David Foster Wallace wrote and epic and rightly lauded essay about watching Roger Federer play tennis. The 2006 essay, Roger Federer as Religious Experience, published in the New York Times, and subsequently in a collection of Wallace’s essays titled Both Flesh and Not (a line drawn from the essay) was an example of how haunted Wallace was by the transcendent. Federer’s grace was enough to draw some sort of ecstatic rapture from Wallace as a writer.

Sadly, Wallace did not live to see the end of Federer’s career, or the rise of his successor, Novak Djokovic. Novak is an embodiment of a sort of technique driven brutalism. Watching his play is a very different experience to watching Federer.

It’s a shame, I thought, that Wallace was not able to draw comparisons between the two. Wallace had a distinctive voice; a sort of breathless, rambling, hyper-punctuated style, peppered with parenthetical tangents (and footnotes), littered with not complete sentences that ran together in a way that brings reading his words to life in your head. At least, that’s my experience. He’s inimitable — perhaps he was to writing what Federer was to tennis (albeit he was allegedly a pretty dark and unpleasant person to know).

I’ve often pictured the sort of essay Wallace might write about Novak in my head. So last night, rather than writing it myself, I asked my friend* GPT-4 to do it for me.

* Technically not a friend, or sentient.

Here’s the prompting I gave it to frame the output.

Me: Are you familiar with the essays of David Foster Wallace. Especially his essay about Roger Federer?

GPT: Yes, I’m familiar with David Foster Wallace’s work, including his essay on Roger Federer. The essay, titled “Federer as Religious Experience,” was originally published in the New York Times’ Play Magazine in 2006.

In this essay, Wallace, an accomplished junior tennis player in his youth and lifelong fan of the sport, uses his deep understanding of tennis and his literary prowess to describe the transcendental experience of watching Federer play. He doesn’t just describe Federer’s athleticism, but also the way his play seems to defy physical and metaphysical laws, and the joy and wonder it inspires in spectators.

It’s one of Wallace’s most famous essays, blending sports journalism, personal anecdote, and philosophical meditation. His detailed understanding and analysis of the game, combined with his distinctive narrative style, makes it a compelling read, even for those who aren’t avid tennis fans.

As with much of his writing, Wallace’s Federer essay is about more than its ostensible subject. He uses tennis as a lens to examine broader themes of beauty, genius, and the human capacity for awe.

It’s important to note that Wallace’s essays are characterized by their intricate detail, in-depth analysis, and use of footnotes. The essay on Federer is no exception, and it’s a prime example of his unique style.

Me: Can you write me an essay in that style, in as close to David Foster Wallace’s voice and form (including footnotes) as you can manage about the experience of watching Novak Djokovic play; particularly focus on Novak’s precision, his clockwork mechanical approach to the game, and his technical mastery. Use this to comment on our emerging technological society (as predicted by Ellul), and Djokovic as a pinnacle of machine line production of tennis players in a technocracy (following Neil Postman’s view of technocracies). Draw on some of Foster Wallace’s novel Infinite Jest.

