This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

I need to give a bit of a content warning — we are talking about family — about parents — and I know some people have had damaging relationships with their parents, so this is a traumatic topic to engage with.

We are also talking about church as family — which, in high-control environments, is language that can be used coercively or abusively — probably in ways that overlap with those family experiences.

I am hoping we will steer clear of these dynamics, but acknowledge there will be an overlap with language that may have harmed you; deforming rather than forming some of us.

There is also a caveat I want to add up front; sermons have limits. The sort of ideas we open up today about our households, and our church as a household, might require deep recalibration of our lives. I am sketching out a framework for how we think of discipleship; our formation as children of God. This is a conversation starter, not a conversation finisher.

I am also opening with a confession. I am worried I am not a good parent; and the more time I spend with those of you whom I love, who have suffered at the hands of bad parents; the more I have seen the cost of these wounds, the more I fear how I am deforming my kids. I need help.

At home I am short-tempered. Distracted. Focused on what I want to do. Trying to cope. Parenting is hard. Kids are always fighting. Always noisy. Always too slow to do what I want. Our house is too small, and we just always feel angry at each other. It is overwhelming… and it needs to change. I need to change.

And look, I am on social media — I know I am not alone in this sort of feeling.

A few years ago Robyn and I visited these psychologists — a couple — who specialise in ministry families. If you have been around for a while you will know I have not always been great at work-life boundaries — another thing I inflict on my kids. Robyn is quite insightful; she had recognised that this was not sustainable for either of us before I did — and one of the things she brought up was that it is a real problem for her, and the kids, when I work from home; from the couch.

I reacted pretty badly to this — some of you will know I am in the family business; as a kid, my dad never felt available. In his first church he had an office across the yard from our house; we knew when he was in the office we should not interrupt. Then, when we moved to Brisbane, his office was downstairs — and the door was always closed. I had decided not to be behind a closed door; to be present and accessible. It turns out a clearly marked-off workspace is probably a wise thing — but — my folks had been looking after our kids, and when we picked them up after our session they asked, “What did you say about us?” — because you always talk to psychologists about your parents.

I told them I had brought up the closed door and how I worked from the couch so I could be interrupted; and Dad explained he had worked from home, in his office, because my mum’s dad — also a pastor — his office was in town, and he was always absent, and Mum did not want that.

Dad worked from home to be available and the door was closed because the air-con was on. I had to re-narrate that closed door… because, as you know, “love is an open door…”

It is funny how much I had been impacted by this part of my habitat; the closed door; and how my own choice with the couch was not a fix. I tell this story because it is a picture of how we learn to be human in a household. And how we set up our households is part of what forms us, and others — perhaps especially kids. And even if you do not have kids yourself, you are probably conscious of having been formed by those around you.

Last chapter we looked at the analogy of the human life as a house; one we each build either on the foundation of Jesus — or something else — where we take responsibility for building wisely (1 Corinthians 3:10).

This week we are mixing our metaphors — or building them up a little — moving from house to household. This is language we find through the New Testament; a picture of the church as a household — the household of God (1 Timothy 3:14-15) — not just a biological family. We modern Western folks are quick to equate a household with a nuclear family — and plenty of our experience of a household is a product of this move; our families — our households — inevitably shape us; our habitats shape our habits; we inherit patterns of life in the world from others — or define ourselves against them — like in my story; three generations of pastor-dads choosing where to work and messing up their kids.

We will look at 1 Timothy here, and while we will look at the content, I also want us to think about the nature of relationships this letter is operating in and trying to create. Paul is writing to Timothy — last week we saw Paul holding up Timothy as his beloved son who follows his example (1 Corinthians 4:16-17); his way of life (1 Corinthians 4:16-17). Also — while we are looking at 1 Corinthians, remember that bit from last week where Paul calls the church the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Corinthians 3:16). He uses a Greek word for house in this bit where he says God dwells with us; it is maybe more literally translated inhabits; God’s Spirit inhabits the church; and this word, it is all through 1 Timothy; where Paul is writing to his true son in the faith (1 Timothy 1:2). Paul is Timothy’s spiritual dad. We do not know what has happened to Timothy’s biological dad — he is not described as a spiritual influence when Paul reflects on the role Timothy’s mum and grandma played in teaching him God’s word (2 Timothy 1:5).

