This was talk nine, and the final talk, in a series preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2024. You can listen to this sermon on the podcast, or watch it here.

We are at the end. How have you gone with all this picture stuff — engaging your imagination — your ability to make images — if you have that ability — as we have worked through these images of heaven through the Bible together?

We started out with Paul’s prayer in Ephesians — that the eyes of the heart of his readers might be enlightened (Ephesians 1:18). If you are joining us, we have been leaning into this idea from Paul, and it is just worth recapping as we set the scene today. His prayer is that we might know the hope to which he has called us — the picture of the future that drives us. This is what hope is really; an imagining of a good outcome that shapes how we live. Paul speaks of this as the riches of his glorious inheritance in or for his holy people.

He has already unpacked a bit of this earlier in his introduction to this letter where he talks about God’s plans and purposes that he has revealed in Jesus Christ (Ephesians 1:8–9). He speaks of God’s plan for the fulfilment of time — where he will bring all things in heaven and on earth together in unity under Jesus. This is what we read John describe in his vision from Revelation. This is the hope Paul wants our hearts to be captivated by; what he is praying we will see.

In another letter — Colossians — Paul talks about God having all his fullness dwell in Jesus, and through him all things being reconciled — being brought together in harmony — whether that is on earth or things in heaven, or heaven and earth. This is secured, ultimately, through Jesus’ blood shed on the cross (Colossians 1:19–20).

The Son of God who reigns in heaven is reigning with the purpose of bringing heaven — where God lives — and earth — together. This is what that video from the Bible Project covered — the idea that our hope, the trajectory of reality as the Bible describes it, is heaven and earth coming together as one eternal reality where we dwell with God.

We have seen that Paul says in some way this is not just our future, it is our present. Those who have received God’s Spirit so we are united with Jesus where he is now, have been raised and seated with him in the heavenly realms — we have been located in heaven (Ephesians 2:6).

So we live on earth as walking temples, where God dwells on earth (Ephesians 2:21–22). We are walking, talking, imagining, living, serving pictures of the future of all things; those who have been reconciled to God, and to each other.

Paul says because of all this we can approach God with freedom and confidence — this is what we do as we pray — we approach God in this heavenly throne room (Ephesians 3:12). This is what Paul was doing for the readers of his letter as he prayed that the eyes of our hearts might be enlightened. This is the reality he was seeing as he prayed that his readers would see.

It is the reality he was encountering in a prayer we will come back to as he describes himself kneeling before the Father from whom every family in heaven and on earth — all the beings who will be brought together — derive our name. That is a way of saying we owe our existence and role in the cosmos to him (Ephesians 3:14–15).

Paul ends that prayer in Ephesians 3 with this idea that even as he is kneeling before God, imagining the splendour of the throne room of God — coming before the throne — even then our imaginations are limited. We are not getting the full picture of this reality of our hope in God’s goodness. God can do immeasurably more than we can ask or imagine according to this power he has described — the power that has raised and seated us and that will reconcile all things (Ephesians 3:20–21).

Our imaginations will fall short, and the eyes of our hearts are always up for more enlightenment; more contemplation or imagination of the future; of our hope, through more time before the throne of God. This is so that we are more and more caught up in this calling to be living temples — heaven on earth people living in this overlap, anticipating and picturing the future in our imaginations and our lives.

There is this idea that we can spend so much time thinking about heaven as Christians that we become no use on earth. We sometimes see this in how Christians write off pursuing justice in political issues in this world, or speaking up — trading off doing “earthly stuff” against investing in evangelism — proclaiming the Gospel. Or in how we think about climate change, where maybe you have heard Christians say “it is all going to burn up so we should focus on saving souls.” Or maybe it is the idea that hope is a sort of naïve optimism that stops us confronting reality as it really is, and seeing the suffering not just in our lives, but in those around us as a serious indication of something deeply wrong with reality that should leave us grieving or crying out for justice.

