This week a Christian organisation, The Bible Society, hosted a civil conversation featuring political disagreement between two members of the political party who, at least in the short term, will be the people who determine the future of marriage in Australia. It featured some cross promotion with Aussie beer company, Coopers, who were going to release some special edition beers in support of the Bible Society’s 200 year anniversary. And the world exploded. Coopers backflipped on the deal. It’s a real brewhaha (sic).

Disclosure: I write for the Bible Society’s Eternity Newspaper. They’ve paid me for some stuff. I like them. I like the video (though I think it has some issues). I know the host, and like him. I think public civility is really important.

You’d be forgiven, reading the response pieces around the Christian blogosphere (and the outraged responses in comments sections and the Coopers Brewery Facebook page) for thinking that the world as we know it is ending (or has ended), and that we find ourselves in some sort of (un)brave new world. I don’t think it’s the end of the world, but I do think this episode is truly apocalyptic.

apocalypse (n.)

late 14c., “revelation, disclosure,” from Church Latin apocalypsis “revelation,” from Greek apokalyptein “uncover, disclose, reveal”

An apocalyptic text doesn’t really describe the ‘end of the world’ (not primarily), it reveals the world as it truly is. And that’s what has happened this week; the discussion around this video has been revealing both when it comes to the church, as we speak about issues our world disagrees with (and about our expectations about speech), and about our part of the world and its religiosity. Because what’s going on is really a clash between religious views of the world. A clash between the religious, the irreligious, and those who are fundamentally religious without realising it.

The religion of a section of the Australian left treats heretics with the same sort of sympathy that the church has, historically (when the church has been closely linked to the state and able to punish with the full force of the law); which is to say it seeks their utter destruction. Just ask Coopers (or read the one star reviews on their Facebook page, and see the pubs that are moving to quickly distance themselves from the company). And the thing about these moments of revelation is that they’re actually ‘apocalyptic’ in a true sense; they pull the curtain back and reveal the world as it really is, and give us a sense of the future as it could be. Stephen McAlpine’s posts on this story are worth a look (yesterday’s, and today’s), and ultimately his conclusions from the wash-up today look a bit like mine. Only I’m more hopefully optimistic about things than he is.

