My denomination’s flagship old media publication, Australian Presbyterian, that is desperately trying to carve out a niche on new media platforms, has published a review of Aimee Byrd’s book. It’s fighting a losing battle because the market is already saturated with plenty of other old media platforms occupying the same digital space; plus there are all those people whose voices would otherwise be excluded from conversations in our denomination also carving out their own spaces, particularly women. It’s interesting to see an establishment media outlet taking on a woman for getting an audience and not knowing her place; while talking about how men on the internet have been behaving badly.

It’s not a good review.

Both in its take on Aimee Byrd’s book, Recovering From Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, which it says is very bad, and in its execution, ie, it’s not a “good” expression of the form, or genre, of the review.

Now, I do my own thing when I write reviews — I’m not particularly interested in assessing the review on my terms; I’m more likely to write something like a review essay – a thing of my own, inspired by the ideas gleaned from the book, and encouraging people to read (or not read) the book in question. Sometimes I write reviews of very bad books, but mostly, I write reviews of books that I think add things to significant conversations, especially conversations in the life of the church.

John Updike, who is a much more significant authority figure on the writing of reviews than I am, as both a writer and a reviewer, came up with six principles for writing book reviews. Now, these aren’t the be all and end all of book review rules; there’s a subjectivity involved in any writing. But they’re interesting principles one might use to assess whether a review is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ on some sort of scoresheet.

My rules, drawn up inwardly when l embarked on this craft, and shaped intaglio- fashion by youthful traumas at the receiving end of critical opinion, were and are:

1. Try to understand what the author wished to do, and do not blame him for not achieving what he did not attempt.

2. Give him enough direct quotation—at least one extended passage—of the book’s prose so the review’s reader can form his own impression, can get his own taste.

3. Confirm your description of the book with quotation from the book, if only phrase-long, rather than proceeding by fuzzy precis.

4. Go easy on plot summary, and do not give away the ending. (How astounded and indignant was I, when innocent, to find reviewers blabbing, and with the sublime inaccuracy of drunken lords reporting on a peasants’ revolt, all the turns of my suspenseful and surpriseful narrative! Most ironically, the only readers who approach a book as the author intends, unpolluted by pre-knowledge of the plot, are the detested reviewers themselves. And then, years later, the blessed fool who picks the volume at random from a library shelf.)

5. If the book is judged deficient, cite a successful example along the same lines, from the author’s ouevre or elsewhere. Try to understand the failure. Sure it’s his and not yours?

To these concrete five might be added a vaguer sixth, having to do with maintaining a chemical purity in the reaction between product and appraiser. Do not accept for review a book you are predisposed to dislike, or committed by friendship to like. Do not imagine yourself a caretaker of any tradition, an enforcer of any party standards, a warrior in an idealogical battle, a corrections officer of any kind. Never, never (John Aldridge, Norman Podhoretz) try to put the author ‘in his place,’ making him a pawn in a contest with other reviewers. Review the book, not the reputation. Submit to whatever spell, weak or strong, is being cast. Better to praise and share than blame and ban. The communion between reviewer and his public is based upon the presumption of certain possible joys in reading, and all our discriminations should curve toward that end.

These are good rules. Mark Powell’s review in the Australian Presbyterian breaks every one of them. Especially the ‘vaguer sixth’…

EDIT: Mark has, since my publication of this piece, suggested that he was not writing a “review” but rather a “reflection” on the events surrounding the book. Whether or not these criteria then apply is up to you (and to me, as the one posting) to discern; I’m comfortable with what I have written, but am happy for Mark’s qualifying comment to sit alongside this… I’m not sure the distinction is quite so fine as he might like, but it does speak to limitations around the word limit he was operating in; his criticisms of the book in the piece are a substantive part of the piece, and as I’ll suggest below, significantly misrepresent the book. Here are some things Mark has said on Facebook while promoting his ‘reflection’:

“Aimee Byrd’s book is deeply flawed, but there are some important lessons for us to learn as a denomination, especially regarding online civility as well as due process, around it.”

