There’s a beautiful metaphor of unity in the Gospels.

The table.

This is a particular thread in Luke’s Gospel where we witness Jesus going as a guest into the house of sinners, feeding people abundantly, and eating with his disciples and offering bread and wine as a picture of our participation in his death and resurrection and being made children of God who can eat at his heavenly table. The table, and who has access to it, has been a powerful picture of belonging in church history — different church traditions have different approaches to the table, some open it to all, as an invitation to be part of God’s family — an altar call of sorts, others ‘fence’ it, offering it to those members of the community the leaders of the community know to be Christians — taking seriously Paul’s warning to the Corinthians about ‘discerning the body’ in the meal (and understanding that both being about discerning the body of Jesus in the bread, and the body of Jesus being the community one shares the meal with — believing a person must be able to do both to truly be celebrating unity with Christ and his people).

There’s a backstory to this idea of sharing at the table that goes right back to the Garden at the start of the story of the Bible; the Garden where God as host declared all the fruit of the trees he’d put in the garden ‘good for food’ — except for one tree — and Adam and Eve decided that despite God’s prohibition, despite God being the good and generous host of an abundant table, they would declare what he called evil “good for food,” and they took it, and they ate it, and they were expelled from the table. God’s abundant provision of hospitality and a feast was celebrated through Israel’s history in various ways, including at the temple and through feasts and festivals, and Psalm 23 is a poetic picture of God’s abundant, overflowing, hospitality that must surely have had Israel salivating when they too found themselves cut off from God’s table during exile. Jesus restoring people to God’s table is a big deal; a deal the tables we operate in our churches points to — a return from being banished from the garden and exiled from God.

The table is a powerful picture of God’s hospitality to his family. But it’s also a powerful picture of relationships where difference is acknowledged. The tables Jesus eats at in Luke — those of the pharisees and tax collectors — are not the table Jesus operates as host. His presence there does not make the people he eats with part of God’s family, but it makes them people he loves and wants to eat with in order to love his neighbours and his enemies and invite them to the greater feast. This culminates, of course, with Zacchaeus, the lost tax collector who comes home to God as he invites Jesus to eat at his table. This difference is a really significant feature; we Christians sit at tables with different people at different times and express different things in that sitting; the table I eat with my church family and the table I share with my family in our home, and the tables I host with my friends, and the tables I am hosted at in public place, or the tables in the homes of other people all mean different things, and I occupy a different seat and a different role each time. To invite someone into my home, or to share in the Lord’s Supper (or communion) in church, is to invite people into the life of my family or the family of God, and the latter is in a different way to the way we might invite people to share dinner with us at church.

I wrote a few things during the debate about same sex marriage in Australia, and around the position the church was occupying as scandals around church abuse and domestic violence broke in the media to make the point that Christians now don’t occupy the place of honour at the public table we might have once assumed. We need to relearn the art of receiving hospitality in the Australian community, and indeed, it’s possible we’re now so on the nose, and that our social capital is so low, that we might need to learn what it looks like to be excluded from that table all together; it’s not a table that operates with the same grace that our Lord’s table operates with, we actually might need to earn our place at the ‘public table’ in the public square.

The table also has some interesting dynamics in Paul’s letter to the Corinthian church beyond how Christians treat the table when it comes to sharing dinner and sharing the Lord’s Supper (or communion, or the Eucharist, depending on your theological tradition) (1 Corinthians 11:17-34). The sorts of tables Christians eat at as guests matter; how joining a table is perceived and what it represents to others, and for themselves, matters.

