This was part three of a sermon series preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2024. You can listen to this on our podcast, or watch the video.

There is a song you might know — an old nonsense song.

“The grand old Duke of York…”

Sing it in your head.

“He had ten thousand men. He marched them up to the top of the hill, and then he marched them down again. And when they were up, they were up — and when they were down they were down — and when they were only halfway up they were neither up nor down.”

We are thinking about heaven as a mountain top this morning, and I guess we are trying to figure out where we are — are we up, are we down, are we neither up nor down — or are we both up and down at the same time?

How are you going with this concept we are unpacking in this series — the idea that we are not just alive on earth, at the bottom of the mountain, and clearly not just in heaven, on the top of the mountain — but in this overlap — both in heaven and on earth — raised and seated with Jesus so that we are before the throne of God in heaven? It is tricky, is it not? And I wonder if it is trickier for us because we do not have the same relationship with our bodies and with physical space that the people in the Bible had, or the same understanding of heaven and earth as overlapping realities.

See, God’s people in the Old Testament had their own songs — not nonsense ones like the Grand Old Duke of York, but songs they sang every year, every time they climbed a mountain, to teach them how to live in space and time as people who lived with God.

Israel had a physical mountain — the temple mountain of Jerusalem, Zion — where God’s house was on top of the hill as a symbol of his heavenly throne room but also a picture of him dwelling with them. We will look at this structure more over the next couple of weeks. Today we are looking at the mountain itself, and the mountain top as a picture of heaven.

Every time the people of Israel climbed the mountain to go to the temple for feasts and festivals they would sing these songs from the book of Psalms. You will find them in our Bibles with the heading “a psalm of ascent.” They start in Psalm 120 and there are 14 of them. These were songs to be sung on the road, songs to connect the singer’s body to a journey from the bottom of the mountain to the house of God — a sort of ascent from earth to heaven in the imagination of the singer.

The second of these Psalms starts with the singer gazing to the top of the mountain — Zion — looking to the peak, to the temple, and towards the heavenly throne where God, the maker of heaven and earth, sits as helper (Psalm 121:1). The singer is not up yet, but they are on their way.

Some of the songs seem to have come from the other side of exile, after the southern tribes return from Babylon, looking back at how God restored them to the land and restored their fortunes, bringing joy and laughter (Psalm 126:1–2). Just keep that idea in mind and hold it alongside the picture of mountain life in Hebrews 12:18-29, maybe especially:

“But you have come to Mount Zion, to the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem. You have come to thousands upon thousands of angels in joyful assembly, to the church of the firstborn, whose names are written in heaven. You have come to God, the Judge of all, to the spirits of the righteous made perfect, to Jesus the mediator of a new covenant, and to the sprinkled blood that speaks a better word than the blood of Abel.”

These Psalms were songs God’s people sang all the way through to the time of Jesus — they were probably even on the lips of the crowd as Jesus made the journey up the mountain at Passover to be crucified, to truly end the exile, restore Jerusalem, and rebuild a real temple in the place of the one built by Herod about fifty years earlier. People might not have been feeling this joy when Jesus arrived.

But they certainly had this mountain at the heart of their imagination of heaven on earth — the idea that God’s blessing to the world flowed down to Zion, and then down the mountain into the rest of the world (Psalm 128:5). Because Zion — this mountain — was his dwelling place forever and ever, where his throne is (Psalm 132:13–14). This is the picture of heaven on earth in this song book. People sang these songs while climbing the mountain — orienting themselves towards heavenly life and the idea that they were about to enter heavenly space.

Now, we have to be careful here, because this idea of Zion, specifically, the Zion of this world — an earthy mountain in Jerusalem as God’s dwelling place — can lead to all sorts of heaven-on-earth projects that end up looking more like hell on earth, creating death and destruction as we take building heaven on earth into our own hands.

Where the Bible depicts this forever reality, right at the end, being God’s act of renewing creation and removing the curse of sin and death — when the New Jerusalem emerges in Revelation it is heaven being brought to earth, not humans building a bridge between heaven and earth (Revelation 21:2).