Anyway, in Paul’s opening words there is a household reference we lose in english that shapes the whole letter. Here in this warning about avoiding faithless controversies that get in the way of advancing God’s work (1 Timothy 1:4), is actually this same house word; oikos — “managing God’s work” is oikos nomia; the Greek word we get economy from; it is the idea of household management. Paul is writing to Timothy — his spiritual son — about building God’s economy; his household, which is what he calls the church.

And, up front, the goal of his instructions — the task of stewarding God’s household — is love (1 Timothy 1:5). Love from a pure heart; a good conscience and a sincere faith — you might summarise that as a transformed mind — this is a particular kind of love too — it is the word for committed, sacrificial, connected love for another person; it is about giving, not getting.

So Paul’s point in writing the instructions for what kind of examples should shape the church — spiritual parents in the household of God — is part of this guide to love; to the sort of conduct that happens — the practices — that produce the character of the household of God (1 Timothy 3:14-15). Paul gives a list of behaviours for men and women who are going to be model parents in a church community — parents who do not follow worldly patterns. In the Roman Empire in the first century there were patterns and expectations for a male head of a household; a patriarch.

Paul subverts a bunch of these as he writes to men who occupy this sort of presumed role about shaping a new type of household by not acting this way; he says these spiritual dads should be above reproach — exemplary — faithful to his wife — not engaging in the predatory sexual power games of the culture, he is to be self-controlled — not violent or striking out in anger like a Roman patriarch could when they felt wronged; hospitable — able to teach — picture taking on apprentices here, rather than just lecturing… someone who is not ruled by alcohol or money or their passions (1 Timothy 3:2-3)… someone already doing this job in their family (1 Timothy 3:4). Again — this is the same house word in Greek — it is not just about the nuclear family; though it mentions his children — a Roman household was a little economic unit; home to multiple generations, single friends and relatives — and often slaves or clients — he has got to be running his little economy — in a manner worthy of respect, of imitation — before he can be an example; a spiritual parent, an economic model in God’s household (1 Timothy 3:5).

This is true for any of the examples Paul uses in the letter; if they are not modelling it in their own households they cannot be models in God’s household (1 Timothy 3:12).

There are not just instructions about exemplary men in this letter — or this passage — some of this feels pretty gendered to us, but I reckon Paul is inverting certain stereotypes that are documented as part of Roman culture — in a patriarchal culture, not universal gender norms — and the idea is really that both exemplary men and women are worthy of respect; and — I reckon this word should actually be translated wives (1 Timothy 3:11) — Paul is mapping out the patterns of matriarchs and patriarchs — patterns — in this new household of connected love — not the self-seeking competition and power in other economies. This is not to say unmarried people cannot be heads of households, or examples to follow — as we will see…

If we flip over a few pages in 1 Timothy, in chapter 5 Paul keeps unpacking the dynamics of this new family system — Timothy is to see those he is in community with as family — older men as fathers; younger men as brothers, older women as mothers and younger women as sisters — with purity — the sort of love that comes from a pure heart (1 Timothy 5:1-2); and this pattern spreads through the community in particular ways — families care for each other — especially when suffering occurs — so we get these instructions for how to care for those within biological families, and without a biological family (1 Timothy 5:4). Kids and grandkids should care for widowed mums and grandmas — practicing our religion — that is another habit word — by caring for those in our immediate household; our families; recognising they have cared for us — this is tricky if they have not; if our family have harmed us and not loved us in ways where this care would be an act of reciprocity — and we will talk more about this; it is a challenge in the face of broken family relationships and trauma and abuse to practice our faith this way — but, just notice — and this is important — Paul has very harsh words for those who fail to care for their relatives — including parents who do not care for, or abuse, their kids — they have denied the faith and are worse than an unbeliever (1 Timothy 5:8); they have put themselves outside this network of connected love; God’s economy; the task of loving people into the love and likeness of Jesus.

Where people in the church community do not have others to care for them — where these households have failed — the church family is their household.

There is a widows list (1 Timothy 5:9-10), where the church will pay exemplary women to keep being motherly or grandmotherly examples in the life of the church — those known for their good deeds; there are big overlaps between the women provided for in these ways and men who are held up as leaders of the church — raising children… showing hospitality… serving others (1 Timothy 5:10)… while younger widows can provide for themselves — whether that is through marriage if that is an option — or through managing their own households (1 Timothy 5:14) — a type of leadership — being exemplary motherly types who care for others, presumably to cultivate this same way of life.

