In the last few weeks I took my 4th, 5th and 6th trips with Uber. This got me thinking some more about work, and about what it looks like for Christians to be disruptive in what some are describing as a ‘disruptive age’…

I think that’s one of our tasks as Christians; to disrupt the status quo in our world; to challenge human institutions set up around the insidious idols of greed and power, and the way these idols consume those at the margins of our society. This disruption of idols is part of proclaiming (and living in) a different sort of kingdom, in service of a different sort of king.

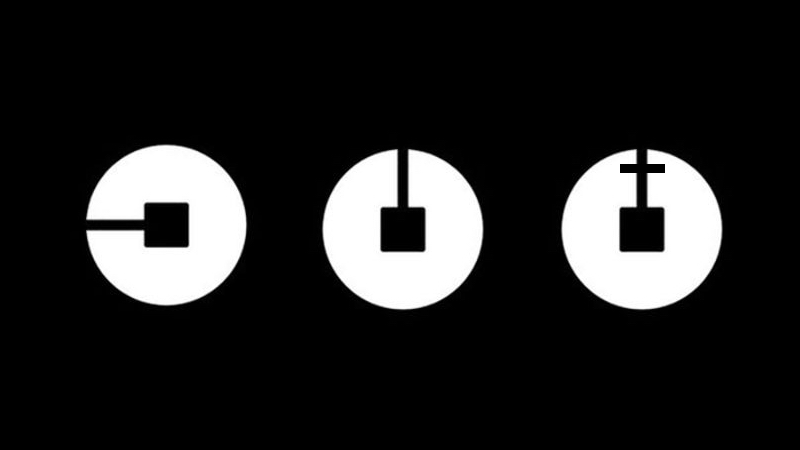

There’s been a lot of talk about Uber as a disruptor; a company that has harnessed new technology to disrupt an existing market (the taxi market). Just how disruptive Uber is; and how much it’s just a more efficient iteration of the existing industry is a bit up for grabs. But thinking about disruption in the context of my Uber trips and time at Hope St Cafe got me thinking that the Gospel should make Christians disruptive when it comes to work and how we think about the economy and our relationship to it. Here’s a neat little definition of disruption from Professor Kai Riemer from the University of Sydney.

“Disruption is actually a fundamental change in the way we view and use products and what we understand and take for granted about an industry, not just an improvement brought about by a new product or player.”

Here’s a little example of how the Gospel disrupts idolatry in the sphere of work and the economy in the town of Ephesus.

“A silversmith named Demetrius, who made silver shrines of Artemis, brought in a lot of business for the craftsmen there. He called them together, along with the workers in related trades, and said: “You know, my friends, that we receive a good income from this business. And you see and hear how this fellow Paul has convinced and led astray large numbers of people here in Ephesus and in practically the whole province of Asia. He says that gods made by human hands are no gods at all. There is danger not only that our trade will lose its good name, but also that the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be discredited; and the goddess herself, who is worshiped throughout the province of Asia and the world, will be robbed of her divine majesty.” — Acts 19:24-27

This is a disruption story.

The city riots. It riots because the Gospel challenges the economic status quo which is tied very closely to the idolatrous status quo. As humans, how we work — and view work within a culture — is always, fundamentally, a question of who, or what, we worship. The Gospel prompts more than simply an incremental improvement in the way we approach the economic status quo… it provides a whole new framework for how we think about the economy and about our humanity; we’re not just economic units (homo economicus), but worshippers (homo liturgicus) who shape the world as we are shaped by our gods.

To be a Christian is to be disrupted, and to become a disruptor... because we’re actually not pushing people out of false worship, and into truth, if we don’t change the way they think about work and bigger stuff like the economy, what it means to be human, and how we live in the world (and what our way of life costs others).

It’s not just that we no longer worship like we used to when we become Christians; this means we no longer work like we used to (or understand work like we used to).

The cross of Jesus changes our approach to life, and status, and people; and the story of the Bible, which begins with a God who creates (who works) and then rests, who creates us to create (to work), and rest, puts a particular value on work and sees it connected to who we are, who God is, and how we relate to God as image bearers who reflect who he is. Becoming a Christian doesn’t make work less valuable (though that has sometimes been a Christian misfire when we’ve devalued ‘secular work’ to make ‘sacred work’ (preaching the Gospel) the be all and end all); it makes work more valuable because it connects it to something bigger than our own little human kingdom; or to ‘human kingdoms’ (like corporate empires, or companies, or national economies), it connects it to the kingdom of God.