The Bible has a story about how that goes wrong right at the beginning — the story of Babel, an attempt to build a stairway to heaven (Genesis 11:4), which, when we looked at Genesis, we saw was a common impulse of nations around Israel.

This looks like a mountain, but it is the ruins of a staircase temple called “the house of the mountain.”

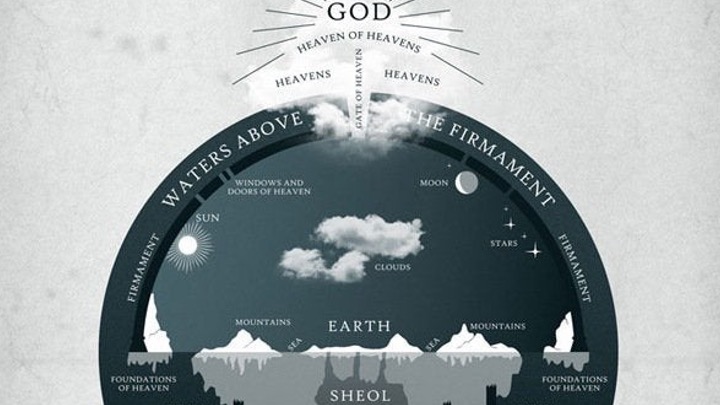

This is the kind of thing you do when your model of reality has heaven in the skies above a dome.

There are dangers when we try to bring heaven down to earth on our terms and for our benefit — not just at a political scale, but in our own lives and what we pursue. But these Psalms and that journey up the mountain to the top — they are capturing something of what we are trying to do this term as we see that we have been raised with Jesus and seated with him at the right hand of God. Part of setting our hearts on things above, and our minds on things above, not earthly things (Colossians 3:1–2), is a bit like the Psalm singers who looked to the mountain in order to look towards God (Psalm 121:1). We are learning what it means to live lives shaped by the top of the mountain, and having been there — and not being halfway up between heaven and earth — but living in this sweet spot as heaven-on-earth people.

And if you caught this in the bit we read from Hebrews, the writer suggests we should understand ourselves as mountain-top people. They say: “We have come to this mountain, the heavenly Jerusalem” (Hebrews 12:22). This is where we are in some real sense. And they draw on more of the Bible’s use of mountains as heaven-on-earth spaces to shape our imaginations.

Saying: “You are not on a mountain that can be touched but that is burning with fire and stormy and scary, where if someone or some animal touched it they would die” (Hebrews 12:18), where Moses was so afraid of God’s presence he trembled with fear (Hebrews 12:21). He is talking about Sinai, and the Exodus story. You are not on that mountain, but on Zion.

He is tapping into a mountain-top story that runs through the Old Testament. If you have read my other ‘sermons as articles’ or tracked with me for a while, you might have heard me talk about mountains before, but maybe not mountain tops — so here is a quick re-cap. See what I did there — re-cap…

I reckon we — or at least I — mostly think of the Bible and its events as though geography does not matter. We are so removed from the physical landscape of these events, but so often the narrator will point us to the environment, or assume we know it, or as the Scriptures unfold will paint more details in for us. So we are not just imagining heaven and trying to picture things this series, but engaging our imaginations to think about life on earth differently too, and maybe to think ourselves into what is called the “cosmic geography” of the first readers of these stories.

So the first mountain in the Bible is — according to Ezekiel — the mountain garden of Eden. The heaven-on-earth garden dwelling of God we looked at last week. Ezekiel describes the location of this garden as “the holy mount of God” (Ezekiel 28:13–14). Trust me when I say there are lots of other mountain moments in the Bible and it can get quite confusing trying to distinguish them all — you can ask me about some of them later.

The big story after Eden, and the escape from Egypt, is the shift from Sinai, in the wilderness, to Zion, in the promised land — the new Eden.

Sinai is where where God descends to meet Israel in the wilderness, and makes the top of the mountain a gateway into heaven (which then becomes the model for the Tabernacle as a ‘mobile mountain top’). The mountain is burning like a smelting furnace because God is going to forge Israel to be his priests, people who bring heaven to earth (Exodus 19). Moses eventually goes up this mountain with some of the leaders of Israel and gets this heavenly vision of God.

