“People need to realise it doesn’t matter what living meat skeleton you’re born into; it’s what you feel that defines you.” — Victor (in the video below)

This is Victor. Victor identifies as non-binary, and this BBC video features Victor explaining a little bit of life from a non-binary perspective. It did the rounds on social media recently. It’s an interesting and increasingly common account for what it means to be human. Victor’s account of what it means to be human is this: you are a feeling mind with a meat skeleton; but the real you is the ‘feeling mind’ part — your consciousness — and your body might get in the way. If that happens then feelings (your choice) trump meat (an unchosen thing you’re born with).

It’s true that we are both mind and body, maybe even ‘soul’ and body… and our accounts of what it mean to be human need to reconcile these two realities in a way that helps us make sense of our experience of the world, and in a way that helps us figure out what to do when our bodies and minds seem to be in conflict.

One of the things I’ve spent this year reading about, thinking about, and writing about is how Christians can respond with love and understanding to the growing conversation about gender identity and gender fluidity. A paper our Gospel In Society Today committee (a thing I’m on for the Presbyterian Church of Queensland) has put together on this issue will be released soonish, but this video was one of the stranger and more worrying parts of what is a complicated issue where one’s gender identity is not necessarily as simple as a binary view of either physical sex and gender makes out. Being human is not quite as simple as Victor suggests. Extrapolating an understanding of humanity and what a flourishing human life looks like — what shape our identity takes — from the experience and feelings of particular individuals (or any individuals) is not a great way to do anything (this is also true from the direction of ‘cis-gendered’ people backwards too, where ‘cis’ is a pre-fix for those whose physical sex and gender identities line up). We often have a tendency when dealing with the complexity of human existence to assume our experience is both normal and should be ‘the norm’ and that’s dangerous.

The view of what it means to be human that Victor in this video puts forward is an unfortunate extrapolation from the real felt experience of the few to the many. Your body isn’t just a ‘meat skeleton’ with the real you somehow immaterially enshrined in this skeleton; you are your body. There’s something a bit appealing to this idea, not just as it applies to the gender conversation but because our bodies are limiting when it comes to what we imagine flourishing to look like. I want to be healthy and fit; but my body lets me down in that I get sick and injured. I want to be able to go wherever I want, whenever I want, but my body can only occupy one place at any given moment, and my moments are limited. I want to be immortal, but my body is on the timeline to decay. I do want to be able to escape the constraints of my body; humans yearn for that; particularly we want to escape from the bits of our bodies that are broken and dying. It’s nice to believe that our minds are somehow the real us; that the real us doesn’t decay, disappoint, or die; it’d be nice if our bodies were just meat skeletons that we could augment or change based simply on how we feel without that impacting ‘the real us’ (except as we bring them in line with the real us).

But this idea that we’re just our ‘feelings’… that our bodies don’t really matter… This is the gnostic heresy of the secular age. And it’s not necessarily a great ‘secular’ solution to issues like gender dysphoria or gender identity either (though solutions that don’t deal with us as ’embodied beings,’ the idea that our bodies are able to be ‘unbroken’ via our minds, or that someone can simply ‘think themselves’ into a solution aren’t very useful either, but that’s a rabbit hole for another time). Victor also assumes a radical disconnection between our bodily experience and our minds that doesn’t seem to stack up with modern neuroscience (which suggests what we do with our bodies impacts our minds) either, but again, that’s another rabbit hole.

