My association with Eternity News, such as it was, began in 2009 (Tuesday the 4th of August to be precise — I keep all my emails thanks to the wonders of gmail). On this auspicious date the founding editor (and founder) John Sandeman emailed me to tell me someone’d suggested I’d be moderately “good at collecting off the wall internet stuff at least vaguely about Christianity.”

I wrote back: “Sounds good. Count me in.”

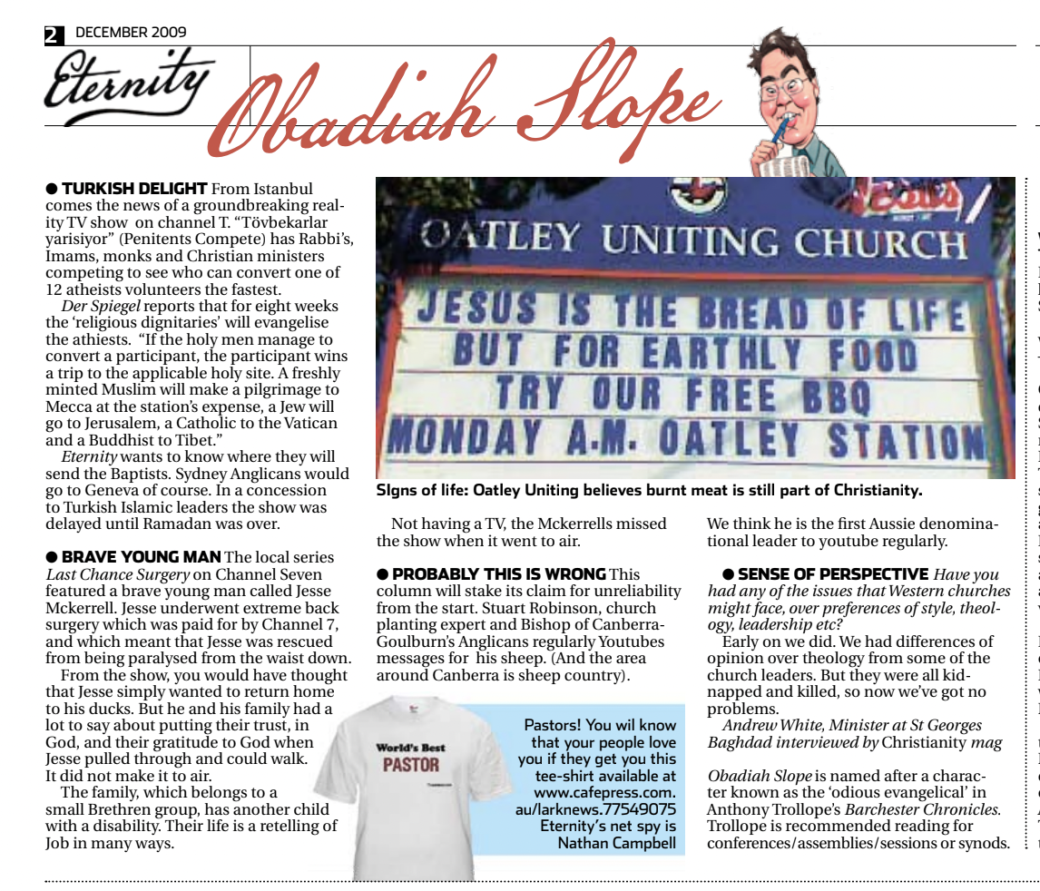

That was basically the core business of one of the earliest iterations of my blog, and I must’ve given it a go at least once, because, right here in the Obadiah Slope column from Eternity’s second print edition I’m named as Eternity’s “net spy,” that was right about the time the gossip column in the local paper in North Queensland (the Townsville Bulletin) had called me a “PR Spin Twit” in a hatchet job on my CEO, so “net spy” was quite flattering and an association that would last over a decade was born. Here’s a PDF proof John sent me of my first cameo in the paper.

In our email back and forth, as John sounded me out on what sort of correspondent I might be, he outlined his vision for Eternity (as well as being a proper print news outlet), and why I might get on board sharing stories from the far reaches of Queensland. He said:

“We need to report on what God is doing in Queensland. Occasionally we will have to report a church split or something negative, but we really want to dig out the good things that are going on. People stories, new movements, old churches stirring, reconciliation, church plants, Christians campaigning for social justice, and against bad stuff.”

I believed then — and I still believe now — that a news outlet reporting on these stories not just in Queensland, but around Australia, is a good thing for the church. At various times in Eternity’s history I was a Queensland correspondent for a locally focused section of the print edition, where I was even described as “Eternity’s Nathan Campbell” — an upgrade from “net spy.”