Moses and Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and the seventy elders of Israel went up and saw the God of Israel. Under his feet was something like a pavement made of lapis lazuli, as bright blue as the sky.

— Exodus 24:9-10

Take note here, because this account does not describe God, but it does describe this floor under his feet — at the ceiling of the mountain top — this bright blue. That is what lapis lazuli is — this bright blue sparkling pavement. Maybe something to add to the visual bank. At this point these leaders eat and drink, seeing God (Exodus 24:11).

Then Moses goes further, beyond the ceiling, it seems, and into God’s glorious, bright presence — on the top of the mountain (Exodus 24:15–16). To people looking on it looks like he has stepped into the brightness, the smelting fire (Exodus 24:17). And ultimately he comes down glowing, radiating, bringing some of this heavenly glory to earth (Exodus 34:29).

For the writer of Hebrews this is the scary mountain, and it is not our home. They sum up this movement described in the Old Testament from mountain top to mountain top. There are songs about this in the Psalms. Songs like the one that sings to other mountains, this Gentile holy mountain, Mount Bashan, aka Mount Hermon (Psalm 68:15–16). We looked at it in Matthew as the mountain where Jesus is transfigured [note: I didn’t quite get to posting that one as an article, but the podcast is here], and as the mountain where people believed the Nephilim landed in Genesis 6 (at least according to the book of Enoch). Anyway, this other mountain is described as being envious because it is not God’s home. Mountains do things in the Psalms like singing God’s praise. But this one is envious because God is going to choose a different mountain to reign on and dwell forever. He is on the move with his heavenly host from Sinai, in the wilderness, to his sanctuary, his mountain-top home (Psalm 68:17). Which other Psalms explicitly name as Zion, the mountain of Jerusalem, his throne room (Psalm 132:13–14).

The prophets are full of mountains too. Isaiah talks about the end of exile involving a new mountain home for God, on the highest of mountains, where all nations will flock to this place — this heavenly throne. Going up the mountain, ascending to the house of God to learn his ways, the ways of heaven, in order to take those ways down to earth (Isaiah 2:2–3). Isaiah also pictures a mountain, “this mountain,” being the place where God would prepare a feast, and a mountain being where he would destroy the ultimate enemy of all people — the enemy that enters the story when humans leave the first mountain, Eden — destroying death (Isaiah 25:6–8). And he pictures foreigners coming to bind themselves to Yahweh as his priestly people too, and being brought to God’s mountain and given joy in his house of prayer (Isaiah 56:7). Again — remember the joy in the bit of Hebrews we read. This comes from entering this sort of heaven-on-earth reality, temple life, mountain life.

Isaiah says when disaster strikes, people who cry out to dead, breathless gods will be carried off in the wind, blown like breath, while those who take refuge in God will inherit the earth and possess his mountain (Isaiah 57:13), because God — in the prophets — lives on a high and holy place, the mountain, while also dwelling with the lowly (Isaiah 57:15).

This mountain imagery is everywhere in the Old Testament shaping the imaginative world of God’s people as they climbed a literal mountain to meet with God and then sought to live as his heaven-on-earth people.

But like the Grand Old Duke of York’s men, Israel was never sure where they were. They kept living as though they were shaped by earth, worshipping man-made idols in Babel-like temples. They had all the songs in the world, but they did not have God’s Spirit making them heaven-on-earth people.

This is what has changed for the church after Jesus comes as the heaven-on-earth human who also is the human-in-heaven Son of God.

Jesus comes as God’s king fulfilling Psalm 2, as the king installed at his right hand, on Zion, the holy mountain (Psalm 2:6). Jesus climbs that mountain in Jerusalem, perhaps singing these Psalms, to be killed on a mountain, but then raised and seated at God’s right hand (Ephesians 2:6). And as we receive God’s Spirit we are also now people who are raised and seated with him, at God’s right hand — on the mountain top.