Christians are not to eat in idol temples or share at tables of idol temples in Corinth because they belong to God and his kingdom; to eat at an idol’s table is to unite yourself, to commune, with that idol — or to be seen to by others, whether the idol is nothing (which is why Paul is happy to eat meat bought in the markets that had been sacrificed to idols), or there is something more substantial going on (which is why Paul says not to ‘share in the cup of demons’ in the idol temple). Christians shouldn’t participate in the hospitality of other gods, and eat at their tables — both because of whatever Spiritual reality is at play, and the perception that would create about the exclusivity of Jesus (1 Corinthians 10:16-21) — but they should enjoy the hospitality of those who follow other gods, their neighbours. We’re also to put the unity experienced at God’s table above all other forms of unity — his table shapes our approach to all other tables. We’re not to eat at tables we might feel free to if it destroys the conscience of the members of the body of Christ who share God’s table with us (1 Corinthians 8:9-13). So Paul expects Corinthian Christians to eat in the homes of their neighbours as guests and do so freely until their host tries to make the table a table belonging to an idol, so that to eat is to participate in idolatry, or express a ‘belonging’ to that god’s table (1 Corinthians 10:27-28). We’re not, with our table manners or our eating to call evil “good” with our actions, but nor should we call what God has declared good “evil.” This is the line Jesus trod so artfully as he ate with sinners, despite the Pharisees believing that ‘bad company’ corrupted. Israel had some pretty intense table fellowship laws that ruled out ever eating with gentiles and especially ever eating ‘unclean’ or idol food.

David Fitch has this really great picture of three types of table we Christians participate in as individuals, that maps nicely onto a corporate metaphor of the table — how we run tables, and participate at them in a more ‘institutional’ way. In his book Faithful Presence: Seven habits that will shape your church for mission, He talks about this in terms of ‘circles’

The first table

He talks about our churches operating the table where the Lord’s Supper is served as a practice that forms us as Christians, where we invite people to put their trust in Jesus, return from exile from God, and receive his hospitality as children. It’s like Jesus holding the Last Supper with his people, those who belonged to him who share in his body and blood and will share in the heavenly table. There’s a picture in the Gospel of someone who is grumpy at just how far the invitation to this first table extends — the older brother in the story of the prodigal son who grumbles that the father will let anybody who comes home and is recognised as part of the family eat, no matter how far into the world of exile they’ve wandered (partying it up in gentile cities and then wanting to eat pig food is about as far from Eden or the promised land as it gets).

The second table

This formative practice of sharing at what is essentially God’s table, where we extend his hospitality, then shapes how we operate the tables in our homes, or the meals we conduct as hosts. We get caught up in the hospitality of God and generously invite all comers to our tables, not just those who might give us something (like increased status — which was a sort of Roman hospitality practice the Corinthians were falling into), but those who can’t, and not just those who belong to our household or family (another Corinthian practice) but those who don’t. This table though doesn’t mark out the people of God; it marks out the people we extend love to and invite; it’s perhaps more like Jesus feeding the 5,000 as a picture of being the good shepherd who ends exile. It isn’t really just our neighbours either, the great act of Christian love is that we, like Jesus, invite our enemies to the table with us, to practice hospitality at this table is to invite all comers, to not draw lines or boundaries, to not exclude but to welcome, include, and to feed. There’s a picture in Luke’s Gospel of the sort of person who refuses to share this sort of table with others who belong — the Pharisees who mutter and complain that Jesus eats with sinners and tax collectors, or that he lets an immoral woman wash his feet. They don’t want this sort of relationship building with others to happen. This doesn’t mean turning our guests into co-hosts though, that’s a different sort of table.

Everybody worships; everybody has a ‘temple,’ but not every table is a temple; not every meal is an ‘idol feast’ — not every one of our meals is ‘the Lord’s supper’ — we are called to share a table with all sorts of people. Like Jesus did.

The third table

Fitch says our practices at these first two tables also shape how we operate in situations where we are guests — and I’d suggest where we are co-hosts (those times where it is not so clear that hospitality is being extended, but where participation at a table is mutual). When we eat as guests, with our neighbours, like Jesus with both the Pharisees and the tax collectors, our eating does not signify that we belong to their ways of seeing the world, we eat as those who belong to another table, bringing the virtues and values shaped by experiencing that love and hospitality, and being prepared to lovingly challenge the sin of those we eat with, but also to invite them to enjoy a taste of God’s hospitality at the other two tables.

