This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 43 minutes.

Do you want your name to last beyond your time here on Earth? I don’t know my grandfather’s father’s name on either side of my family. Do you?

It’s unlikely any of us will be remembered in a hundred years. And I’m increasingly okay with that—I guess because I realize that there are people whose names we remember because they did outrageously awful things, like Judas, Hitler, Nimrod, or John Dring, who invented the first instant coffee in 1771.

We can try to make a name for ourselves—but others have sought to make a name for their city or nation.

Building projects—making giant stuff—is one way to put a place ‘on the map,’ like Coffs Harbour with its Big Banana, Nambour with its Big Pineapple, or the Gold Coast with its Big Clive. If anybody has tried to make a name for themselves in Australia this year—Nimrod style—it’s the guy who has put up billboards and images of himself everywhere.

This isn’t just an Aussie thing—we do like our big things—but in Brazil, there’s a town trying to make a name for itself using the name and image of Jesus.

Obviously, Rio de Janeiro has had its Christ the Redeemer statue for ages; this town, Encantado, has built a taller Jesus statue—five meters taller—Christ the Protector.

I just love this image from construction time.

But now, you can take photos from his heart.

How lovely.

Just what Jesus and the first commandment wanted us to do.

You can book your holidays now—and while you’re there—maybe you could book a trip to the Creation Museum in America— built by Aussie Ken Ham— where work is beginning on a Tower of Babel; a life-size replica.

Human projects are so often part of us attempting heaven on Earth projects in our name, not God’s. And look, neither the Jesus statues nor the replica Tower of Babel are only built to make a person or town’s name famous, but they feel like other big things. Tourist attractions rather than architecture representing heaven on Earth like—say—the Temple in the Old Testament.

I can’t help thinking the builders of these projects haven’t quite nailed the way the Bible approaches monumental building projects—whether they’re bricks and mortar, or ways to promote His name.

So the Babel story has some background. One way to read it is as a prequel to the events we read last week because here the whole world’s got one language (Genesis 11:1). In chapter 10, in the table of nations, the text says these nations spread across the world each with their own languages (Genesis 10:5). It’s also more of the Bible’s origin story of Babel — Babylon— which we were told Nimrod built last week (Genesis 10:10). The passage starts on the plain of Shinar (Genesis 11:2-3), a word that’s also translated as “Babylonia” in the Old Testament, like in Daniel (Daniel 1:3). We’ll see that this story relates to other origin stories, and especially the Enuma Elish, the story of the creation of the city of Babylon and its temple tower as a gateway between the heavens and the earth.