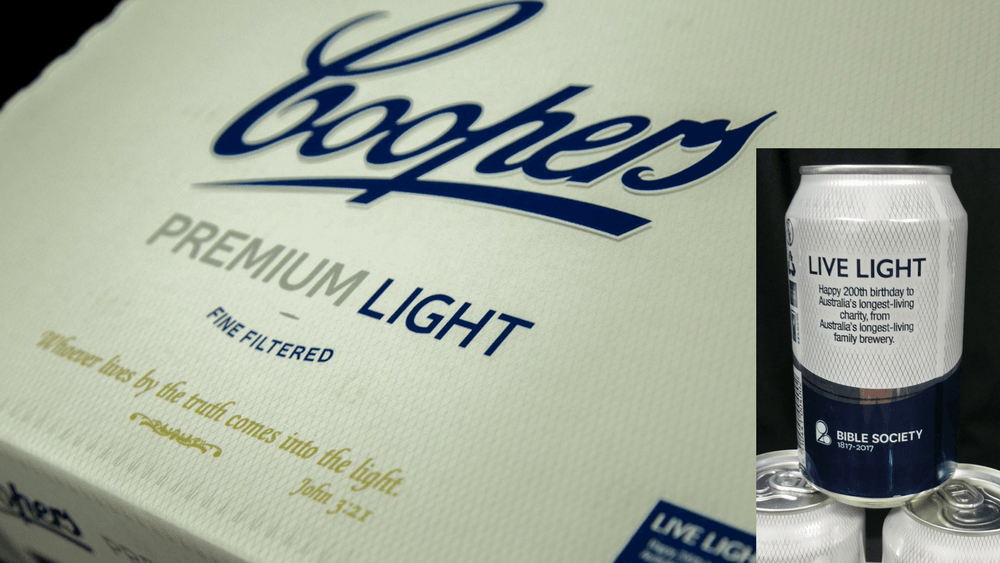

The conversation itself featured two politicians — a gay agnostic, and a Christian conservative. These white blokes trotted out well worn arguments for and against a change to the definition of marriage in Australia over a light beer in a product crossover that has copped some flack. What was remarkable was that they were attempting to model civil debate, that they listened and disagreed respectfully. What is even more remarkable is what the fallout reveals about the end of the world as we know it. Twitter went nuts. Coopers was flooded with one star reviews on its Facebook page, accusations of homophobia (for a video they didn’t make, that featured a gay man who will potentially be the most effective advocate for marriage equality if the Lib/Nats move towards a free vote), and boycotts from individuals and pubs. Coopers released three statements; one in favour of dialogue on the issue, one distancing themselves from the video, and a third and final statement capitulating and signing up as paid up members of the marriage equality movement. They’re also pulling the release of the Bible verse beers… the Bible Society has been criticised for featuring two liberal MPs, but this criticism seems to miss the point that only Liberal MPs think this issue is possible to discuss anymore…

Personally, I’m tired of the idea that marriage is a zero sum game; that we (as Christians or conservatives) can only conceive of an approach to marriage that is a binary ‘no gay marriage’ or ‘gay marriage’ — this is where most of the anger seems to be levelled at us. Why we can’t do pluralism well and figure out ways to acknowledge the religious import of traditional marriage for some Christians, Muslims, Jews, etc, and protect that for both institutions and individuals within the community, while also acknowledging the religious import of changing the marriage definition for those who do not worship a god at all, but individual freedom, is beyond me. That’s my disappointment with the ‘debate,’ and why my position is closer to Wilson’s than Hastie’s.

Here are some things I think this episode reveals about the church and the world.

1. Our failure to practice listening as Christians means later attempts at ‘civil conversation’ fall on deaf ears

In terms of revelation, this reveals a certain degree of ‘out-of-touchness’ when it comes to Christians in Australia and our sense of just how distant our assumptions are from some people around us. That this video seems quite reasonable and good to us but to others is the stench of death (and the sort of thing that certain people believe should lead to the death of Coopers). If people are shocked by the vicious outrage in response to the video it probably represents how far removed some people advocating for traditional marriage are from the lived reality of those arguing for it.

There has been a tendency in some corners of the church — some that I move in — to suggest that we do not need to listen to, or understand, those asking for same sex marriage. Our job, we’re told, is simply to speak ‘God’s truth to the world’ not to listen to sinners or understand what they want; I can point to specific examples of this in the Presbyterian Church of Australia, and I’d say a new Sydney Anglican website on same sex marriage also does this when it employs slippery slope arguments and just generally fails to listen to what people on the other side are actually asking for and why, while ‘speaking faithfully’. The Bible Society is doing something different and commendable in this video, but it can’t escape the baggage of the Christian brand at this point.

It is possible that if the church continues apparently not listening our own speech will be treated the same way by those who disagree with us (and I think that’s happening), so it was nice to have this circuit breaker that said “hey, we’re not afraid to listen to a guy who disagrees with Christians, or even to give him a platform and share his thoughts with Christians all over the country”…

Our engagement in this debate as the church has involved a failure to listen, and so our arguments always feel like non-sequiturs, or nonsense, to the ears of people who have totally different understandings of what it means to be human. From where I stand, there has not typically been much sympathy for the desires of same sex marriage supporters or their view of the world; we’ve tended to impugn the motives of those asking for it, to see a bunch of other potential changes being ‘freighted in’, to be fearful of our own place in society, and there hasn’t been a real attempt, by Christians, to grapple with how our moral vision fits in a pluralist, secular, society where many of our neighbours don’t believe in God so reject the natural law arguments we serve up (Hastie offers a conservative, natural law, argument for maintaining the traditional definition of marriage).