We are like Moses, but different. We are now — as Paul puts it in 2 Corinthians — able to be in God’s presence and contemplate his glory (2 Corinthians 3:18); that bright light from a few weeks ago, past the barrier, the blue stones, and in the throne room, being smelted into his image as we encounter this glory, by the Spirit.

This is what the writer of Hebrews is picking up too. We are on the mountain; not Sinai, not even old Zion, but the heavenly mountain-top city that God will bring to earth when he makes all things new (Hebrews 12:22). And as we go up to there, but also live down here, we are being forged to live these heaven-on-earth lives that shine like heaven; not building Babel or trying to reclaim Zion, but living this life of joy and hope, even in suffering, described in Hebrews.

Hebrews gives us some more images to contemplate as we pray and dwell on the mountain top. They invite us to picture thousands and thousands of angels, that heavenly host from the Psalms, in joyful assembly (Hebrews 12:22–23) — a massive gathering. That is what the word “church” means — we have come to this gathering too, the gathering of the firstborn, of Jesus.

We have come to the Father, the judge of all, to gather with all those made perfect — humans, together — to Jesus who brought us into this new covenant, this new arrangement with God by his blood as the mediator, the true priest (Hebrews 12:23–24). And this comes with a new allegiance. We are, if we are going to dwell here, going to be people who listen to the one who speaks from the throne, and not refuse him. If we are heaven dwellers we have this bigger responsibility than those who only heard God on earth and turned away from him (Hebrews 12:25).

Hebrews 12 has some heavy stuff. But look what it says — this voice shook the earth, but now promises to shake the earth and the heavens (Hebrews 12:26). This is a promise to make all things new; it is the same as the vision from Revelation — to bring heaven and earth together into this unshakable forever reality where God will dwell with his people (Hebrews 12:27). We live in this heavenly mountain place hoping and expecting that God will act in this way in the future and give us life in this kingdom that cannot be shaken. And what should we do with this hope? This picture of the future? As mountain-top dwellers already, we should be thankful and worship God with reverence and awe, because the God enthroned in Zion is actually the same smelting God from Sinai. But we come to him as children he loves — united to the Son he loves — to be transformed, not destroyed (Hebrews 12:28–29).

It is keeping our eyes fixed on the top of the mountain — not just “as we ascend” but seeing that we are already secure and home there — that is meant to shape us for life on earth. We are not neither up nor down, we are both. Just before this stuff about mountains the writer of Hebrews opens this section with another image that is meant to shape our life on earth — another heavenly image.

They say: “Since we are surrounded by a cloud of witnesses” — this is not about the angels, it is talking about all the faithful examples of faith and hope in Jesus (Hebrews 12:1); in God’s promises through history listed in Hebrews 11. Since we are captured by this heavenly vision we should throw off the earthly stuff that hinders — things that prevent us seeing reality this way, and the sins that entangle and want to keep us living lives stuck on earth. Lives of sin and destruction and rebellion against God.

Sin is the stuff where our imaginations get captured by worldly things and false gods so we get trapped in the unreality that this world is all there is. Hebrews says throw that off, and do it not just by looking at it and trying to see worldly things differently — do it by fixing our eyes upon Jesus — the one at the top of the mountain, raised and enthroned at God’s right hand — the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, the one who ascended to the top of the mountain not just showing us the way, or carving out the path, not just marching us up to the top of the hill, but carrying us there. We should fix our eyes on him — this, too, is an act of imagining the throne room of God — and we should be shaped by his example. For the joy set before him — his own vision of the top of the mountain, his own vision of God’s unshakable kingdom becoming a reality — he suffered and endured the cross. His vision of heavenly life and God’s faithfulness, this joy being a picture that drove him — he endured the cross and then sat down, enthroned, in heaven at the right hand of God (Hebrews 12:2–4). This vision, and this example of life shaped by it, change how we live on earth.

