One of the most telling things about many of the conversations I’ve participated in and watched around the ABC expose on domestic violence in churches in the last week is around the place we Christians seem to want to occupy at the common ‘table’ and the way we then operate our own ‘table’…

A tale of two tables

Bear with me. I’m going to use the table as a metaphor for where these conversations happen. Let’s assume for a moment that the public square is like a dining table; lots of people with ideas clamour for seats. For a long time, in Christendom, the institutional church had one of the prime positions (if not the prime position for a while) at this table. We set the agenda; we were the hosts; it was assumed we would look out for the common good. Over time our place at the head was contested, and we moved away from the head but remained in a position of influence. We were still heard. Now. Well. The table is both ‘secular’ in that our voice doesn’t get a particularly special place, ‘pluralistic’ in that many voices — institutional, and even religious — are welcomed, but there’s increasingly an expectation that religious beliefs are a bit out of touch and probably don’t have much of a place, and we’re tolerated so long as we’re prepared to put our money where our mouth is and act to bring change according to an agenda set by the host.

There’s a second table in this metaphor. It’s the table that we run. The one where we invite other people to be part of discussions; where we are the host, and where we should be particularly interested to invite people that the rest of society ignores. Historically this has been where the church has been an excellent force for social change; because the conversations at this second table have informed our participation at the first. But mostly because this table is where we see the power of the Gospel to generally bring people together as family; where the worldly games of status and power get put aside (incidentally, this is why Paul is so keen to rebuke the way status games are creeping in to the share meal in Corinth)… Our literal table is meant to be different as an expression of this metaphor. If the first table is the public square, and the banquet is the communication that happens there; the second is our Christian community and the conversations that happen there. How we approach the first table as leaders or the ‘institution’ shapes the tone of the second, and who feels welcome (because in fact, how we approach the first table should reflect who is speaking at the second).

The dilemma is that not only have we lost our place of honour at the first table — now it’s a place where we’re increasingly losing our dignity. We’re now viewed with the sort of suspicion reserved for the slightly delusional great-uncle at a family gathering. There’s now increasingly a belief that we’re not just delusional but harmful and unwelcome. So we protest like that same great-uncle would about being shunted down the line, replaced by new in-laws, out-laws, and Johny-come-latelys. We’ve lost a bit of status and dignity. We’re really worried about losing our seat; and so we act out a bit, yell loudly about our historic contribution, and forget that a big part of our value was what we brought to table one from table two; that those contributions were noticed and gave us legitimacy. And yet, we do still get seats at the table; our lobbyists are heard, and invited onto TV panel programs, so too are pretty exceptional representatives of the clergy and the church; who are invited to contribute to discussions.

I’m not the first to use these two tables as a metaphor; Jesus was. But more recently there was a great article in Cardus’ Comment Magazine that planted this idea for me. Here’s a bit from Luke 14, where Jesus has been invited into the house of a Pharisee; to dine at the table of a ruler of the pharisees. This is the public sphere; and Luke tells us ‘they are watching him carefully’… it’s the sabbath. And Jesus heals a man with dropsy; an outcast. A man whose illness and physical disfigurement would’ve excluded him from the sort of power and influence his host enjoyed. And at this table, there’s a competition for top spot…

Now he told a parable to those who were invited, when he noticed how they chose the places of honour, saying to them, “When you are invited by someone to a wedding feast, do not sit down in a place of honour, lest someone more distinguished than you be invited by him, and he who invited you both will come and say to you, ‘Give your place to this person,’ and then you will begin with shame to take the lowest place. But when you are invited, go and sit in the lowest place, so that when your host comes he may say to you, ‘Friend, move up higher.’ Then you will be honoured in the presence of all who sit at table with you. For everyone who exalts himself will be humbled, and he who humbles himself will be exalted.”