This means it feels like we’re not interested in listening to, or understanding our neighbours, which means it seems disingenuous for us Christians to be making the case for civil discussions of the issue now. The great irony here is that we have a Christian organisation also giving a platform to a conservative case for same sex marriage from someone who is on the record as being sympathetic for a range of religious freedom concerns. If I was a non-Christian I’d be celebrating that a Christian organisation is providing a platform for that sort of view, and a conservative Christian politician is modelling actually listening.

2. The church needs to figure out how to operate in a pluralistic world… and fast

This video from the Bible Society was a nice example of a step towards pluralism. It doesn’t actually pick a side in the marriage debate, despite what those who’ve already settled on changing the definition of marriage might tell you. If we can’t figure out how to operate in a pluralist, secular, democracy then we can expect much more of the sort of treatment Coopers got from this video. And it’s not so much Hastie’s position (though he’s a Christian) that reveals the problem here, it’s a thoroughly consistent conservative position; it’s the ongoing sense that the future of the church’s witness, or our position in society, depends in some way on how this debate goes; it’s that the video presents the options on marriage as a binary choice between legislating same sex marriage, or maintaining the conservative position. This binary lacks imagination and backs us into a corner; if we can’t advocate a generous and pluralist solution to those opposite, then we can’t very well turn around and ask them for a pluralist solution (religious freedom) if/when they win. When it comes to same sex marriage it doesn’t have to be a choice between Wilson and Hastie.

Every belief about marriage is a position derived from a type of ‘religious’ conviction (a ‘theological anthropology’ even). A belief that there is no God brings with it a certain account of who we are, and opens up a range of potential visions of ‘the good human life’ — our ‘religious beliefs’ shape our understanding of what is and isn’t good for people. For the theist, the ‘good’ is the personification of the nature of God, for the non-theist the thing that acts as ‘god’ (a sort of organising force in the world) is the deification of the ‘good’ (in the case for same sex marriage the ‘divine good’ looks like love and individual freedom). We’re not good — many of us (Tim Wilson is an exception) — at accommodating different gods, or visions of ‘the good life’ in a shared political framework.

3. We need to be slow to overreach in our reaction to the reaction, because the outrage cycle is built on perpetual overreach

It’d be a shame to over-reach though, in terms of what the reaction to this video represents for us as the church. We’d need to do a good and careful job at parsing out exactly what people are angry at, and why, and whether they’re angry at Christians speaking at all, or angry because of the way Christians have spoken out on this… and we need to ask ourselves some pretty bracing questions if it’s the latter (and I think it could be, in part because as a Christian looking at how we speak about marriage, I think we’ve often got this wrong).

The thing about the outrage cycle is that it often involves a tit-for-tat ‘hot take’ driven over-reach, and there’s not always enough time given to that careful analysis of what is happening and why (this tends to be diminished the more somebody has been developing a systemised approach to understanding something more broadly, when it’s possibly a response to ‘data’ rather than anecdote).

We might be tempted to describe this as the death of free speech in Australia. It could be. Free speech is definitely under attack from a certain section of the Australian community; and the attackers do have some politicial clout. I’ll suggest below that Christians shouldn’t be into free speech, but costly speech, anyway… but I think it’s a mistake to think that the chattering class (who can be found writing opinion pieces, blogs, and comments below the fold on these pieces) represent the whole Australian landscape. It certainly doesn’t seem to value Tim Wilson or see his perspective as one shared by those outside a particular intellectual circle. I spoke to someone yesterday who had reached out to Tim Wilson to see how he was coping with the fallout, and he’d remarked that the outrage simply proved his point. Not everybody in this world, outside the church, finds outrage appealing (just as not everyone in the church wants to join in the outrage but from the opposite end).

It’s possible that the hardcore, reactionary left is massively over-reaching in its response to this video (and Coopers is over-reacting, and responding far too quickly in response to this over-reach). I’ve written lots about marriage and same sex marriage, I haven’t hidden my Christian convictions, and yet I manage to have pretty robust and civil conversations with gay friends, my neighbours, my friends from the left, and friends from the right. The hard left gets a disproportionate and distorting influence on certain issues (including marriage) in the Labor Party, just as the hard right gets a disproportionate influence on certain issues (including marriage) in the Liberal Party.

