Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules For Life: An Antidote For Chaos is going gangbusters in Australia; and he’s speaking to a sold-out auditorium here in Brisbane tomorrow evening, so I’ve been ploughing through his work (including the book) and trying to figure out what makes him resonate so strongly with Aussie blokes (perhaps especially with Christians). This is the first of (at least two) posts interacting with Peterson’s book.

One thing I’ve appreciated about Peterson is that because he’s into Jungian psychology he stresses the importance of story, and particularly because he’s a champion of the west (and western individualism) the particular formative importance of the Christian story; or at least his version of the Christian story as the ultimate human archetypal narrative that teaches us most of what we need to know to live a good (western individualistic) life. He’s been particularly popular among western blokes and his no-nonsense appeal to take responsibility stands in a certain sort of tradition of addressing wisdom to blokes — one we find in the Bible; only, there are some problems with the scope of his ‘wisdom’ (and where it begins) that mean there’s a strong possibility his advice will end up being bad for anybody other than the ‘strong’ — who end up being those the western world privileges — which, already, by most measures of ‘success’ or ‘goodness’ are people just like him (and me), the very people lapping up his vision for the good life, the ‘winners’ in the western world. White blokes. Particularly educated and able white blokes. I’ll dig into this in the subsequent post on his treatment of order and chaos as masculine and feminine, but it’s worth reading this review from Megan Powell Du Toit to hear how he is heard by wise women.

There’s something to him and his serious engagement with the story of the Bible that makes you wonder if maybe we’re witnessing a long and public conversion; perhaps if YouTube had been around while C.S Lewis was writing and publishing in the lead-up to his conversion it might have felt the same. What is particularly interesting is what Peterson does with Christianity — with the story of the Bible.

Peterson and the mythic redemption of masculinity

Part of Peterson’s appeal is that he offers some pushback to a (secular) movement in the west that is aiming to level the playing field for non-white-men, that some blokes feel dehumanised or demonised by; part of his pushback is the idea that the good things about the west are a product of its Christian heritage, that not all white men are terrible, and in many ways the way the story of Christianity changed the way the white blokes from the pre-western world slowly started to include others in their thinking about how the world should be won (we’ve got to remember that Julius Caesar was an ‘archetypal’ white bloke, and the world would look very different now if it was shaped more profoundly by Caesar than by Jesus (who was a bloke, but not white)).

There’s nothing inherently wrong with being a bloke; with being white; or with being born into privilege historically, globally, and economically. The question is what to do with privilege or power… and here’s where Peterson dallies with some dangerous ideas, and where his incomplete picture of the Bible might cause us to come unstuck.

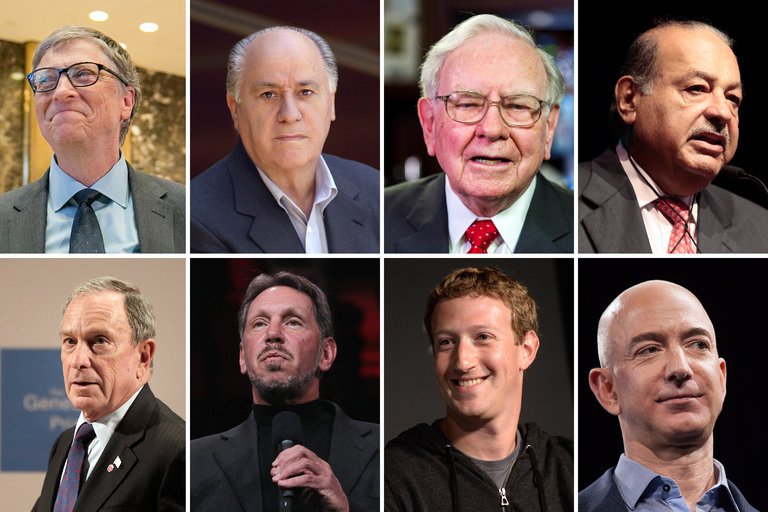

It’s also worth remembering that while there’s a bunch of white blokes — perhaps especially in America, and perhaps those whose imaginations were most captured by the Trump campaign — who feel like victims in a bold new world. These blokes also often sense that the main people causing their victimhood — the oppressors — are the ‘left’, those seeking systemic change to elevate women, people of colour, and other minorities to the positions in society often held by white blokes in a way that sometimes feels demonising in the rhetoric around the role white blokes have played in shaping this world; and sometimes, frankly, is demonising… And, amidst this remembering, it’s perhaps worth reminding these white blokes (and all of us) that it’s not really the left taking away jobs and keeping the white man feeling down, and angry, it’s the powerful and the wealthy who sit atop what Peterson would call a dominance hierarchy. You want to talk about job losses for the working class? Talk about the people behind the tech companies that are innovating and automatic manual labour; talk about the people taking the lion’s share of company profits through bonuses and off the back of the work of others… talk about these eight blokes whose combined wealth is greater than the combined wealth of 50% of the planet. That’s obscene; and how can it not be oppressive?

