In a recent Gospel Coalition Australia article ‘Why You Should Ditch Your Digital Bible,’ Matt Smith made a compelling case for the priority of paper Bibles over the modern technological solution; the digital Bibles we now carry around in our pockets on the screens of our smart phones or tablets.

Smith concludes:

“But, in consistently choosing them over paper Bibles, we are inadvertently robbing ourselves of the opportunity to store up God’s precious and life-giving word in our hearts, contenting ourselves to sip from the fountain when we could be drinking deeply from it.”

His piece was a thoughtful engagement with an academic discipline sometimes called ‘media ecology.’ Media ecology is the idea that our tools — as part of the physical world (or ecology) we engage with — form us as people, it was pioneered by Marshall McLuhan.

Before the digital explosion, McLuhan predicted that electronic communication would collapse the barriers of space and time and create a “global village.” McLuhan drew on the insights of another scholar, Harold Innis, and his book Empire and Communications. Innis described how empires through history rose and fell based, in part, on how well rulers communicated their imperial vision and so formed their citizens; he saw lots of this boiling down to the technological choices these rulers made.

In the ancient world, you could choose between your messages travelling a long way across space, or lasting for a long time. A statue or inscription was permanently embedded in a place; whereas a verbal messenger could carry a memorised message from one place to another, but if that message was not written down, it lasted for just a short time. Writing on various transportable mediums (papyrus, for example) became a game changing technology, because messages could be carried a lot more easily than big stone tablets, from one end of an empire to another. McLuhan drew on Innis to argue that in communication, content matters, but so does the form we receive it in (“the medium is the message,” he said). Communication choices are ecological; the technology we introduce into our lives forms us.

McLuhan also recognised technological choices actually occur before questions about carving words into rock, or writing in ink on papyrus; writing, even the alphabet, is a technology. When writing was introduced, producing a shift from oral to written transmission of information, people then observed it would have the effects Smith identifies digital bibles have on us moderns. So Plato, quotes Socrates on the danger of writing in Phaedrus:

“If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls; they will cease to exercise memory because they rely on that which is written, calling things to remembrance no longer from within themselves, but by means of external marks.”

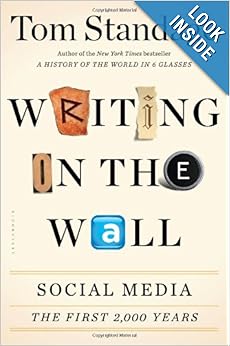

Smith joins a long line of people concerned about the impact technology will have on us as people; and asks good questions about how the forms and things we introduce into our reflections on God’s word, might shape how we receive and are transformed by God’s word. Tim Challies wrote a book on this titled The Next Story, back in 2011, while Nicholas Carr wrote a more generic look at how technology is affecting our ability to think reflectively, and to remember things, in his 2010 work titled The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.

In the present Covid-19 age, we’re learning, perhaps more than ever, that technology disrupts. That our technologies aren’t ‘neutral tools’ but that they shape us as we shape our world with them; zoom fatigue is real, disembodied church mediated to us by screens is different, our ability to have side conversations and monitor body language and make eye contact properly with others limits our ability to connect. Thinking about how we shape the ecosystem that shapes us is an important part of thinking about our formation as people, and for followers of Jesus, how we are shaped as disciples. Our technology habits are part of the disciplines that will disciples us; and as Faith For Exiles a recent book on discipleship in ‘digital Babylon,’ by David Kinnaman and Mark Matlock puts it “screens disciple.”

Screens also disenchant. There’s a romance to tactile and tangible objects; like books, with their paper selection and typesetting, and smells, part of the ‘form’ that forms us as people (even if we don’t notice it). Technologist David Rose wrote a book a few years back titled Enchanted Objects: Design, Human Desire, and the Internet of Things, where he pitted two visions of the future against one another; a vision where the world is overtaken by interactive black glass services that serve up whatever content we desire; a kind of global village where space and time (and all human limits) are eradicated as we ‘plug in’ — versus a world where tangible objects are given ‘tech powers’ to make them function like tools from the pages of a fantasy novel. He suggested one is more ‘human’ and more aligned with our desires and our embodied interactions with the world. He remembered growing up with a grandfather who had an array of woodworking tools in his shed; one for every occasion, and bemoaned the rise of the one size fits all tool; in part, because of the ecological impact such changes might have on us as people.

I have strong sympathies with his concerns. I read digital books on a kindle rather than an iThing, and I prefer public Bible readings in church from a paper Bible, while I use my phone when in the pew. But this is an area for us to pursue wisdom, not prescription, and not a silver bullet piece of theologically endorsed technology (whether pixel, or ink).