I do think our problems, as the church, are more about a failure to listen, a failure to do pluralism, and some problems when it comes to what we say when we speak… I don’t know many people in the real world who planned to change their beer buying habits as a result of this campaign; I don’t know many people who have the sort of spare time that allows them to fill up the comments sections on different websites, or write one star reviews. We need to be careful not to over-react, in fear, to a noisy minority (while being careful in how we engage) because that actually serves to amplify the voice and impact of the over-reachers.

4. The new religion of the secular left learned how to treat heretics from the best… the church

In the 14th century there was a guy, John Wycliffe, who dared to translate the Bible into the language of the people. The church felt like its power was threatened by this dissenter. Sadly he died before they could kill him. So the church dug up his body and burned him. In the 16th century there was a guy named Servetus; his teaching was heretical and considered dangerous. Calvin reluctantly worked with the government of Geneva to have him executed. When religion co-opts political power, bad things happen to ‘heretics’… the state religion destroys them. The state hasn’t destroyed Coopers in this case (and the future of Coopers remains to be seen), but the treatment of the company, and its business, at the hands of their critics looked a lot like a witch hunt, a lynching, or a heresy purge. It remains to be seen whether Coopers’ repentance and contrition will save them — it would’ve saved a Christian in Rome, if they’d just chosen to bend the knee to Caesar… but it feels like the online outrage machine is less forgiving than Rome, and it’s certainly less inclined to forgive than Calvin was with Servetus. There isn’t much space for grace in the ‘gospel’ of the hard left. Just shame and destruction. The more we point that out not just by decrying it, but by modelling a compelling alternative, the better…

5. We need to tighten up our speaking; sometimes we can try to be too clever and homophonia gets us in trouble

The Bible Society has, for some time, had the slogan ‘live light’ as part of its brand. But its playfulness and lack of clarity about what ‘light’ is, has bitten pretty hard this week.

In its mission statement is says:

“Early in the life of Australia, passionate community leaders like Lady Macquarie created the Bible Society. They knew it wasn’t just government that could build a nation. It would need people of hope, people who live light.”

Indeed, its logo prior to this bicentenary celebration was this…

It’s not (though the tone of the video might suggest otherwise) really about treating the issue lightly (as though they don’t matter or should be laughed off); the two people conversing are very serious stakeholders in this debate mounting serious arguments for their position. It’s about bringing ‘light’ not darkness.

The bit of the verse featured on the Coopers carton in the picture above (a ‘light beer’) says:

“Whoever lives by truth comes into the light”…

That’s, of course, not the full story. It leaves ‘light’ a bit ambiguous. The verse that is, in part, featured on the Coopers cartons that support the campaign is John 3:21:

But whoever lives by the truth comes into the light, so that it may be seen plainly that what they have done has been done in the sight of God.

This is about light as opposed to darkness; not light as opposed to ‘heavy’ (as in beer), or light as opposed to serious (as in discussion)

The context of this verse is:

This is the verdict: Light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil. Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed. — John 3:19-20

This verse is ultimately about Jesus. Coming to Jesus. Jesus is the light. He’s not darkness or watery beer.

Bible verses don’t work so well if we pull them apart and lift them from their context. And it’s especially dangerous to take a word like ‘light’ and be flexible with the definition for the sake of a clever campaign. Biblically, in the Greek, light in weight is ἐλαφρός while light as opposed to darkness is φῶς. It’s not a great bit of word play to let the definitions creep into each other. It’s confusing.

That the public conversation is now about how wrong it is for the Bible Society to treat such a significant conversation lightly shows that we have a real problem, in our culture, with homophonia. When words sound the same, we take the least charitable possible understanding in a way that serves our own purposes. But it doesn’t help when the people speaking are obscuring the charitable understanding they should be promoting… Sometimes we try to be too clever with slogans — so when we have ‘a light discussion about heavy issues’ in connection with a Bible verse about Jesus, that can catch us out. Mixing metaphors gets us into all sorts of trouble, and this campaign mixing a Bible verse, light beer, and a light hearted conversation is a bit confusing for all of us.