To the extent that Peterson does offer a solution for men emasculated by a culture of dominance — by dominance hierarchies that we, as individuals rather than a class, are not on top of — is to invite the individual to redefine the parameters they measure success by; and to take responsibility for their own lives — to commit to making the world more like heaven than hell — which isn’t, in itself, terrible advice.

His antidote to the chaotic dissolution of community life is for individuals to take responsibility for themselves; which seems counter-intuitive, but is advice I’ve found a particular balancing corrective to my growing frustration with our whole-scale adoption of western individualism in the church, as Chesterton wrote in Orthodoxy, Christianity is a collection of furious opposites; a robust Christianity “got over the difficulty of combining furious opposites, by keeping them both, and keeping them both furious”; paradox is at the heart of wise negotiation of the world we live in, and it is certainly true that we are both individually responsible creatures, and social creatures who are embedded in identity-defining communities built on shared stories (be it the family, the tribe, the nation, the workplace, the church, etc). Peterson is big on the power of stories, but he emphasises the idea that to be fully realised as a person, one must embrace the ‘heroic path’. There’s a strong hint of Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey under the hood here — Campbell was an expert on ‘myths’ and the way we organise our lives, and sense of the good life, through stories rather than facts; and especially through archetypal heroes, or ‘super men’.

“How could the world be freed from the terrible dilemma of conflict, on the one hand, and psychological and social dissolution, on the other? The answer was this: through the elevation and development of the individual, and through the willingness of everyone to shoulder the burden of Being and to take the heroic path. We must each adopt as much responsibility as possible for individual life, society and the world.” — Page XXXIII (prologue)

This message — and some of Peterson’s schtick — has resonated particularly with men. And you can see why a bit; but it is a message of only limited use. The “burden of being” is the fundamental reality of suffering; it was this reality, Peterson said, that caused him to leave the faith of his childhood (though it seems he has returned to the mythic stories of his childhood to continue making sense of the world).

But I was truly plagued with doubt. I had outgrown the shallow Christianity of my youth by the time I could understand the fundamentals of Darwinian theory. After that, I could not distinguish the basic elements of Christian belief from wishful thinking. The socialism that soon afterward became so attractive to me as an alternative proved equally insubstantial; with time, I came to understand, through the great George Orwell, that much of such thinking found its motivation in hatred of the rich and successful, instead of true regard for the poor. Besides, the socialists were more intrinsically capitalist than the capitalists. They believed just as strongly in money. They just thought that if different people had the money, the problems plaguing humanity would vanish. This is simply untrue. There are many problems that money does not solve, and others that it makes worse. Rich people still divorce each other, and alienate themselves from their children, and suffer from existential angst, and develop cancer and dementia, and die alone and unloved. Recovering addicts cursed with money blow it all in a frenzy of snorting and drunkenness. And boredom weighs heavily on people who have nothing to do. — Page 196

Peterson is a moral philosopher for the secular age, in Charles Taylor’s use of the term; though haunted by the possibility that there might be something to all the Christian stuff he find so compelling, he starts with the assumption that it is a human response (as sophisticated as it might be) presenting human truth (because he would say the Bible is definitely a true account of our humanity) to human problems. There is no external agency promoting evil; evil dwells in all of us — the serpent in Genesis is a manifestation of the human psyche, it represents the hostility of the world we live in (serpents being the ancient archetypal enemies of evolving humanity) but the real serpent for us to conquer is within us; the real hell is a hell where we inflict that evil on others, and heaven is a world where people imitate the archetypal life of Jesus. In short; Peterson wants Christianity to be true, but for him it’s truth without transcendence about a self caught up in internal (and eternally) conflict with itself. His work on the burden of being is an extended treatment of the idea expressed in Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous quote: “If only it were all so simple! If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

This is chaos. This is what must be mastered. This is the issue he tackles. While he might doubt God, he is sure of one thing… the reality of suffering and the particular capacity for evil lurking in every human heart and emerging at various points in history, and the lives of individuals.