The tables and the institutional church

When it comes to public, institutional, Christianity, church institutions or organisations decide who and how the first table operates — whether it is open to all without prior expression of faith and an indication of belonging to God’s people, or fenced; normally requiring baptism or membership in a particular community.

Church institutions, through their leadership and history (depending on the structure of the church), “discern the body” and decide what marks out someone as ‘included’ in the body or not — this can be justified along the lines of the church having the keys to the kingdom, or the table. If the church is to be an institution, as it has become through history, someone or some set of rules, ends up guiding the use of these keys or access to the table.

Different church communities, and different denominations, apply all sorts of different standards on who is seen to be part of the body — the line is drawn through discernment. This seems to be a totally normal function of our creaturely limits and church history. There are significant disagreements within the church — amongst Christians — around significant questions such that some churches would not let me share at their table, while I am given (by ‘ordination’) the ability to decide who gets to participate at this table in our community.

The first table, Biblically, is one that it is right to limit to Christians because of what we participate in as we eat (but I think it is legitimate to invite people to express their trust in Jesus and participation in the Gospel by sharing in the Lord’s supper as a first step, and to wrap baptism up in this sacramental package). This means that churches have to decide who they believe is a part of the body, and who isn’t. Again, different churches have different ways of drawing this line — different understandings of the Gospel and the way it works to unite people to Jesus, and different understandings of the sort of maturity required before one participates in the sacraments (so lots of Christians don’t baptise infants, and don’t invite them to participate at the table for various theological reasons). Those I am prepared to share at this first table with are those I consider to be Christians eating at the Lord’s table, not idolaters sharing in idol worship. This, too, requires discernment. My Presbyterian tradition (and the broader Protestant tradition) considered the Catholic Mass and the Catholic Eucharist to be in the latter category; if I were to visit an Anglican, Pentecostal, or Baptist church while communion were being taken, and I was invited, I would participate, just as I invite people from traditions outside of Presbyterianism to participate, based on an articulation of the Gospel, if they come to our table.

The church also participates in ‘second tables’ — and where it gets tricky is that we participate at second tables with each other, through ecumenical partnerships in politics, mission, or just seeking to acknowledge unity in the Gospel that might be expressed in something other than the table we run in our churches. To host, or participate at, a ‘second table’ doesn’t say anything substantial about the faith of the other, or whether they belong to God’s table or not. Such a table should be, if it is shaped by the Gospel, broad and inclusive. We don’t do anything to fence the dinners we host at our church every week; we invite all comers — we show that we are ‘hosts’ though by giving thanks to God for the food we receive and share. When I’m eating, and praying with, my friends who pastor Baptist, Uniting, and Anglican churches in Brisbane’s city I don’t lose my Presbyterian distinctives nor do I insist they become like me; there is differentiation and there is a pluralism at play in such gatherings that is not present when I invite people to table 1 at church. If we were jointly operating a ‘table 1’ type deal in some sort of combined service we could only do that (I think) if we agreed on some of the parameters; some parts of the ecumenical movement, historically, have — I think — failed because they failed to realise that these commonalities couldn’t be assumed and were legitimate distinctives. To that extent I think ecumenical cross-denominational boundaries fellowship should operate at ‘table 2’ acknowledging the capacity for many of us to share relationships at table 1 in different circumstances. We can also share table 2 with people who are not Christians at all — and indeed we should, but our operation of table 2 as hosts which is alway shaped by our table 1 practice should also have table 1 as its telos; we should want people joining with us in union with God. The ultimate expression of Table 1 is not in the church gathering, but in the heavenly feast those gatherings anticipate.