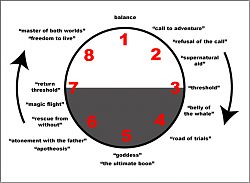

The secular age is a label philosopher Charles Taylor uses to describe our current western world’s grand organising narrative; its ‘myths’; its account for what human life is; and thus what a flourishing life looks like. The secular age involves the death of the soul as a concept, because it involves switching a view of the world where both the spiritual (or transcendent) and material (or immanent) are real and important for a world where only the material matters. This leaves us with an interesting account of our human experience and what it means to be really human. Our new post-soul way of understanding the world from this immanent viewpoint replaces the ‘soul’ with the mind. We now see ourselves as immanent creatures and any gap, or conflict, between mind and matter in our experience will be left for us to figure out as we come up with a story that explains how to be human. In this video with Victor it seems this movement involves creating a new duality between mind and matter — or your feelings and your body (how you feel things apart from your senses and the chemical make-up of your brain (and how that might be influenced by the activities of your body) is something not totally fleshed out in Victor’s anthropology). Victor’s story is a story like this; in Victor’s account human history has been oppressive because we’ve understood physical sex (matter) and gender (mind) as being things that are best held together; or understood as being a single thing when real enlightenment allows us to see them as they truly are — different — so that true freedom is somehow found in transcending our ‘matter’ so that our sense of ourselves is found in our mind. Only, because the transcendent no longer exists as a spiritual account of reality that overlapped the material so that both were true and held in tension; this transcendence comes from making one part of us less meaningful as we make the other bit more meaningful. Victor sees the material and the mind being, at times, in competition, and as a result says “you are defined by what you feel.”

Gnosticism was an early Christian heresy built from Plato’s understanding of reality. Plato taught there is a ‘spiritual’ world of ‘ideals’ and a ‘material’ world of ‘forms’ and the truest reality is the spiritual one, and the physical stuff is broken, and non-ideal, and to be transcended. Gnostics applied this to Christianity and came up with the belief that our bodies are utterly broken and sinful and awful and dirty and to be transcended. It taught that you were a soul; and that you were lumped with a body. The soul trumped the body. The body was a meat skeleton to be escaped from.

It’s the same story Victor is telling; this idea that you’re much more than a meat skeleton, if you’re even a meat skeleton at all. This ‘meat skeleton’ phrase reminds me of a couple of passages from three of my favourite ‘secular’ stories by three secular age writers; William Gibson, Kurt Vonnegut, and David Foster Wallace.

William Gibson’s Neuromancer which explores what might happen if we rely on technology to replace the transcendent. In Neuromancer you can get a chip implanted in your head that allows you to jack-in to cyberspace so that your body exists in the physical world (meatspace) while your mind is in cyberspace. Prostitutes in this world can hire out their bodies while their minds are occupied in the cyber world; so they’re called ‘meat puppets’… which isn’t so different from Victor’s ‘meat-skeleton’ only in Victor’s account your mind is the puppeteer, in control of your meat, not someone else. Case, the protaganist, was a cyber-cowboy (a hacker) who lost his ability to be part of cyber-space but is given it back in order to complete a big hack; he’s torn between two worlds; two realities; the transcendent reality of cyber-space and the physicality of meat-space; without spoiling things too much this para is from near the end of the book:

“No,’ he said, and then it no longer mattered, what he knew, tasting the salt of her mouth where tears had dried. There was a strength that ran in her, something he’d known in Night City and held there, been held by it, held for a while away from time and death, from the relentless Street that hunted them all. It was a place he’d known before; not everyone could take him there, and somehow he always managed to forget it. Something he’d found and lost so many times. It belonged, he knew – he remembered – as she pulled him down, to the meat, the flesh the cowboys mocked. It was a vast thing, beyond knowing, a sea of information coded in spiral and pheromone, infinite intricacy that only the body, in its strong and blind way, could ever read.” — Neuromancer

Somehow Gibson is convinced that the body matters. Kurt Vonnegut explores the idea that we’re both ‘meat’ and ‘soul’, and that the key to happiness (and to seeing others properly) is about understanding each, then aligning them, in his novel Bluebeard. The main character, artist Rabo Karabekian, moves from this almost gnostic belief that they’re separate and irreconcilable; but that the soul is the true self to something that sees them as working together. So there’s this dialogue, where :

“I can’t help it,” I said. “My soul knows my meat is doing bad things, and is embarrassed. But my meat just keeps right on doing bad, dumb things.”

