“I desired dragons with a profound desire. Of course, I in my timid body did not wish to have them in the neighbourhood, intruding into my relatively safe world, in which it was, for instance, possible to read stories in peace of mind, free from fear. But the world that contained even the imagination of Fàfnir was richer and more beautiful, at whatever cost of peril.”

Tolkien, On Fairy Stories

I’ve decided I want to be a dinosaur.

The more I watch technology be uncritically embraced — not simply by the church in Covid-19 lockdown, or even by society at large, but by myself, the more I wonder what we’re inviting into our lives in the name of progress.

I fitted multiple rooms in our house with Google Homes, and that wasn’t enough. We have Alexa devices in the kids room to read them bedtime stories. I spend hours staring at backlit black glass. I’ve been blogging for longer than I’ve been married, and on Facebook for almost as long. I registered domain names for my kids when they were born. I’m not quite a digital native, but I’m very close… I love technology. And yet. I’m convinced there’s a dark side to technology — that we become what we behold, that technology is not neutral. Marshall McLuhan once said:

“Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot.”

McLuhan, Understanding Media

Neil Postman, a student of McLuhan’s, suggested that unless we can see the impact technology has had on society and culture in the past, we shouldn’t be allowed to set rules for adopting new technologies — or to assess their potential.

“A sophisticated perspective on technological change includes one’s being skeptical of Utopian and Messianic visions drawn by those who have no sense of history or of the precarious balances on which culture depends. In fact, if it were up to me, I would forbid anyone from talking about the new information technologies unless the person can demonstrate that he or she knows something about the social and psychic effects of the alphabet, the mechanical clock, the printing press, and telegraphy. In other words, knows something about the costs of great technologies.”

Neil Postman, ‘Five Things We Need To Know About Technological Change.’

I wonder how many churches who have jumped to livestreaming broadcast media style services (rather than social media services, or gatherings) have thought about the impact the clock had on the human psyche, or the printing press (let alone the alphabet). I wonder how many people have paused before Zooming off into livestream meetings. And how many of us, then, are surprised by the developing phenomenon of ‘Zoom fatigue’ and the interesting reminders it provides, as we assess that phenomenon, that we’re actually creatures created to live in time and space, not be broken up into pixels like Mike Teavee from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory and beamed across space to be put together in tiny pieces on someone else’s screen? Curt Thompson has a great piece on how to push ourselves back into our bodies for those struggling with this phenomenon.

I’ve seen lots of conversations from church leaders about technology; what to buy, how to solve issues, how to engage those checking out your service with technological follow up… questions about technique, that all assume we’re doing what we should be doing by jumping to technology to extend us from one space to another, without asking what happens as communications technology annihilates space and time the way C.S Lewis described the car ‘annihilating space’ — and bemoaned its impact on village (and church) life as suddenly we were empowered by the choice not to go to our local church, but to find other options, including the option of not going to church at all. How much more is this true of our incredible capacity to drop in on a seemingly infinite number of churches from around the world through their digital platforms; never having to physically visit in order to consume church. And look. We don’t have much choice at the moment; technology has to be part of our solution if we want to love our neighbours and obey our government.

I read one piece that suggested churches have, or are now needing to, reinvent themselves; where once we were ‘event organisations’ suddenly we’re ‘media organisations’ — what happened to community organisations, or relationship networks, or any other descriptor that might provide a different approach to how we be the church in this time; this pivot expresses the way that we uncritically participate in what Jacques Ellul described as the technological society, where we solve problems by finding the best technique using the technological tools at our disposal; because thats’ what we think we ‘ought’ to do.

Maybe one of the things that makes me want to be a dinosaur is that I spend a significant amount of time playing the augmented reality game Jurassic World Alive, think Pokemon Go but with dinosaurs. Dinosaurs are great.

The thing about every Jurassic Park movie ever is that it explores a particular question about our relationship with technology. Sure. Dinosaurs are awesome. But just because we can do something with technology, doesn’t mean we ought, no matter how awesome we might think the results are or could be, there are always unforeseen circumstances that come from unleashing the raptors, or in the case of Jurassic Park, the T-Rex.