“Nathan Campbell you’ve assumed that the above article is a “review” of Aimee’s book and then judged what I’ve written in that light. However, the editor of AP asked me to NOT do another review—because so many competent ones have already been done which I mention / link in the piece—but to instead do a “reflection” on the furore around it.”

“so, here’s my thoughts on Aimee Byrd’s new book and the controversy around it…”

And when one person said “thanks Mark: an excellent review. I don’t think I need to read the book to know that it’s terrible,” he didn’t say “it’s not a review,” he said “part of the challenge here is not giving an unhelpful book undue publicity but at the same time not just dismissing it because we know we’re going to disagree. As Proverbs 26:4-5 says, this requires much wisdom.”

“What I wrote was not a formal book review, but you seem intent on questioning my motives about this. I’ll leave it for those following this thread to make up their own minds as to how successful my reflection was. As I’ve said elsewhere, this clearly has to include an engagement with what Aimee wrote.”

I think I’m hearing him correctly and disagreeing with the distinction he is making between ‘review’ and ‘reflection’ — not because I think if he were to write a more traditional ‘book review’ about the book he would take a different form, but because I think in the world of new media the text we’re asked to review includes the discussion generated by an artefact, not just the artefact itself. For Christian writers to have books published now, publishers require an online platform and the ability to produce online conversations, or buzz; I’m not sure we can separate the buzz from the book (I also made this case around a controversial review I wrote of a bad book, though, mea culpa, part of my assessment of that book was that it did not do what a book on that issue should do, and what it explicitly set out not to do, which is what I’m suggesting Mark Powell has done here).

So while Mark Powell sought to clarify afterwards, I’m not going to go through this piece and replace the word ‘review’ with ‘reflection’ — and I think even in a reflection, the criteria for reviews outlined above (and below) still stand; that we’re to be people who do not bear false witness, so it is important to as best as possible accurately present the views of those we critique; I’ve given Mark opportunity to clarify the things I’ve said about him here (beyond the ‘review’/’reflection’ thing), and edited accordingly.

As a side note — it’s conventional in this sort of writing to refer to a person by their surname alone, or their first name if you know them. I’ve known Mark Powell since I was a kid in regional NSW, but I’m choosing to use Aimee Byrd and Mark Powell in full to continue reminding you, dear reader, of the biological sex of the writer (and I say sex, not gender, because I think as a general rule we’d be better off clearly establishing the very physical givenness of sex, as opposed to ‘identity’ or ‘construction’ — I think ‘gender’ is now a confused and loaded word, especially when one starts talking about ‘manhood’ or ‘masculinity’ or ‘womanhood’ or ‘femininity’ and what appropriate expressions of those look like). Mark Powell’s review is a male, in a church context, writing about a female, in a church context, so how he writes, not just what he says, demonstrates something interesting — and that is also under ‘review’ in this review.

Mark Powell cites Andy Naselli’s review of Aimee Byrd’s book as an authoritative critique of her work; Andy Naselli comes much closer to Updike’s list of principles than Mark Powell does, but this, perhaps, is because Naselli has his own principles for public disagreement, that he drew from Tim Keller. And Mark Powell breaks those too.

1. Take full responsibility for even unwitting misrepresentation of others’ views.

2. Never attribute an opinion to your opponents that they themselves do not own.

3. Take your opponents’ views in their entirety, not selectively.

4. Represent and engage your opponents’ position in its very strongest form, not in a weak “straw man” form.

5. Seek to persuade, not antagonize—but watch your motives!

6. Remember the gospel and stick to criticizing the theology—because only God sees the heart.

I’d argue Mark Powell’s review fails on the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th principles, so he should take responsibility for misrepresenting Aimee Byrd’s views (the 1st).

