This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

You can’t believe everything you read on the Internet. In July, rumours of the death of former U.S. President Jimmy Carter circulated, leading to an outpouring of grief for the 99 year old some months before his actual death. Carter was an interesting guy if you watch the horror show that is U.S. politics; he seems to be universally loved — and one of the reasons he was loved, was because of his work with the charity he helped make famous, Habitat for Humanity — it is a charity that builds houses — habitats — for humans.

It exists in Australia as well — and it is built from the recognition that we need a home; a habitat to survive and thrive, as we inhabit time and space. The spaces and places we call home — their rhythms and rituals, the furniture and the people who fill them — form us.

Back in week one of this series we were in Athens and we imagined the shift facing Damaris and Dionysius — these two people who believed the Gospel (Acts 17:34) — from the architecture of Athens and its idols to the rhythms we saw in our reading from the start of the church — both the rhythms of meeting together with other Christians — a new household — and of meeting in a very different sort of sacred space — the home (Acts 2:46–47).

This is the architecture described in the New Testament as the first habitat for this new community, the church, which we saw last week is called the household of God; a kinship network that teaches us how to be human — the church and our households within it — as we wisely build our lives — and we saw the way the New Testament uses the metaphor of building a house for this process.

The physical spaces we live in, where we meet together and eat together, structure our lives. And to live in the household of God means changing the furniture — these structures — the architecture of our lives as our habits change.

And so I wonder, first up — if you think about your house — what are your physical spaces geared towards; what are they producing in you? What about your workspace or other places you spend time habitually — what about church?

What are the rhythms and rituals in your habitat? Who lives in your habitat with you?

What changes can we make to our habitats to become the humans God is inviting us to be in his household — and so we offer the hospitality and transformation of his household to others drawn in to this ecosystem?

How is your home shaping you?

I want to acknowledge up front that many of us are living in non-ideal situations; not where we imagine for ourselves, and we are already at the limits of what we can afford in the current economy — interesting if you remember last week that is a household word — we are finding the household management of the world pretty unbearable.

And so what I am not saying is move — change in ways we cannot afford; but maybe there are changes to how we live in our spaces — whether at home or in shared spaces that we cannot afford not to make — especially because we will see this idea as we explore our two readings is about both our habits and who we are habitually connected with.

Anyway. Here is a tour of our house — I took these photos when there were dogs around, but fewer humans than normal — and this is not me saying our house was well designed to form us — it was a mix. The photos are our house as it was — since preaching this series we moved out and conducted significant renovations.

When you walked through our front door there was a hallway, and on the wall there were pictures our kids have made hung on a string.

On the left of the hallway were our bedrooms — there were three of them for five of us — we added another bedroom to minimise fights between the residents who share — the kid ones — and to provide a little more space away from each other — I will not show you pictures of the bedrooms both because they are pretty much just bedrooms, and because of privacy and mess.

Bedrooms are for sleeping — although there is a desk in our room, and bedside tables covered in books, that are also where we charge our devices. Which means they are on hand as we go to bed or wake up in the morning.

Our living area is open plan — we like this because it means we can see what our kids are up to. We built these desks into this set of shelves so kids would work there and not take screens into their rooms.

We really love our kitchen where there is a big communal island bench, where multiple people can prep food together — and breakfast bar — there is a fruit bowl in the middle to encourage us all to eat fruit, and some flowers because they are beautiful, and mess because we are a family and both parents are working pretty much full-time jobs and we still had not cleaned up fully from Growth Group a couple of nights before.

There is the coffee machine that keeps me sane — one that is great for firing up to make coffees for more than one person at a time.

A dining table in the corner crowded in by the dog crates — and our couches, which are both pointed at the TV so that when we collapse onto them once the kids are in bed we are inevitably drawn in to the screen.

The next biggest thing on our wall is the clock — well, it is maybe the painting — but in the morning we are ruled by the clock; racing against time to get everyone out the door in chaos.