There’s an old fallacy — the naturalistic fallacy — that says you can’t infer an ought from an is, just because something is the way it is, doesn’t mean it ought to be that way. Think about, perhaps, a human propensity to dishonesty or violence — just because those come naturally, doesn’t mean we ought to enshrine them as virtues or the basis of our society. The technological fallacy we’re too quick to fall for in our desire to see all progress as good progress is that because we can do something with technology, we ought to. I think we’re seeing an outwork of this technology in the way the Aussie church is responding to Covid-19 with some ‘technological advances’ — just because you can bring TV style production to your church service, or make your kids church a TV show that can be watched from the lounge room at any time, doesn’t mean you ought. Just because you can create algorithms that generate a more accurate understanding of a person’s desires and behaviours than a person’s spouse has of them (and this was in 2015) doesn’t mean you ought, just because you can deploy meme generating tweet bots to skew elections or opinions in favour of your perspective, even if you believe that perspective is good and true, doesn’t mean you ought. A Philosopher of Technology, Robin K. Hill, has dubbed our propensity to take an ‘ought’ from a ‘can’ as the Artificialistic Fallacy. It’s not necessary that any use of tech is the result of the fallacy; but any assumption that technology will necessarily solve our current situation or make things better, is a fallacy. I wonder if we’re better off, as the church, now because we have technological solutions that weren’t around during the Spanish Flu, our countless other crises and pandemics, than the church living through those times were; or than the New Testament church that got by in various forms of danger or isolation with a few letters from the Apostles (letters themselves being a technology that their own writers acknowledged were limitations — like John saying he’d rather be face to face in two of his letters, and Paul expressing the same idea frequently).

We have a problem with technology and technique as moderns. We accept it, and its extensions of our personhood, almost uncritically — or we don’t engage our critical faculties until it is too late, and the technology has already been incorporated into our ecosystem. Like dinosaurs escaping their enclosures in a dinosaur zoo. Loose, hungry, and destructive.

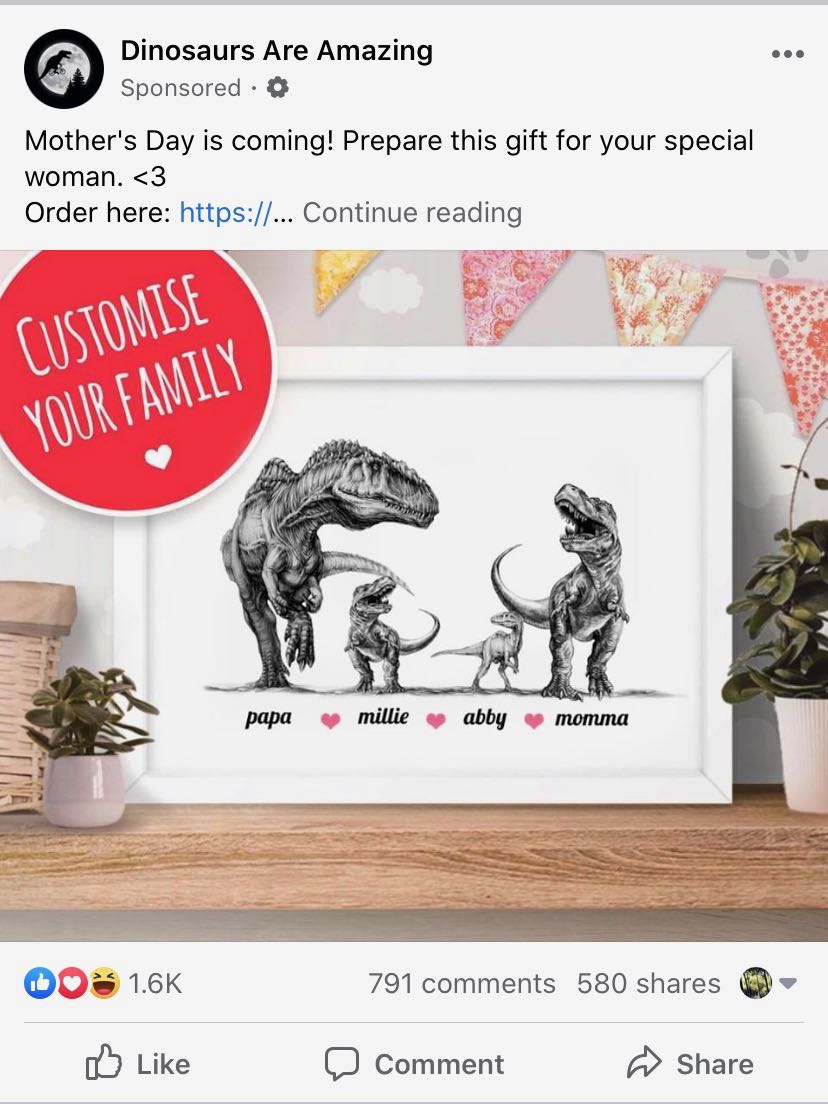

Here’s a fun fact. I wrote some of this post and left it open in a tab in my browser. I have not typed the phrase dinosaurs are awesome anywhere but in this tab. This morning when I opened Facebook I had some new ads in my feed.