All of this is about the household of God; this new family that we are brought into as God makes his home among us and builds us to be his household (1 Timothy 3:14-15); his children in the world as we learn how we ought to live from people doing it; people embodying godliness — finding it expressed in the foundation of the house — the source of true godliness — Jesus — who appeared in flesh, was vindicated by the Spirit in his teaching and life and resurrection — was taken up in glory and who now forms the basis of our faith and practice; shaping our economy (1 Timothy 3:16).

So what has this letter to Timothy got to do with us — you are not an apprentice or adopted son of the Apostle Paul — but Timothy is an example for the church to imitate; a model for us — that is a lot of pressure for a young bloke — and Paul says “do not let anyone judge you for being young — focus on being an example in speech, in conduct, in love, in faith and in purity” (1 Timothy 4:12) — a picture of life in the household of God; the life of love the letter is designed to produce — this comes through devotion to reading the Scriptures (1 Timothy 4:13). Timothy is to keep the message of Jesus at the heart of the household — but not only this; he has also got to live it; his example; his progress — his growth in maturity — is to be visible to all; we are all learning what it means to grow up and mature in God’s household together — even our leaders — Timothy is to keep his life aligning with his doctrine (1 Timothy 4:15-16). Because this is the pattern we are growing into; our examples and communities form us as children of God.

While perfect habitat will not perfect our heart — that is page 2 of the Bible — our habits, our households are either part of the conforming patterns of the world, or, in the household of God, part of the transforming and renewing of our minds as God’s Spirit makes his home in us. We will be shaped by the household we belong to. To inhabit the world is to be formed by life in a household; the architectures and rhythms and examples of who we live with and where we live — or who we do not live with when we feel disconnected from others.

One of the obvious ways we inhabit time and space is by being born into a family — a household with a story or history — every human has to navigate this reality — whether our parents, or households, aid us or hinder us in seeking God. Someone born into a household in ancient Athens would be shaped not just by the architecture of the city, with its idols and temples, but the architecture of their household — their family gods — shaping their lives too. And this is true for us, and our patterns of worship.