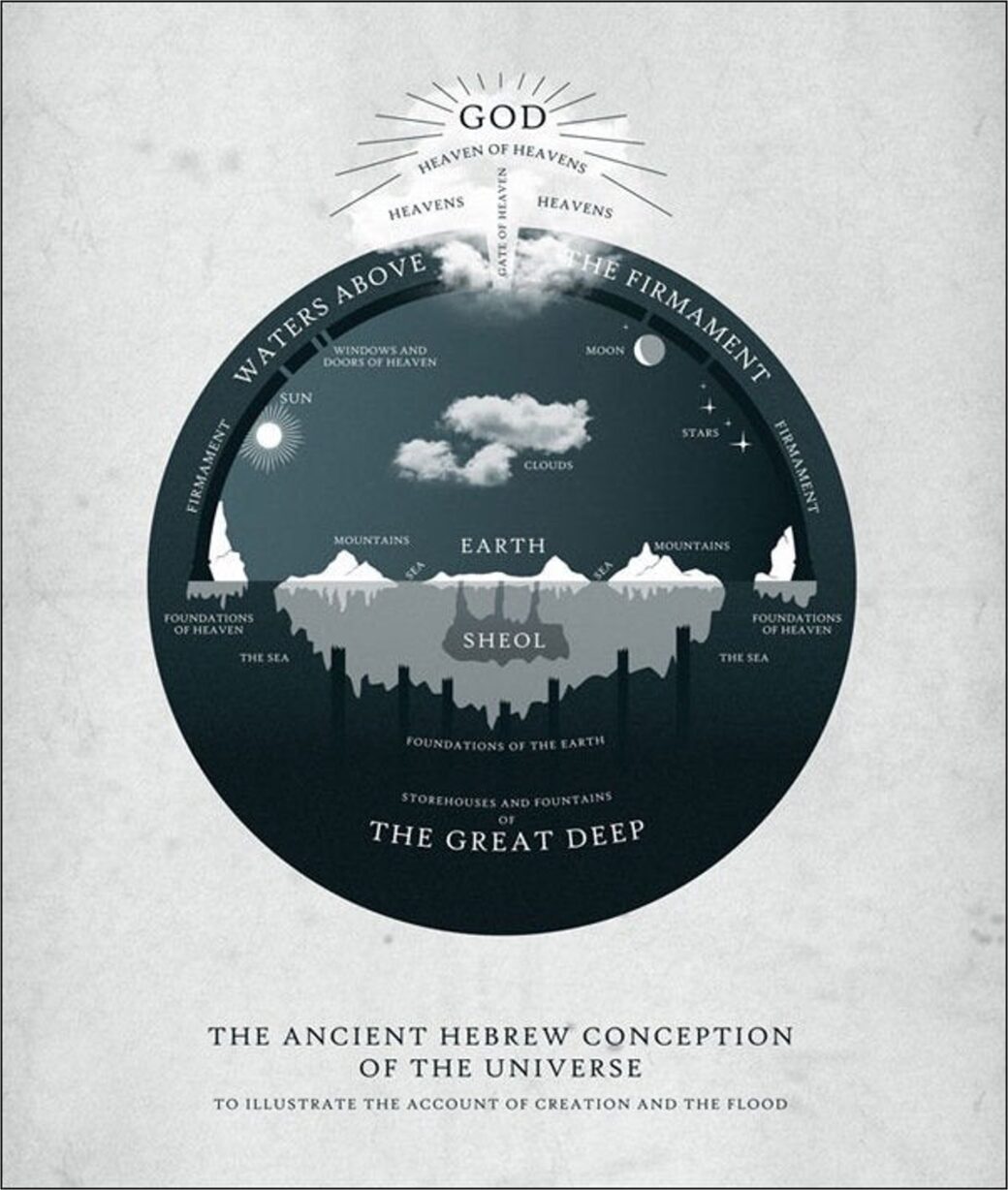

There’s also some Genesis backstory that I reckon should inform the way we see this. Let’s remember that in the beginning, God created the heavens and the Earth (Genesis 1:1), and that for the first readers of this text, their concept of reality was that heaven is high above the earth—through the dome. God created humans to represent Him on Earth like God rules—with the ‘us’ He speaks to in Genesis 1—in the heavens (Genesis 1:26-28, Psalm 8:5-6).

We’ve seen how there are other heavenly beings who are part of a divine council — heavenly rulers — in the Bible’s story, and how some of these sons of God tried to bring heaven to Earth on their own terms in the whole Nephilim episode; they try to bring heaven down (Genesis 6:4). I mentioned then that Babel is a mirror of that story with humans trying to bring heaven and Earth together from the ground, even from bricks made from the ground (Genesis 11:4).

There’s just a couple of other things to bear in mind here too — we open with this final move eastward (Genesis 11:2). This is as far east of Eden as we get in the story of Genesis; that movement that began with humanity’s exile from the garden ends here in Babylon (Genesis 3:24, 4:16), and the construction of a city (Genesis 11:4). So far cities have been bad places in Genesis; human versions of the garden, but without God. The only other use of the word city that’s used here is for the city Cain built, that became the city of his violent descendant Lamech (Genesis 4:17). The word used for city means fortified or guarded place. What’s interesting here is that the word for garden that we get in Genesis is literally an enclosed place (Genesis 2:8).

We’ve got these two sorts of places that are marked out as ‘not the wilderness’ — and I reckon they unfold in contrasting ways; one type of non-desolate land is made by God, with boundaries He establishes, while the other’s made by humans who’re trying to recreate heavenly life outside Eden — with the walls we put up, and trying to shove heavenly life in on our terms.

Walls were an interesting part of nation building — the capacity to shift life in the ancient world from nomadic to something like urban life. You can read a bunch about them in this book Walls: A History of Civilisation in Blood and Brick.