The thing is; what I’m doing here — and what Mark Powell does in his review — is adopting the fallacy known as ‘arguing from authority’ or appealing to some authority figure whose views might persuade the reader of an argument if your own argument is weak; or your own authority insecure.

The problem with Mark Powell’s review is not that he doesn’t follow the principles outlined by Updike, Keller, or Naselli. It’s that it comes from an agenda never fully disclosed, and at the risk of poisoning the well, Mark Powell is not the man I would listen to on how men and women work together for the cause of the Gospel; he, in his review, assumes his theological platform is normative and Biblical, and Presbyterian, but it is a narrow sort of Presbyterianism informed by a belief in a particular theology of headship. He has principles, drawn from 1 Corinthians 11, about the hair length appropriate for women before they are being sinfully rebellious. Those views are fine for someone to hold; he draws them in good faith from a systematic theology that is integrated and coherent in its own way; but they are not the views of the Presbyterian Church, they are his views as a minister of the Presbyterian Church. Mark Powell doesn’t declare his own hand while operating as a culture warrior in his review (there are bits of Updike’s rules that are just genuinely good principles for engaging with this sort of exercise).

I think I’ve been clear enough, or at least tried, to articulate clearly how I think men and women should be working in Gospel partnership, and how that could play out differently in the courts of the Presbyterian church, and in our gatherings. It’s clear that I come from a different theological starting point to Mark Powell, and that I’m much more inclined to see Aimee Byrd’s book as, if not a necessary corrective for our churches, a good faith conversation starter from a woman who shares a confessional framework that we operate in. I say this to nail my own colours and convictions to the mast so that you can assess whether or not I break all the reviewing conventions I have laid out above…

Let’s do some reviewing of Powell’s review now.

For starters, he sets the context of the book and the discussions around it with a retelling of events in a manner that is problematic (and quite disputed); he takes a terminology (doxing) that I’m not sure he understands, and accuses Aimee Byrd of participating in doxing, when even the accusers he quotes are careful to make a distinction between Aimee Byrd sharing a site containing screenshots of the awful, slanderous, things said about her and Aimee Byrd making a site. He praises elders (men) in Aimee Byrd’s church for taking a stance against the men named in the group; without acknowledging that their names would be unknown if their fruitless deeds of darkness were not exposed; you can’t have your doxing cake and eat it too. Basically, what good Godly men do, from Powell’s view, is to be admired and defended, but women who don’t know their place are to be put back in it.

Mark Powell offers no substantive engagement with Aimee Byrd’s book-length appeal for reform in the church; instead, he misrepresents it (and doesn’t even try to re-present it fairly, he does not quote it at all). He shares the critiques of others. He never properly addresses her arguments (or landing points), in fact, he suggests she is arguing for something she explicitly says she isn’t in the book — and he doesn’t make any attempt to suggest her statements were made in bad faith and that she tried to create particular outcomes flying under the radar. He complains about Aimee Byrd trotting out feminist tropes like ‘the Yellow wallpaper’ — and, without irony, becomes an installer of yellow wallpaper. Even if Aimee Byrd is wrong on a variety of points in her book (and as a human author, whose work is not infallible, this is likely), this is not a good faith exercise in dialogue to persuade Aimee Byrd of her errors; it’s an attempt to stop people encountering her arguments. It is a hatchet job. Even if Aimee Byrd is wrong about everything — the point of Updike and Keller’s principles — is that you treat your neighbour as you would like to be treated; if Mark Powell’s view on women is that we shouldn’t listen to them in case they teach us something, then his review demonstrates the folly of that approach (this, I don’t think, is Mark Powell’s view on women, but in demonstrably failing to listen to a woman who has published a book that he has set out to publicly review, this is what Mark Powell demonstrates his actual view on women is). I believe Mark Powell loves women, and wants to see them flourish; I believe his writing is thoroughly consistent with his framework and how he believes the Bible spells out a pattern for human flourishing. I also believe Mark Powell’s framework is wrong, and while I think he is a Presbyterian, and our denomination is one where big R Reformed people with sympathies for the Federal Vision movement, or those who like Doug Wilson, might find a home, I don’t think our denomination is so narrow that only those with this sort of framework should find a home (or a platform). The AP mag has form on this; it was, of course, home to the article that suggested women’s ministry training should be restricted to mothercraft.