6. The Bible has useful principles when it comes to public civility; but its point is usually about something much more important than that

The video is meant to promote the idea that following the Bible’s advice when it comes to disagreement produces better outcomes (I think it does). It’s part of the Bible Society’s campaign to show how the Bible brings light to the world. What the video was meant to demonstrate, or reveal, is that it is possible that living in the light of the Bible, and its wisdom, produces better, more civil, conversations in public about significant issues. The way Wilson and Hastie attempted to model advice from the book of James does seem to demonstrate a virtuous type of public civility that I desperately crave in and for our nation. It’s not that the Bible alone produces this civility, Wilson isn’t a Christian, but the Bible does, or should, produce people who do this. The fuller context of James 1 says:

“My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry, because human anger does not produce the righteousness that God desires. Therefore, get rid of all moral filth and the evil that is so prevalent and humbly accept the word planted in you, which can save you.

Do not merely listen to the word, and so deceive yourselves. Do what it says.”

Now. I’m sure that being quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry is good advice for civil conversation. But really… that’s not what James has in view — he’s writing to Christians (brothers and sisters) and the way we’re meant to approach speaking is connected to the ‘righteousness God desires’ and is meant to be about a connection between words and actions. There’s a lot more behind this verse than just a guide to civil conversation, and we’re not actually helping people see the value of the Bible by limiting its impact to ‘wise advice for everyone’… When Jesus talks about the Bible he says stuff like:

“You study the Scriptures diligently because you think that in them you have eternal life. These are the very Scriptures that testify about me…” — John 5:39

It’d be interesting to consider how this shapes how we should speak about same sex marriage, or what our position we should be advocating with great civility.

7. Talk is cheap, but public speech should be costly not free.

As Christians we signed up to the idea that speech should be costly when we signed up to follow the crucified ‘word of God’… Jesus. I don’t think ‘free speech’ in a political sense is dead; words have always had consequences because speakers have always been challenged to back up words with actions (cost), because without that you’re a blowhard or a hypocrite.

The problem with the virtual outrage machine is that clicktivism costs nothing. People are free to jump on to a business’s page and destroy its reputation without ever changing their actions. This is what some now call ‘virtue signalling’ — for talking about virtue to be real not just a signalling exercise, it has to be backed up with action.

Ethical speech should not be free for Christians. It should be costly. Political speech should also be costly (I fleshed this out a bit more in a thing about how to write to your MP). Words for Christians need to be underpinned by action. We’re meant to do what the word says (to quote James). Speech should at least cost us ‘having listened’… but it must cost us more than that. If we want our speech to have integrity we need an ethos that supports our logos.

“Dear children, let us not love with words or speech but with actions and in truth” — 1 John 3:18

8. We should live light in response to this apocalypse (and this doesn’t mean light beer or pulling our punches)

In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it… The true light that gives light to everyone was coming into the world. He was in the world, and though the world was made through him, the world did not recognise him — John 1:4-5, 9-10

The last few days has revealed much about the church, and much about our ability to have meaningful conversations in Australia. It has revealed the gap between what we think and believe about humanity and the world, and what the ‘world’ thinks about humanity. People outside the church have taken offence at a Christian organisation appearing to support a conservative political position because it lines up with Christian moral convictions. They’ve called even talking about traditional Christian views offensive, oppressive, and hateful.

It seems the deck is stacked against us; especially if this is some sort of majority position. If this is the case, we may as well be bold and be offensive for the right reasons, not the wrong ones. If people are going to be offended and mock us whether we make conservative political arguments from natural law, or for approaching the secular political realm as people who believe in the death and resurrection of Jesus (and that this should shape our own politics and how we think of sex and marriage within our own communities, and in terms of God’s design for human flourishing), then why don’t we bring the real light?