But I think the opposite is the case. I think the more we spend time imagining this hope — an earth reconciled and connected to heaven — and see our calling as living like heaven on earth people, the more this time dwelling with God before his throne in prayer and worship, cultivating hope, will translate into lives that embody this hope now. It will shape lives that pursue a picture of heaven-on-earth life, and a hopeful vision of the future that frames how we suffer differently, and how we enter the suffering of others.

So the working theory this morning is that we maybe do not spend enough time hoping and picturing this future — we do not spend enough time before the throne, contemplating heaven. We would maybe be more useful on earth if we did, and even more effective in our evangelism. Priests in the Bible — those sent out to carry God’s presence in the world — are shaped by time spent in that presence; by understanding the God we represent. The working theory for this morning is that the more time we spend dwelling in this hope — imagining it, picturing it, meditating on it, prayerfully cultivating a sense of who God is, the God who will always be immeasurably beyond our imagination in terms of his goodness and love, the God who is committed to this reconciliation, this heaven-and-earth future — the more meaningful and purposeful our life on earth will be, and the better our witness will be to the world.

This is how John’s vision works in the first century. He is writing to Christians facing incredible suffering, looking at Rome enacting its vision of heaven on earth, tempted to jump ship and worship the emperor and enjoy the fruits of the empire, tempted not just by the carrot of sharing in that power and beauty but the stick of being set on fire as candles in a garden party if they do not. John’s vision of heaven is meant to reframe their reality, to hold them fast to Jesus, and to expose this Roman empire as a false, beastly, destructive vision of heaven — so they will live as faithful witnesses; God’s church, his kingdom of priests.

John’s vision ends with this picture of the end — of heaven and earth made new, the old passing away, and there is no longer any sea (Revelation 21:1).

Now — for those of us who love the beach — I do not think this means there is no more Sunshine Coast. The sea was a picture of chaos and destruction — think about the waters at the start of the story of the Bible. But in the context of heaven and earth — the sea is also that barrier separating the heavens and the earth — the crystal dome under the throne of God (Exodus 24:10; Ezekiel 1:22). Moses goes through it at the top of the mountain; Ezekiel sees it above the cherubim who are carrying around God’s throne, and it is in that giant bowl in the temple.

John describes this sea of glass in front of the throne earlier in Revelation (Revelation 4:6). I think we are meant to imagine this as the vault from Genesis 1 that separated water from water (Genesis 1:6–7). It is the dome God opened up to send the flood in the Noah story. For the ancient reader who did not have telescopes or spaceships, this was how they imagined a real physical barrier between God’s realm and ours in the sky. And that barrier is gone.

Because that barrier is gone, the holy city — the new Jerusalem — can come down from heaven into earth (Revelation 21:2). The new Jerusalem, this heavenly city, is the predominant image from what we read together. It is this heavenly city that ties all the images from our series together — the light, the mountain, the garden, the temple, the throne in the holy of holies where God acts as judge and king, and the dwelling place of the Lamb of God — the Son of God, the bridegroom as Jesus describes himself in John’s Gospel. Here we are meeting the bride — this city — prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. This is a picture of Jesus being united with his beloved church, a permanent union between heaven and earth.

A voice comes from the throne to interpret this image for us — “look, God is dwelling now with his people; the barrier is gone. God and humans are reconciled in this new heaven-meets-earth space” (Revelation 21:3). He comes as the God whose hands are outstretched to wipe away every tear from our eyes. He comes as the God who defeats all the things that harm us and separate us from God (Revelation 21:4) — no more death, or mourning, or crying, or pain, for the old order of things is dead and gone.

The one seated on the throne says, “I am making all things new.” All the sad things are coming untrue (Revelation 21:5). This is our hope, and the one on the throne says it is trustworthy and true.

Do you believe it? Can you conceive it in your imagination? Just take a moment. What would that mean for your life in the future? What does this look like, beloved of God — to dwell with him, to have all the remnants of sin and death removed from you, your grief and pain wiped away by the God who loves you?