In his framing of the debate Mark Powell makes a category error; a sort of error quite common in hard complementarianism. He jumps from a passage where Peter is explicitly talking about the relationship between husband and wives to make a case for how ‘all men’ and ‘all women’ should relate in obedience to Scripture.

“We should clearly and consistently condemn any physical or verbal abuse of another person, and especially when a man commits this against a woman. 1 Peter 3:7—a passage that Byrd strangely never refers too in her book—is more than apt.

“Husbands, in the same way be considerate as you live with your wives, and treat them with respect as the weaker partner and as heirs with you of the gracious gift of life, so that nothing will hinder your prayers.””

Now, unless Mark has substantially changed his position on 1 Corinthians 11 since last we debated it; he and I read that chapter differently too — I think veils (head coverings) were a first century wedding ring — a picture of the inter-dependence of husband and wife — and that wives in Corinth were declaring independence from their husbands in public by unveiling their heads (a greek word for wife is the same as a greek word for woman, and context shapes how we read it). It’s an approach that has significant implications for how we structure not just church and marriage life, but all relationships between men and women; and that Mark Powell is so quick to use them interchangeably here is at least indicative of a consistency in his approach…

So far as I can tell as an outsider to the life of the Byrd household, Aimee Byrd writes with the full support of her husband. Some of the worst examples of comments on the cesspit, The Geneva Commons, were comments speculating about their relationship and asking “where her husband is” as she writes the things she writes. The issue with the comments on the Geneva Commons, misogynist though they are, is not an issue simply because Aimee Byrd is a woman and the people making the comments are men (though that fits with Aimee Byrd’s call for reforms too), the issue is that Aimee Byrd is a human being made in the Image of God, being transformed by God’s Spirit into the image of Jesus; how we treat her is an expression of our view of Jesus (‘by this shall all men know that you are my disciples, that you have love, one for another’). The way we treat our brothers and sisters in the faith (including the way I write about Mark Powell, who I do see as a brother in the faith, just one doing substantial damage to the witness of the Gospel in Australia by playing the culture war game so vigorously both inside and outside the church) reveals how we see Jesus. If Mark Powell can’t bring himself to listen properly to Aimee Byrd’s cries for reform — cries echoed by women in our own churches here in Australia — even if he disagrees; then this review is an indictment of him (and perhaps the platform he is given), not of Aimee Byrd.

His review is a staggering effort to eradicate the voice of a woman, while, at the same time, it is being revealed the length a group of men in positions of authority in a sister church in the U.S were going to to also eradicate her voice. And Aimee Byrd is not a feminist outsider, she’s not even an egalitarian — she is a member in good standing of a Presbyterian Church, a church in good standing with the Presbyterian Church of Australia; how we respond to her is going to communicate volumes to the women in our churches.

Mark’s review is not the same as the comments on the Geneva Commons; I’m not wanting to suggest there’s an equivalence here; but it’s easy for women in our churches (I hope) to see the Geneva Commons experience as an outlier, rightly condemned, than a norm, if the norm isn’t a similar eradication of women’s voices on how our church is structured (and even, how we understand the Bible). Mark Powell was right to unequivocally condemn the Geneva Commons threads; but to condemn that while ‘reviewing’ the book in such a bad faith way (see Keller’s rules, and Updikes), is to be complicit in the same ‘yellow wallpaper’ — just not to the same toxic degree. He says:

How Aimee Byrd has been treated clearly grieves the Holy Spirit (Eph. 4:29-32). And the fact that many of the men who are guilty of such sins are office bearers in Christ’s church is a timely warning and exhortation for us all to repent and refrain from any such conduct.