Walls separated the desolate and uninhabited land in the ancient world — where nomadic warrior people and shepherds would roam, fighting off predators, plundering the weak — from the cultured city space where people lived in comfort and security, protected from the wilderness, where they would carry their goods — and bricks — in baskets. Here’s a quote:

“The world outside their walls was not exactly uninhabited, but it was, in the eyes of the basket carriers, dangerous. This was civilization in its infancy: every city its own frontier, never far from hostile neighbors in the mountains, desert, or steppe.”

People living behind walls found comfort, security, and wealth, so kings through the ancient world would brag about their wall building as the source of their power.

Chapter 1 of Walls explores exactly this period in history — life before Babel. Before baked bricks. Before bricks walls were just mud, and they’d sink, and you couldn’t defend them. Baked bricks, like we find in Babel, brought a whole new era of building stuff to make a name for yourself, and to build with ambition; a whole new way to make new Edens, or cities. Here’s another quote:

“Lacking sufficient fuel to bake all their mud bricks, the Mesopotamians settled for drying them in the sun, a process that created building blocks of such dubious quality that they could not withstand even occasional rain.”

So we zero in on the origin story for this city — Babel — Babylon — the story of Nimrod the warrior king from chapter 10 getting people together to build a city trying to bring heaven on Earth, to make a name for himself like he’s a Nephilim; so he’s not just a mighty warrior, but a man of name. They’re on a plain — not a mountain — and he’s using this new brick technology (Genesis 10:10).

Genesis is retelling the story of the god-king Gilgamesh — whose epic is an origin story shaping the life of other nations in Mesopotamia. On the very first tablet of the Gilgamesh Epic, one of the very first boasts is that he built the wall and the temple of the city of Uruk — which Genesis 10:10 said was one of the cities Nimrod built.

Here are some quotes from the Gilgamesh Epic:

“He carved on a stone stela all of his toils, and built the wall of Uruk-Haven, the wall of the sacred Eanna Temple, the holy sanctuary. Look at its wall which gleams like copper…

Go up on the wall of Uruk and walk around, examine its foundation, inspect its brickwork thoroughly. Is not even the core of the brick structure made of kiln-fired brick…

One league city, one league palm gardens, one league lowlands, the open area of the Ishtar Temple, three leagues and the open area of Uruk the wall encloses.”

Nimrod, in the Israelite imagination, is Gilgamesh.

The Epic says these walls were made from kiln-fired bricks, and the walls encompassed this whole open area — the temple, the city, and the plains. Where that epic tells the story of Uruk, Genesis zeroes in on the Nimrod-Gilgamesh character building Babylon. We’re going to meet a later Babylonian brickman in a bit — but for now the camera’s pointed on Nimrod and his quest moving from a forgettable nomad to a builder of cities — from being a warrior on the Earth, to a warrior king directing earthworks — building walls and filling the space behind them.

Look what the goal is here as they build a city and then a tower to reach the heavens from the Earth; literally it’s a tower with its head in the heavens (Genesis 11:4). It’s the same word for the top of the mountains in the flood (Genesis 8:5). They want to make a name for themselves and not be scattered — only, we’ve just seen the nations scattered already; so we know how that’s going to go, and we know that humans were meant to fill the Earth — spreading — spreading a garden meeting place between heaven and earth made by God rather than a city made by humans (Genesis 1:28, 11:4). Remember too, somewhere in the Israelite imagination, at least according to Ezekiel, Eden was a mountain (Ezekiel 28:13-14). In Genesis 3, Eden was a meeting place between heaven and Earth, where God walked — and — that’s exactly what Nimrod and his buddies are trying to build (Genesis 3:8).