Can you picture a hand wiping away your tears and with that swipe, removing the burden of everything you have done — and everything done to you — so that guilt, and shame, and trauma, and wounds are dealt with? These barriers that have left you feeling separated from God, feeling unworthy — gone. That shame you feel because you never measure up to your own standards, let alone the standards of others, even if only you know it. The harsh and violent words and deeds shouted in your face, or maybe worse — whispered. The indifference you have felt from those who should love you, the contempt. The never feeling like you belong. The guilt you carry because you have done the shouting, or the whispering, or the violence, or the contempt — the way you have consumed others in darkness, even just in the darkness of your imagination — dead, wiped away, as you are made new.

I know I need this picture. I know I need the comfort it offers. All things new. How might that hope shape your now?

Jesus — the one who was dead, and is now alive — joins his Father enthroned, and offers the water of life from this heavenly spring, to bathe in and be cleansed, to drink and never be thirsty — for free, without cost (Revelation 21:6).

This is what Jesus offers to those who are victorious (Revelation 21:7) — those who come to the throne and cling to him and worship him and are not lured into life — or death — with the beastly empires and destructive powers of heaven. The darkness. Children of God.

This newness can only happen as the old order is destroyed — which includes those powers committed to visiting violent suffering on others; those who have not been transformed by encountering God’s hand stretched out in embrace. They experience exclusion. This is uncomfortable for many of us, and we might hope that God is going to do that transforming work in every person whether we see it or not. But this pattern of death cannot exist in this new creation, and so the patterns — and those who live by them — are destroyed in the fiery power of the throne, in the second death (Revelation 21:8).

We might want to dwell on this idea, and it might devastate us to imagine this happening to us, or to our beloved — and I suspect it should. We should grapple with this as humans — humans who know we bring nothing to the table when it comes to God extending his embrace to us through Jesus. We know that we fall before the throne deserving whatever fate our neighbours experience. This is part of the vision that should motivate us to live as priests of the reconciling God who wants to bring all things to Jesus.

The marriage of the Lamb is totally consensual. He will not force those who reject him into this relationship, and this peaceful future cannot happen with those totally committed to ways of death that come from rejecting God, and God’s vision for life, destroying others in pursuit of their visions.

But we are not dwelling on that picture in John’s vision. John’s eyes are swept up, and so are ours, to examine this bride — the wife of the Lamb (Revelation 21:9–10). Here is where images we have contemplated come thick and fast. For starters we are on the mountain — great and high — seeing this holy city coming down, shining with the glory, the bright light of God (Revelation 21:11). It is bright like the jewels we saw in the prophets and earlier in Revelation — shining.

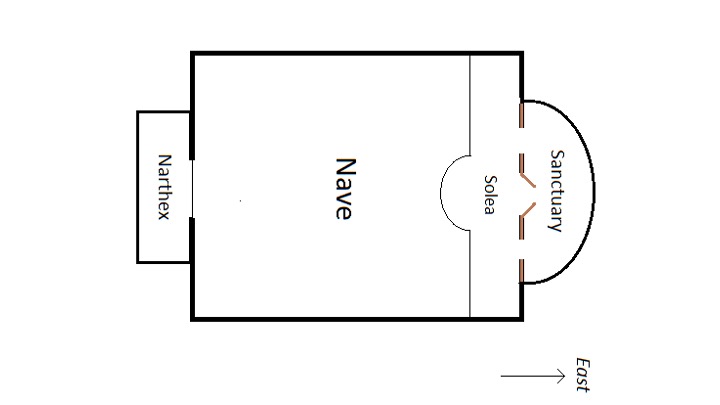

It has twelve gates. There are lots of twelves — it is a picture of completeness, like the twelve tribes and the twelve apostles — and there are twelve angels as well. It is a picture of heaven and earth coming together in this sort of fulfilment — filled up (Revelation 21:12). Then we start to get the hint that this city — the whole city — is a temple. Where the old Jerusalem contained both the temple and the palace so that God ruled from his throne and the Messiah from the throne in the palace, here there is one throne room (Revelation 21:15–16).