“Your what and your what?” he said.

“My soul and my meat,” I said.

“They’re separate?” he said.

“I sure hope they are,” I said. I laughed. “I would hate to be responsible for what my meat does.”

I told him, only half joking, about how I imagined the soul of each person, myself included, as being a sort of flexible neon tube inside. All the tube could do was receive news about what was happening with the meat, over which it had no control.

‘”So when people I like do something terrible,” I said, “I just flense them and forgive them.”

“Flense?” he said. “What’s flense?”

“It’s what whalers used to do to whale carcasses when they got them on board,” I said. “They would strip off their skin and blubber and meat right down to the skeleton. I do that in my head to people—get rid of all the meat so I can see nothing but their souls. Then I forgive them.”

At this point Rabo is operating with the belief that the soul is the ‘true’ self and the meat gets in the way… but he’s brought back to reality (or to real reality) in the closing words of the book; when he’s forced to see that when he makes art it’s actually his soul and meat working together (in a passage where the critique of trying to hold body and soul apart is a bit similar to some stuff Irenaeus wrote against the Gnostics in the second century). His art studio is a potato barn.

”Your meat made the picture in the potato barn,” she said.

“Sounds right, “ I said. “My soul didn’t know what kind of picture to paint, but my meat sure did.”

“Well then,” she said, “isn’t it time for your soul, which has been ashamed of your meat for so long, to thank your meat for finally doing something wonderful?”

I thought that over. “That sounds right too,” I said.

“You have to actually do it,” she said.

“How?” I said.

“Hold your hand in front of your eye,” she said, “ and look at those strange and clever animals with love and gratitude, and tell them out loud: ‘Thank you, Meat.’”

So I did.

I held my hands in front of my eyes, and I said out loud and with all my heart: ‘Thank you, Meat.’”

Oh happy Meat. Oh happy Soul. Oh happy Rabo Karabekian.

David Foster Wallace explores the relationship between the body and something more than the body at the heart of our humanity through the lens of learning to play tennis in both his celebrated essay on Roger Federer published as “Roger Federer as Religious Experience” in the New York Times (but as the title essay Both Flesh and Not in that collection of his articles and essays), and in his novel Infinite Jest which features a tennis playing prodigy as one of the protaganists. Wallace was, himself, a competitive junior tennis player so you sense that some of his insights into what it means to be meat are autobiographical; what’s a bit different is that Wallace seems to assume that you are first your physical body; that meat matters, and even that anything more that is out there is fed and cultivated by what we do with our ‘meat’… what we give ourselves to. With tennis as a bit of a metaphor for the life well lived, he explores the idea that transcendence is found by pushing our well-trained muscle-memoried bodies to new heights via the imagination; our bodies somehow show our minds what is possible because they act as some sort of sub-conscious us.

“Tennis’s beauty’s infinite roots are self-competitive. You compete with your own limits to transcend the self in imagination and execution. Disappear inside the game: break through limits: transcend: improve: win. Which is why tennis is an essentially tragic enterprise, to improve and grow as a serious junior, with ambitions. You seek to vanquish and transcend the limited self whose limits make the game possible in the first place.” — Infinite Jest

Then when Hal, the tennis prodigy, is being coached. His coach says the key to a sort of ‘flourishing humanity’ starts with our ‘meat’; that we’re meat first:

“‘Boys, what it is is I’ll tell you it’s repetition. First last always. It’s hearing the same motivational stuff over and over till sheer repetitive weight makes it sink down into the gut. It’s making the same pivots and lunges and strokes over and over and over again, at you boys’s age it’s reps for their own sake, putting results on the back burner, why they never give anybody the boot for insufficient progress under fourteen, it’s repetitive movements and motions for their own sake, over and over until the accretive weight of the reps sinks the movements themselves down under your like consciousness into the more nether regions, through repetition they sink and soak into the hardware, the C.P.S. The machine-language. The autonomical part that makes you breathe and sweat. It’s no accident they say you Eat, Sleep, Breathe tennis here. These are autonomical. Accretive means accumulating, through sheer mindless repeated motions. The machine-language of the muscles. Until you can do it without thinking about it, play… The point of repetition is there is no point. Wait until it soaks into the hardware and then see the way this frees up your head. A whole shitload of head-space you don’t need for the mechanics anymore, after they’ve sunk in. Now the mechanics are wired in. Hardwired in. This frees the head in the remarkablest ways. Just wait. You start thinking a whole different way now, playing. The court might as well be inside you. The ball stops being a ball. The ball starts being something that you just know ought to be in the air, spinning. This is when they start getting on you about concentration. Right now of course you have to concentrate, there’s no choice, it’s not wired down into the language yet, you have to think about it every time you do it. But wait till fourteen or fifteen. Then they see you as being at one of the like crucial plateaus. Fifteen, tops. Then the concentration and character shit starts. Then they really come after you. This is the crucial plateau where character starts to matter. Focus, self-consciousness, the chattering head, the cackling voices, the choking-issue, fear versus whatever isn’t fear, self-image, doubts, reluctances, little tight-lipped cold-footed men inside your mind, cackling about fear and doubt, chinks in the mental armor. Now these start to matter. Thirteen at the earliest. Staff looks at a range of thirteen to fifteen. Also the age of manhood-rituals in various cultures. Think about it. Until then, repetition. Until then you might as well be machines, here, is their view. You’re just going through the motions. Think about the phrase: Going Through The Motions. Wiring them into the motherboard. You guys don’t know how good you’ve got it right now.” — Infinite Jest

One of the more powerful things about Infinite Jest is that it explores how the addictions that shape our bodies ultimately shape our humanity; and this sort of tennis training is a sort of ‘rightly directed’ addiction (or is it); it seems better than being addicted to drugs or entertainment… two of the other pictures of meat-shaping (or miss-shaping) habits in the novel.

Somehow, for Wallace, we are inextricably embodied; our meat matters because it shapes everything else about who we are and how we flourish; and when we’re ultimately flourishing it’s because our meat and our minds are meeting; intuitively. When everything comes together in this tennis-as-a-metaphor-for-life thing we no longer notice the ‘dual’ reality.

You’re barely aware you’re doing it. Your body’s doing it for you and the court and Game’s doing it for your body. You’re barely involved. It’s magic, boy. — Infinite Jest

And in a moment on the court where things go wrong; when one’s body betrays you and you slip and fall… that’s when we know that our meat matters; that it’s not something to be left behind when we achieve these magical, transcendent, moments, but part of those moments.

It was a religious moment. I learned what it means to be a body, Jim, just meat wrapped in a sort of flimsy nylon stocking, son, as I fell kneeling and slid toward the stretched net, myself seen by me, frame by frame, torn open. — Infinite Jest

For Wallace our bodies, our ‘meat skeletons’, are actually the key to transcendence; not in departure from them but in that they are the key to truly understanding ourselves. He returns to tennis as a lens for that in his Federer essay, where he explores the idea that watching a tennis player who has achieved the sort of bodily self-mastery described in the novel is actually a religious experience as much as the one that he describes in the injury-inducing slip above, but in the opposite direction. We touch something radically true about ourselves when our bodies are vehicles for something more than just ‘the physical’; when our bodies and souls are in sync.

“Beauty is not the goal of competitive sports, but high-level sports are a prime venue for the expression of human beauty. The human beauty we’re talking about here is beauty of a particular type; it might be called kinetic beauty. Its power and appeal are universal. It has nothing to do with sex or cultural norms. What it seems to have to do with, really, is human beings’ reconciliation with the fact of having a body.” — Both Flesh and Not

In the footnotes he gives us this exploration of this embodied understanding of our humanity.