I’ve waxed lyrical about Eternity’s broad table approach to reporting — and opinion columning — in the polarised church and media landscape we find ourselves in, and was a supporter of a shift in content strategy towards sharing ‘seriously good news’ they made after a review in around 2015 (see John’s comment on this post of mine, I had a great phone conversation with the review team, that I still remember, standing in the carpark of a hospital in Brisbane). I said then what I’ll say now — the Aussie Christian media landscape needs less echo chambers that draw boundaries, and more platforms that host conversations between people who disagree. I recognise that its table was not as big or inclusive as people in the progressive arm of the church would like it to have been (the comments section on any Eternity article on Facebook made this clear, so did the boycotts, typically from friends of mine on the Christian left). I recognise too that the decision to include voices from the Christian right in recent years, while excluding the left (with a boundary drawn around sexual orthopraxy rather than creedal orthodoxy), caused significant controversy.

The recently announced change in direction at Eternity saddens me for a whole host of reasons. Australia is not a huge media landscape in itself, but the Christian publishing section of the market is even smaller. And I’d love us to have institutions like Eternity to report on the sorts of things John had Eternity reporting on from its earliest days. I’ve been an enthusiastic supporter (and contributor) to Soul Tread, a print only Christian publication (that has recently published edition 7) for exactly this reason. I was struck by the editorial review of my first piece for Soul Tread, where the editor pointed out that much of my writing online is given to deconstruction, and analysis, of problems in the church while she’d love me to articulate a constructive vision for an alternative. I love a good editor. And John, and his team at Eternity have been that for me. Eternity has offered a platform for seriously good news, and for both deconstruction and construction.

I have made much of my early association with Eternity above, but I was never as connected to the project as I’d have liked — it’s not my day job after all, and I have three young children who rightly demand my attention. And at this point I want to insert a disclaimer, cause, right now, I’m going to engage in some of that deconstruction I’ve just mentioned above. And I want to make it clear that this is speculation from a passionately interested, and kinda connected, outsider — writing as a blogger — rather than inside knowledge backed up by investigation and evidence. It is opinion. It comes from someone who wants to see story telling organisations like Eternity succeed as something more than the advertising arm of a Christian institution (no matter how noble that institution — seriously, I’m not here to paint the Bible Society as the bad guy in this story).

I’m thankful, for the team’s investigative skills and courage and the way they’ve tackled significant stories in the life of the church, and for John’s stewardship of a section of the public conversation about the church in Australia. If you look at my ‘author’ page on Eternity (screenshot below), I’m thankful for the mix of articles of mine they chose to publish over the years (they’re not all here, cause some were in the print era). I think they were bold to publish some of them, and, to some extent, I was probably the most progressive columnist in their network — right back from when they published my list of reasons I would not tell people how to vote in the plebiscite. John has rightly always been keen to point out my conservative credentials too — I remain an ordained minister in one of the most theologically conservative denominations in the country.

I believe the decision at Eternity to broaden the table from centre-to-centre-right to include voices from the hard right was made, so far as I can discern, as the beginning of the end of what, in newsrooms, is called “the separation of church and state” — commercial imperatives (the state) should be kept at arms length from reporting content (the church). There was obvious pressure being exerted on the Bible Society, and so on Eternity because certain groups in the Aussie landscape perceived, in its centrism, a ‘woke bias’ — while, at the same time, my friends on the left were boycotting Eternity over stories around race and sexuality. This, I believe, led to the inclusion of new columnists as proof that Eternity was not a lefty rag devoted to fomenting woke politics and the social Gospel. I am aware of the consternation this caused the existing stable of contributors to Eternity — because I was one, and because of group chats. I believe it placed the ‘church’ part of Eternity in an invidious position, and the pressure they were placed under from the Christian left and the Christian right is, I think, proof that the newsroom was fulfilling a ‘mediatorial’ role of sorts. There was a certain sort of integrity that meant the same invitation to contribute opinion columns was not extended further to the left — something John discussed in an editorial — but, here’s my speculation — let’s call it me being a ‘net spy’ again — I wonder if the push to include voices from the hard right was a test of integrity that the newsroom could not bear as the ‘state’ started exerting more pressure. If Eternity is a victim of the very culture war it gave space to report — and to call out.

The evidence that sends me towards this hunch rests on the article I wrote for Eternity that you will not find on my author page. In early March 2021, as Eternity began platforming conservative writers like James Macpherson (March 2), and as these group chats between contributors exploded with concern that the nature of the platform might be shifting under this pressure, I pitched and contributed a piece to Eternity with the aim of proving the ‘big table’ vision had legs, and that maintaining a connection and challenging presence in response to the pieces by Macpherson, that courted a market further to the right, was a better response than a boycott. My piece came off the back of the Church and State conference in Queensland last year, and the associated media coverage.