He said also to the man who had invited him, “When you give a dinner or a banquet, do not invite your friends or your brothers or your relatives or rich neighbours, lest they also invite you in return and you be repaid. But when you give a feast, invite the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind, and you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you. For you will be repaid at the resurrection of the just.” — Luke 14:7-14

It feels to me like we Christians are getting bumped down the pecking order in that table of influence; further and further away from the place of honour. And we keep grabbing a seat that’s about where we think we should be and being dropped a peg or two; and the way back up isn’t to noisily defend our honour; but to act with honour and dignity; to present ourselves as more lowly than we actually are… and there seems to be a connection between this picture and the one that immediately follows of hosting a banquet. This is a picture of the sort of literal and metaphorical hospitality we should be offering in this world; of our priorities in terms of the sorts of people whose voices we should be concerned about at our table.

When it comes to the Domestic Violence conversation, here’s where I think our approach to the dilemma we’re more broadly experiencing around our place at table one kicks in. We’re so keen not to be the crazy uncle, we’re so keen to keep our place at the table, that we lash out at anybody who has the temerity to suggest that there is anything at all wrong with us that should keep us from the conversation. Like the crazy uncle who keeps turning up in his underwear and thinks there’s a great conspiracy to get rid of him when all the rest of the family want is for him to wear pants and behave with common decency; and to stop trying to sit at the head and dictate the conversation for everybody else.

This is what it looks like to me when we keep going after the ABC for ‘bias’ or as though there’s an anti-Christian agenda behind this story or its use of stats (which I do believe were a very minor part of the investigation and the story, they were just the controversy used to sell the story). And News Ltd isn’t helping (nor is our ongoing desire for the institution to be vindicated by the court of public opinion). They’ve found a wedge in their ongoing stoush with the ABC and they’re using the figure of the great uncle to score points against another voice at the table. Every time we try to land a blow on the ABC we’re failing to ‘turn the other cheek’ or to respond to curse with blessing. Every time we clamour for a spot at table one by asserting our dignity and our rightful place there, we’re making table two seem less hospitable to the victims in our communities.

We may well have been misrepresented — certainly the headline and hook sentence of that first article (probably written by a sub-editor, not the reporters) was unhelpful, and Media Watch has rightfully critiqued the ABC’s coverage for that… but what we’re not considering in our attempts to maintain an honourable position at table one, is what the cost is to our ability to run our second table; to being hospitable and welcoming to those we should be hospitable and welcoming to.

Table two should be our primary concern. Table two is the table where we should be making space for the victims; the vulnerable, and the oppressed. And so many of those women, on social media, are reporting that our concern to maintain face and dignity at table one — institutionally — to protect the brand — is coming at a cost of them feeling welcome at table two. Our leaders have been so quick to share criticisms of the ABC article, its methodology, its headline, its use of ‘research’ (and I use those quote marks deliberately because on the one hand we’re dismissive of the year long investigation of actual stories in Australia, and on the other hand I think research from America a decade ago is of questionable value in assessing the Australian scene anyway); and this, in my observations, has been from a desire to maintain the dignity of the church and keep us getting a place at the table. I think it’s a wrong strategy. I think it’s harmful for our table one status; and disastrous for our hosting of table two. And we need to assess our priorities. And the way to do that is to listen to the people who are at our table with us — or should be — the victims; be that in the stories Julia Baird unearthed, or the many victims who’ve come forward on social media. One of my Facebook friends, Isabella Young, is a victim and an advocate for victims in the church; she said the other day:

“This appears to be turning into the rest of the church versus the abuse victims unfortunately. I really don’t care what those stats say, what I do care about is that no one is discussing the individual points raised in the article or documentary. But we all like a fight don’t we?”

Our job is to be the hosts of this other table that is utterly different to the table of the Pharisees — the tables that operate in the world of power and status. Jesus returns to the idea of places of honour at banquets a bit later in Luke’s Gospel.

“Beware of the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes, and love greetings in the marketplaces and the best seats in the synagogues and the places of honour at feasts, who devour widows’ houses and for a pretense make long prayers. They will receive the greater condemnation.” — Luke 20:46-47

This is a picture of the status hungry gone rogue — people who in pursuit of their own honour also devour widows houses. People who should be hosts but are wolves and abusers of the vulnerable. That’s what we’re not to be; people who are so concerned with our own dignity and place at the public table — these ‘feasts’ — that we are destroying our ability to be hospitable to the vulnerable.