I believe that while his treatment of Aimee Byrd in this review is not the same as the treatment dished out in the Geneva Commons, that perhaps benevolent patriarchy is still patriarchy; and maybe it’s a more damaging expression of that in the long term because I don’t think the Geneva Commons guys are going to get their views platformed in our denomination’s national magazine.

Let me quote another para of Mark Powell’s review. Where he gets into his substantial criticism of her book (points largely echoed in the two other reviews he cites).

“Byrd does a very poor job in handling the Scriptures. Significantly, passages which are integral to the entire debate are completely ignored (i.e. 1 Tim. 2:8-15, 1 Pet. 3:1-7). This is inexcusable, especially when Byrd is arguing that women should take up teaching and leadership roles in the church and that obscure New Testament figures such Phoebe, Lydia and Junia were “church planters” and even apostles.”

Mark Powell does not demonstrate this assertion; he simply asserts it — and maybe he’ll appeal to word limits and the importance of getting his take on Aimee Byrd’s book out there to stop it gaining a foothold in the Presbyterian Church of Australia. His main contention in this paragraph seems to be not so much that she mishandles the Scriptures, with reference to Phoebe, Lydia, and Junia — but that she ignores the Scriptures Mark Powell thinks she should be writing about.

This is Mark Powell complaining that the book does not talk about elephants, when, in fact, it is not a book about elephants at all. Mark is reviewing the book negatively for failing to meet his terms. He misrepresents Aimee Byrd as trying to do something (arguing that women should take up teaching and leadership roles in the church) that Aimee Byrd explicitly says is not her intent. Mark Powell is consistently black and white in his thinking, and does like to put things through a pre-conceived grid while assessing them; Aimee Byrd seems to me, in my reading of her book, to be trying to suggest the grid and the black and whiteness aren’t the be all and end all of relationships between men and women in the church, and that the grid of asking about ‘roles’ and ‘authority’ accounts for 1% of our life together as Christians, and she’s interested in exploring what to do with the other 99%…

He complains that the book is weak in precisely the area the book says it is not addressing. Now, if he wanted to say this book was a Trojan horse that undermines the structures of the 1%, he could’ve just said that.

Mark Powell says:

“Byrd’s treatment of Genesis 1-3 is superficial at best. She argues that there is no creation paradigm involving authority and submission between Adam and Eve. That is patently untrue.”

I’ll just put this here.

“Interestingly, Adam was called to a special submission in three areas. Before the fall, Adam and Eve served in a holy temple-garden. Adam bore a priestly responsibility of the vocation to guard or protect, which is the meaning of the word keep in this text: “Then the LORD God took the man and put him into the garden of Eden to cultivate it and keep it” (Gen. 2:15 NASB). Adam was called to submit, or sacrifice himself, in this way. Second, Adam had to sacrifice a piece of his own body for the creation of Eve (Gen. 2:21–22). And third, even in describing the union of marriage, we see that unlike the surrounding ancient patriarchal culture of the time when Moses wrote Genesis, in which the woman left her family and was then under the authority of her husband’s family, the man was to leave his family and cleave to his wife (Gen. 2:24). So if we want to call this leadership, yes, it is the best kind. But it is also submission—sacrifice of the man’s own rights and body for the protection of the temple and home and out of love for his wife. These are proleptic representations of Christ, the true keeper of our souls (see Ps. 121), who left his heavenly home, took on flesh, lived the life that we could not, and died the death that we could not so that he can hold fast to his own bride, the church.” — Aimee Byrd, Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 116-117

This ‘superficial reading’ is consistent with, for example, Greg Beale’s ‘Eden, the Temple, and the Church’s Mission‘ — it’s an expression of good, Reformed, Biblical studies work on Genesis 2, drawing out implications for how we understand the pre-fall partnership between man and woman. Aimee Byrd doesn’t just have a ‘creation paradigm’ for Genesis 2, she has a Gospel paradigm. What Mark Powell means by ‘superficial’ is ‘does not agree with my reading of the text’… And that’s fine. He should just say that.