Keeping our eyes on heaven and the throne together is the Bible’s antidote for smashing into one another and pulling each other down. And it is the antidote, it seems, for sexual immorality — for using human bodies for idolatry (Hebrews 12:16). Thinking other human bodies, or our own, are where we experience heaven — that sex and sensuality are the ultimate goods, or our goal for fulfilment. This is a form of godlessness. It, and other forms of being entangled by worldly things, are a form of the mistake Esau made back in Genesis when he gave up his inheritance, his place in the family, for a single bowl of food to satisfy his hunger. We can get so caught up with visions and fantasies and imaginings of life on earth — good things we want to grab hold of at all costs, things we desire: sex, money, comfort, pleasure, holidays, joy — and miss the joy that comes from eternal hope in Jesus. Not seeing that we are located already on the mountain top, the heavenly mountain top, and longing for the unshakable kingdom to come as God brings heaven and earth together forever.

We are shaped for life in this world — to be those who reflect God’s presence — by spending time in his presence “on top of the mountain.” This is the pattern of the Bible: it is Sinai (Exodus 24). It is the calling for Israel as those who ascend the mountain to meet with God in the temple in their feasts and festivals (Psalm 121). And it is there at the end of Matthew’s Gospel in the Great Commission. The disciples meet with Jesus on a mountain top; they encounter the risen Jesus as he is about to be raised to the heavenly throne. They worship him (Matthew 28:16–17), and they are sent down the mountain to make disciples, those being transformed into his image (Matthew 28:18–20). And it is what the writer of Hebrews is inviting us to do (Hebrews 12).

For us, this series is about imagining what it is like to enter God’s presence as we pray; as we close our eyes to the things of this world and open them to heaven, so that when we are living on earth we are living as people who also dwell in heaven with God, awaiting, longing for, anticipating, modelling, the plans he has for earth. We are thinking about what it means to set our hearts on things above — to lift our eyes to the mountain — and see God.

Last chapter I introduced that idea of meditation on the Bible where we pair propositional ideas with poetic imagery from the text of the Bible. And maybe the writer of Hebrews is actually modelling that. As they place us on the mountain as a picture of heavenly life, seated with Jesus. In doing this we are brought into the imaginative realm of the Psalms; they become our songs. We are invited to sing and meditate on these words, fixing our eyes upon the mountain, singing songs of praise, worshipping God — because he, and the author and perfecter of our faith, are enthroned on this holy mountain, and we are invited to come before his throne.

Psalm 48 is an interesting one to meditate on, calling us to praise the God of this mountain. You can imagine someone in Israel’s peak, in Jerusalem, looking down the mountain to the surrounding country, or at the other peaks in view, singing:

“Beautiful in its loftiness, the joy of the whole earth, is Mount Zion — the city of the King” (Psalm 48:2).

Or while wandering through the temple, singing about meditating on God’s unfailing love (Psalm 48:9).

Or wandering around the walls of the city imagining its strength and security (Psalm 48:12–13), so long as God dwells there. And you can imagine someone singing it in exile, longingly looking back, but also hoping for renewal — a safe and secure home restored with God like he promises.

We too can sing about God shining forth from Zion — a beautiful heaven-on-earth hilltop, with God shining forth — where Zion reflects Sinai (Psalm 50:2–3). We can imagine ourselves on the mountain top with Moses walking through that crystal barrier into God’s throne room. We can sing the Psalms of Ascent, lifting our eyes and hearts to the mountain of heaven, where we are raised and seated with Christ so that we do not get caught up in the things of this earth — as people who do not live halfway up or down, but both up and down, bringing heavenly life to earth.

It is interesting that when Paul talks about setting our minds and hearts on things above he encourages us to let the message of Christ dwell among us richly as we teach and admonish each other through Psalms, and as we sing (Colossians 3:16). Owning and meditating on the Psalms as our songs fulfilled in Jesus, because we now dwell on the mountain with him, waiting for him to make all things new. This is part of living heaven-on-earth life now.

Maybe this week you could climb a mountain and read the Psalms of Ascent, alone or with a few other people, picturing life on the heavenly mountain top, spending some time with God away from the things that hinder or the sins that entangle — fixing your eyes on Jesus, and enjoying the future he has secured for you. We do not actually need to physically climb a mountain, but maybe it would help to engage your body and think differently about the lay of the land. Let’s head to the mountain top in our minds now in prayer.