Out the back we have got another table — with more clothes and toys — and a pizza oven in the corner so we can have people round, and play equipment for the kids because we want them to be habitually active.

This is the habitat shaping our household — it is built for chaos and hospitality — filled with marks of conflict, and mess, connection and distraction — and there are good and deliberate bits built around eating together and being together, but other bits that rule us more than they should; the screens on our wall and on our bedside table — part of thinking through our architecture means curating what is on our screens; and where our screens are — both the TV screen and all the stuff you are paying for to stream distraction into your life, and the stuff on your phone and in your browser.

What does your habitat look like? Are there ways you have set it up to make certain practices repeatable and easy? As an expression of your values — or just as something shaping them by shaping your habits?

Most of us spend lots of waking hours at work — like I said last week, my workspace tends to be my couch — or the desk in our room — or the dining table — when I am not working from a café or meeting people — but I used to work in a cubicle, and so I wonder how your workspace is set up…

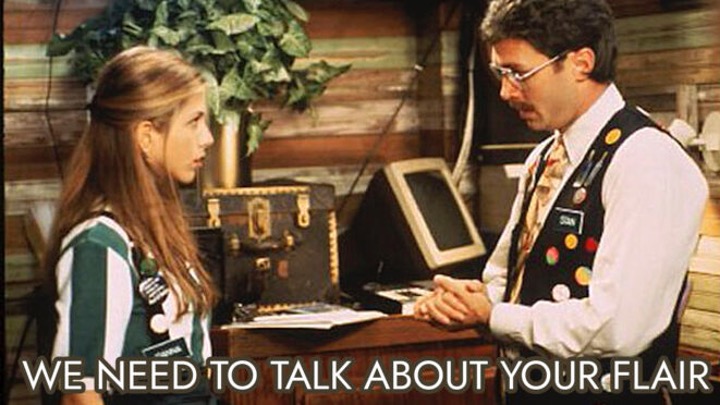

Maybe you have a cubicle — what pieces of “flair” — the idea made famous by Office Space — is expressing your personality but perhaps even drawing your eye and prompting your thoughts when you have a moment in your cubicle? What is on your screen?

What your space looks like is going to vary widely based on what sort of job you do — you could drive heaps where your only real decision is what you listen to on the road, or if you hang something from your mirror that reminds you to pray, or something like you will often find in a car driven by someone whose religion involves more icons or images.

How have you structured things to aid your work? Or your formation? Some of this is silly window dressing, but changing our habitats can shape the way we work. Carpenters in their workshops use these things called jigs — deliberate structures they will turn to for repeated tasks that make them faster and more automatic.

The author Matthew Crawford is a motorbike mechanic and philosopher — he is all about keeping our heads and our bodies connected. He reckons we could all learn from carpenters and have jigs that produce the repeated habits we want to see more effortlessly; where our habitat assists us automating our habits. He defines a jig as:

“A device or procedure that guides a repeated action by constraining the environment in such a way as to make the action go smoothly, the same each time, without having to think about it…”

