This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

Who — or what — is ruling your life?

We started this series in Athens — a very religious city (Acts 17:22–23) — where figuring out the answer to this question was obvious. There were temples and altars where you’d sacrifice time and money to show you were ruled by these gods.

This is where Paul announced that God had called all people to repent and be ruled by Jesus (Acts 17:30) — to meet the God who made us to inhabit time and space so we might find him (Acts 17:26).

We might not have altars and temples, but we’re all sacrificing our time and money in spaces that show what rules us. We might answer the question by looking at where we’re spending money — though everything seems to cost so much at the moment — or looking at where we’re spending time: more time than we need to, so we’re sacrificing other things. It could be work… or family… or the gym… or church… it could be what we’re working for that we don’t have yet.

We’re still very religious. We still sacrifice our time and money for whatever or whoever rules us — even if we rule ourselves.

But hopefully, for most of us, the answer to the question “Who’s ruling your life?” is Jesus.

And I guess I want to ask: how would you know?

Can you spot the difference between your life with Jesus and without Jesus? Does your life look different to your neighbour’s? Are you inhabiting space and time differently as someone who has found God?

Sure — we might hang out here once a week, or a couple of weeks a month, or once a month. And we might go to growth group, or even have a few spiritual practices we’ve incorporated into our daily rhythms, and we might try to do good stuff with a sense that God’s in the mix somewhere…

But are we living in a different economy — with different objects of worship and a different approach to time and money?

If we’re not, how are we meant to resist the pull of the idols of our age — resisting the rule and the promises of dead gods?

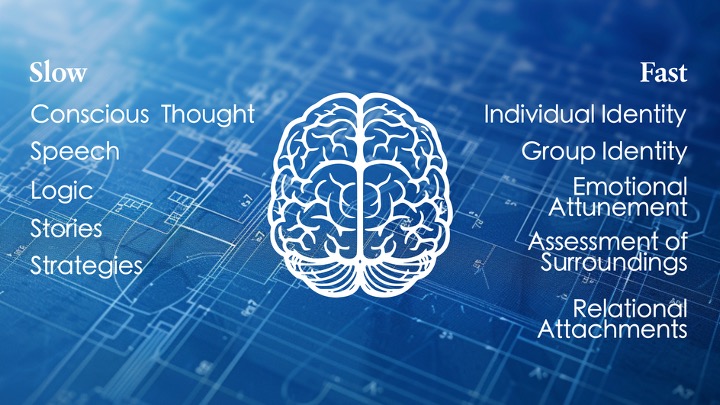

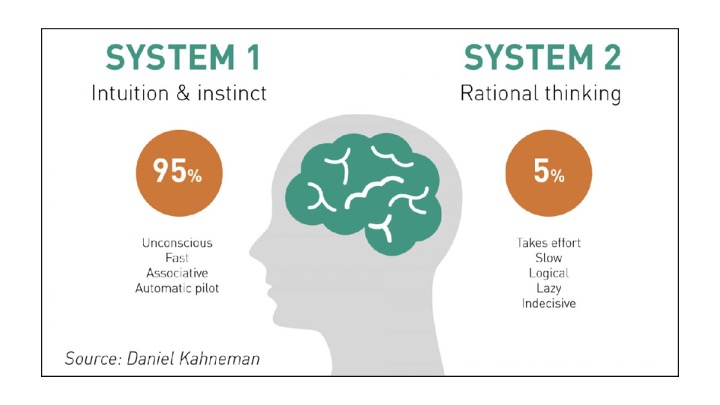

It may be that Jesus is ruling one part of our minds — the rational part — while our lives are playing catch-up… or still running the show.

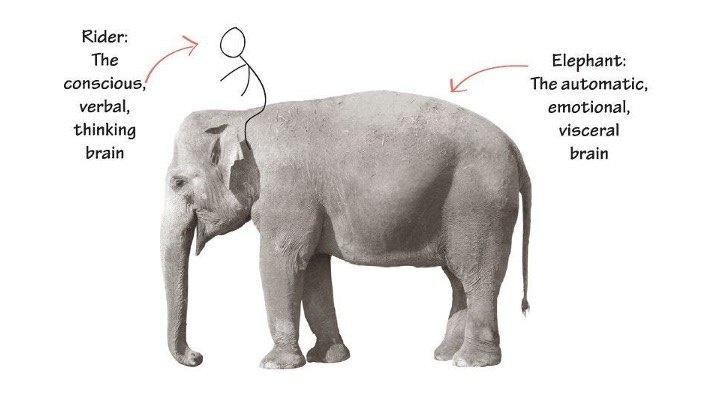

Right back at the start of this series we looked at this idea of our minds being like a rider — the rational bit — and an elephant: our deeper, emotional self — our loves and identity and attachment and belonging.