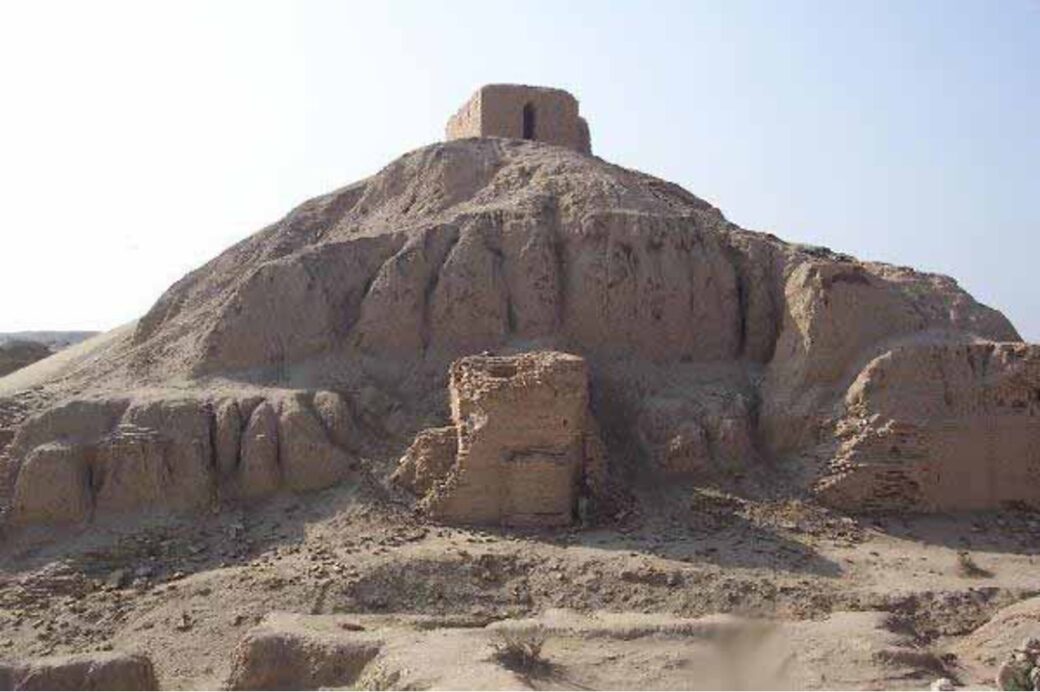

This tower to the heavens is what is called a ziggurat — a type of temple from the ancient world. It’s more than a temple, it’s a gateway between heaven and Earth. A set of steps that the gods could climb down, so Nimrod the Brickman builds one of these Ziggurats.

We have names recorded for ziggurats from nations around the same time — that are all variations on the theme ‘Mountain House’ — these buildings — like this one in Ashur that was called “the house of the mountain” — this was man-made, and its ruins look like a mountain.

Or there’s this one in Nippur called “the house of the mountain of heaven and earth” — these were man-made mountains with their heads in the heavens.

The Mesopotamian region had their own walled-garden-mountain-temple idea — their own Eden, and that’s what is being built here; a gateway, in a city, to bring divine beings — God, or sons of God — down to earth. It’s a staircase to make the events of Genesis 6 happen again — bringing heavenly life to earthly people to make their name. It’s a monumental project.

In Babylon’s own creation story the Enuma Elish, there’s a tower just like this. Only in that story the tower is built by the gods so they can come down. In this story, Marduk, the chief god, tells humans to build Babylon by making bricks. Here are some quotes:

“Build Babylon, the task you have sought. Let bricks for it be moulded, and raise the shrine!” The Anunnaki wielded the pick. For one year they made the needed bricks.

They raised the peak of Esagil, a replica of the Apsû. They built the lofty temple tower of the Apsû.”

Then:

“Be-l seated the gods, his fathers, at the banquet. In the lofty shrine which they had built for his dwelling, Saying, “This is Babylon, your fixed dwelling, Take your pleasure here! Sit down in joy!”

When they “raise the peak of Esagil,” that’s a word that translates as “the house that raises its head,” it’s a replica of the Apsû — which are those flowing living waters in the Babylonian story. A mountain where the waters of life flow out (that sounds like Eden). They build a lofty temple tower. So the gods come down and party with them in Babylon — their “fixed dwelling,” this lofty tower.

The Babel story turns this on its head.

The Gilgamesh-Nimrod king who wants to be a Nephilim — who wants to make a name for himself — he’s not a grand heavenly player who is godlike; he’s a wannabe. He has this grand unity plan to make himself a god on earth, but things don’t go the way he wants. There’s no divine party. Before they even finish the tower that is meant to bring heaven to earth, God comes down (Genesis 11:5).

