in the church that is harmful; and that often involves the sort of things that enlightened conservative individuals don’t themselves practice (or that their church communities don’t practice), but do defend (like Margaret Court’s ‘tin ear,’ or Israel Folau’s tweets, or practices that are cultural, rather than individual, around the view of homosexuality or the treatment of LGBTIQA+ people in our communities; I had, for example, an older Christian tell me this week that the country started falling apart when homosexual practice became legal); there’re a bunch of other things our Eternity article points to to fill this out some more.

If these practices do cause harm the legislation might be a clumsy, blunt, overreach, but at least it is trying to tackle something — like child safety — we should’ve been dealing with ourselves. I recognise that there is a push to attack any reasonably orthodox teaching that suggests homosexuality is, like many forms of heterosexuality, impacted by the fall and so both sinful and ‘broken’ (I also note that my own denomination, here in Queensland, believed ‘brokenness’ was too soft when it came to finding language to articulate this, and that those of us who use it had ceded too much).

The research around ‘coercive control’ and family violence demonstrates that abuse is not limited to particular incidents of physical assault, or even of verbal abuse, but that the relationships that can culminate in extreme violence — even murder — involve harmful dynamics that aren’t presently ‘illegal’ or even just ‘particular actions’ but do follow a recognisable pattern. Jessica Hill’s See What You Made Me Do is, I think, required reading on Domestic and Family Violence. I think Hill’s work profoundly and cogently makes the case for some government intervention on coercive control, as nebulous as it is. Even if it’s not currently dealing with acts of physical violence that are currently illegal; this is, in part, because I think trauma is real harm; and that it impacts the body and psyche as profoundly and deeply as physical violence (see, for example, The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van Der Kolk). Hill makes some observations about the dynamics of abusive, coercive, relationships that might also be true of coercive systems, she identifies ‘three primary elements’ at the heart of coercive control: “dependency, debility, and dread.” Now, note that my friend, without making these links, describe Christian culture — particularly life in conservative institutional Christianity — as creating “a spiritual codependency.”

Gay, or Same Sex Attracted, people growing up in Christian communities where the sort of ‘culture’ we typically hear minimised, or marginalised as ‘not what good churches do’ describe developing cognitive dissonance as a survival technique; the sort produced by the dread of being exposed as something other than the Christian norm — or, that if one was outed, this might include being outered — excluded from family or church family life. That dread, in itself, can become coercive and forms the ‘system’ behind conversations that might seem like harmless ‘pastoral’ offers of prayer or support.

The scientist Hill draws on, Albert Biderman, observed the ‘coercive control’ practiced by North Korean soldiers who had imprisoned US Prisoners of War, and suggested their practices included “eight techniques: isolation, monopolisation of perception, induced debility or exhaustion, cultivation of anxiety and despair, alternation of punishment and reward, demonstrations of omnipotence, degradation, and the enforcement of trivial demands.”

Now, churches don’t practice all of these when it comes to LGBTIQA+ people in our communities, or families, but some of these line up with real stories from real people, both in the Victorian research behind the Bill, and in stories I hear from my celibate gay Christian friends. In the context of domestic violence, coercive control can include policing things like language and dress, enforcing ‘cultural’ or community standards around language; limiting who people can or can’t see and speak to, controlling how time is spent, and seeking to modify behaviours that someone (the coercive controller) is uncomfortable with. Hill reports that the parallel between coercive control in POW camps and in DV situations has been observed since the 1970s; and in the earliest research making the link “survivors insisted that [physical violence] was not the worst part of the abuse,” the coercive control was more damaging. This might be, by analogy, the case with same sex attracted people in our communities — it may be that the most harm is experienced not in ‘aversion or shock therapy’ (violence), but in the system or culture that leaves them traumatised and having to navigate a culture filled with trauma reminders (or triggers) that compound the damage, and the sense of shame (the opposite of a sense of belonging).

This friend I spoke to, Tom, said the cognitive dissonance he experienced growing up in a church community produced “anxiety and depersonalisation” for him; depersonalisation being a ‘trauma based coping mechanism’. Tom was keen to reiterate that he doesn’t believe the culture he grew up in was operating maliciously, he observes that LGBTIQA+ individuals who grow up in church communities, especially as the broader community becomes more welcoming, can experience trauma, mental health challenges, and a sense of shame that come from navigating a culture or system that coercively ‘suppresses’ or ‘converts’ more of their personhood and experience than is necessary in order for them to faithfully uphold orthodox teachings on sexuality, and belong in traditional church communities.

Now, my point is not to say that standard church practices are a form of coercive control, and thus necessarily abusive — but that the stories shared by LGBTIQA+ people who have been harmed by church environments and practices aren’t being dishonest, and nor are governments, simply because the ‘unicorns’ of aversion or electric shock therapy are no longer practiced. Standard church practices might actually be harmful, and might not be necessary, so it might be legitimate for governments to expand their interest and care beyond ‘violent’ intervention or actions, into systemic and cultural practices; especially post-Royal Commission. Until we grapple with this — especially when we’re talking to left-leaning governments who think in ‘woke’ ways about intersectionality, privilege, and systems — we’re talking past those making the laws.

If our practices are causing actual harm, and we could do better — it’s on us to make the distinction between child safety regulations and conversion therapy regulations; and at the moment just saying ‘but we’re not zapping someone’ isn’t actually engaging in the conversation on its terms; or recognising that harm can come from more than just ‘particular’ actions, but can come from coercive or controlling systems and cultures that dehumanise and dominate.