The institutional church can still sometimes participate in ‘third tables’ — examples are when institutional leaders speak ‘institutionally’ into public discussions, like contributions to debates about political issues. Sometimes third party groups — like lobby groups — represent a sort of ‘table 2’ Christianity; whether that’s a good idea or not depends on how deep the unity is, and how much such a contribution inevitably eradicates important distinctions and ends up pretending there’s a table 1 unity on political or social or moral issues where there is not (and where there isn’t even a table 2 type unity). Churches, and Christians, can sometimes even host third tables and invite other churches, and other neighbours, to participate at this table as guests, this happens when the emphasis of the table is not that the Christians are hosting as Christians, but as citizens — with some sort of ‘political’ ends not oriented (directly) to the heavenly table.

Our time’s table problems

We are, as Christians, and society at large, facing some major problems operating around various tables. Our society increasingly buys into a sort of ‘cancel culture’ such that people running table 2 and table 3 type tables are very prone to exclude others from the table where those others don’t buy into a particular way of seeing the world. There is no ecumenical spirit outside the church even with public catch cries of ‘tolerance’ and ‘inclusivity’ — these are extended so long as people obey the table manners our age expects.

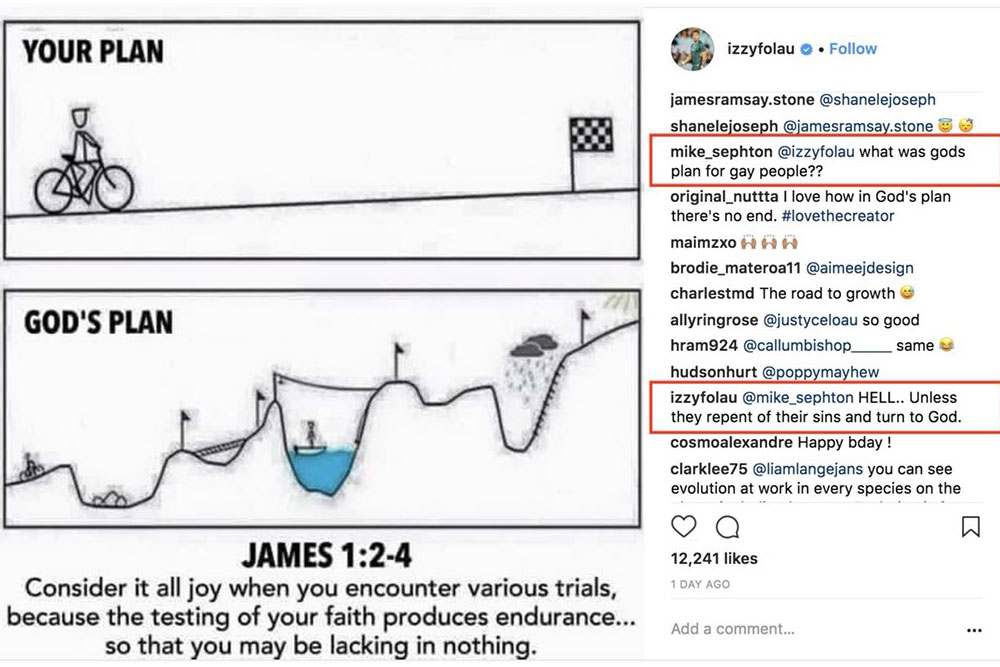

The question of hospitality and who it is extended to is used to exclude when a Rugby player shares a religious meme consistent with his sectarian views and is excluded from the ‘table’ of the national Rugby team, or when a TV talk show host goes to a football match with a former U.S President (who some believe should be tried for war crimes), or when a U.S political aide is asked to leave a restaurant as a result of her politics, or when a football player’s cousin is removed from employment from a religious institution he calls a synagogue of Satan, or when a religious school wants to hire or fire staff based on their personal convictions and behaviour, or when a Christian political lobby invites said Rugby player to share their public platform when that player explicitly denies the Trinity, or when an Archbishop of a diocese gives $1 million to a campaign about who our society will recognise as married, or when that same Archbishop asks people within his denomination who wish to change the platform to keep with public pressure to leave and start their own table… the issue is that in each of these issues, especially as they relate to how Christian relate to others (whether other Christians, or those we don’t consider to be Christians as we discern the body), there’s a different sort of ‘table’ at play and there are different principles governing who should and shouldn’t participate.