— Matthew Crawford, The World Beyond Your Head

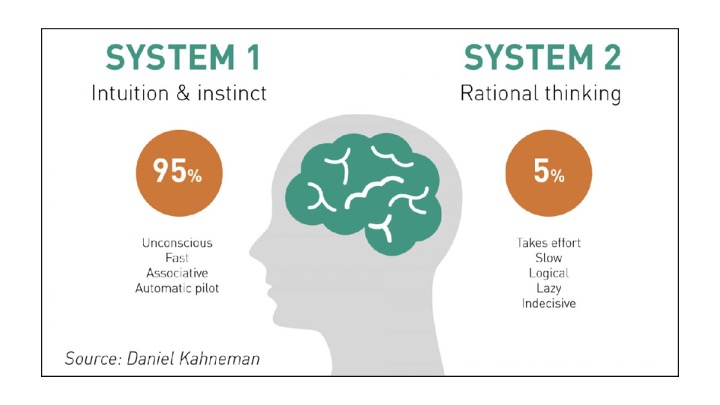

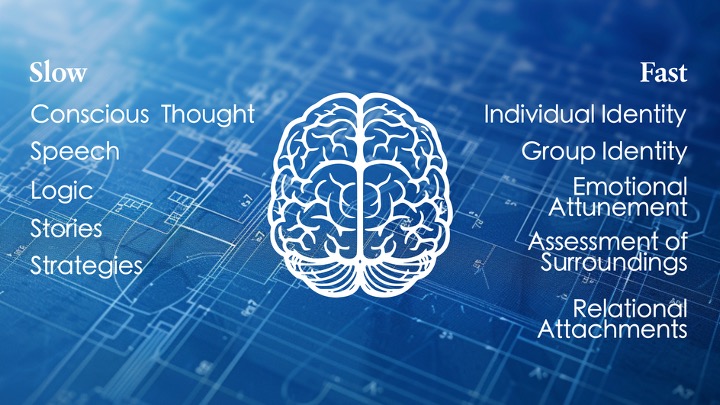

This fits with the brain science we have been looking at a bit this series; the idea that we think about things in one part of our brain, but have this automatic set of processes on the other — one of the guys who made this brain-system thing popular, Daniel Kahneman, says we form the fast side of the brain the way we learn skills with our body — through repetition; habit — and the best way to fast-track that is to set up our environment — our habitat — to produce the behaviours we want to repeat.

“The acquisition of skills requires a regular environment, an adequate opportunity to practice, and rapid and unequivocal feedback about the correctness of thoughts and actions.” — Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast and Slow

We will find these jigs — this environmental organisation — working to form us in ways we do not notice in stuff designed to addict us, to automate harmful behaviours — and in things like weight machines at gyms as opposed to free weights that guide our motions along a repeated path to help us develop a muscle.

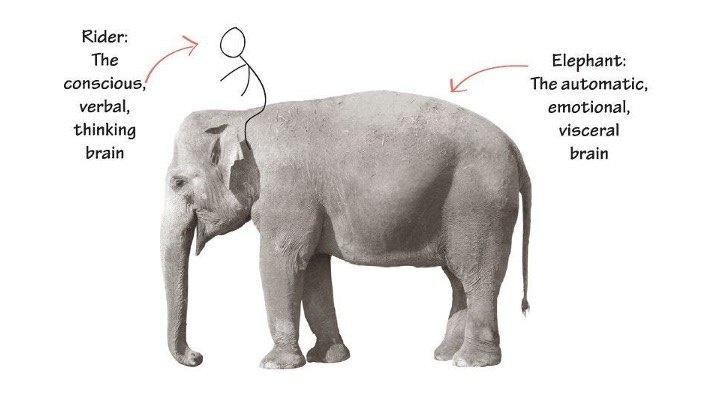

So what about this habitat? Where we repeatedly come together — habitually — how are we being shaped as we walk through these doors and sit in rows — learning not to look at each other eye to eye, which we saw last week is super important — but to stare at and listen to people up the front — and some of that is feeding into the slow-process part of our brain — the rider of the elephant — and this is important. The rider’s job is to steer things around and decide what skills to develop and how to do that — we focus on hearing from God’s word; and we participate in habits with our bodies — standing and sitting to sing; engaging in prayer, sharing communion — breaking bread together up here, and then eating together downstairs.

But what are our jigs? The structures that guide our actions in church life? The pews… the pulpit… the communion table… the baptismal pool… the coffee machine… the tables where we eat together downstairs?

The architecture of this space works to produce behaviours that we repeat that work to produce us.

I wonder how this architecture could shift — or how we could think of our movements through this space — so we are working not just on knowledge but on attachment and joy and skill development — learning the skills of loving others intuitively because we love God intuitively; because we have learned that intuition through practice.

And who are we gathering with? Who are the people forming our habitat? Our household?