I’m not sure a framed picture of our family as dinosaurs is going to cut it for Mother’s Day, but it’s creepy that Facebook’s algorithm either knows me well enough to coincidentally decide that this is something I’m into, or that my as yet unpublished text in a browser has given them more data to mine in order to sell me a solution. This is what has been called ‘surveillance capitalism’ — the sort of economic world we buy into through our uncritical participation in technology; our falling for the fallacy that just because we can (and companies can), we should (and they should).

Much as I love technology, and much as its introduction into our ecosystem is hard to keep safe, and much as uncaging the beast causes massive changes to our safety and day to day lives; I do want to be a dinosaur. Maybe this is part of Tolkien’s “desire for dragons” — maybe I want to live in a world of enchantment, a purer world where technology isn’t linked up with the Babylonian impulse to dominate the natural world, and other people, to secure prosperity for me (or the companies that are part of the fabric of this technology shaped society). Maybe I want to live in a world where it’s easier to sense the presence of God because the way our idolatry has seeped into the construction of our society makes it harder; it’s not that there was an age free from systemic corruption because of sin (see Babel, and then Babylon, and then Rome)… it’s just that it’s hardest to see that in our own age, because idols blind us; and technology plays part of that role in our lives now.

I want to try to reclaim some of what life was like before technology impacted the way we live and relate; and I’m certainly cautious about what sort of devastating impact unleashing the technology dinosaurs into the mix (and the very mixed metaphors) of Covid-19 and family life, and church life, and my own life. Much as I might seek escape into the world of augmented dinosaur battles on Jurassic World Alive, exploring a map littered with digital beasties to capture — I’m in real danger of being conformed in the image of a digital beasty myself.

C.S Lewis, in his inaugural speech at Cambridge, De Descriptione Temporum, suggested that technology — specifically the introduction of the machine — was the major contributing factor in a move from an enchanted to a disenchanted world; the thing that pushed the de-Christianisation of the west faster than any other phenomena. He says our belief in progress — specifically the good of technological advance and our ability to do new things by taking new technology and chucking old stuff, basically forms what Charles Taylor would later describe as our “social imaginary” — the building blocks of our imagination, especially how we understand life in the universe and so how to approach living in the universe. This image of ‘the good’ being ‘technological progress’ means that we often uncritically adopt new technologies and turf old ones. Lewis says this is bigger for our belief in progress, even, than Darwin’s theory of evolution… this is what he calls our ‘new archetypal image’ of how life works.

“It is the image of old machines being superseded by new and better ones. For in the world of machines the new most often really is better and the primitive really is the clumsy. And this image, potent in all our minds, reigns almost without rival in the minds of the uneducated. For to them, after their marriage and the births of their children, the very milestones of life are technical advances. From the old push-bike to the motor-bike and thence to the little car; from gramophone to radio and from radio to television; from the range to the stove; these are the very stages of their pilgrimage.”

C.S Lewis, De Descriptione Temporum

He ended his speech with a note of apology to his students; knowing, even then, that he was speaking to those in post-machine world as a non-native. The man didn’t even use a typewriter because of the impact he thought its machine like rhythms would have on his writing. He said people in a tech-obsessed world should listen to him like they’d listen to a freak — because his critique — from a different world to theirs — might help them look with fresh perspective on their relationship with technology. His approach to medieval literature and the idea that there was an image of the universe in the medieval world closer to the truth than the image we replaced it with when we discarded enchantment (the subject of his academic work The Discarded Image) allowed him, he believed, to see the dangers of the present age differently, even if it meant his students might have to view him as a dinosaur. He was prepared to embrace being a dinosaur.

I claim that, even if the defence of my conviction is weak, the fact of my conviction is a historical datum to which you should give full weight. That way, where I fail as a critic, I may yet be useful as a specimen. I would even dare to go further. Speaking not only for myself but for all other Old Western men whom you may meet, I would say, use your specimens while you can. There are not going to be many more dinosaurs.

— C.S Lewis, De Descriptione Temporum

Interestingly, his intro essay to Athanasius On The Incarnation encouraged people to read old books — not just books from our time — because their concerns would reveal some of the folly of our concerns and practices. There’s a way to become a dinosaur that doesn’t involve virtual reality, but digging in to old books from the past. In Surprised By Joy he talks about the sort of chronological snobbery that helps us jump from the naturalistic fallacy to the artificialistic fallacy via our changed imaginations; we think technology is good and necessary and that we ought do what it allows us simply because we think we’re much more sensible than those who came before us; we’re more highly evolved and have made progress in all areas. Lewis calls this ‘Chronological snobbery.’ Avoiding that might require being a dinosaur, or at least walking with them…