I reckon that’s a key to this role we’re meant to play as generous hosts to the vulnerable, who are then able to represent the vulnerable well as advocates in other spheres. I suspect the closer we are to the head of table one — the more proximate we are to worldly power — the harder this passionate advocacy is to achieve; much like it would have been harder for Jesus to challenge the Pharisees if he was one. Our relationship to worldly power should be the same, I suspect, as his relationship to the Pharisees; an expectation of crucifixion for calling out when that power is being abused. It’s hard to do that if we’re at the head of that table, or our relationship is too cosy, or if we want to be treated with dignity and respect; rather than seeing our mission as speaking on behalf of those at table two. Our table.

Here’s the thing. Realising that we’re not at the head of the table, or in a place of honour, any longer at table one is vital for our ability to do public Christianity; or participate in the public square; with dignity. Self-protection is a lot like aiming for a place of honour that we don’t deserve; having others protect our dignity is not an opportunity for us to say “I told you so” — if it happens it is nice, and we should be thankful, but turning the other cheek means we don’t use another person’s testimony in our favour to hit back.

Realising we’re not the host of the public conversation also guides the way we contribute to the conversation; its not our conversation to run, it’s not our job to define terms, or to be defensive; our best ‘defence’ is who we host at table two, and how we speak for and look out for their interests. That’s where we gain credibility; that and in our humility which is expressed in treating our host and conversation partners with respect even when they wrong us; even when they’re trying to trap us; even if ultimately they’ll crucify us. That’s what Jesus was doing in Luke 14, even as he implicitly rebuked the Pharisees by healing the crippled man on the sabbath; as he explicitly rebuked them by suggesting his host and guests had their approach to hospitality and honour wrong, and building a table for “the poor, the crippled, the lame, the blind” is what Jesus came to achieve; the table he builds is the table of his kingdom; these people are tangible pictures of those who know they need God and salvation in Luke’s Gospel — Jesus has previously proclaimed ‘it’s not the healthy who need the doctor, but the sick’ (Luke 5:31), and these are the people Jesus explicitly said he came to liberate in Luke 4. This is the sort of table we’re to be building in our own communities; and our efforts in the last few days, in many cases, have been deconstructive rather than constructive.

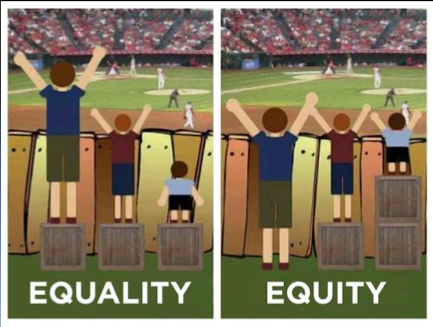

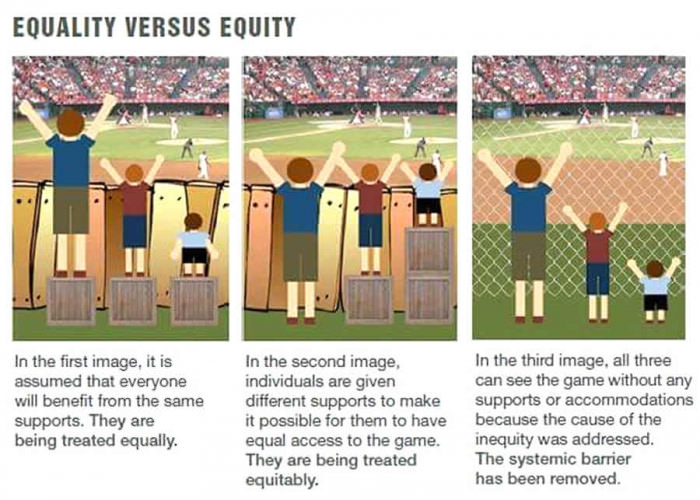

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As