If we want our habitats to be jigs that help us learn a skill; set up to make repetitive right action shape us, we want to make sure both the context and the content of what we are trying to form in ourselves — who we are trying to be, with a picture of how we are going to get there — like a trainee carpenter — an apprentice in a workshop, or someone working out in a gym — it helps to have teachers around too. Examples who are part of the furniture; the habitat, and who are teaching us and correcting us as we practice our humanity.

I reckon that is what we see in Acts, as these believers whose hearts are being reformed to be directed to God are devoting themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to time with God in prayer while eating together in houses in this new community. And in Hebrews, the writer is building on this idea that we are located in God’s house now — behind the curtain in the Temple, as we saw last series — we are living in holy space; this is our habitat (Hebrews 10:19–20). We have Jesus as our holy personal trainer; the master builder who is the priestly head of the household of God (Hebrews 10:21), and we are caught up in this exercise of coming to God (Hebrews 10:22) — this is the practice that will shape us most, knowing our hearts have been cleansed; our sins have been forgiven through the blood of Jesus, and we have been cleansed so we can come close to God — and the writer of Hebrews pivots from this to say “OK — the goal is drawing near to God” to the call to “hold unswervingly” to this hope. This is an active thing — a directed thing — “hold this hope” (Hebrews 10:23). This is a practice. Practice hoping because God is faithful.

Our habitat should be jigged up to teach us this skill of hoping; knowing that God is faithful to his promises — and what else? To ‘love and good deeds’ — we spur one another on — encourage one another towards practices that shape us as God’s children. “Love and good deeds” — the stuff Jesus taught and calls us to practice (Hebrews 10:24).

And how do we do this? We stay in the habit of meeting together (Hebrews 10:25); we habitually enter habitats that will shape us in a certain way in our practice of meeting and our practices together — especially the practice of encouraging one another. And why — well — because of where we are going — towards this Day. Now. I almost stopped here. This would have been an easy thing to apply, and to talk about — but the passage keeps going. Verse 26. It is a doozy. I reckon the hardest verse in the New Testament to balance against our understanding of the Gospel.

“If we deliberately keep on sinning after we have received the knowledge of the truth, no sacrifice for sins is left, but only a fearful expectation of judgment and of raging fire that will consume the enemies of God.” — Hebrews 10:26.

It is a warning to persevere — to keep building wisely rather than turning away from the foundation that is Jesus; those who are saved will be those who stick at it, those who do not stick with Jesus will — the foolish builders — well, the storm that will hit and test our house is not just suffering in this world — it is the testing of God’s judgment. This feels weird coming hot on the heels of a claim that we should come to God with full assurance…

But this is a theme the writer of Hebrews has banged on about all the way through the letter; the way to have assurance that you are part of God’s family (Hebrews 3:16), his household, is if you are hanging on to hope that God will be faithful, because Jesus is faithful, and we have just read about the practices that will keep you there — the practice of sinning, rejecting Jesus, will stop you being faithful to Jesus (Hebrews 10:29). I do not know about you, but I can forget that hope, or feel it slipping in moments when I turn to sin — and that is a pathway that leads to bad places.

There is a particular warning here against finding life in Jesus; building on him, and then deliberately, habitually, rejecting him and turning away. To do this would leave us especially deserving of punishment — knowing the holiness of God and treading him through the dirt. The writer of this letter is making a pretty strong case to choose life and joy and God’s love in the face of this Day, rather than the alternative. And the point of this rhetorical move, like in Deuteronomy in the Old Testament, is to choose life, not death; blessing, not curse; and to build habits that will prepare you for that Day so that you can endure all the other days between now and then (Hebrews 10:32) — and any conflict or suffering — as people of joy and hope — connected; not alone. In The Other Half of Church the authors talk about that connected joy we looked at last week, where we are together with people who are glad to be with us — reflecting God’s delight to be with us — being vital for growth — it is also vital for surviving suffering.

“Our identity is built and formed by joy-bonded relationships. The identity center in our brain grows in response to joy.”

— The Other Half of Church

It protects us from trauma; which they reckon happens when we suffer alone; without joyful security and people to process with.