When Israel Folau instagrammed his meme I had an argument with a progressive Christian friend about whether or not it was legitimate for the National Rugby League (note, a different code) to pre-emptively refuse to register him as a player again on the basis of its ‘inclusivity policy’ while they were happy to re-register a player convicted of serious violence against women (Matt Lodge). I had an argument with a conservative Christian friend about whether or not Israel’s stance on the Trinity was a significant issue. In both cases those friends ‘cancelled’ me — blocking and unfollowing me — or uninviting me from a certain sort of table (a virtual table 2). I believe both would still welcome me at a table 1 situation if they were operating as host, but I suspect both would like me also not to have a seat at the ‘public’ table, sharing my particular views on the matter in the public square (given that the conflict arose in both cases because I did so, not because of the merit of the actual point I was making in each case). I would, for what it’s worth on the Folau case, exclude Israel Folau from my ‘Table 1’ scenario (because he denies the Trinity), invite him to ‘Table 2,’ and am happy for him to have a seat at Table 3 (in the Rugby team and on social media), so long as it isn’t labelled ‘Representative of Christianity.’

What happens in these virtual, personal, relationships happens on a wider, tribal, scale when it comes to denominations, but also theological movements — progressive and conservative — within denominations. Conservative denominations seem to be responding to pressure from outside their bounds by tightening the boundaries, while some people within such denominations — either because they see this change happening and want to preserve something good, or because they are compelled to change for reasons of progress or reform — are looking to push for change. Both forms involve change to who gets a seat at the table. Progressives in positions of power in denominations have often silenced, excluded, or expelled those with conservative convictions; or, in the course of progress, made belonging so untenable or a lack of welcome so clear, that more conservative people and churches have been pushed out. Conservatives do the same. There’s, though painful, a legitimate Table 1 reason to push for such change, and opposing parties, would, I believe, be better off generously parting ways, and sharing table 2 relationships (pluralism) rather than having different approaches to God (polytheism) under the same umbrella (which at times might be tantamount to creating circumstances that are the equivalent of ‘sharing the cup’ in idol temples — and I’ve seen plenty of rhetoric from progressive Christians suggesting Davies and the Sydney Anglicans have departed from the Gospel).

When Glenn Davies gave $1 million to the No Campaign it was, I believe, a bad decision because it was a decision that seemed to me to be seeking to hold a position close to the head of table 3; a position Christians no longer occupy in a post-royal commission world. It was a decision to invest not just financial capital, but social capital, in a cause that sought to exclude people from a type of table 3 (the public institution of marriage), in a way that communicated such people were not welcome at table 2, or table 1. It prevented the problem, in many cases, of having to navigate table 1 fellowship with the LGBTIQ+ community — whether married or single — by functionally communicating a lack of welcome. The Anglican church does historically have a place at Table 3 in a Commonwealth nation that other denominations do not; it is an establishment church. The Queen is its head. I think this was a mistake because it was essentially an act of inhospitality in those tables that are not closed off to the people of God, or invitations for people to join the people of God. Tables 2 and 3 should be, as a matter of participating in a civil way in a pluralist society, as open, inclusive, and hospitable as possible and we should model that. Table 1, on the other hand, should be welcoming in a way that is not as inclusive because it excludes those who are not part of the body of Jesus.