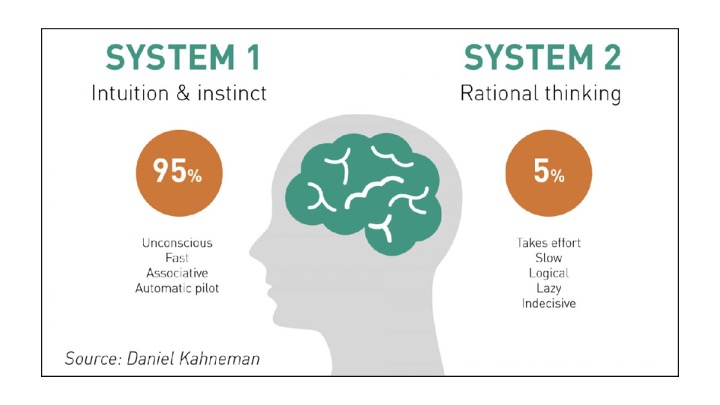

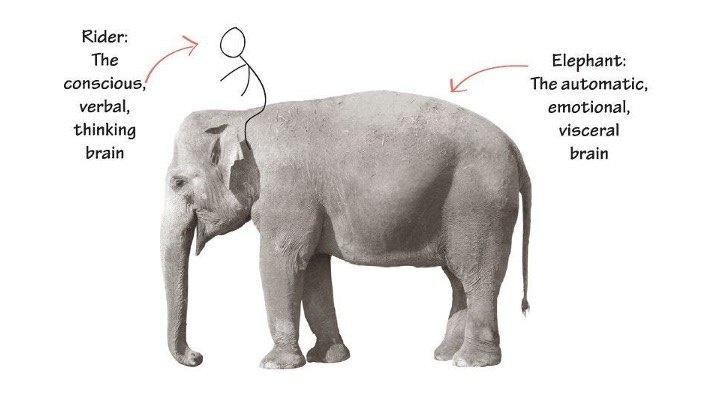

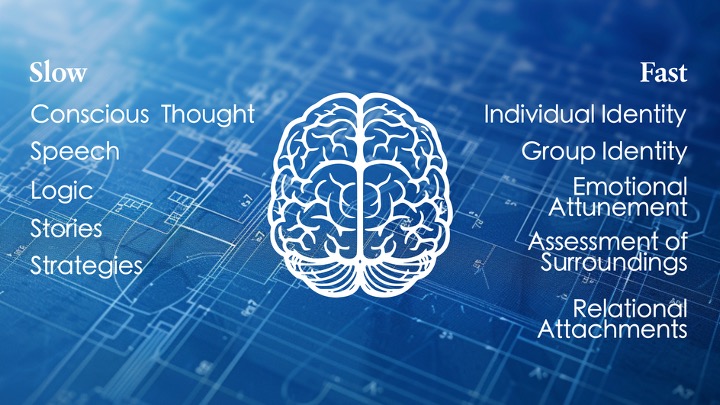

The household we are brought into profoundly shapes our elephants — more than the city; the world around us — we have been thinking about our minds — what we carry into the world using this metaphor of the rider — our thinking brains — and the elephants — our ingrained intuitive responses to the world. That part of our mind is profoundly developed — whether positively or negatively — whether through presence or absence — by those humans who shaped us; and can be reshaped by a new household built around habits of love and connection.

I mentioned Jonathan Haidt’s idea of the brain featuring a ‘rider’ and an elephant, and this book The Other Half of Church in chapter one — which is about how we are not formed just by teaching the rider; the bit of our brain shaped by listening to sermons and talking about stuff; we need to form the bit of our brain that does the heavy lifting; the automatic, intuitive bit that accounts for most of our behaviour.

The authors suggest this ‘fast’ part, or ‘elephant’ comes from who we are; who we have learned to be in our connected or disconnected relationships; this formation begins in our families as babies and infants — but it keeps happening in our bodies as we experience all the way into adulthood; we do not stop being children; we do not stop being shaped by our households. Even in my 40s I am learning that I am a child; a child of my parents; a product of my family system, my household — even as I parent my own children — I just need to keep learning to be a child of God.

My parents were pretty good, really — I have had to re-narrate the closed door and a bunch of other stuff as I have found out how hard parenting is… but there are things I want to do differently as I set an example for others — including my kids — new patterns to learn — and I know that for some of us this is a bigger battle, because the patterns of our families have traumatised us; leaving our elephants scared and scarred. Trauma shapes our elephant; this part of our brains — because trauma is a function of broken relationships; not having a secure way to process suffering.

Humans need a household — whether that is biological or not; the households we define ourselves around — and their rhythms and our experience of embodied life within them — produce our character, shaping our hearts and minds. Children of God need households operating according to the values and conduct of the household of God; his economy, where spiritual parents provide examples of maturity and love for us in secure and connected relationships; love that reflects God’s love. If you are a parent who wants your kids to know the love of Jesus — whether they are infants or adults — you might need to assess where your spiritual parenting is forming those in your household — including you — are you conforming to the patterns of this world, or being transformed by God’s Spirit dwelling among you? What are your routines — when you get up in the morning is it the “get out the door” rush that teaches work and school and success are important — or connection to each other and to your heavenly Father that guides your steps? What do you talk about together? When do your kids experience encouragement and connection? When you discipline are you discipling?

I know I have got some work to do as a parent on this front. I have still got things to learn and unlearn from my own parents, and from other spiritual parents in our community. And I need help. But I grew up in a household that wanted this for me.

If your biological parents have been abusive or harmful — worse than unbelievers — you might — even as an adult — need spiritual parents, in a community lovingly teach you a new way of life as you submit to learning their example rather than imitating or reacting against those who harmed you. Family trauma — broken attachments — not being cared for — stops us growing up because the people who were meant to model these things have failed us. When we are in this situation we need a new household. New models.

Lots of people who have experienced trauma or exclusion from their biological families have created new household structures — using language like “chosen families” — which is great — but often these chosen families are peer networks, often with others who have experienced similar patterns, with an inbuilt suspicion — and trauma response triggered by parent-like figures. I wonder if we do not just need chosen families but chosen parents; those in the household of God who can teach and model life in God’s family for us — and — perhaps — actually start undoing some of the ways we have been harmed. And there is a role here in our community for some of you older folks — or us older folks — to serve as chosen parents or grandparents in the faith. If you are older you might need to take steps to build some of these connections with others, while if you are younger you might need to deliberately ask some older folks to be part of your life; to open their households to include you. Growth groups are part of that in the rhythms of our church family.

I mentioned this book The Common Rule, in chapter one, and this quote from Justin Earley about “the house of his life” being decorated with Christian content while the architecture of his habits was like everyone else’s.

