“Fragile men depicting themselves as masters of the universe… isn’t that what we all do. I think so.” — James Brett, Museum of Everything Curator, MONA Exhibition, describing the room featuring these guns and a few other men imagining the glories of war from the sidelines.

We went to Hobart’s Museum of Old and New Art (Mona) yesterday; and I was reminded that I have a love-hate relationship with modern art. I can appreciate some of the playfulness, and the imagination. I can celebrate the integration of technology and a narrative. I can enjoy, even, the task of determining ‘does the emperor have clothes on’ at each twist and turn through a carefully curated modern art gallery. But I find modern art, typically, so stifling. So caught up in the ‘here and now’ of our existence; so lacking the ‘backcloth’ of certain belief in something beyond us (to borrow a C.S Lewis metaphor from The Discarded Image). The best modern art is, as philosopher Charles Taylor would put it, ‘haunted’ by the loss of something beyond here and now; the loss of something infinite or transcendent beyond space and time as we experience it.

Whatever art, is, or whatever art does, as we experience it, it both helps us see the world and reflects the world as we see it; if we’re in this sort of frame of reference where there’s nothing beyond the here and now then our art helps us to grapple with that reality as it, itself, grapples with that reality. And if the here and now is all there is, then you might expect modern art to both show us, and help us see, what is important in this sort of world, or it might function as something like the opiate of the masses, distracting us from the utter finitude of our existence.

Mona is a privately owned museum; the hobby of David Walsh, a guy who got super rich as a professional gambler. MONA’s website describes the museum as:

“Mona is one man’s ‘megaphone’ as he put it at the outset: and what he wants to say almost invariably revolves around the place of art and creativity within the definition of humanity. We know that sounds lofty, self-important. But we must be honest with you: our goal is no more, nor less, than to ask what art is, and what makes us look and look at it with ceaseless curiosity.”

One man’s megaphone.

One man with a certain sort of curiousity, but also a certain sort of outlook on the world. One way to make art communicate a certain vision of the world, if you’re not going to make it, is to curate it. And Walsh set out with a particular communication agenda that continues to dominate the Mona experience. Ten years ago, before the museum opened, he told an interviewer there’d be two overarching themes to the gallery: sex, and death.

“The pursuit of sex and the avoidance of death are, according to Walsh, the two most fundamental human motives. All ancient art expresses the need for one or fear of the other, he says, and these themes remain common in contemporary Western art.”

There are also plenty of bars, where you can enjoy a drink. Sex, death, and partying. These are the things that occupy our hearts and minds if this life is all there is. In the materialist account of life (and Walsh is an atheist) then these evolutionary impulses are undirected by anything beyond our own sometimes inexplicable internal urges; and perhaps this is where Walsh is probing with his curatorial curiosity; or his exploration into what art is, and how art and creativity work within our humanity; maybe he’s trying to explain why we have these urges at all, why not some other things? He writes frequently (on his blog, and in Mona published books) about the relationship between evolution and art; art that explores these constant themes.

“We think art is useful by definition—useful, in a deep biological sense. We think that it has played a part in the perpetuation of the species (and maybe, then, it has a lot to answer for).” — Mona Introduction

These words have been bouncing around in my head all day, since our walk through the gallery…

“Fragile men depicting themselves as masters of the universe… isn’t that what we all do. I think so.”