For me the way I think this paradigm plays out, where Table 1 shapes one’s participation in table 2 and 3 (and where one does not participate), I think ‘Table 1’ is a feast for God’s family, with an invitation to come home. Not all are included. Table 2 is a feast for all to ‘taste and see’ that God is loving and hospitable, and all are not just welcomed but included at the table. Table 3, which isn’t our table to host, is our table to serve not to run, and where we have power or influence our job is to look to those being excluded and find ways to include them at that table, by giving them space at our table 2s (this is why I think the line the institutional churches in Australia ran in the postal survey, on the back of a history of Christians excluding LGBTIQ+ people, particularly in terms of legal recognition and protection, was such a problem). Where there is disagreement amongst those operating table 1s it is a matter of discernment; we have a responsible to be part of a table 1 that we believe ‘discerns the body’ appropriately, and leaders have a responsibility to set clear boundaries (by teaching and shepherding), and also by identifying ‘idol temples’ (like, for example, Folau’s church). Where one discerns that a ‘table 1’ is not an expression of the body, one must not share ‘table 1’ type fellowship, but one must still share table 2 and 3 type fellowship (Jesus ate with sinners and tax collectors).

The Anglican church is often described as a ‘communion’ — and that presents interesting challenges when it comes to the question of table 1 and the discerning of the body. Lines have to be drawn. I’m much more sympathetic to Archbishop Davies in the furore around his speech to synod which I believe was a (clumsy) attempt to ‘fence’ table 1 in a particular way, consistent with his appointed duties, and appropriately in a table 1 setting. Davies, as Archbishop, occupies a challenging position in that he has a sort of authority invested in him when he speaks on Table 1 matters for his diocese, that might communicate things about who he (and they) are prepared to sit down with in table 2 scenarios (as hosts or guests), and what tables they might avoid in table 1 scenarios as ‘idol temples.’ He also, for good or for ill, is often an authoritative, representative, Christian voice in table 3 settings — like the $1 million donation scenario — and that inevitably frames how his public proclamations about Table 1 are heard.

The challenge for the rest of us in parsing the reaction to Davies’ Synod speech on social media is that there are lots of different denominations and even local communities who operate their ‘table 1’ in very different ways to the Anglican communion, and it’s easy to apply our own standards to him and his speech in ways that might exclude him from any table. I recognise too, that his speech is a pitch to run the Anglican table — at least in Australia — in a particular way (one that is narrower than currently seems to be its mode). It’s not just that we hear him excluding vulnerable others from tables 1-3 as host — and he has been heard that way — others both inside and outside the Anglican communion have since turned around and sought to exclude him from tables 2 and 3. Davies has a particular responsibility for ‘his table,’ and it is within that responsibility, and the discerning of the body, that he made the speech he made. The reaction from the more progressive wing of Christianity has been stunning to me; mirroring the reaction to Ellen for daring share a table with Bush (and I’m sympathetic to the idea that Bush, in exercising the office of President, did some things that office required of him that were evil, I’m just not sure you can occupy any sort of office in a modern military state and not commit evil), perhaps because part of the progressive view of the world is seeing reality in systemic rather than individual terms, hospitality is something offered categorically rather than personally, there’s also an echo in the progressive celebration of a restaurant in the U.S refusing to serve Trump staffer Sarah Huckabee Sanders. There were think pieces pondering whether Jesus would eat with Sanders (I believe he would, at the very least in a table 2 and 3 way), and whether it’s ever right to share hospitality with an ideological enemy (it is if you’re a Christian so that person is also your neighbour). The New Yorker ran a piece asking ‘Who deserves a place at the table’ (the nice thing about Christianity is it starts with the assumption that nobody does). It noted:

“Jesus—at least as he is reported, or invented, by the author of the Gospel of Mark—was the Kropotkin of commensality, blowing up the long history of Jewish food rules by feasting with publicans and tax collectors and prostitutes and sinners of all kinds. It was nearly the whole point of his ministry.”