He takes one look at this tower project — and there’s an echo of Genesis 3 here — where there he says “they’ll be like one of us” — when they already were, he says if they finish this “nothing they plan will be impossible” (Genesis 11:6). This is another push to be godlike — heavenly humans on earth, but they’re doing it wrong.

They’re trying to build a Garden of Eden — a place where God dwells on earth with His people — rather than receiving that as a gift from God. It’s an attempt to build security and paradise and a name on earthly terms, with baked earth, rather than letting God make His name great through His earthly representatives — images of His heavenly rule — given life by His breath.

So God — just like he does in Genesis chapter 1 — says “Let us” (Genesis 1:26, 11:7). There’s a plural here that could be God talking within the Trinity, or it could be God talking to the divine council — and there’s a reason to think that’s what’s in view here that we’ll see in a minute. Then rather than the humans coming up into heaven, or building a tower that enables God to come down — God comes down to confuse — which is the same word for Babel or Babylon in Hebrew — He Babylons the people, scattering them all over the world, and the city doesn’t even get finished — this heaven on Earth project doesn’t work out; even if Babylon is going to look great, and bricky, and powerful with its garden mountains and lofty temples and big walls — it isn’t Eden. It offers no security.

And this scattering—into nation states around the earth—it’s an act of judgment on these nations (Genesis 11:8-9). We’ve picked up Deuteronomy 32 a couple of times in this series—back when we were talking about the sons of God, where we noticed that there’s a good reason to translate this verse as God setting up the boundaries of the nations according to the numbers not of the sons of Israel, who haven’t been born yet when the nations are scattered in Genesis 10 and 11, but according to the sons of God (Deuteronomy 32:8-9). This act of scattering in Genesis is him disinheriting the nations—giving them to the sons of God, these other heavenly beings in the divine council to be ruled by these powers and principalities—while God keeps his own people, Israel, as his portion—his own inheritance.

There’s a warning here about what’ll happen if God’s upright people—Jeshurun means upright—abandon the God who made them—fathered them—and who saves them—to bow down to these gods—idols, and literally here in bold demons—a word only used twice in the Old Testament—but the nations aren’t condemned for this idolatry here (Deuteronomy 32:15-17). Just Israel, who’re God’s children. The punishment for this people; it’s to be scattered and to have their name erased (Deuteronomy 32:26). It’s exactly what the people in Babel wanted to avoid; and what happens to everyone at Babel.

Reading Deuteronomy this way—picking up a thread from Babel—I reckon, is compelling when you look at how Genesis moves from the people who want to make a name to the line of the son of Noah whose name is Name, the line that now runs all the way to Abram, whose name God is going to make great as he blesses the nations (Genesis 12:1-3). We’ll see more of Abram’s story next week—and there’s another good reason to read Deuteronomy 32, and its commentary on God’s relationship to the nations and to Israel this way that comes a little earlier in Deuteronomy, in chapter 4, where God says all the other nations have been given over to the worship of these other heavenly bodies—the host of heaven, while Israel has been brought out of the furnace of Egypt—like a cast idol statue—a baked people—as God’s inheritance (Deuteronomy 4:19-20). It’s similar to the language Exodus uses when it talks about Israel as a kingdom of priests (Exodus 19:5-6).

God’s people are called out of the scattering that happens when Nimrod builds this temple city of Babylon to make a name for himself; this walled centre of security trying to bring heaven and earth together on human terms. Cities can be like this — centres of human security without God appearing to set the boundaries, which is part of the story for Israel through its history as it comes to have its own cities, and its own walls, and its own heaven on earth spaces—the tabernacle, while they’re living as people without walls; people roaming the earth heading towards a destination—the promised land.

On their journey, we’re often told about the cities in the land as though they’re little Babylons—walled cities full of violent people—led by giant kings—that was what scared the spies who were sent into the promised land (Numbers 13:28). On their journey, we’re told about these big cities, with big walls and giant people—like King Og, or the Anakites, as though these walls offer security against God’s plans (Deuteronomy 3:3-5, 9:1-2), but like Jericho with its famous wall tumbling story—these walls weren’t a barrier to God.