Mark says:

“Byrd argues for what I refer to as a “sexist hermeneutic”. Byrd believes that Scripture is inherently ‘androcentric’ (male-centred) and that we should adopt a “Gynocentric (feminine) Reading of Scripture”. This is an expression that Byrd uses no less than twenty-three times. Her point is that while women are not the centre of the Bible’s message, the feminine perspective should be one of the grids through which we interpret it. The problem with this approach is that it de-thrones Christ from being the lens through which we interpret God’s Word (e.g. Luke 24:27).”

Aimee Byrd does indeed see Jesus as the lens through which we interpret God’s word; Mark Powell misrepresents her at this point; I believe that Jesus is the objective fulfilment of Scripture, it is written about him, but that doesn’t stop me reading Scripture from a cultural position, in a language removed from the culture and language of the first audience of Scripture. I have to attempt to put myself in the headspace of others to humbly see how Scripture might be fulfilled in Jesus because I am a limited creature, and cannot escape my own subjectivity. My sense of Jesus being the fulfilment of Scripture is aided when I hear the perspectives of others with different cultures and experiences; Aimee Byrd seems to me to be arguing that by hearing the voices of women as they subjectively interpret Scripture from their own creatureliness, we might enrich our understanding of how it is fulfilled in Jesus (something demonstrated, I think, in her treatment of Genesis 2 above). Creatureliness is not a sin — and we can’t insist that a woman read and notice things about Scripture through the eyes and perspective of men — as though ours is the objective experience, or as though we have perfect access to truth, without eradicating their creatureliness and the difference we want to keep affirming. To do so is the opposite of humility. Aimee Byrd isn’t advocating for men not reading the Bible as men, she’s advocating for co-operation in our sitting under the text and looking to find its fulfilment in Jesus. Mark Powell is arguing for the sort of colour-blind, experience blind, black and white approach to truth that again, is thoroughly consistent with the sort of modernism and politics he finds himself drawn to (arguably because of his own creaturely distinctives). An example from my own life and preaching might be a helpful one here — you will, as a man, preach the story of David and Bathsheba, or Absalom and Tamar, differently if you ask women what these stories make them feel and how they’d like to hear them taught. David’s primary failure is not that he ‘betrays his comrade in arms Uriah because Bathsheba belongs to him’ (as I’ve heard it preached). Bathsheba is not a temptress (she’s washing herself according to the requirements of the law). Our perspective on the events of this narrative are limited, and our limitations will affect how we see a story fulfilled in Jesus (that he is not a king who treats women as objects to be ‘taken’ by strength like Eve ‘took’ the fruit she saw and desired).

We, the church, will be richer and have a truer picture of the Gospel of Jesus, if we listen to those given ‘the same Spirit’ who are part of the same body — this is not to jump straight to questions of teaching and preaching in the gathered church, there are a whole lot more options for listening (like, you know, reading books written by a woman, that call for reform, and trying to hear them properly). Aimee Byrd describes the #MeToo movement, for example, as a gynocentric movement — a movement where women are sharing about their experiences of life in society, and the church, from their creaturely perspective — movements like this are a chance to affirm difference, but to be enriched by difference as well.