“Suffering turns into trauma when we are unable to process our suffering with God and other people.”

— The Other Half of Church

The writer of Hebrews does not want people suffering alone; or suffering without having habitually built the relationships that might protect you from traumatic harm. They say “remember how just after you trusted Jesus you endured suffering” (Hebrews 10:32); being publicly insulted, persecuted… being side-by-side with those suffering and being persecuted (Hebrews 10:33) — suffering with those in prison — hoping together (Hebrews 10:34). This is a picture of occupying a household together; a habitat — they even had property confiscated and stayed joyful because their true home is in God’s presence… and holding on to our hope; our confidence — persevering — habitually — leads to being home with God.

Drawing near to God.

Holding on to and professing their hope.

Spurring one another on toward love and good deeds.

Meeting together habitually.

Encouraging one another.

You imagine they are doing what the Acts 2 church did too — praying. Studying the teaching of the apostles; the Gospel. Breaking bread — communion and eating together — in houses. Learning by heart the skill of hope and perseverance and joyful connection to God and each other.

Our habitats matter — who we fill them with matters — because our habits matter; cultivating habits of perseverance in faith and hope; drawing near to God through Jesus is how we exercise our faith and how we are formed; how we hold on to rather than throwing away Jesus (Hebrews 10:35). This is what persevering looks like; and persevering is what forms us as we draw near to God (Hebrews 10:36).

We are formed in this habitat for our new humanity; as we learn skills by heart; as we automate this perseverance by habit. And we form habits — getting in the groove of godliness — by structuring our environments and repeating our actions in loving environments. So it becomes easier to repeat right actions than wrong ones, and so we limit our freedoms to choose badly.

We will find these jigs — this environmental organisation — working to form us in ways we do not notice in stuff designed to addict us, to automate harmful behaviours — and in things like weight machines at gyms as opposed to free weights that guide our motions along a repeated path to help us develop a muscle.

This might mean keeping your phone out of your bedroom — or screens away from places where you know you are likely to engage in bad habits when nobody is around — it might mean turning couches towards each other, or eating at the table, or all sorts of things — it might mean reaching for God’s word in the morning, whether that is in a physical Bible or an app, before you reach for or hook into an algorithm; it might mean not being ruled by the clock — it might mean adjusting how you redeem the time in your car or your cubicle or the little visual prompts you use that remind you who you are at work, where things get stressful…

It might mean changing how we approach church so it is not just a place where we sit and look forwards and hear one or two people speak, but a community where we gather together to look at one another and direct each other’s gaze to the throne room; encouraging one another.

People are part of our habitat — perhaps the most important furniture in our lives — so tweaking our environment involves making sure we are connected to God’s household in a real way — that joyful and connected way we talked about last week — and this is not just about meeting together where safety and joy are the end point; those things are the soil that enables transformation when we encourage one another towards our goal; our hope.

This also means choosing not to meet together with God’s people is a choice to be formed by a different habitat — to not be encouraged by God’s people, or to encourage God’s people as we do this for one another. To risk not persevering.

So what is this encouragement thing — really — I reckon sometimes it is the “keep going” idea — where we suffer together and say “keep going,” “hold on,” “remember the destination”… stay faithful… prodding each other towards perseverance… holding on to the hope we profess — but part of this will be about calling folks back to holding on. Back to hoping. Back towards love and good deeds; towards being and becoming the sort of people Jesus calls us to be (Hebrews 10:25).

I reckon we are comfortable working at being a joyful and connected community — even with eye contact (which we “practised” at communion and in singing together the previous week) — one where we want people to be included and feel safe and maybe hear some good stuff or sing some good stuff to each other — I am sure we can get better and better at noticing the good things people do as part of cultivating joy and gratitude — being glad to be together — but I reckon some of this encouragement stuff is actually about saying hard things to one another — calling one another back to being who we are meant to be — and our habitat needs the sort of people who teach us skills by telling us when we get things wrong — and by showing us how to be who we are learning to be.