There’s a great deal that’s bad about having a body. If this is not so obviously true that no one needs examples, we can just quickly mention pain, sores, odors, nausea, aging, gravity, sepsis, clumsiness, illness, limits — every last schism between our physical wills and our actual capacities. Can anyone doubt we need help being reconciled? Crave it? It’s your body that dies, after all.

There are wonderful things about having a body, too, obviously — it’s just that these things are much harder to feel and appreciate in real time. Rather like certain kinds of rare, peak-type sensuous epiphanies (“I’m so glad I have eyes to see this sunrise!,” etc.), great athletes seem to catalyze our awareness of how glorious it is to touch and perceive, move through space, interact with matter. Granted, what great athletes can do with their bodies are things that the rest of us can only dream of. But these dreams are important — they make up for a lot. — Both Flesh and Not

This sort of ‘reconciliation’ he’s talking about is the realisation that we’re not simply minds who have meat attached; but rather that our bodies are inevitably part of our humanity (and part of the limits of our humanity in this secular age), and the best vision of human flourishing he can arrive at from that point is not that real flourishing is about detachment from the body, but rather the body and soul working together to make beautiful tennis. Even if those moments are only fleeting and finite.

Genius is not replicable. Inspiration, though, is contagious, and multiform — and even just to see, close up, power and aggression made vulnerable to beauty is to feel inspired and (in a fleeting, mortal way) reconciled. — Both Flesh and Not

For Wallace, watching peak-Federer was a vision of the best that could be achieved in our material world; and hinted at something more. Wallace, more than any other secular age writer, was haunted by ‘the gnawing sense of having had and lost some infinite thing’ (as he put it in This Is Water). Somehow, in Federer and his embodiment (and go read the essay) he finds some sort of solace when it comes to questions of bodily malfunctions, like those we’re confronted with in a broken world filled with broken bodies, like the kid with cancer who tossed the coin in the match he’s writing about, somehow this glimpse of transcendence through the body working in sync with the ‘soul’ and flourishing, somehow that helps Wallace understand what being human; body, mind, and soul, looks like. And it doesn’t come from transcending your ‘meat’ but achieving some sort of transcendence ‘as meat’…

“[Federer] looks like what he may well (I think) be: a creature whose body is both flesh and, somehow, light.” — Both Flesh and Not

These writers offer a nice ‘secular’ critique of Victor’s belief that we’re minds who need to transcend our meat skeletons. But the Christmas story is an even better critique; and one that affirms the good and true things Gibson, Vonnegut and Wallace are grasping for as they affirm the importance of our ‘meatiness’.

Christmas (and Irenaeus) as the answer to this modern ‘gnostic’ dilemma

The Christmas story is fundamentally the story of God meeting us in our meatiness… in meatspace… to provide this sort of ‘reconciliation’ between body and soul, and between the transcendent and immanent; this isn’t just ‘reconciliation’ in the David Foster Wallace sense of those fleeting moments in this world where things feel right; but a permanent fix that means that feeling isn’t just fleeting. It’s the sort of change that brings the transcendent, supernatural, ‘soul’ reality and the immanent natural material world of our bodies back into harmony in a way that deals with both our impending meaty death, and the ‘gnawing sense’ of having lost the infinite.

The Christmas story was the answer to old fashioned gnosticism; and is the answer to the fears of the secular age and its searching for a way to make sense of our ‘meat’ and our feelings in some sort of ‘reconciled’ order.

The Christmas story, what Christians call ‘the incarnation’ — where the divine ‘word of God’, Jesus, a person of the Trinity, permanently takes on human flesh — has always been the answer to gnostic tendencies; to our desire to find some key to escape the limits of our dying bodies.

The Christmas story — the story at the heart of Christianity; and indeed the heart of what Christians believe it means to be human and to flourish is a radical critique of both gnosticism and this new ‘mind over matter’ vision of the human body as a ‘meat skeleton’ to transcend.