Israel is warned that when they turn to idolatry and get scattered—these same walls, in their cities, won’t protect them either. He’ll bring a nation against them from far away. A nation whose language they won’t understand, who’ll tear down their city walls, and cart them off. They’ll be scattered just like the people in Babel—only they’ll be scattered into Babel itself (Deuteronomy 28:50-52, 64). The seeds for the exile are planted in the Babel story, and in the way the Old Testament picks up these threads.

So this becomes a particularly interesting story for Israel while they’re in exile in Babylon. Nimrod isn’t the only Gilgamesh figure in the Bible. He’s not the only brickman. What he does with his cities and the Babel story in Genesis, king Nebuchadnezzar repeats—and Daniel wants us to see the repeat of the name-making warrior king—a Nimrod—who wants his own version of heaven on Earth; his own Eden.

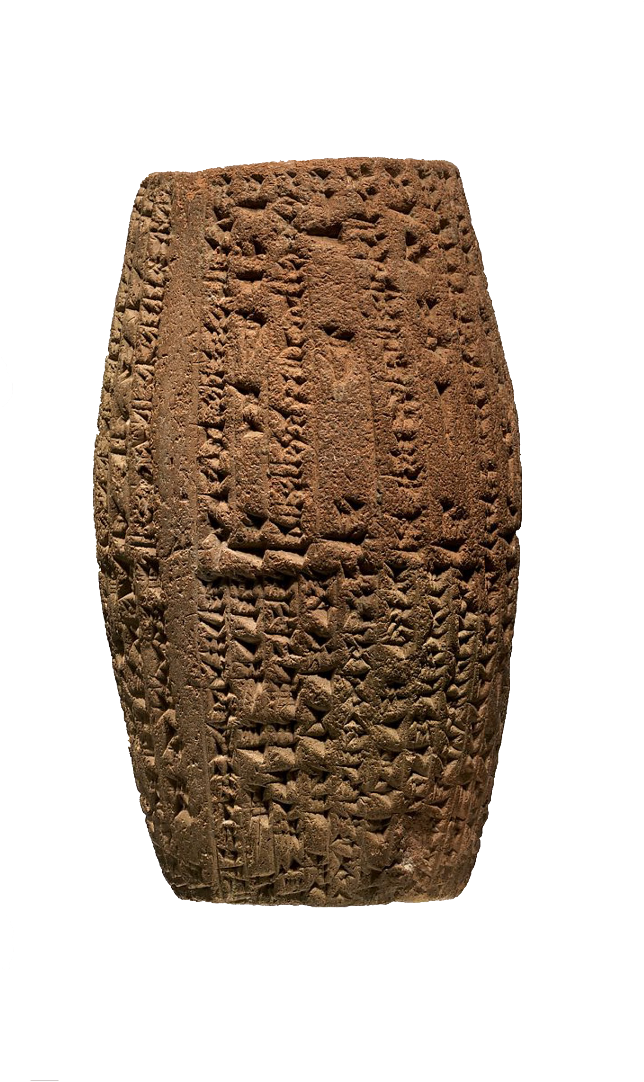

Babylon’s king Nebuchadnezzar was a mighty warrior king in history who expanded Babylon’s empire—including by taking the southern kingdom of Judah into exile—he might’ve inspired just how popular the Gilgamesh Epic became by being a city-building god-king. He was a famous brickman. Like Nimrod who built with baked bricks and tar, he built walls (Genesis 11:3).

There are stacks of surviving inscriptions like this one about his building projects; where he brags about the strong wall he made with bitumen and baked bricks, building this as high as a mountain. Just like in Gilgamesh. Just like in Babel.

Here’s a translation from some of the inscriptions:

“I built a strong wall that cannot be shaken with bitumen and baked bricks… I laid its foundation on the breast of the netherworld, and I built its top as high as a mountain.

I added to the palace and raised it as high as a mountain with bitumen and baked brick.

I constructed a strong, sixty-cubit spur of land along the Euphrates River and thereby created dry land. With bitumen and baked brick, I secured its foundation on the surface of the netherworld, at the level of the water table, and raised its superstructure.

As for the merciless, evil-doer… I drove away his arrows by reinforcing the wall of Babylon like a mountain. I strengthened the protection of Esagil and established the city of Babylon as a fortress.”