Maybe we need more human dinosaurs before we unleash the technological dinosaurs on our ecosystems anew. Charles Taylor saw ‘excarnation’ working alongside ‘disenchantment’ as the causes of secularity in the modern west. He said this was produced, historically (via the Reformation and its emphasis on the brain/knowledge rather than embodied practice) by “the steady disembodying of spiritual life.” How much faster is that happening via technology? Alan Jacobs, in this fantastic piece Fantasy and the Buffered Self, talks about technology as ‘Janus faced’ — he says our economic and cultural structures are produced by a ‘technocracy’ (the sort of structures present in telco and techno companies and their advertising right now), and this technocracy, through its various institutions, “speaks dark words of disenchantment with one mouth, and the bright promise of re-enchantment with the other.” Technology offers itself as the man made solution, from within a disenchanted frame — a world without God — and we buy it because it lets us be gods, even while it becomes a new god for us; an idol.

Whether we buy the pessimism about the potential danger of letting the T-Rex of Tech loose in in our church ecosystems, or we think we can put the tyrant back in his cage once this pandemic passes, we need to be aware that our jumping in to swim with the tide of technology puts us in a stream that has an ‘end point,’ and connects us with artefacts (technology) that aren’t neutral because they carry their own myth, their own anthropology, and their own eschatology. I’ve been struck, for example, by how much television advertising in night time pandemic viewing has pivoted to telcos and tech companies showing the ‘magic’ of technology; the way technology has transcended space and time to bring us together and keep us creating in this moment.

Amazon Prime is now advertising the show Upload, an alternative Good Place, that looks like it has humanity escaping to the cloud; not the heavenly one with angels, but the digital one. Becoming one with the machine (and hey, Elon Musk reckons we’re already there. That we are digital figments existing in some strange computer game). There’s a whole cultural apparatus pushing us to the idea that the future is digital; the eternal future even. Like the gnostics of old, they see technology freeing us from the meatflesh existence of our bodies (think cyberpunk fiction like Gibson’s Neuromancer). The idea that we might be saved from our bodies and from death and decay by becoming one with the machine is one legitimately explored and advocated by technologists; and celebrated in our advertising (like Telstra’s ‘magic of technology’ ad).

This all follows a trajectory identified by Lewis way back in his first speech in his role at Cambridge, and by Jacques Ellul in the same year, 1954, with his publication of The Technological Society. Ellul was both pessimistic and prophetic about the impacts of technology, and the belief in technique as the path to the good, on our humanity (in the same way McLuhan was later).

“Technique has penetrated the deepest recesses of the human being. The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man’s very essence. The milieu in which he lives is no longer his. He must adapt himself, as though the world were new, to a universe for which he was not created. He was made to go six kilometers an hour, and he goes a thousand. He was made to eat when he was hungry and to sleep when he was sleepy; instead, he obeys a clock. He was made to have contact with living things, and he lives in a world of stone. He was created with a certain essential unity, and he is fragmented by all the forces of the modern world.”

— Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society, 1954

It’s really hard to step back from the impact technology has on us — to unwind its impact on the deepest recesses of our humanity. To undo the ecological impact technology has on us where, in the words of another of McLuhan’s students, “we shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.” The egg can’t be totally unscrambled. And the making of technology is a deeply human task — part of our call to ‘cultivate’ the earth as God’s image bearing people who can imagine and create artefacts; but just because we can doesn’t mean we ought and sometimes we need human, biological, dinosaurs to step back and point out the impact artificial dinosaurs are having on the world we live in; lest we be eaten while on the toilet, or participating in the life of the church.

My hunch is that one of the ways back is less time in man made worlds that rely on technology, and that we interact with using technologies and techniques honed for us by the technocracy, and more time rediscovering the enchanted world we live in; the view those ‘dinosaurs’ from pre-modern times had, and part of that might be walking through the same forests, or looking at the same stars, that they did, or engaging art and stories that throw us into fantasy worlds away from ‘augmented reality’ — the stuff Jacobs advocates in the piece linked above, or Tolkien in On Fairy Stories, the thinking that helped Lewis produce Narnia.

I wish clever technology could do that for me more (and perhaps it can if the tools we create are extensions of our life as creatures created by a creator and we receive them with thanksgiving as gifts from God (1 Timothy 4), the technocracy works to blind us to that ‘enchanted’ dimension of technology; and technology as idol often pulls us away from, rather than towards God… Augmented reality dinosaurs, where my fantasy world, created by clever programmers (who want me to spend money), is mediated to me by a screen, in a way that makes me beastly, don’t do for my imagination or “desire for dragons” what imagining the trees in the bushland up the road from me as living, breathing things that speak to the goodness of my creator does… and yet, that’s what trees are for (Romans 1:20).

“He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods; the reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.” — C.S Lewis