“While the house of my life was decorated with Christian content, the architecture of my habits was just like everyone else’s.”

And because I would like to make changes on this front for me, and for my household, I was excited to read his follow up, called Habits of the Household — it is another book full of quotable quotes and ideas of practices and rhythms to build into home life.

He seems to be zeroing in on 1 Timothy when he says our households should be little schools of love; habitats that teach inhabitants to live our calling; to be formed as lovers of God and neighbour.

“The most Christian way to think about our households is that they are little ‘schools of love’… places where we have one vocation, one calling: to form all who live here into lovers of God and neighbour.” — Justin Whitmel Earley, Habits of the Household

He chose the word “household” not “family” because he reckons we should think bigger than the nuclear family…

“Thinking in terms of the household, instead of just the family unit, encourages us to think bigger about how God is working through our families… People do not join our households just because you wish for them to. They become part of the household because there is a rhythm or a pattern that invites them in.”

But apart from his chapter on hospitality, which imagines making ways for others to become part of the household at the table, his book is really about the nuclear family… and about parenting.

It was disappointing — the households of the first century; multi-generational groups of connected people — not just biologically related to one another — were a brilliant structure, and as we have reduced life to biological families living disconnected lives in the modern world we have created all sorts of problems for ourselves; especially when it comes to learning to be human and the pressure placed on parents, and kids. And plenty of households in church communities are not nuclear families with two parents.

There are some helpful practices in the book that can be applied in various contexts, but if we see the church as the household of God — made up of households — and that this might happen in chosen family groups, and different structures — not just biological families — then I reckon it is worth engaging with The Other Half of Church — and, for homework, I would love you to read it, or listen to The Other Half of Church podcast — especially the episodes on joy and hesed. Hesed is the Hebrew word for connected, committed love — in Greek it is translated into ‘agape,’ the love Paul says is the goal in God’s household.

The writers of this book are incorporating the work of modern psychologists like Allan Schore — I read some of his work this week and he seems legit — his work on attachment theory is built on the idea that we develop attachment through our eyes and our faces — especially through experiencing joy; connection to a person looking at us who is glad to be with us — an open door.

“If Dr Schore is right about the definition of joy being what I feel when I see the sparkle in someone’s eye that conveys ‘I am happy to be with you,’ I was experiencing joy… Our identity is built and formed by joy-bonded relationships. The identity center in our brain grows in response to joy.”

— The Other Half of Church

This is identity-shaping; elephant-shaping… so much of my parenting has communicated the opposite — especially when I have been working on the couch and been annoyed by an interruption; gazing at screens does the opposite — anyway, they reckon our identity; our right-brained sense of self is formed by joy-bonded relationships — they build on this idea that biblically, joy is connected to God’s face shining upon us — and that we experience this in face-to-face community aimed towards this sort of connection — and where churches do not habitually express and include this joy face to face, eye to eye — our ability to produce fruitful life is depleted — they use the analogy of cultivating the right sort of soil to grow towards maturity.

“If my community is not in the habit of expressing what God sees as special in each of us, our eyes do not meet and our faces do not shine when we see each other. Our soil becomes depleted. Soil that is low on joy is primed for growing addictions. When our brain looks for joy and does not find it, we become vulnerable to ‘pseudo-joys.’”

— The Other Half of Church

Where we do not have this joy we start looking for it in pseudo-joys — addictions; things like consuming; looking at people’s faces on social media; porn; the stuff in the list of behaviours that spiritual parents in God’s household should model avoiding. They reckon we need to practice face-to-face “joy transmission” in our households.

“If joy is transmitted primarily through our faces and eyes, we need to practice letting our faces light up with each other… Our brains draw life from our strongest relational attachments to grow our character and develop our identity. Who we love shapes who we are.”

— The Other Half of Church

We share in communion as a community; a household — connected by bonds of love; by God’s love — his Spirit dwelling in us — inviting us to be at home with him as his household. The people around you as you take communion are prime candidates to be this household for you — a community we are attached to, where we experience hesed — this love — God’s love.

Our elephants are formed by the joy we experience in strong relational attachments — who we love shapes who we are. This is true of our attachment to God, but we learn this from each other as we take up the task of forming one another towards maturity; listening to the word of God and taking on the character of Jesus; the source of godliness — and we only do this when we build our community wanting this attachment with each other, where we experience a different economy; one not built on consumption or self-service, but on connected love where we come face to face not just with people glad to be with us, but the God who adopts us into his family.