We are getting this tour from an angel who is carrying a measuring rod to help us see how this city is a square. This is a throwback to Ezekiel’s vision — also on a very high mountain — of a new temple in a city on a mountain (Ezekiel 40:2). Ezekiel also saw a heavenly figure with a measuring rod, as he saw a square-shaped building (Ezekiel 40:3). John is seeing a square-shaped city — it is huge, overwhelmingly big (Revelation 21:16).

Just as the temple in the Old Testament was covered in gold, this city is pure gold (Revelation 21:17). It is covered in precious stone, like the throne room of God. There are twelve walls with twelve types of jewels, and just in case you think “there is no such thing as twelve different jewels” — or if you are skeptical — John names them all (Revelation 21:19–20).

The gates are pearly. There is that sort of memey joke where we are meant to imagine ourselves standing before the pearly gates wondering if we get in. That is not the point here. Those united with Jesus are already in, and have already been behind the walls through the gates, in the city of gold, as those seated with Jesus (Revelation 21:21).

Because behind these walls there is no temple. This is a temple city; this is a holy of holies city. This is where God dwells. The Father and the Lamb “are the temple” (Revelation 21:22–23). This is where God’s throne is now located. The light is emanating from them. It does not even need the sun or the moon — those heavenly bodies that reflect God’s light and help us picture it. We are invited to imagine Father and Son as brighter than the sun, providing light to the nations. All the kings of the earth in this new reality — who do not serve beastly powers, but God — bring their splendour forward in worship of the one seated on the throne. They give as an act of worship, and the gates are open because there is no longer an enemy. There are no wolves lurking around at night waiting to do harm, that would make you shut the gates (Revelation 21:24–25).

Nothing impure will come in, nor those excluded who do what is shameful or deceitful. Only those whose names are written in the Lamb’s book of life — those pulled out of death into life through Jesus’ blood, his death that makes peace and reconciles all things, offering reconciliation between us and God as heaven and earth are brought together (Revelation 21:26–27).

Then we get both a throwback to Ezekiel’s vision of the water being released from the temple, living water turning the earth into a fruitful paradise, and to the garden of Eden. Garden imagery is bursting out. We do not need gold carvings in a temple building, this is a picture of the real thing. The river is flowing through the city — like the waters flowed out of Eden and into the world — out from the throne. Not rivers of fiery judgment but watery life. Not a crystal sea working as a barrier, but life flowing from the throne (Revelation 22:1–2).

As the water flows, trees grow — especially the tree of life. It bears fruit constantly, monthly, giving life to all who dwell with God, and its leaves heal the nations, bringing peace and tranquility (Revelation 22:3). No longer will there be any curse. Nothing is separating us from God, from life in this place. We are no longer exiled from the tree, or from the gardener who plants it. Life is no longer secured through toil in a world turned against us (Revelation 22:3–4).

The throne is there and we will live before it, as God’s people, serving him. That is a worship word. He delights in giving light and life and love to us. We will see his face — a heavenly encounter impossible to conceive fully in the Old Testament, hinted at in the life of Jesus as people saw God’s glory in human flesh. Again — no more night, because God will give light, and he will reign forever (Revelation 22:5).

This is earth — all the goodness and wonder of God’s creation, heaven-on-earth spaces, being fused with heaven, all the glory and wonder of God’s throne room, and the heavenly human who rules on the throne with God, being brought together.

This is the story of the Bible — this is our hope. It seems beyond our capacity to fully comprehend, right — and I think all of this imagery is analogy — giving us images and language to shape our hope. At the heart of this hope is life; intimate life with the God who loves us and will make us new, and will give us life with him and with each other forever.

But it is not our present. Our present is life in this now and not yet. Now those who have God’s Spirit dwelling in us, so that through us — God’s living temple — God lives in the world. We are those who are reconciled to God and are a picture of heaven and earth being reconciled as we inhabit space and time. We are those who are raised and seated and can come before the throne of heaven — with all this splendour surrounding it — in prayer and worship, so that we carry the presence of the God who rules into the world. With the hope that all the curse, and tears, and pain — will pass, must pass — and that all things will be made new as we are being made new.