And the elephant isn’t formed by knowing more, but by experiencing love and belonging and joyful connection that brings us into alignment with whoever or whatever it is ruling our hearts.

Who’s ruling your elephant?

Are we ruled by the patterns of this world — like the idols and architecture, the habitat, in ancient Athens — or by Jesus renewing our minds? If we want to be ruled by Jesus, we should probably set up our lives expressing that rule. This is where the idea of a rule of life comes in.

To be a disciple — to be ruled by Jesus — is to practice what he teaches and commands (Luke 6:46), and to come to him to learn his ways: to throw off the heavy burdens of self-rule, and self-justification, and sacrificing on altars of deadly gods… to find life in the one who sacrifices himself to give us life and rest (Matthew 11:28–29).

A rule of life is an expression of being ruled by King Jesus — the king of rest. Finding life in him, not the idols and temples of this world — not because you have to, out of some sense of legalistic obligation to earn his favour, but because he has given you his life and invited you to come to him and learn a way of life that is good and beautiful and gives rest to your soul.

And so, as we wrap up this series, I want to encourage you to carve out space this week to start building a rule of life — a guideline that shapes your habits in time and space — or to keep building on what’s already established.

We’ll recap some ideas, and it’d be great to turn those ideas into practices: to write some things down, schedule them in your diary or calendar, take notes on your phone — start the work of establishing, or building on, habits that show you belong to Jesus.

I’ve got some tips here from the world of habit-building.

First: start small. Don’t try to pull off a massive revolution of your life all at once. We know what it’s like to make big resolutions and then have them drop off a week or two later.

Second: start with habits you’ll enjoy. There are lots of disciplines that will feel hard and restrictive. These are good. But if we’re building a rule of life from scratch, let’s start by adding a thing that will bring joy — that we’ll want to stick to. This will be different for each of us because we’re all wired differently, and in different stages of life and circumstances, with different rhythms we’ve already established both to survive and to grow.

You might love the idea of solitude and a quiet time with God. Quiet times are an evangelical sacred cow. But I hate them. I want a noisy time. I want to talk about the Bible with other people. I chucked a little two-page thing about how different personality types resonate with spiritual practices differently in the Facebook group earlier this week.

I’m not saying we shouldn’t ever establish hard habits, or disciplines that hurt — but…

This is where tip three comes in. There’s this idea of stacking habits: connecting new habits to established habits. We all have habits already — regular routines. When we link new habits to existing ones, they act as cues. Something like: “When I get out of bed in the morning” — that’s a habit — “I’ll make my bed straight away.” But we can connect spiritual disciplines to these moments too: “Before I get out of bed each morning I’ll pray.”

Then, as you’re ready to add something new into your rule of life, we can build it on the last habit, or on another regular routine.

“One of the best ways to build a new habit is to identify a current habit you already do each day and then stack your new behavior on top. This is called habit stacking.” — James Clear, Atomic Habits

Tip four is kind of from the series already: habits follow cues — which often come from our habitat. Energy or effort we invest in controlling the environments where we want the habits to happen, to prompt these habits, will pay off by reducing the energy involved in fighting to make a choice.

“Instead of summoning a new dose of willpower whenever you want to do the right thing, your energy would be better spent optimising your environment.” — James Clear, Atomic Habits

As we craft a “rule,” remember: this isn’t about legalism. It doesn’t save us. You don’t have to do this. This is about carving out space and time to know Jesus and become like him.

It’s also not a self-improvement exercise, where we’re discovering the realest and truest and best version of ourselves, or getting better at self-rule. It’s a discipleship exercise where we’re seeking to come to Jesus and learn his ways.

This means we’re not just deciding who we want to be, but discerning where we’re not like Jesus, and where we think God might want us to grow by his Spirit. And that happens in community, not in isolated introspection. You might want to talk with a trusted sibling in Christ about what this will look like in your present season of life.

And this isn’t self-improvement that we discern together, then do by ourselves. We live and belong and are formed in community: the household of God — which operates in our households, and in our growth groups, and as a church. We’re also practicing the teaching of Jesus who turns us out from ourselves and commands us to love God and love our neighbours as we love ourselves (Matthew 22:37–39).

So the first step in this process will be reflecting on how you want to become more like Jesus.

Do you want to be more loving? More patient? Is there a fruit of the Spirit you want to cultivate? Is it something in how you see him speak or treat others — closer to our Father in heaven? More shaped by his word? More self-controlled? Wasting less time — resting more? Using this season well? Giving an inheritance worth something to the next generation?