The age of disruption means what our society thinks of work, and how we approach work, is up for grabs. It is being redefined and that presents an opportunity for us, as Christians, to re-think the way we approach work amongst our neighbours. We haven’t been great at being different to our neighbours when it comes to work, lots of Aussies tacitly embrace what has been called ‘the protestant work ethic’ built on hard work, discipline and frugality, but more protestants embrace what I’d call the ‘western work ethic’ where we work to fuel our consumption, and to bring some sense of meaning and purpose to our lives. We work like Demetrius in Ephesus worked, and just like our neighbours work… when we could be working quite differently.

We should be theologically geared, or tooled, to think differently about work, because we think differently about our humanity and about God; and that difference should mean we’re able to challenge visions of work that express a different view of humanity and God.

The end of work?

In the last year I’ve heard a couple of Aussie Christian thinkers talking about the future of work for Christians, and for Aussies in general — one suggested that the future for Christians in industries like law and medicine will become fraught because of changing social views on sexuality, gender, and other things that’ll push Christians to the economic/employment margins, another was talking about entering the fray on weekend penalty rates because of the importance of protecting our ability to rest; a lesson in part taught by the Biblical concept of the Sabbath. His prediction is that work is going to creep into more and more time in the average week.

I didn’t get the impression that either of these thinkers (and they’re both pretty smart) were grappling with how technology might disrupt the status quo and change the nature of work; they both seemed to be talking about the future of work as we know it undisrupted work, the future of work as defined by companies whose interest is in sustaining current companies and incrementally improving current practices. I’d suggest both of them are inclined to be conservative in their outlook (politically, and socially) so more likely to be concerned about our ability, as Christians, to participate in traditional social institutions, and more likely to think in terms of incumbent economic institutions and concerns than disruptive ones. This video from the Harvard Business Review explains a bit of the dynamic between ‘incumbents’ and ‘disruptors’…

The Uber-men

I like to talk to my Uber drivers. Last week I met Thiago, he’s a Brazilian university student; he’s got a background in Industrial Design, but he’s over here studying marketing. He’s also a Christian, and we talked about church, and Jesus. His Uber driving allows him the flexibility to study, to be involved in church, and to be in a financial position, in his sharehouse, to be generous and hospitable to people. We talked about some products he had ideas for; that he wants to develop and launch, and spoke a bit about Kickstarter, and the potential for designers to raise capital for projects via crowd funding.

Then, I met Roman, he’s from Afghanistan, via New Zealand, and he’s a dad with three kids; like me. Driving for Uber gives him the flexibility to be home at dinner time, to be there for his kids; like me he’s concerned about the way our culture’s environment and approach to work and life will shape our kids. He works hard so that their mum can stay home for these vital years, but he’s glad he doesn’t have to miss time that they’re awake. The flexibility of this type of work is important to him.

Work as we know it is changing; and there’s a couple of competing views of the trajectory we’re on; both to do with technology. New technologies have always changed the way we work; that’s the heart of what technology is; in one sense technology is about the tools we use to shape our world. In one view, technology will ultimately replace work altogether, we’re heading towards a ‘post-work future’ where everything is automated. Here’s a quote from a long-form piece in The Atlantic a couple of years ago, A World Without Work.

“When they peer deeply into labor-market data, they see troubling signs, masked for now by a cyclical recovery. And when they look up from their spreadsheets, they see automation high and low—robots in the operating room and behind the fast-food counter. They imagine self-driving cars snaking through the streets and Amazon drones dotting the sky, replacing millions of drivers, warehouse stockers, and retail workers. They observe that the capabilities of machines—already formidable—continue to expand exponentially, while our own remain the same. And they wonder: Is any job truly safe?”

In an alternative, still technology driven view, technologies will continue to ‘disrupt’ traditional patterns of work in much the same way that Uber is disrupting the transport industry (and providing new opportunities for work for lots of people); this new opt-in, flexible, type of work has been described as the ‘gig-economy’… here’s a quote from McCrindle research anticipating that this will shape the workforce of the future in Australia:

Firstly, they will live longer than previous generations, work a lot later as well – into their late 60’s, they will move jobs more frequently, staying about 3 years per job, which means they will have 17 separate jobs in their life time and work in an estimated 5 careers. They will be a generation of lifelong learners having to plug back into education to upskill and retrain throughout their lives. In this era of online services like Uber, Airtasker and delivery services, we have seen the rise of the “gig-economy” and more of this generation will end up being freelancers, contractors or contingent workers than ever before. Recent research shows that a third of the national workforce currently participates in contingent work, and more than 3 in 4 employers believe that it will be the norm for people to pick up extra work through job related websites or apps.