What can I not doubt? The reality of suffering. It brooks no arguments. Nihilists cannot undermine it with skepticism. Totalitarians cannot banish it. Cynics cannot escape from its reality. Suffering is real, and the artful infliction of suffering on another, for its own sake, is wrong. That became the cornerstone of my belief. Searching through the lowest reaches of human thought and action, understanding my own capacity to act like a Nazi prison guard or a gulag archipelago trustee or a torturer of children in a dungeon, I grasped what it meant to “take the sins of the world onto oneself.” Each human being has an immense capacity for evil. — Page 197

Peterson’s view of the human condition is — in Taylor’s diagnosis — ‘buffered’ — there is no cosmic problem external to ourselves; so we can save ourselves. Evil is not ‘out there’ but in here. The problem with the world is, as Chesterton put it, the individual. It’s you. It’s me. Or, as he says when unpacking the Bible’s account of evil as an archetypal story, from Genesis 3… there’s no external, supernatural force, no Satan; the serpent is, for him, a projection from within the self (echoed by many selves).

And even if we had defeated all the snakes that beset us from without, reptilian and human alike, we would still not have been safe. Nor are we now. We have seen the enemy, after all, and he is us. The snake inhabits each of our souls. This is the reason, as far as I can tell, for the strange Christian insistence, made most explicit by John Milton, that the snake in the Garden of Eden was also Satan, the Spirit of Evil itself. The importance of this symbolic identification—its staggering brilliance—can hardly be overstated. It is through such millennia-long exercise of the imagination that the idea of abstracted moral concepts themselves, with all they entail, developed. Work beyond comprehension was invested into the idea of Good and Evil, and its surrounding, dream-like metaphor. The worst of all possible snakes is the eternal human proclivity for evil. The worst of all possible snakes is psychological, spiritual, personal, internal…— Page 46

A quibbling detail — that the serpent is Satan was made pretty explicit in John’s apocalypse, the book of the Bible we call Revelation; and one that suggests that actually, behind all human evil there is a puppeteer — a serpent; tempting and pulling us towards evil. John invites us to see reality as something more like a cosmic, supernatural, battle ground than our secular age ‘buffered selves’ can envisage… You can’t simply hold on to the words of the Bible as secular myth. It evades such neat categorisation. Yes, there is darkness in every human heart, but to view the human heart as ‘buffered’ — to see us simply as individuals locked in a battle with the self, rather than as people picking sides in a cosmic battle between good and evil misses the mythic heart of the Bible’s claims about the world and us. The mythos of the Bible; it’s organising principle, is that Jesus came to triumph over the darkness of sin, death, and Satan.

But if the problem is just us, if the world is closed to the supernatural, and the natural is all there is, these stories might work the way Peterson suggests, and, in a limited sense, we can start fixing and redeeming the world bit by bit, life by life, as we set our gaze just a little bit higher. His 12 Rules are aimed at addressing this problem. They’re derived from a particular moral outlook, a particular picture of how the individual might bring order out of the chaos in the individual heart; there’s a reason his book is categorised as ‘self-help’, because it is that in the most fundamental and literal sense of the genre. His solution is help yourself.

The problem is, if we individualise and internalise the problem of the burden of being, and if the Bible is the sort of source of truth Peterson insists, and if we individualise the solution to that problem, then we doom ourselves. We can’t help ourselves escape from ourselves. Even if we know what good looks like; our hearts are shot through with evil. The Biblical account of human behaviour Peterson loves so much goes a bit further than Solzhenitsyn in its diagnosis of the heart:

The Lord saw how great the wickedness of the human race had become on the earth, and that every inclination of the thoughts of the human heart was only evil all the time. — Genesis 6:5

For Peterson the cross is an archetype of the sort of life that might produce this change… it’s strangely, for him, the ultimate natural heroic story. It gives us a pattern for making atonement for ourselves and the evil within; for a wise life; for fighting back against chaos and darkness. Peterson calls people to take up their cross to make atonement for your own contribution to the problems of the world. He wants Jesus to be our archetype for the good human life; not our saviour or the one who makes atonement for us. He offers a certain sort of salvation by works… but a salvation not so much looking to an afterlife; but designed to bring ‘heaven on earth’.