Is there a habitual sin — an act of disobedience to Jesus — that you want to replace with a habitual obedience, where you can interrupt and redirect that process?

Identify how you want to become more like Jesus, and then pick a small step to take to head in that direction.

Picking the small step to get you there might be tricky. You could look at someone else who has this characteristic and examine their lives, or dig into the Gospels and see how Jesus does something. There are stacks of practices you might slot in here.

We’re going to recap some of the ideas from this series, and as we go you might want to take note of ideas you could bring into your daily, or weekly, or yearly rhythms — and ways you might reshape your life. The ideas that resonate most with you. The low-hanging fruit.

As we recap, one of the other things we did back in week one was imagine how life might have changed for Dionysius and Damaris — these two citizens of Athens who met Jesus through Paul’s preaching (Acts 17:34) — and how they might have started to embrace the rhythms of the early church we see described at the very beginning of the church in Acts 2 (Acts 2:42).

There’s nothing radically new in any of the practices we’ve covered this series. They’ve mostly unpacked the way of life described for those who have repented and found life in Jesus’ kingdom, under his rule.

If you pick a habit from Acts 2, you probably won’t go wrong — whether it’s being devoted to the apostles’ teaching — the Scriptures — to the breaking of bread (which I take to mean participating in the body of Jesus and remembering the gospel together at our tables), and to prayer, and to generosity: to living a common life and sharing our possessions and wealth — what God has gifted to us — with each other and the world in a generative, life-giving way (Acts 2:44–45), habitually meeting together and praising God — gospeling each other (Acts 2:46–47). And look: as the church community takes on these habits, their life overflows to others. It’s contagious (Acts 2:47).

So here’s a chance to jot down some areas you want to build something different: where you might establish a new regular routine — a way of life where you’re seeking to be ruled by Jesus as you inhabit space and time.

You may not have picked this up, but across the series we thought about inhabiting space and time — and we started small in each category and expanded.

So — in space — the smallest thing that belongs to you, that is ruled over by you (or whoever rules you), is your body: your life. Jesus calls you to build your life like a house — to build wisely — by hearing his words and putting them into practice (Luke 6:47–48).

You might want to build a habit of engaging with God’s word in a way that leads to reflection and practice. Maybe “no Bible, no breakfast,” or “I’ll read the Bible with my household each evening at dinner,” or “I’ll listen to the Bible on my commute.” Or you could download the Lectio 365 app and start an ancient practice of reading, prayer, and reflection.

We don’t live alone. Some of us might be sole occupiers of our homes, but we live in a household: the household of God (1 Timothy 3:14–15). And we’re formed by relationships. Ideally, we learn to grow up connected to God and one another in relationships of joyful attachment and hesed — committed love.

Our brains are shaped by joy, which, according to the science, is transmitted through our faces and eyes as we experience others being glad to be with us. Not all of us grew up with this, but you might habitually introduce joyful connection within your relationships: make time and space for eye-to-eye, face-to-face connection.

“Our identity is built and formed by joy-bonded relationships. The identity center in our brain grows in response to joy… If joy is transmitted primarily through our faces and eyes, we need to practice letting our faces light up with each other.” — Jim Wilder and Michel Hendricks, The Other Half of Church

We thought about shaping the physical spaces we occupy as habitats for true humanity.

Like tradies who have jigs for repeated actions, we can rejig our spaces — and I know some of us already have. If there’s a sin you feel ruled by, that you’re habitually struggling with, what are the environmental prompts that cue up that behaviour or enable it? How can you act to remove or cut out the source — the cue — and replace it with something that prompts godliness instead?

Part of being deliberate about our environment, and about pursuing love and good deeds, is about filling our environment with people — especially people who will encourage and spur us on.

Habitually meeting together to share the good news of Jesus with each other (Hebrews 10:24–25).

This life together in our spaces sets us up to live in spaces we don’t control — a world, like Athens, where the architecture, art, and culture primes us for false worship (Acts 17:22–23).

As we learn that this architecture expresses and enforces misfiring parts of our human search for God, we can reorient our response from being conformed, or taking offence, or culture war, to our calling to be living images of God — those pointing others to life, those engaged in culture care: bringing beauty into this shared space.

What’s a habit you might embrace of cultivating towards what’s good and beautiful?

“Culture Care is a generative approach to culture that brings bouquets of flowers into a culture bereft of beauty.” — Makoto Fujimura

It might even be time in the garden, praying and growing things that delight you. It might be a habit of generosity and hospitality: habitually living as someone who’s received a good and beautiful gift from God, who shares at his table. Volunteering in a community. Making space for others. Baking for your colleagues. Delighting in God with an eye to what you might bring into the spaces you move in.