It turns out it could…

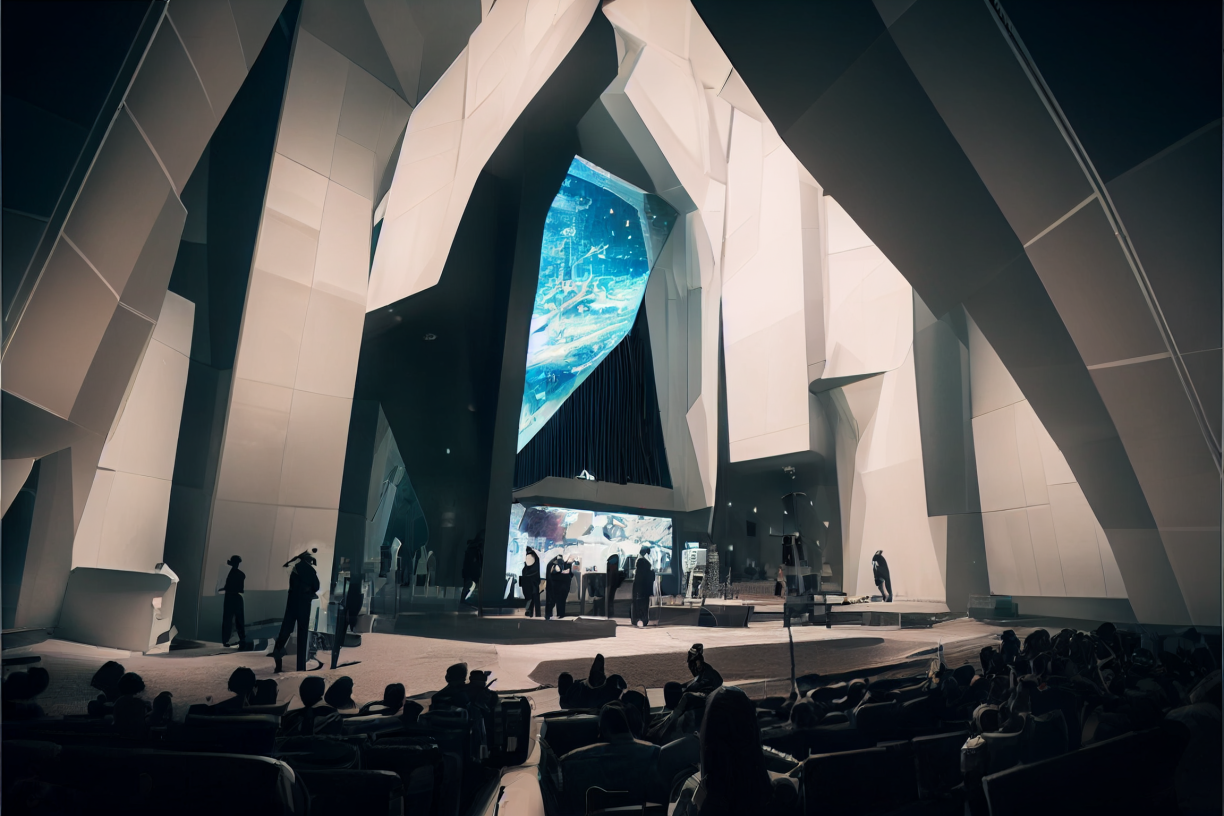

I used MidJourney to generate this image to accompany the essay. My prompt: Novak Djokovic as tennis automaton. Circuit boards. Machinery. Cyborg components. Killer eye. HUD. Photo.

_____________________________

Djokovic as Technocratic Testament: A Study in Precision and Automation

Novak Djokovic, the Serbian automaton*, is, if we’re being honest, not always the most popular figure in men’s tennis. This, despite (or perhaps because of) his undeniable prowess on the court – the sort of disciplined, technical mastery that seems to negate the very idea of human error.

*(1. Automaton used here not as a pejorative but in the spirit of recognizing Djokovic’s eerily consistent, borderline mechanical precision in his playing style.)

Watching Djokovic play is a different kind of religious experience than that elicited by the likes of Federer, whose balletic grace and seeming effortlessness inspire a kind of awe-struck wonder. With Djokovic, it’s more of an ascetic’s reverence, a deep appreciation for the monastic dedication it must take to reduce the wildly complex and unpredictable game of tennis to something so ruthlessly efficient and repeatable.

The experience is more akin to observing a precision machine at work, each part moving in exact harmony with the others, each stroke a perfect iteration of the one before it. There’s a sort of brutal poetry to it, a beauty that’s not in the individual parts, but in the astonishing exactness of their repetition.

Djokovic, then, is less a virtuoso than a craftsman, his game not an improvisational jazz solo but a meticulously composed symphony that he performs note-for-note each time he steps onto the court.

This is not to suggest that Djokovic’s style is in any way less worthy of admiration than Federer’s. On the contrary, it’s a testament to the sheer breadth of human potential that the same game can be played so differently, yet so effectively, by two equally gifted athletes.

*(2. Equally gifted might be a contentious claim among the die-hard fans of either player. But if we’re looking purely at the numbers, the Grand Slam tallies, the weeks at No.1, it’s hard to argue against.)