And yet, Smith’s arguments about the reduction of God’s word to pixels on screens — that it enables distraction, limits context, and limits retention — can also be made about every other publishing decision made around God’s word. The way to counter the impacts he observes might not simply be about the best technology, technique, or medium, but the ecology around those mediums.

His argument about context can also be mounted in a different direction about the decision to compile the Bible, a library of books, into one book — which emphasises the coherent whole at the expense of the 66 individual books. Then there’s the question of ‘which context’ one brings to a passage. Smith defaults to the surrounding passages, but our interpretive context is bigger (and one we bring to page or screen), whether the individual book, or the narrative unity of the whole Bible; centred on Jesus as the Messiah who fulfils the Old Testament in his death, resurrection, and pouring out of the Spirit. It is good to ask how our media decisions frame our reading in any direction, so we might push against that. It’s possible that a hyperlinked Bible connecting you to the Bible’s 63,000 inter-textual references might actually help you appreciate the context better than one that keeps you rooted in one passage.

Martin Luther harnessed the power of the printing press to kickstart the Reformation. He was deliberate in its use; recognising its power remove the authoritative gatekeeper role of a priesthood that kept the word obscure in part by medium decisions. The church kept the Scriptures bound up in hand-transcribed Latin copies. The Reformation was supported by its ecological and technological approach. Printing the Bible, in the vernacular, supported the idea of the priesthood of all believers. Luther chose a technology that supported the re-formation he was hoping to see in people and the church. He chose forms that were not as limited by space and time as those he replaced, and so spread both the Gospel, and the message of the Reformation further and faster than the Catholic church could (and had it adopted the same technology, doing so would undermine its theology). Luther also cared about the physical form of his publications, in a letter complaining that “John the printer is still the same old Johnny,” he says “they print it so poorly, carelessly, and confusedly, to say nothing about the bad types and paper.”

The printed word has a certain sort of formative effect, and part of that comes from a connection to the physical world; part of a decision to read from a paper Bible is an act of resistance, or disruptive witness, against the world of black glass and instant gratification; and we should embrace that to push back against the formative power of screens. But screens — and digital communication — also collapse the limits of space and time; like the alphabet, paper, good Roman roads, and the printing press, they allow the message of the Gospel to be transmitted further and wider and faster than ever before. Smith makes the case that a printed Bible a formative tool. It is. But if we bring an ecological framework to the question of how we access and share the text of the Bible, it’s not our only tool, or always the best one.

The trick with our ecology is to remember that the Bible itself, from start to finish, is not meant to operate in an ecological vacuum. As a communicative act from the divine; an act of Revelation from God, the Bible is relational and is to form part of a broader ecology. For Israel, the Old Testament was received by a community, and created a community with a particular sort of formative ecology; a community that enacted a series of festivals, and liturgical practices, that ate together, that memorised its words, that prayed and sacrificed, that dressed differently to the people on the outside; an interpretive community that lived out the distinctives the Bible called for, and so became a formative community. Operating as a priestly nation; God’s image bearing people revealing his nature and character to the world; God’s images aren’t statues rooted in one part of the empire; they live, breathe, speak, and love.

The New Testament continues this trajectory; but marks an even more substantial act of Revelation. In the New Testament the word that spoke the world into being becomes flesh, and makes his dwelling among us. In the New Testament, authors take advantage of new communication technologies that are available to transmit the message of this word becoming flesh, in fulfilment of the Scriptures, as far across the world as they can; and as people believe the message, it creates a new interpretive community; a new community of people in relationship enacting the message they receive. The church. Whatever form the words of the Bible take in our lives, whether digital or printed or spoken, as we receive them, they come with a broader ecology that forms us. John, who wrote about the word becoming flesh at the start of his Gospels, often, in his written work — a medium decision — acknowledges the limits of that medium because they aren’t fully enfleshed. He says on two occasions “I have much to write you, but I do not want to do so with pen and ink,” he desires to be there in person.

Perhaps the answer Smith is seeking as he employs a hard copy Bible when sitting down to read with students, and encouraging them to do likewise, is not simply in the medium decision he makes about a paper Bible versus a digital one, but in the decision he’s also making to share not only the Gospel, but his life as well, as he reads with others.

Perhaps the biggest problem screens and i-devices contributes to is not the disconnection from the word Smith identifies, but a disconnection from others — perhaps screens serve to individualise us, where the message of the Bible is one that draws us together as a community of priests, called to let the message of Jesus dwell among us richly. But books can do that too.

NOTE: A shorter version of this may or may not appear on the TGC Australia page later this week.

NOTE 2: Check out an old hot take I wrote on a similar argument from someone else. I think the building blocks of my response are the same, but I’m much more sympathetic to the argument about paper now than I once was…