To stand up straight with your shoulders back is to accept the terrible responsibility of life, with eyes wide open. It means deciding to voluntarily transform the chaos of potential into the realities of habitable order. It means adopting the burden of self-conscious vulnerability, and accepting the end of the unconscious paradise of childhood, where finitude and mortality are only dimly comprehended. It means willingly undertaking the sacrifices necessary to generate a productive and meaningful reality (it means acting to please God, in the ancient language). To stand up straight with your shoulders back means building the ark that protects the world from the flood, guiding your people through the desert after they have escaped tyranny, making your way away from comfortable home and country, and speaking the prophetic word to those who ignore the widows and children. It means shouldering the cross that marks the X, the place where you and Being intersect so terribly. It means casting dead, rigid and too tyrannical order back into the chaos in which it was generated; it means withstanding the ensuing uncertainty, and establishing, in consequence, a better, more meaningful and more productive order. — Page 27

Once having understood Hell, researched it, so to speak—particularly your own individual Hell—you could decide against going there or creating that. You could aim elsewhere. You could, in fact, devote your life to this. That would give you a Meaning, with a capital M… That would atone for your sinful nature, and replace your shame and self-consciousness with the natural pride and forthright confidence of someone who has learned once again to walk with God in the Garden. — Page 64

It was from this that I drew my fundamental moral conclusions. Aim up. Pay attention. Fix what you can fix. Don’t be arrogant in your knowledge. Strive for humility, because totalitarian pride manifests itself in intolerance, oppression, torture and death. Become aware of your own insufficiency—your cowardice, malevolence, resentment and hatred. Consider the murderousness of your own spirit before you dare accuse others, and before you attempt to repair the fabric of the world. Maybe it’s not the world that’s at fault. Maybe it’s you. You’ve failed to make the mark. You’ve missed the target. You’ve fallen short of the glory of God. You’ve sinned. And all of that is your contribution to the insufficiency and evil of the world…

Consider then that the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering is a good. Make that an axiom: to the best of my ability I will act in a manner that leads to the alleviation of unnecessary pain and suffering. You have now placed at the pinnacle of your moral hierarchy a set of presuppositions and actions aimed at the betterment of Being. Why? Because we know the alternative. The alternative was the twentieth century. The alternative was so close to Hell that the difference is not worth discussing. And the opposite of Hell is Heaven. — Page 198

This is Peterson’s picture of how to be a man. A human. But is it possible? Does it change anything substantial about the world we live in where very strong men rule by dominating and perpetrating evil? What change would it bring to any of those eight men and how they use or view their wealth and their work (which they’d all describe as bringing a certain sort of order)? Does it actually work to deal with the darkness in our hearts this way?

Can Peterson’s mythic Jesus save us from ourselves?

Peterson champions individual responsibility in the face of suffering, and something very much like Nietsche’s will to power and he really, really, tries to understand the cross of Jesus and its place in the ‘archetypal story’ of the ‘archetypal’ hero of the west; the one man, or character, who truly carried the burden of the being. I want to be as positive and charitable to him though, because I think he’s genuinely searching for a way of life in this world that makes the best sense; of the data, and of how we’re wired (and the stories — myths — we tell generation after generation to encode a certain sort of participation in the world). He quotes Romans ‘you’ve fallen short of the glory of God’, but misses the mark on the solution Romans offers for this… The problem is, without supernatural intervention, or something shining light into our hearts of darkness, we can’t make the changes Peterson calls us to. Sure, our hearts still know what light looks like, but the Bible says we’re slaves to darkness, not just capable of it. In Romans 7, the apostle Paul describes the human life – the human heart — the life following Adam and Eve — in ways Solzhenitsyn and Peterson might recognise from their experiences of reality, but is more pessimistic about our ability to make atonement for ourselves.

“For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out. For I do not do the good I want to do, but the evil I do not want to do—this I keep on doing. Now if I do what I do not want to do, it is no longer I who do it, but it is sin living in me that does it.

So I find this law at work: Although I want to do good, evil is right there with me.” —Romans 7:18-21

What liberates his heart is not self-help; not an axiomatic pursuit of heaven on earth, but God’s intervention, by the Spirit, delivered as a result of turning to Jesus and sharing in his death and resurrection.