The Christmas story teaches us that to be truly human is to have a body, and a soul. In the Christmas story we meet the truest human. You’re not just a soul with a body either; despite that apocryphal quote reputedly from C.S Lewis. You’re both. Paradoxically. Always.

The Easter story promises us that one day all our Christmases will come at once and our bodies will be made new, reconciled, and paired perfectly, with our souls. We’ll be flesh and light. And we get a taste of that now as we live out, and live in, the story of Jesus. This is the promise of the Christian story, one Paul writes about in 1 Corinthians 15.

“The first man Adam became a living being”; the last Adam, a life-giving spirit. The spiritual did not come first, but the natural, and after that the spiritual. The first man was of the dust of the earth; the second man is of heaven. As was the earthly man, so are those who are of the earth; and as is the heavenly man, so also are those who are of heaven. And just as we have borne the image of the earthly man, so shall we bear the image of the heavenly man.” — 1 Corinthians 15:46-49

This isn’t to disparage our human bodies and the reality of life where our souls and bodies feel conflicted; but to point us to where real reconciliation is found; it’s in the death of death and in our bodies and souls being joined in an imperishable and harmonious way that lines up with the ‘heavenly man’; the one born as a meaty human at Christmas, and raised as a meaty human at Easter.

Gnosticism is actually pretty terrible news for us as humans; it leads to all sorts of awful self-hatred because being ‘meat’ is actually fundamental to our experience of the world and our ability to know things. It’s soul crushing even in its attempt to free us to simply ‘be a soul’… it isn’t a particularly helpful or possible vision of human flourishing whether it’s being pushed by Plato, or the gnostics of the early church (who denied the incarnation because their vision of God wouldn’t be caught dead in a dirty human body), or a modern day ‘non-binary’ philosopher like Victor. We can’t simply escape our bodies or pretend we are something other than our flesh, because we are actually ‘both flesh and not’…

There are very good reasons that gnosticism was viewed as a heresy; it’s actually the same reason that for many years the pre-secular age western world has seen our physical reality and a more transcendent reality both being parts of being truly human. It’s a very good reason it hasn’t been understood as being ‘oppressive’ to link our physical sex with our gender (even if our physical sex is sometimes non-binary, and some individuals do experience gender as less binary than we might). To be human was to be both body and soul; not just a soul with a body. The answer to the experience of individuals with non-binary sex or gender is not to ‘reconcile’ this divide by simply dismissing our bodies as meat to be transcended (or ignored); but rather to hope for soul and body to be brought back together; for those Federer-like moments to be permanent. This was the hope Irenaeus, a guy who wrote Against Heresies as the most substantive critique of gnosticism relied on in countering the belief that the human task was for the soul to leave the dirty body behind.

Irenaeus understood the present human condition as being one where our souls and bodies are ‘separate’ and where our impending death (and constant decay) are part of what creates this divide. His hope was for ‘recapitulation’ or a ‘re-creation’ — an intervention by God to address this divide so that our souls eventually find their right home in a re-created immortal body (Against Heresies Book 2 Chapter 34). We don’t reconcile this separation by denying the reality of body, or soul (or feelings), but by hoping for this re-aligning of the two where the alignment has been affected in our broken world, and the key to this reconciliation is not our own self-mastery of our bodies ala Wallace’s Federer, but the master of body and soul, the maker of our bodies and souls, meeting us in meat space and providing a path to reconciliation with the divine life. That’s the Gospel story; the Christmas story; the story that speaks into what it means to be truly human (even if this all sounds like some weird wizardry or hocus-pocus in our secular age). This was a story the western world took very seriously in understanding what it means to be human for a very long time.