It named, and linked, speakers platformed on that conference to a hard right movement — connecting the dots to institutions (like the conference and Caldron Pool), it suggested that in the fallout of January 6, hard right voices in Australia calling for revolution and joking about violence in the context of a “war” against ideological opponents were not offering a helpful Christian contribution to our political life, and, it invited those I named to the table, and to conversation, rather than to the fight. I named names because there was a piece in the Caldron Pool about ‘wolves in the Presbyterian denomination” that had been written about me, but where the author (another Presbyterian minister, who I named in the piece) refused to actually say he was talking about me. I don’t believe the sorts of conversations that are life-giving and transformative should operate without speaking truthfully and directly. I took that risk. I sourced my info. I framed what was opinion as opinion. And John backed me — he published the piece — because Eternity had a commitment to not being an echo chamber, and to hosting a conversation John believed was important for the good of the church — whether he agreed with me or not, who can say.

It’s fair to say that the reaction to the piece was not, in the main, people from across the aisle joining me at the table (I did sit down for breakfast with Church and State’s Dave Pellowe). Instead, it lead to threats of lawsuits against Eternity, and me, especially from Caldron Pool’s founder Ben Davis; to pressure being put on the ‘church’ part of Eternity by the State, and so, after a conversation with John, I decided to apologise — not for the content of the post, which, as I say, was meticulously sourced and still represents my opinion (since born out in Caldron Pool’s involvement with Freedom Rallies) — but for some of my bombastic tone, and for the way it fed the very polarisation it was attempting to name, and we decided to withdraw my piece rather than rewrite it, as an olive branch. Maybe we caved. Maybe we modelled something good that the piece itself invited in an attempt to get people across a divide to the table. In the end it didn’t appease the critics. It turns out those who are most outspoken in favour of “courage culture” and against “cancel culture” are some of the quickest to threaten to bring in the lawyers.

The decision to pull my piece caused a mini-outcry on the Christian left, and I saw several posts (and received messages) arguing that John should have backed me harder. John is not, in my estimation, one to shy away from a fight — I apologised publicly, and maybe too quickly, and left him on the hook for what he’d published in my name. I want to make it clear that I jumped first, and left John holding the grenade. And I regret that now. I even published my apology/retraction here on St. Eutychus while waiting for John to get back to me on a joint apology because of how quickly the situation was escalating. I recognise that caused him an awkward and vaguely frustrating conundrum in the difficult internal landscape Eternity was navigating. The apology and withdrawal was at my initiative, and I’m convinced that the furore created by my piece publicly was echoed privately, in the church-state relationship at Bible Society (I have some other pieces of the jigsaw puzzle here from people adjacent to Eternity that lead me to suspect this).

If my piece was in any way a lightning rod, a part of, or a catalyst for the trajectory that sees the Bible Society take these steps to make Eternity a promo-mag for its activities, then I’ll feel the weight of that. I don’t want to overstate the way this episode is maybe a microcosm of what I’m speculating caused this step, but I do recognise that platforms and agendas much bigger than mine have been exerting much greater pressure on the ‘state side’ of the business (see, for example, this piece from Caldron Pool by the Presbyterian pastor my piece named asking “When did the Bible Society Lose Sight of Eternity“). Let me engage in a little more speculation here — this sort of pressure — negative press — was hardly likely to help the Bible Society achieve its mission to a much broader table than Eternity’s readership and editorial agenda was reaching (and was likely to do it harm by making it a political football). And again, getting the Bible into the hands of people across the political spectrum, and any cultural divides, is a significant and important mission of eternal significance — the link with Eternity’s mission, and its willingness to host controversial conversations and highlight stories of failure was never a good fit. The state was always going to have to put at least equal and opposite pressure on the church…

Now, I might be wrong about all the behind the scenes stuff here, but there’s plenty of public commentary about the move that suggests others — on the right and left — are interpreting the decision through a similar lens.

There’s a couple of old sayings that gets bandied about for journalism students: “the media is a mirror,” and “we get the media we deserve.” These are increasingly axiomatic in an age of poll driven publications trying to remain viable in a diversified/fragmented market, where publications now ‘give the readers what they want’ rather than stewarding a role in the public conversation where they give us what is true, and oriented towards the public good. I’m also scared that with Eternity’s shift into advertorial we, in the church, are getting the media we deserve — that this shows we aren’t mature enough to have nice things. That our tribalism, conflict, and culture wars have overwhelmed a beautiful vision from an old school media man who wanted to “dig out the good things going on” and tell the stories about the work God is doing in Australia, through his people.

For now I’m thankful for Eternity’s role in the story of the Australian church; and its telling of stories from the Australian church. I’m thankful for the team of editors, writers, and outside contributors who caught the vision, and I’m praying those who’ve taken redundancies as a result of this shift find alternative channels for their gifts. I want to honour the contributions of those I’ve worked with, and especially, John’s vision.

I’m prayerfully hopeful that something good might emerge from the death of Eternity; that we’re not simply going to be left with a fragmented Christian media landscape of 2-bit bloggers (like me), echo chambers, and blokes hurling grenades from self-constructed bully pulpits. Friends have issued a couple of ‘watch this space’ messages that have whet my appetite here, with nods to a news outlet operating with an even broader table than Eternity’s.

Eternity has a special place in my heart. And it, like everything God has made, was beautiful in its time.