It’s a piece that ultimately explores the paradox of tolerance, and lands on the solution proposed by the political theorist who proposed it, that a tolerant society cannot tolerate — or make space at the table for — the intolerant. I’m not sure the Gospel conforms to that paradox. Jesus did, indeed, blow up the food rules and eat with everybody — both pharisees, and tax collectors and sinners. But he also established a table that had boundary markers; the people who put their faith and trust in him and so received a spot at the father’s heavenly table, and those who don’t. He broke Jewish table fellowship rules in order to create a table that included gentiles; but it excluded plenty of Jews (the Pharisees, for example), and gentile idolaters. It’d be a mistake to see Jesus’ dining practices solely in terms of eating with sinners and tax collectors; he ate with people previously excluded to show they might be included in his kingdom by grace. Table 1 sets the agenda for Table 2, and Table 2 practices are a gateway to Table 1, but they are not the same table.

I’m also not suggesting Conservatives are better at hospitality; they tend to run ‘Table 2’ institutions as though they are ‘Table 1’ ones and to occupy positions of influence in Table 3 scenarios that don’t match up with reality (the ACL has a particular approach to this that could be its own post). I’m also not suggesting that Table 2 type hospitality is about denying difference or patching over serious disagreement; civility is not the goal, persuasion is, love is, unity is, and civility is the means. To not sit at the table together, whether for the pursuit of common cause, or to hear one another, is guaranteed to entrench polarised communities of ‘others.’ If, for example, Bush is a war criminal who should repent and be tried, but he belongs to a tribe that views him as a champion, how will his views about himself ever change without hearing voices outside his tribe in a context that recognises his humanity?

For the record, I don’t think Davies was telling LGBTIQ+ parishioners to leave, unless they are part of the movement to shift the boundaries the Anglican communion has traditionally established for those who can participate at table 1. Those outside the Anglican communion who practice a broader table 1 than Davies does (or than I would) have already made the decision Davies called for; there’s also a movement in Australia that has taken almost exactly the step Davies is now encouraging members of the Anglican church to take; one that absolutely fits an inclusive ethos that merges tables 1 and 2 — the Uniting Church. I’ve read comments from a stack of Baptists and Anglicans this week that basically just boil down to a wish for their denominations to become the Uniting Church, and were they all to do that, leaving those who want a distinction between tables 1 and 2 maintained, you know what they’d get… Presbyterians (just with worse forms of government). I don’t think Davies was telling LGBTIQ+ members to leave, because I’ll take him at his word — but I can’t help but agree with those hurt by his words that there is a context that frames them particularly negatively and compounds the hurt they cause.

Lots of my progressive Christian friends commenting on the Davies speech on Facebook seem to want ‘table 2’ type fellowship operating in a table 1 scenario; a broader unity and an extension of charity that goes beyond one’s (or an institution’s) discerning of the body; an eradication of a particular sort of discernment in favour of unity. There’s a danger there, at least from Corinthians, that believers eat and drink judgment on themselves, or participate in ‘the cup of idols.’ Table 2 fellowship amongst Christians of different traditions is a beautiful thing, and it’s a beautiful thing precisely when it is properly differentiated and we can discern areas of disagreement, and listen well to ideas that challenge us to be humble and broader than we might otherwise be at Table 1. Table 2 gatherings of Christians won’t work if we start insisting, or trying to, that table 1 should be shaped by the hospitality we’d like to see extended in the public space of table 3, or in our private gatherings around table 2s. Table 2s will collapse under that pressure; and the formative direction of the table, for Christians, is only really meant to work one way (though we might be formed to see the beauty and welcome of Table 1 by experiencing it at other tables). How we understand the Gospel, and the Jesus it reveals, should shape how we host and participate in tables beyond his; the tables we eat at in the world aren’t meant to cause us to revise our understanding of Jesus. The idea that ‘Table 1’ type fellowship should happen at Table 2 is cut from the same cloth as the ecumenical movement; we might, for eternity, eat and drink from the same table and we should be open to that possibility and rejoice, but the worst thing we could do is convince someone that is the case and then spend an eternity separated from them because we never challenged someone outside the body to move inside it.