I am not sure we always have the relational security or the joyful attachment we need for that sort of speech to happen well — and then I am not sure we have practised this encouragement and spurring one another on when the pressure is not on, so that we are able to do it when it is real…

After joy and hesed, this is one of the practices suggested in The Other Half of Church for forming this side of our brain; forming our character. The authors talk about building a habitat of relationships in terms of forming group identity and calling each other to live together in this community — now — the book warns about how this can go wrong in cults and abusive contexts, we should not be naïve about this — but I reckon those of us who have experienced abuse and trauma — abuses of power or authority — can respond by rejecting all authority and just trying to do our own thing — which is another way of being formed but one that leaves us alone, or just with peers, or people we have got authority over like our own kids, or people we are teaching in various contexts.

I know I have struggled to work out what authority is and even if it can be used well, without harming others. I have found this part of my job the most difficult bit; because I recognise the harm done to so many of us through bad authority, and I do not want to compound that, but this fear — driven by love — pushes me — and others — away from hard and necessary conversations.

This is not who we are invited to be for each other. It is not who we say we are for each other. One of the values of our church is that we speak truth in love to one another in vulnerability and honesty. This love bit involves that security and joy — but this speech bit can be hard. Scary.

“We are vulnerable and honest about our own sin and brokenness, living and speaking the truth to one another in love, and welcoming to those not yet trusting Jesus.” — City South Presbyterian, Mission, Vision, Values

And while there might be a role for spiritual parents or those in authority to have these conversations, this is a one-another job — we are to spur one another on as we meet together — and the authority we are trying to point to is Jesus’ authority, not our own; we are part of his household, not our families of origin or our ideal communities, and so this sort of conversation involves discernment.

Anyway — the book talks about how important it is not just to talk about beliefs but about values; the sort of people we are and who we want to be, not just what we think — and about the need to proclaim these values habitually.

“One way a community can build a strong character identity is by speaking regularly to each other about what kind of people we are.” — The Other Half of Church

They say some traditions recite doctrinal statements — like we do with the creed — but we have also got to learn the vocabulary for how we live; our shared values — the commands of Jesus — so that when we are not being consistent we have a framework we can use to call people back to love and good deeds.

“Some traditions recite doctrinal statements as part of their Christian practice. We also need to do the same with how we live. We need constant reminders.”

— The Other Half of Church

This kind of correction is hard because it involves shame, inevitably — when we are told we are doing something wrong — but when there is genuine love and joyful connection, shame does not threaten our relationship or isolate us, knowing we are loved and secure helps us regulate that shame response and direct it towards growth — when this speech is genuinely encouraging it spurs us not just away from wrong action, but towards a correct path.

“Without hesed, shame will push us to isolate and hide, which naturally sinks us into unhealthy shame. Our hesed helps us regulate the emotional energy of shame.”

— The Other Half of Church

They talk about a template for this sort of conversation — a skill to develop as we seek to help one another be transformed by the renewing of our minds; as we proclaim the Gospel to one another to build hope and to persevere together — their template involves a reassurance of the hesed — the love — that connects us to God and each other, and by saying “I believe you did this,” not “you did this,” invites a conversation and listening.

“I love you but believe that you stopped acting like yourself. Let me remind you how we act in this situation.” — The Other Half of Church

Framing the “spur” or prod as a recognition of where we have stopped acting like who we are, with an invitation back to shared values and action, does not cast out — like bad shame — but invites closer; prodding; spurring; encouraging. It is a terrifying idea, right?

This sort of speech takes real love; and real agreement on shared values for it to be helpful.

We will not always get this right; and sometimes someone might raise something with you, in love, where they are wrong — that is an opportunity for more encouragement, and perhaps to invite spiritual parents — those more mature than us — into the mix if it feels like it is going wrong.

Our habitat will shape us not just when we structure our physical environments right, but when we fill them with people filled with God’s Spirit — God’s household — who love us and direct us towards Jesus.