“This movement is a gynocentric interruption. Women are using their voices and asking men to listen. How is the church going to respond? We certainly don’t want to mimic the culture and adapt the philosophy of the sexual revolution. But in our efforts to combat the reductive worldview of our secular culture, we need to make sure we are not overcorrecting by slapping yellow wallpaper over it. We need to look at our own blind spots and embrace the whole picture given to us in God’s Word.” — Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 93

“We have the privilege of listening from the perspective of the full revelation of the gospel. What do we have to say to our culture now about the holiness and grace of our Lord God? What do we have to say about the value of men and women made in his image? What do we have to say about his household? We live in a time where we can cruise over to Walmart and buy a Bible for $5.99. Now that we are armed with a better idea of how the male and female voices operate synergetically in Scripture, let’s explore Christ’s presence in the Word of God and therefore its relationship to the church.” — Aimee Byrd, Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 94

Sadly this review is an example of the very yellow wallpaper that Mark Powell found so triggering. He says:

“Byrd contends that complementarians are “biblicists” who “emphasize proof texting over a comprehensive biblical theology” and that “they often don’t notice they are also looking through their own lens of preconceived theological assumptions”. Ironically, though, this is what Byrd herself is guilty of doing. Her entire book is framed by the classic feminist metaphor of peeling back the “yellow wallpaper”. And as such, it is her own philosophical feminism which wallpapers over the meaning of the Biblical text.”

I think the quotes I’ve included above already demonstrate a Christ-centred, comprehensive, Biblical theology and even theological anthropology, at the heart of Aimee Byrd’s work. The issue is not that she doesn’t cite passages from the Bible, or have a theological framework — and the issue certainly isn’t the yellow wallpaper metaphor that Mark Powell seems to have misunderstood (which is about the normalisation of the eradication of women’s voices), it’s that Mark Powell doesn’t acknowledge that his own theological system sees women’s voices seeking to ‘teach’ men something as problematic, and so he was never going to be able to listen to Aimee Byrd on her terms.

What we have here, in Mark Powell’s review, is a perfect artefact of approaching a book through his own lens of preconceived theological assumptions. He asserts, without demonstrating, he dismisses, without engaging, he silences, without listening. The reason he can’t see the yellow wallpaper is because he is the yellow wallpaper.

He reads Aimee Byrd’s book through his grid — which is a grid emphasising headship; specifically male headship. A view that ends up centred on the question of authority, and the role of an individual in authority. I’m not going to prosecute the Trinity question around eternal subordination, or functional subordination, or whether the father has authority over the Son and Spirit, and what that does to questions of equality; I just think that’s a weird, western, modernist (and, frankly, worldly or ‘Babylonian’) grid to read back into the relationships in the Trinity. The Trinity as a community is dynamic and relational; the Son submits to the Father, he does not grasp equality with God, while the Father ‘exalts the Son’ and raises him to the ‘highest place’ giving him the name ‘above all names’ — this sort of static authority structure where we’re worried about what individual is ultimately ‘the authority’ is such a weird way to approach human relationships even if you are trying to map them out according to the Trinity. One thing the Trinity should challenge, and so too our union with Christ as ‘one body,’ is our radical, western, notion of individuality, that freights questions of authority with much more weight than they should carry. Aimee Byrd seems to Mark Powell to be undermining authority structures precisely because he has no category for the sort of thick co-operation or even complementarity that Aimee Byrd is calling for. Her vision of the church is not one without male leadership (she affirms the structures of her tradition); it’s one of collaboration and partnership; of listening.

We can even back it up a bit. Do you have only men handing out bulletins, helping visitors to find a seat, and passing the offering basket? Why? What message might that be sending? If Phoebe can deliver the epistle to the Romans, a sister should be able to handle delivering an offering basket. Backing it up a little more, are laypeople teaching adult Sunday school in your church? If so, are both laymen and laywomen being equipped to do that? If Junia can be sent as an apostle with Andronicus to establish churches throughout Rome, then you should at least value coeducational teaching teams in Sunday school. Do the men in your church learn from the women’s theological contributions? If the Cappadocian father Gregory of Nyssa can call Macrina “the Teacher,” showing just how dependent his theological understanding of the Scriptures was on his sister, then the men in your church can learn from their sisters as well. Sisters make great adult Sunday school teachers when invested in well, as well as excellent contributors in class discussion as learners. They could also contribute theologically in written resources the church offers. And helpful women authors should be recommended as church resources. Like Macrina, they may even excel in training other theological leaders. That should all be seen in the dynamics of a typical Sunday in your church, whether you hold to male-only ordination or not—men and women co-laborers serving under the fruit of the ministry with reciprocal voices and dynamic exchange.”— Aimee Byrd, Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 233.