What a wretched man I am! Who will rescue me from this body that is subject to death? Thanks be to God, who delivers me through Jesus Christ our Lord!… through Christ Jesus the law of the Spirit who gives life has set you free from the law of sin and death. For what the law was powerless to do because it was weakened by the flesh, God did by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful flesh to be a sin offering. And so he condemned sin in the flesh — Romans 7:24-25, 8:2-3

When he wrote to the Corinthians, Paul does talk about imitating Jesus, especially the death of Jesus, both in his first letter where he tells the Corinthians to ‘imitate him as he imitates Christ (1 Cor 11:1), and in his second letter where he says:

We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. For we who are alive are always being given over to death for Jesus’ sake, so that his life may also be revealed in our mortal body... Therefore we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen, since what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal. — 2 Corinthians 4:8-11, 16-18

This is Paul bearing the ‘weight of being’ — suffering, taking up his cross, not just to improve life in some temporary sense, but because our lives have eternal significance. You can’t extract a temporally significant ‘mythos’ from Paul’s writings without making him a crazy man.

His life — suffering as he carries his cross — is built on the hope not just of some sort of ‘heaven on earth’ — but because any taste of heaven on earth is a picture of the real and supernatural future won by Jesus. If Jesus wasn’t raised from the dead, Paul says we should eat, drink, and be merry (1 Corinthians 15:32)— there’s no point not inflicting suffering on others if there is no supernatural judgment for that evil. And any decision to suffer, to ‘bear the weight of being’ by imitating Jesus is only really possible and meaningful if Jesus’ victory over death and satan is for reals.

“The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God! He gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ.

Therefore, my dear brothers and sisters, stand firm. Let nothing move you. Always give yourselves fully to the work of the Lord, because you know that your labor in the Lord is not in vain.” — 1 Corinthians 15:56-58

John, who also wrote Revelation with its cosmic picture of reality, talks about the atonement of Jesus, and the example of Jesus (a big theme in his writing) this way:

This is how God showed his love among us: He sent his one and only Son into the world that we might live through him. This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins. Dear friends, since God so loved us, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; but if we love one another, God lives in us and his love is made complete in us…

This is how love is made complete among us so that we will have confidence on the day of judgment: In this world we are like Jesus. There is no fear in love. But perfect love drives out fear, because fear has to do with punishment. The one who fears is not made perfect in love.

We love because he first loved us. — 1 John 4:9-12, 17-19

For John, and for Paul, the writers of chunks of the Biblical text that Jordan Peterson appreciates so much — the imitation of Jesus actually has to be based on the real victory of Jesus over the burden of being — the defeat of evil, Satan, and death. But John and Paul both offer a picture of masculinity redeemed by the example of Jesus — a life of sacrificial love; bearing one’s cross to improve the lot of others and to fight against Satan by imitating Jesus… it’s just there’s something more on offer than a good or meaningful life now.

In Peterson’s mythic take on the Bible and its account for life in this world, we’re either archetypally on team Satan, or team Jesus; there’s no middle ground. The heroic life is the life imitating Jesus; and making atonement by sorting ourselves out. As we live we’re either bringing heaven or hell. The Bible’s mythic idea that helps us understand the stories we participate in as people is also that you’re either team Serpent or team Jesus But fundamental to any victorious or heroic life in the Bible — and the reason to take up one’s cross — is that Jesus destroyed the serpent so we don’t have to, and our nature is liberated by participating in the life of God as his Spirit dwells in us — because we have been atoned, or literally ‘made at-one’ with God such that our lives reflect the lives we were made to live in the world; to be able to begin putting the world right our hearts must first be changed from above. There’s nothing more mythic in the Bible than the vision of life in this world offered by John in the book of Revelation; there be dragons.

And I saw an angel coming down out of heaven, having the key to the Abyss and holding in his hand a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the devil, or Satan, and bound him for a thousand years. He threw him into the Abyss, and locked and sealed it over him, to keep him from deceiving the nations anymore until the thousand years were ended. After that, he must be set free for a short time. — Revelation 20:1-3

The same bit of John’s ‘apocalypse’ — literally his revelation about how the world really is — tells the story of the end for Satan, and those humans who follow his archetypal way of life (and so become beastly rather than human).