For it was for this end that the Word of God was made man, and He who was the Son of God became the Son of man, that man, having been taken into the Word, and receiving the adoption, might become the son of God. For by no other means could we have attained to incorruptibility and immortality, unless we had been united to incorruptibility and immortality. But how could we be joined to incorruptibility and immortality, unless, first, incorruptibility and immortality had become that which we also are, so that the corruptible might be swallowed up by incorruptibility, and the mortal by immortality, that we might receive the adoption of sons? — Irenaeus, Against Heresies Book 3 Chapter 19

Since the Lord thus has redeemed us through His own blood, giving His soul for our souls, and His flesh for our flesh, and has also poured out the Spirit of the Father for the union and communion of God and man, imparting indeed God to men by means of the Spirit, and, on the other hand, attaching man to God by His own incarnation, and bestowing upon us at His coming immortality durably and truly, by means of communion with God—all the doctrines of the heretics fall to ruin. — Irenaeus, Against Heresies Book 5 Chapter 1

Irenaeus fairly boldly declared that the Gospel story properly understood was enough to ‘ruin’ the gnostic account of humanity; and I think the Christmas story, the story of God-becoming-meat, is enough to answer Victors idea that our meat skeletons are unimportant when it comes to who we really are. You are a body. You are a soul. That these two parts of you aren’t always working in harmony doesn’t mean you need to escape your meat; it might mean that your meat and your soul need some work to reconcile them in a way that allows you to ‘flourish’…

We all feel bereft and have that ‘gnawing sense’ that these dead bodies aren’t delivering for us whether we experience that in the form of our gender not lining up with our sex, or the myriad other things that make our bodies feel like less-than-home; but for Irenaeus the answer to the gnostic desire to escape our meat was the picture of God becoming meat to meet us in our humanity and chart a way forward to our ‘meat’ being redeemed and made immortal; his hope is for the time promised by that first Christmas, when our bodies and our souls would be brought in harmony by the one who made both. Our problem is that the human default after our rejection of God’s design for us is this dying brokenness, where our souls and our matter don’t line up. Christmas, the incarnation, is the first step towards the death of death and the reconciling of our bodies and souls… it’s not tennis that gets us there; though tennis might point us there and be a taste of what’s to come.

Hope for humanity, in Irenaeus response to ancient gnosticism, in the Gospel story, and in a response to Victor’s modern attempt to free us to be truly human by separating ‘meat’ and feelings, isn’t found in departing from our meatiness, but in both being ‘reconciled’ and made new without the presence of death, decay, and disappointment. Without the sense of us not being at home in our broken and dying bodies. That’s the hope of Christmas, where the God who made us takes the first step towards having a human body broken and dying for us…

Here’s a bit more Irenaeus to plough through…

“But if the Lord became incarnate for any other order of things, and took flesh of any other substance, He has not then summed up human nature in His own person, nor in that case can He be termed flesh. For flesh has been truly made [to consist in] a transmission of that thing moulded originally from the dust. But if it had been necessary for Him to draw the material [of His body] from another substance, the Father would at the beginning have moulded the material [of flesh] from a different substance [than from what He actually did]. But now the case stands thus, that the Word has saved that which really was [created, viz.,] humanity which had perished, effecting by means of Himself that communion which should be held with it, and seeking out its salvation. But the thing which had perished possessed flesh and blood. For the Lord, taking dust from the earth, moulded man; and it was upon his behalf that all the dispensation of the Lord’s advent took place. He had Himself, therefore, flesh and blood, recapitulating in Himself not a certain other, but that original handiwork of the Father, seeking out that thing which had perished. And for this cause the apostle, in the Epistle to the Colossians, says, “And though ye were formerly alienated, and enemies to His knowledge by evil works, yet now ye have been reconciled in the body of His flesh, through His death, to present yourselves holy and chaste, and without fault in His sight.” He says, “Ye have been reconciled in the body of His flesh,” because the righteous flesh has reconciled that flesh which was being kept under bondage in sin, and brought it into friendship with God.” — Irenaeus, Against Heresies Book 5 Chapter 14