Note, for example, Aimee Byrd doesn’t call Junia a ‘church planter’ — but a sent one (an apostle) who partners with Andronicus to establish churches; she isn’t creating a separate category of female ordination and leadership — she’s calling for collaboration — for being co-laborers. She’s not calling, so far as I can tell, for any woman operating under her own individual authority, but for a recognition of genuine inter-dependence and partnership. This is Aimee Byrd’s ‘trojan horse’ — her ‘gender agenda’ — that we, the church, might partner together in love to make the truths of the Gospel; that together we might be pursuing the example and image of Jesus in our lives, expressed in our relationships.

“Just think of the way Jesus showcases leadership in the washing of feet and how differently he exercises his own authority as the Son of God, in contrast to the one-dimensional ways taught in biblical manhood. He doesn’t play the man card, or even the Son of God card! He serves. He listens. He teaches. He fulfills. He gives his whole self. He equips and empowers men and women. And he calls them to do his work. He does not call them to different roles or different virtues.” — Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood, 123.

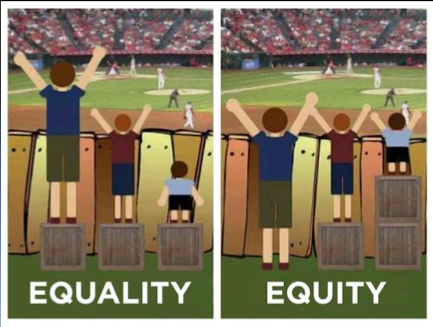

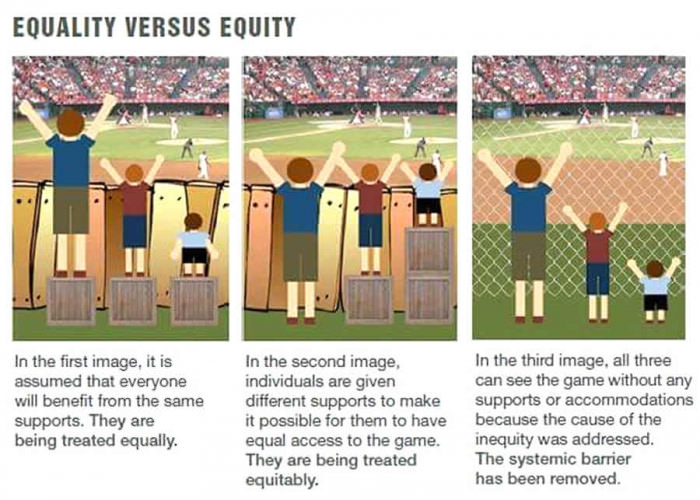

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As

Egalitarianism — the equality of men and women — is the world’s naive, or optimistic, solution to the problem of cursed life in the world; it’s a solution that comes without truly understanding that the problem is that life in the world is cursed, and that we can’t fix the curse ourselves just by pretending it isn’t there. It recognises a truth about our equality in dignity and value, and is less likely to accept the parameters offered to us by curse and sin. But it often settles for equality or equity as solutions, and doesn’t totally acknowledge that our difference is real, and that sin and curse have exaggerated the impact of that difference. It is an attempt to respond to a broken world by creating a new one (and in some sense, it does look forward to the new creation, but perhaps optimistically over-realises that picture in this world). So for Christians to adopt it just strikes me as missing the heart of the diagnosis, and the solution, that come with our story. As