“You will be hated by all for my name’s sake. But the one who endures to the end will be saved.” — Matthew 10:22

Jesus says that’s what’s going to happen to us because of his name… and this isn’t some shibboleth test, but I’m not sure the name of Jesus got a mention in this little video. It might just be worth our while to be hated for living light — promoting Jesus in word and deed — rather than being seen to be pushing some sort of conservative political agenda according to the secular rules, or even to be seen to be advocating for the very good thing of public civility (as nice as that would be to see from my perspective as a citizen in the Australian public).

Here’s how this worked for Paul…

Now when I went to Troas to preach the gospel of Christ and found that the Lord had opened a door for me, I still had no peace of mind, because I did not find my brother Titus there. So I said goodbye to them and went on to Macedonia.

But thanks be to God, who always leads us as captives in Christ’s triumphal procession and uses us to spread the aroma of the knowledge of him everywhere. For we are to God the pleasing aroma of Christ among those who are being saved and those who are perishing. To the one we are an aroma that brings death; to the other, an aroma that brings life. And who is equal to such a task? Unlike so many, we do not peddle the word of God for profit. On the contrary, in Christ we speak before God with sincerity, as those sent from God. — 2 Corinthians 2:12-17

If we’re inevitably going to be offensive, let’s be offensive for good reason (and we might just be the aroma of life for some people) rather than carrying the stench of stale light beer.

9. We need less ‘hot takes’ and more cold ones

Hot take (n.)

“a piece of commentary, typically produced quickly in response to a recent event, whose primary purpose is to attract attention.”

Cold one (n.)

“a cold beverage, usually a beer”

I’m reluctant to add this post as another piece of chatter on this issue from the chattering class. Another hot take in a sea of outrage. Another rhetorical ship passing other ships in the night. I’d rather be a lighthouse than a ship.

I’d much rather have a beer with my gay friends and neighbours and really listen to them so that together we might imagine better ways forward than either binary solutions, outrage, or totalitarian solutions that aim to silence those who disagree with us. My shout (let me practice costly speech). It probably won’t be a Coopers this week (I confess, I’ve never drunk a Coopers), and it certainly won’t be a light beer, because I don’t want to mix metaphors, nor do I want to drink light beer.

But this sort of conversation should shed light on life lived together in the world, and on where my hope for my neighbours and our society is really found. The one who didn’t just ‘bring light’ to conversations, but who is the light of the world.

I don’t think civil public discourse is served all that well by fast, attention grabbing responses and conversation by hashtag. I hate boycotts — whether it’s Christians boycotting Halal certified food, or LGBTIQA allies boycotting Coopers. Boycotts are self-serving and self-seeking; they are the worst form of virtue signalling. Imagine how much more effective and persuasive it might be to write to Coopers and say “I don’t like that you’ve done this but I’m going to keep drinking your beer because I value you, it, and your workers”… We Christians don’t change hearts and minds through hostility (even if Coopers has backflipped), but hospitality, love, listening, understanding, and then carefully speaking the Gospel as it relates to an issue.

What saddens me is that as much as this has been a useful revelation about the state of public discourse in Australia, almost all of my Christian friends (myself included) have spent the last three days talking about beer, same sex marriage and civility, when we could’ve been talking about Jesus. Let’s aim our ‘living light’ or ‘keeping it light’ at that goal, even if apocalyptic moments like this one keep revealing that the world can be a pretty dark place.

“Therefore, since through God’s mercy we have this ministry, we do not lose heart. Rather, we have renounced secret and shameful ways; we do not use deception, nor do we distort the word of God. On the contrary, by setting forth the truth plainly we commend ourselves to everyone’s conscience in the sight of God. And even if our gospel is veiled, it is veiled to those who are perishing. The god of this age has blinded the minds of unbelievers, so that they cannot see the light of the gospel that displays the glory of Christ, who is the image of God. For what we preach is not ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord, and ourselves as your servants for Jesus’ sake. For God, who said, “Let light shine out of darkness,” made his light shine in our hearts to give us the light of the knowledge of God’s glory displayed in the face of Christ. — 2 Corinthians 4:1-6