Nebuchadnezzar the Nimrod brags over and over about building brick mountains. Even that he made dry ground on the waters—like Genesis, but also like the tower in Babylon’s creation story—and in Babel—out of bitumen and baked brick. He brags about driving back Babylon’s enemies and protecting the ‘house that rises its head’—establishing Babylon as a fortress.

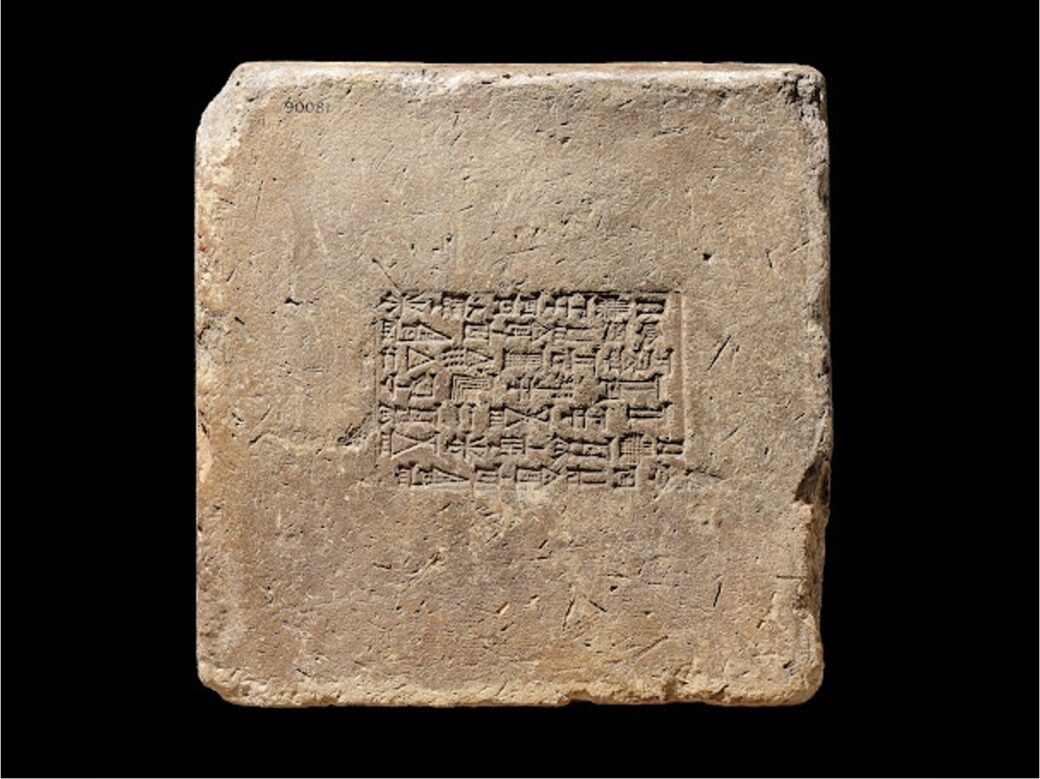

And every brick laid was Nebuchadnezzar making a name for himself—it’s estimated there were 15 million bricks used in his construction projects—bricks like this one.

Each one was imprinted with his name and a list of his achievements as a temple builder who made tower-mountains that reached the heavens. These braggy inscriptions were on every brick, on every wall, and built into the foundation of every project.

You want to make a name for yourself in Babylon, you be a brick-man. A Nimrod. A Nebuchadnezzar.

Daniel draws a link between Nebuchadnezzar and the Babel story.

He starts off with Israel being brought to the plain of Shinar, and then, over time, has Nebuchadnezzar getting too big for his boots in a ‘head in the heavens’ scene. This time it’s not with bricks but with gold. Nebuchadnezzar, like Nimrod, goes to the plains of Babylon and he builds a giant tower with its head in the heavens (Genesis 11:2-4, Daniel 3:1), only this tower isn’t a ziggurat, it’s a giant image — it uses the same word as Genesis 1 just in Aramaic — it’s a giant golden image of God, representing his rule.