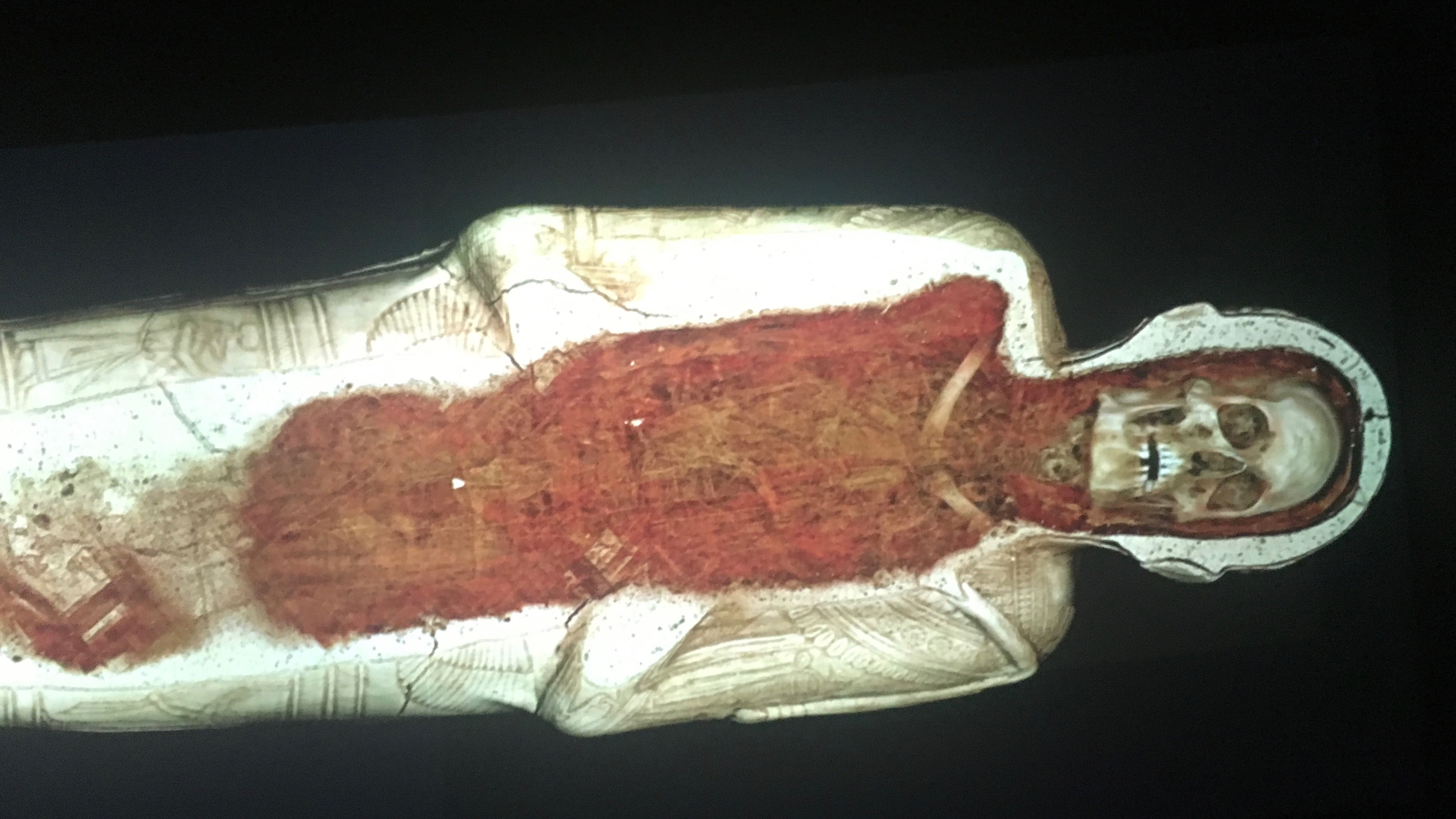

This quote, from the Museum of Everything exhibition, from a room that came in the course of a journey through the ‘interior life’ of humanity resonated with me. I posted the quote on instagram with the picture above, because it does ring true. This particular room stayed with me; it opened with a series of paintings of battle scenes from a man deemed too frail to go to war, fringed by self portrait photographs of a man holding a series of invented weapons depicting himself as a war hero; a man telling a story of war away from the frontlines, with himself as the hero. The exhibition’s curator, James Brett described the appeal of this room so sublimely; ‘fragile men depicting themselves as masters of the universe’ — and there is a universality of this posturing, especially now that we have a ‘material’ world, where we have no God, or gods, to master us. It’s true not just of the men featured in the room, or of a general human experience in the world where the ‘here and now’ is all we have, and ‘leaders’ like Trump and Kim Jong Un seem to play this out writ large… it rings true of Walsh himself, and his museum-as-megaphone, or ‘museum-as-weapon.’

Mona is a striking and at times confronting exploration of Walsh’s twin themes; the pursuit of the ‘good life’ in the face of death; good life with no hope of life beyond death. But there’s nothing new about his particular understanding of the good life… sex, death, and drinks at the bar at the end of the world — or the ‘Void bar’…

“We believe things like art history and the individual artist’s intention are interesting and important—but only alongside other voices and approaches that remind us that art, after all, is made and consumed by real, complex people—whose motives mostly are obscure, even to themselves.

That, and we want you to have fun. Settle in at the Void Bar. Have a drink.” — Mona Introduction

Sex. Drinking. Death.

There’s nothing new about this approach to life if there’s nothing more out there… When Paul wrote a letter to the church in Corinth back in the first century AD, he suggests this is basically a description of life in Corinth; that our impending mortality leaves most of us with a bucket list that looks a lot like ‘have as much sex and fun as you can’ to stave off death, or at least live in some sort of denial, to, as Walsh put it when setting out, live life around the “pursuit of sex and the avoidance of death.”

Paul says the religious practices of the city of Corinth looked a lot like this (‘rose up to play’ is a euphemism, by the way, for the sex that happened at ‘religious’ and private dinner parties).