These are two very different visions of work, underpinned by technology — the ‘post-work’ future where almost nobody works but we enjoy machine driven prosperity (and work is largely in the creative/design space of technological innovation, or in the arts, including the ‘technological arts’), and the ‘gig-economy’ where we harness technology to be able to work on our own terms according to our own schedules and desires (which does have the potential to lead to very terrible ‘work-life’ balance, even more than the death of penalty rates on weekends). Both these visions remove some power and prestige from ‘status quo’ careers that occupy the centre of our society.

If the guy I heard speak about the future of work for Christians in Australia is right; if we’re facing a sort of pressure that will squeeze us out of roles at the centre of the social order (and of a particular sort of influence) and out to the margins, then the gig-economy offers a sort of refuge for us. He was relatively pessimistic about the impact of these changes; suggesting that for the first time, Christian parents in our country face the possibility that our children will not be as comfortable as we are; that they’ll be worse off. Which for many parents will be a sort of rude shock, and a thing that every part of our natural inclinations will rage against. It’s a very possible vision of the future. And this guy wasn’t offering analysis beyond the descriptive/predictive about whether or not this is actually a good thing for Christians… I think he’d also acknowledge that there are many ways that ‘less comfortable’ is both a good and necessary thing, and that there might be some good outcomes for Christians operating as a subversive community at the margins. I want to be hopefully optimistic, not just because such a position will remove us Christians from some of the gravitational pull of some big idols in our culture — power and wealth — and allow us to speak more clearly about, and less affected by, those idols, but also because real disruption comes from the margins. What marginalisation represents is an opportunity to properly innovate apart from the status quo; and the status quo is actually toxic; we’re no better than Ephesus in Paul’s day; and the Gospel should threaten the profits of those who profit from peddling destructive idols now, just as it did then. It can’t if we’re complicit in the systems that sustain those idols… and let’s not kid ourselves; the way we approach work is fundamentally defined by the gods (or God) we worship, here’s a little more from that Atlantic article, bolded for emphasis.

“Futurists and science-fiction writers have at times looked forward to machines’ workplace takeover with a kind of giddy excitement, imagining the banishment of drudgery and its replacement by expansive leisure and almost limitless personal freedom. And make no mistake: if the capabilities of computers continue to multiply while the price of computing continues to decline, that will mean a great many of life’s necessities and luxuries will become ever cheaper, and it will mean great wealth—at least when aggregated up to the level of the national economy.

But even leaving aside questions of how to distribute that wealth, the widespread disappearance of work would usher in a social transformation unlike any we’ve seen. If John Russo is right, then saving work is more important than saving any particular job. Industriousness has served as America’s unofficial religion since its founding. The sanctity and preeminence of work lie at the heart of the country’s politics, economics, and social interactions. What might happen if work goes away?

What if work as we know it ends? Is a life without work even a thing that is remotely possible or desirable given who we are as humans?

My own sense of where we’re headed as a society is somewhere closer to the McCrindle prediction than the Atlantic’s post-work future. Christians may well be excluded from ‘traditional institutions’ in this future because of our convictions, but these institutions might themselves have been disrupted (or marginalised). I’m also optimistic that our Christian convictions, and a more imaginative, non-status quo, vision of humanity, work and the world might lead us to be innovators and ‘creatives’ who benefit from these changes (though perhaps those benefits won’t be felt in economic terms). There is an opportunity, if the McCrindle conclusions are right (and even if the future looks more like ‘post-work’) for Christians to be disruptive in ways that reflect our rejection of our world’s status quo when it comes to the place of work in a materialistic, idolatrous (greedy) culture built on consumption and perpetual productivity growth. Part of us being truly disruptive will rely on us, as Christians, training a generation of innovators and entrepreneurs who look for opportunities to disrupt; particularly opportunities born out of our convictions about what is wrong with the status quo; particularly our society’s understanding of what work is, and what work is for.

But this might require us re-tooling the way we understand work in our world, and our place in it; it’ll definitely mean we need to be disrupted first, so that we’re able to spot the ways in which the idolatry of our age has crept into how we approach work, including the work we do, and why we do it. In this series I’ll unpack some more on the nature of work and what drives us to work, what the ends of work are (as opposed to the end of work), and think about how we might approach the future of work as Christians with a hopeful optimism and a desire to disrupt.