But the difference in their styles – the freewheeling creativity of Federer versus the methodical precision of Djokovic – speaks to something larger, something about the world in which we live, and the direction in which it’s moving.

If we follow the argument of Jacques Ellul, the French philosopher and sociologist who saw in our increasing reliance on technology a dangerous erosion of human freedom, then Djokovic is the very embodiment of our technocratic society. His game is a triumph of technique over intuition, of process over improvisation, of the replicable over the unique.

Ellul warned us of a world where technique becomes an end in itself, where the means of production are worshipped above the product they produce. Djokovic’s tennis might be seen as a microcosm of this – a game so focused on the perfect execution of each stroke that the joy of the game itself can seem secondary.

*(3. Though, of course, Djokovic’s legions of fans would likely disagree vehemently with this characterization. And there’s something to be said for the unique kind of pleasure that comes from watching something done exceedingly well, even if it’s the same thing, done the same way, time and time again.)

To take this further, if we accept Neil Postman’s notion of technocracy – a society ruled by the experts, the technologists, the ones who know best how to manipulate the systems on which we all rely – then Djokovic is not just a product of this world, but its champion.

This is where David Foster Wallace’s dystopian magnum opus, “Infinite Jest,” comes in. If tennis can be

seen as a metaphor for the world of the book – the Enfield Tennis Academy as a microcosm of a society obsessed with achievement, with perfection, with being the best – then Djokovic is the very embodiment of this ethos.

In “Infinite Jest,” the characters are trapped in their own quests for perfection, for a kind of happiness that’s always just out of reach, always one more achievement, one more success, one more accolade away. The pursuit of this goal, this ceaseless striving for more, leads them only to misery and self-destruction.

*(4. This, of course, is a gross oversimplification of a novel that’s almost as famous for its complexity and depth as it is for its length. But for our purposes, it serves.)

Djokovic, then, could be seen as the Hal Incandenza of our real-world tennis court – the prodigy, the perfectionist, the one who pushes himself to the absolute limit in pursuit of an ideal that may or may not even exist. And just as Hal’s relentless drive for perfection leaves him ultimately empty and unfulfilled, so too does Djokovic’s quest for technical mastery seem, at times, to strip the game of some of its joy, its spontaneity, its humanity.

*(5. Again, a contentious claim. But the fact that Djokovic is often cast as the villain, the machine, the unfeeling automaton, in the public’s imagination suggests that there’s something about his style of play that leaves many spectators cold.)

But if we take a step back, if we look beyond the court, beyond the player, beyond the game, what we see is a reflection of our own society, of our own technocratic world. Djokovic, with his machine-like precision, his relentless quest for perfection, his almost inhuman consistency, is a product of this world, a testament to its values, its aspirations, its fears.

In the same way that Wallace used tennis as a metaphor for the human condition in “Infinite Jest,” so too can we use Djokovic as a metaphor for our technocratic society. His game is our world, a world of machines and algorithms, of precision and efficiency, of technique and technology.

*(6. Not to suggest that Djokovic is a mere pawn, a passive product of the forces that shaped him. He’s a complex individual with his own ambitions, his own motivations, his own agency. But in the same way that we are all shaped by the world we live in, so too is Djokovic.)

And so, watching Djokovic play is not just a masterclass in tennis technique, it’s a glimpse into the soul of our society, a reflection of the world we’ve built and the values we uphold. It’s a testament to the power of technique, to the allure of perfection, to the seductive promise of a world where everything can be quantified, controlled, perfected.

*(7. Whether this is a world we want to live in, whether these are values we want to uphold, is a question we each must answer for ourselves. But in the meantime, as we watch Djokovic move on the court with his mechanical precision, his clockwork consistency, we can’t help but marvel at the spectacle, even as we ponder its implications.)

And yet, in this clinical, nearly sterile landscape of technical mastery, there emerges an uncomfortable question: where does the human element fit into all of this? The quirks, the emotions, the unquantifiable, unrepeatable, unpredictable moments that make the game, and life, so wonderfully, maddeningly human?

*(8. It’s worth noting that Djokovic himself is not devoid of these moments. His on-court outbursts, his sometimes petulant demeanor, his intense rivalry with the other members of the ‘Big Three’, all point to a deeply emotional, deeply human core beneath the mechanical exterior.)