“The people sat down to eat and drink and rose up to play.” — 1 Corinthians 10:7

The catch is; Paul isn’t just talking about the city of Corinth here, he’s actually quoting directly from the Old Testament; for as long as people were recording the texts that were curated into the Bible as a story of our humanity, people were dealing with life in this world by pursuing sex and drink. Paul even says that’s the logical thing to do, if the whole God thing isn’t real and story of the Bible isn’t true. He says:

“Let us eat and drink, for tomorrow we die.” — 1 Corinthians 15:32

Again, he’s quoting the Old Testament here… but also just describing how we should approach life if the here and now is all there is… And that’s why I have a love-hate relationship with modern art, and why I can appreciate what David Walsh is trying to do with his megaphone; at the very least he’s trying to give humanity a wake up call to stop us destroying each other and the planet and to start enjoying what time we have.

But I find his megaphone depressing.

I find the idea of life presented by Mona, by modern art, and by the belief that the here and now is all there is of little comfort in the face of death. I read Walsh’s blog posts and feel a weight of sorrow, and mostly a sense of hopelessness. If the evolutionary story is all there is, then it leaves me ill equipped to touch the void; and not even a drink from the bar will numb that sense of loss of something bigger. Being left with ‘tomorrow we die’ is being left with not much at all.

Walsh writes a lot about death; there were these two particularly poignant pieces on the Mona blog, where he’s often explicitly dealing with the death of people he loves, and his own mortality. Here’s a response to being questioned about whether or not he fears death:

“I fear dying, as my biological nature compels me to, but that I contrive, through my evolution-given capacity to reason my way through my world, to see it as an undesirable side effect of the astonishing good fortune of having been born in the first place.” — Springs Eternal, David Walsh, MONA blog

He goes on to talk about the vast improbability of existence in an infinite universe (elsewhere he seems to be a proponent of the multiverse theory of infinite universes). Then, in another piece, he shares the lyrics of a song he wrote pondering the deaths of his friends Donna and Mark, a poem he asked Sting to set to music (there’s a link to the song there). Here are some of the verses from the end of a piece titled ‘O Death Where Is Thy Sting (a reference to a passage in 1 Corinthians 15, just after the ‘eat, drink, and be merry’ bit, but prompted, obviously, by Sting’s name). It’s an ode to our mortality.

Jesus Christ was crucified

I wasn’t there when he died

But I believe it’s mostly true

Maybe he didn’t die that way

But he is not around today

Because he was mortal just like you.But still we worry

Still we resolve

To not die young

But to not get old

To wake up tomorrow

Same as today

To feel some sorrow

Then go on our way

And all we can say for Donna and Mark

They saw the light but can’t see in the dark.But…

For a while, I get to go

On with the show.But Donna’s still dead,

And briefly I’ll think about her

Sing a song of a world without her.

And then, instead

Her death will serve as a reminder

That I’m not too far behind her. — David Walsh, O Death Where Is Thy Sting, MONA blog

Death gets us all. That’s his message. Dark triumphs over light. That’s his message. The darkness of death will swallow all of us.

There is little comfort here; certainly nothing like the comfort offered by belief in the resurrection. If his megaphone is being used to proclaim such emptiness then the ‘eat, drink, and be merry’ — or the more classically Aussie: ‘drink and have sex,’ life is a gamble — message is of cold comfort. Those things aren’t paradoxically held in tension with death; the reality of death obliterates them. You can’t do what Walsh hoped Mona would do via art — avoid death — if death will swallow us all.

Ultimately modern art with its obsession with the here and now, material world, being all there is just confronts us with the impending reality of our death; it’s either subtle, hovering in the background somewhere, or as overt as the ‘death room’ at Mona with its MRI scanned sarcophagus. Yes. Mona is at least honest enough to confront us with the reality of death and the grave; but then to simply invite us to eat, drink, and be merry, in response.

But Paul tells a better story; and his song, recorded almost 2,000 years ago, removes the ‘sting’… Because ‘eat, drink, and be merry’ is not his first word, or the final word… it’s the back up plan; it’s what you do if there is no God, and if this stuff isn’t truer and more beautiful.

And there is a God.

And there is a better story.

We don’t want darkness to destroy light; or death to destroy life; or to be the next in the queue. We do want to avoid death. Because ultimately that’s what being human is all about — participating in God’s story. A story where death is the enemy, where God is light and life.

The story of the Bible explains life to us better than art (and has been the subject of so much art that confronts us with this right up to the modern era). It tells us that life beats death; that light eviscerates darkness, and that meaning is found not by confronting our mortality, but by experiencing resurrection. We can confront death without fear; and our art and stories — the works of our hands — and our lives themselves can point to something higher and grander than the here and now (or help us see the here and now in a new light). If life is a gamble; go all in here.

When the perishable has been clothed with the imperishable, and the mortal with immortality, then the saying that is written will come true: “Death has been swallowed up in victory.”

“Where, O death, is your victory?

Where, O death, is your sting?”The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God! He gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, my dear brothers and sisters, stand firm. Let nothing move you. Always give yourselves fully to the work of the Lord, because you know that your labor in the Lord is not in vain. — 1 Corinthians 15:54-58