He does this right after Daniel interprets a dream where Nebuchadnezzar’s kingdom was a gold bit of a statue made from different materials; it’s just the head (Daniel 2:38-39). He wakes up and builds the entire ‘man’ of his dreams from gold. He’s claiming his kingdom and name will last forever; that he’s the one who’ll bring heaven and earth together as he unites all people under his rule; people of every language bowing and worshipping on his command (Daniel 3:4-5). What a Nimrod.

Just imagine for a moment reading the Babel story while you’re in Babylon. That’s where the big story of Israel’s history — Genesis to 2 Kings — ends up. Imagine reading about Nimrod while carting around bricks with Nebuchadnezzar’s name on them, building his towers. The book of Daniel is a kind of ‘after the event’ commentary on faithful life in this moment in history, but the Genesis story invites you to see Babylon and its mountainous buildings that are trying to link Babylon to the gods, and its Gilgamesh-like king who is uniting the earth while trying to make his name great with these building projects as a dead end. As a path to disinheritance and being scattered, and being brought down. Nebuchadnezzar is a Nimrod; and so is anyone who tries to unite heaven and earth without God.

But God has a heaven and earth reunion project he’s working on through history (Daniel 2:44), one that centers on a king who brings heaven to earth in a forever kingdom as he lives not for his own name, but for God’s — a son of Abraham — who brings blessing and restoration to all nations.

Another inversion of the Babel story comes with the nations, not just Israel, being not disinherited but re-adopted. That’s the story Paul tells when he visits Athens; a modern-to-his-day Babylon, with amazing walls and lots and lots of idol images (Acts 17:26, 30-31). He looks at these images as attempts to reach heaven, and how God’s plan was to bring all people back to himself, even after they’re given the boundaries of their lands, Deuteronomy 32 style; given over to the powers and principalities and this temple building idolatry. He says something has shifted in the heavens and the earth, where the God who “isn’t served by human hands building stuff out of bricks” has revealed himself through this one man; Jesus, who is now the ruler of the heavens and the earth — and all nations. Jesus the anti-Nimrod, who calls us out of our own building projects and into his.

Those are two threads tied up, but what about the bricks and the temple building? Our “brickman” tendencies to get swept up in the name-building project of our empires? Or even our own name-building, image-making efforts; whether that’s to make a name for ourselves now, in our own spaces, or to be like a Nimrod or a Nebuchadnezzar or a Big Clive, or a Donald, trying to build a kingdom that will last.

Here’s a fun payoff for that thread. Babel was a temple-building project, trying to bring heaven and earth together, which is ultimately God’s plan for the renewal of the heavens and the earth. At the end of the Bible’s story we see the heavenly city descend so humans live with God, and have his name written on us (Revelation 21:1-2, 22:4). There’s a rabbit hole here where the Hebrew word for “brick” is basically “white stone,” and the faithful church gets a white stone with a new name written on it, as we’re called out of Babylon in Revelation (Revelation 2:17).

But we’re not called to be brickmen — Nimrods, Nebuchadnezzars, or Clives — we’re called to be a brick… Man.

We’re not people who use bricks to make a name for ourselves, but bricks swept up and joined together in God’s building project — connected to the living stone — Jesus. Jesus, God’s living image who reveals what life lived for God’s name looks like; the true Israel and the forever king, who calls us to join in his Exodus-styled kingdom of priests—his living temple—as we journey towards this heavenly home (1 Peter 2:4-5).

The idea isn’t to build monuments or monumental lives so our names’ll be remembered like Nebuchadnezzars—but for our lives to be temple-like monuments to him; as we become a living temple, together, proclaiming the name of Jesus because we know that God remembers our names and we are heirs with Jesus who live lives with this as our story. Nebuchadnezzar might’ve built Babylon with 15 million bricks with his name on them; God is building a heavenly temple with billions of living bricks, through history, with his name written on us.

We’re not brick builders trying to bridge heaven and earth on our own terms, but bricks with God’s name stamped on us, showing the world what God’s bridge between heaven on earth looks like as we get swept up in his program to proclaim the name of Jesus. Being part of this building project is the anti-Babel way to invite people to meet the anti-Nimrod king who brings the nations back into relationship with God through his death, resurrection, and the pouring out of God’s Spirit to give us heavenly life here on earth.