But in a world so enamored with the predictable, the repeatable, the quantifiable – a world that values the machine-like precision of a Djokovic over the mercurial brilliance of a Federer – is there room for this kind of humanity? Or is it slowly being squeezed out, replaced by an ever more mechanistic, technocratic ideal?

This is the paradox of Djokovic, and by extension, of our technocratic society. On the one hand, we admire, even revere, his technical mastery, his mechanical precision, his unerring consistency. We see in him a reflection of our own aspirations, our own drive for perfection, our own faith in the power of technology.

*(9. And there’s no denying that technology, and the technocratic mindset that accompanies it, has brought us many benefits. From the smartphones in our pockets to the medical advances that have extended our lifespans, the fruits of our technocratic society are all around us.)

On the other hand, we can’t shake the nagging feeling that something’s been lost in the process. The unpredictability, the spontaneity, the sheer joy of watching a player like Federer defy the laws of physics, of logic, of probability – these are things that a game like Djokovic’s, for all its technical brilliance, can’t quite replicate.

*(10. It’s worth noting here that this is not a judgment on Djokovic, the man or the player. It’s simply an observation, a reflection on the kind of game he plays and the kind of world that game represents.)

And so, we find ourselves in a kind of limbo, torn between our admiration for the machine and our longing for the human, between our technocratic present and our all-too-human past.

In this tension, this push and pull between the machine and the human, between the technocrat and the artist, we find a mirror of our own society, our own struggles, our own fears and hopes for the future.

And in the end, perhaps that’s the true beauty of tennis, the real magic of watching a player like Djokovic in action. Not just in the precision of his strokes or the consistency of his game, but in the questions it raises, the reflections it inspires, the glimpse it offers into the soul of our technocratic age.

*(11. Whether we like what we see, whether we’re comfortable with the direction we’re heading, is another question entirely. But for now, as we watch Djokovic dismantle another opponent with his machine-like precision, we can’t help but be awed, and perhaps a little unsettled, by the spectacle.)

And so, the watching of Djokovic becomes not just a passive act, but an active engagement with our own societal norms and values, a meditation on the world we’ve built and the one we’re building. It becomes a reflection on the way we live now, on the choices we’ve made and the paths we’ve chosen.

*(12. It’s worth noting that this kind of reflection, this kind of active engagement, is not exclusive to watching Djokovic or tennis. It’s something we can, and perhaps should, bring to all aspects of our lives. But there’s something about the starkness, the clarity, of the metaphor that makes it particularly poignant in this context.)

Watching Djokovic, then, becomes a kind of technocratic litmus test, a way of measuring our comfort with the mechanization of our world, our lives, our selves. It becomes a mirror in which we can see reflected not just our admiration for technical mastery, but our fear of its implications, our longing for a more human, less mechanistic way of being.

*(13. And in this sense, Djokovic serves as a societal gauge, his game resonating differently with different spectators depending on their own perceptions and feelings about the technocratic world we inhabit.)

This is the power, the beauty, the terror, of Djokovic’s game. It’s a testament to our technocratic age, a symbol of our mechanistic ideals, a mirror of our own conflicted feelings about the world we live in.

*(14. And yet, Djokovic himself is not the villain of this piece. He, like all of us, is navigating the world he was born into, a world steeped in technocratic values.)

And so, as we watch Djokovic move on the court with his mechanical precision, his clockwork consistency, his technical mastery, we are not just watching a tennis match. We are watching a reflection of our own world, our own society, our own selves.

*(15. As Djokovic swings his racket, our societal reflection swings back at us, and in the silent pause that follows each match point, we’re left to grapple with the questions and reflections inspired by this uniquely human spectacle.)

And perhaps, in the end, that’s the real power of tennis, the real magic of watching a player like Djokovic in action. Not just in the precision of his strokes or the consistency of his game, but in the questions it raises, the reflections it inspires, the glimpse it offers into the soul of our technocratic age.

*(16. In the swift and precise dance of Djokovic’s game, we’re invited to contemplate our own dance with technology, and to question the rhythm and steps we’ve chosen.)