So what difference does this make for actual life on the ground? What difference do all these pictures make for us?

Well, for starters, I think, this changes how we understand and articulate the Gospel, and how we live as those who believe the Gospel. The Gospel is not just about our souls escaping to some cloudy disembodied life with harps. It is about God working to reconcile all things to himself — undoing the separation between us and him, and finally the separation from the beginning of the story of the Bible — between heaven and earth.

This happens and is secured through Jesus becoming human, shedding his blood on the cross, being raised from the dead, and exalted to the heavenly throne room as the Son of God and the Son of Man — the heaven-on-earth king becoming the human-in-heaven ruler.

With this comes the idea that we are not just saved from sin, but saved for life. We are saved for life with God, and life as God’s ambassadors of reconciliation; his heaven-on-earth people; his living temple who live lives that picture and enact our hope. Not because we can bring the transformation that only God can at the end of the story, but because through our witness God delights in bringing that transformation life by life through the Gospel, and bit by bit through the parts of the earth we cultivate in our work and service to tell this story.

And this salvation — this restoration and reconciliation with God — flows out through our individual lives into our communities and the things we create together as we work, perhaps in ways that give whole nations and societies glimpses of God’s goodness. It does not always. So often Christian attempts to bring heaven to earth look more cursed than blessed, and I reckon this happens most when we embrace the violent power games of the world, rather than encountering the God we meet in the crucified Lamb so that we see God brings heaven to earth through sacrificial, reconciling love that first seeks to embrace enemies, and to cultivate life not death, as witnesses to God’s nature.

I think our outworking of this story — this Gospel — goes wrong because we are not dwelling in God’s presence; in prayer, in worship, in meditating on his word — in ways that shape our vision and then our action. And it goes right, in truly beautiful ways, when we do; when our actions in the world are grounded in our life before the throne; where our acts serving God are shaped by worshipping God as God is.

But this is our job — right — bringing heaven to earth in a tangible way as temples, or as Paul says elsewhere, ambassadors, or citizens of heaven (Philippians 3:20-21). This is where we belong in a life-defining way, and our hope is that Jesus, who dwells there, will bring transformation by his power — the power that will bring everything under control — and will also bring that transformation to our bodies so that they will be glorious like his body is glorious.

In Philippians this hope — this citizenship — produces rejoicing, even in suffering, and a life marked by gentleness (Philippians 4:4-6). It frees us from being caught up in the worries about earthly things. This is not to say our bodies will not experience anxiety or be marked by trauma, or that we should not engage earthly help for those real phenomena. But we do approach these threats, our experience of pain and suffering, the scars and wounds we bear, knowing these are not ultimate. We are not bound by those who would limit our citizenship to our bodies on earth, and seek to destroy us by breaking our minds and bodies and conforming us to their desires.

Instead, we live as those near to God; those who have access to this heavenly throne room even in the midst of our worst embodied, earthly moments. We are not prisoners. Paul, though, writes this letter when his body is physically imprisoned. Instead, in every moment, in every situation, we can enter the presence of God; enter his throne by prayer and petition. We can close our eyes to earth and open them to heaven; to the wonder we see described in these visions, presenting our requests to God, being healed and transformed by encountering him.

This, I think, is what Paul is praying for his readers in Ephesians, where we started all this — that we might comprehend, as much as is possible, that this reality is really our reality now. That it makes a difference. That comprehending this power is the basis not just of our hope for the future, but our life in the present.

This is what Paul models as he prays in Ephesians; a prayer we might pray kneeling beside Paul — perhaps physically — as those who come before God.

Paul prays that we might really see the one on the throne; that we might really know his goodness and love as we dwell here — that this is all about something beyond our imagination, but that grappling with this begins with an act of imagination; of opening our hearts to where the Bible says we are.