Our shift into time meant considering how we’re ruled by the clock, or the calendar — learning to number our days so we live wisely (Psalm 90:11), redeeming the time (Ephesians 5:15–16).

This means — at least in Ephesians — carving out time each day to remind ourselves that we live before the throne of God, as those raised and seated with him. Making space for prayer and worship: praising God for his goodness, knowing God, living in his presence so that each moment becomes holy.

You might rethink how you structure your day — like the psalmist (Psalm 119:164) — and many Christians through history who carve out regular moments for prayer. There are apps for this, like Every Moment Holy; they can act as prompts. So can daily reminders in your calendar app.

Now, if this flood of ideas feels overwhelming, remember: we’re just trying to pick one or two.

When it comes to the shape of your week, as one following the King of rest, you might want to carve out deliberate time to do this with a practice of Sabbath (Matthew 12:7–8): setting aside time to stop, rest, delight in God, and worship.

So we learn to resist the pull of our version of Athens and its altars that demand sacrifice — or our version of Egypt and its slavedrivers — or even from living as slave-drivers in what the Nap Bishop, Tricia Hersey, calls “the violent culture” that views our bodies as machines.

Carving out time to know God and receive rest for our bodies and souls will mean we work differently. It will mean we can approach the good works he’s prepared for us — and everything we do — as though we’re working for God.

“…this violent culture that wants to see us working 24 hours a day, that doesn’t view us as a human being but instead views our divine bodies as a machine.” — Tricia Hersey

Habits of time are trickier when it comes to seasons — but maybe as you figure out what habits to embrace, you might ask “When am I?” How does serving God not just in this moment, but in this period of life, look different?

We’re all working out how to make every moment count as heavenly: to always give ourselves fully to the work of the Lord, in every season, because the resurrection means this work is not meaningless (1 Corinthians 15:58).

You might have a lifetime of great habits so this all seems silly — but have never stopped to consider how life in this season, where you’re older and more mature and facing ends not beginnings, can be used as a gift — and how to keep growing towards eternity as it feels like you’re finishing up.

I love the idea of the church being like a time machine that teaches hope as we come together in different seasons.

You — or us — older folks might help us — or you — younger folks navigate living in time in seasons that are present for us but past for you. Us younger folks — and especially our babies and kids — might help older folks focus on what inheritance we’re investing in leaving behind.

But all of this is about learning to see time differently: as eternal, and revolving around Jesus. So we might embrace rhythms across our year that embed us in the story of the gospel.

You might start following a church calendar, or a lectionary, or a Bible-in-a-year reading plan — even at the end of life — to learn to see that time isn’t getting away from us, but always going somewhere: taking us somewhere.

Which we saw means working to store up treasures in heaven; living as heirs who inherit eternal life as the household of God (Titus 3:6–7). So our habits now are about us seeing the long term, and building on becoming the people we’ll be forever, with the people we’ll be with forever.

Our relationships with each other aren’t temporary, but eternal.

So, as we build a rule of life, this is our horizon. Which means each moment, each step — they’re not urgent. But each habit we build — the lives we build together — that God builds by his Spirit — they’re important.

Important enough that I reckon it’d be great for you to spend some time this week making a start… building some habits as part of expressing Jesus’ rule in your life, and becoming like him.

You might want to take up one or two — or some daily and some weekly. But make them manageable. And when they feel routine, add another.

Take the time to set up your environment to make this something you do. Ask your growth group to check in. Take up a habit together. Put reminders or prompts into your phone, or your diary.

If this doesn’t feel like enough… if you want to go bigger… some of our growth groups have been working through the Practicing the Way course this term — which is where that video came from. They have an online rule-of-life builder you could try out.

But we don’t just want to think about our individual rule of life, but how we live together. Whether that’s in households — whether they’re biological or spiritual households — or in growth groups, or even here together.

But let’s start in our homes and where we meet together in homes, and ask what it looks like to have regular rhythms and routines where we cultivate joyful connection to God and each other, in households bound by God’s love.

For us to be deliberate, and calibrate what we do with our time: what we do routinely, how we meet together as those ruled by Jesus — to explore how.

We’ve covered a lot of ground in this series, and it would be overwhelming to do it all at once. But the goal has been for us to see our lives in time and space, minute-by-minute and centimetre-by-centimetre, be more and more ruled by Jesus, so minute-by-minute and centimetre-by-centimetre, we become more and more like him.

King Jesus promises to give rest for our souls, as he reconnects us to our good Creator who gives us life and breath and everything else — and promises to do this forever. Let’s be ruled by him together.