“They marched across the breadth of the earth and surrounded the camp of God’s people, the city he loves. But fire came down from heaven and devoured them. And the devil, who deceived them, was thrown into the lake of burning sulfur, where the beast and the false prophet had been thrown.” — Revelation 20:9-10

We don’t defeat evil; God does. To try to extract some mythic ideals from the Bible that somehow we must take responsibility for our own redemption, atonement, and restoration, apart from divine intervention just doesn’t work; you can’t secularise the message of the Bible without turning it into superstitious nonsense.

A buffered — but haunted — view of the Bible or an ‘enchanted’ true myth?

Peterson treats the Bible seriously as a human text; a naturally emergent document that offers, in his mind, the best account of life in this world. As we read Peterson’s often brilliant engagement with the feelings and desires under the surface of the Biblical text — and he’s a keen observer of the human condition — it pays to remember he says, of the story:

“The Biblical narrative of Paradise and the Fall is one such story, fabricated by our collective imagination, working over the centuries. It provides a profound account of the nature of Being, and points the way to a mode of conceptualization and action well-matched to that nature.” — Page 163

But what if is more than just a human product?

What if there’s more to the world than just natural accounts for the nature of being?

It seems the jury might actually still be out on this question for Peterson, and we might be getting, in 12 Rules something more like provisional findings on the basis of how he currently understands the richness of the text. He is truly blown away by the richness of the Biblical story; it’s wonderful to see him treat the Bible with seriousness and a certain sort of respect; though it’s ultimately a respect for a sophisticated human reflection on human nature (though haunted by the idea there might be something more to it). In this video he says some pretty profound things about the nature of the Bible.

“I’m going to walk you through the series of stories that make up this library of books known as the Bible. Because it presents a theory of redemption that in a sense is emergent. It’s a consequence of this insanely complicated cross-generational meditation on the nature of being. It’s not designed by any one person. It’s designed by processes we don’t really understand. Because we don’t know how books are written over thousands of years, or what forces cause them to be compiled in a certain way, or what narrative direction they tend to take… now one of the things that is strange about the Bible, given it is a collection of books, is that it actually has a narrative structure. It has a story. And that story has been cobbled together. It’s like it has emerged out of the depths. It’s not a top down story, it’s a bottom up story. And I suppose that’s why many of the world’s major religions regard the Bible as a book that was revealed, rather than one that was written. It’s a perfectly reasonable set of presuppositions that it’s revealed; because it’s not the consequence of any one author. It’s not written according to a plan, or not a plan that we can understand, but nonetheless it has a structure. It also has a strange structure in that it is full of stories that nobody can forget, but also that nobody can understand, and the combination of incomprehensible and unforgettable is a very strange combination, and of course that combination is basically mythological.”

There is a sense, I suspect, that he might be haunted by the hope that the story of the Bible is as C.S Lewis described it ‘true myth’. In Lewis’ essay Myth Became Fact, he makes an interesting observation that I think explains why Peterson resonates so deeply with so many Christians; it’s because he appreciates the mythic quality of Christian belief, he sees it as ‘mythically’ true. Peterson is just the latest in the tradition of Lewis’ friend Corineus, addressed in this essay, who believe (like Nietzsche):

“historic Christianity is something so barbarous that no modern man can really believe it: the moderns who claim to do so are in fact believing a modern system of thought which retains the vocabulary of Christianity and exploits the emotions inherited from it while quietly dropping its essential doctrines.”

He wants to keep the mythic power of Christian archetypes, without the substance. Lewis, is seems, was also a fan of Jung, for what it’s worth. Lewis points out that by keeping the myths of Christianity and ‘aiming up’, Peterson is asking people to take the hard road, one that goes against much of our nature:

“Everything would be much easier if you would free your thought from this vestigial mythology.” To be sure: far easier. Life would be far easier for the mother of an invalid child if she put it into an institution and adopted someone else’s healthy baby instead. Life would be far easier to many a man if he abandoned the woman he has actually fallen in love with and married someone else because she is more suitable.

For Lewis it was the mythic quality of Christianity that gave it its appeal and its power. He’d, I suspect, be optimistic about the trajectory Peterson is on in wanting to affirm the mythic value of Christianity:

“Even assuming (which I most constantly deny) that the doctrines of historic Christianity are merely mythical, it is the myth which is the vital and nourishing element in the whole concern… It is the myth that gives life.”

Part of the appeal of Peterson, and his helpfulness (where it can be found) is that he is someone who truly believes that the mythic aspects of Christianity are truth (even if they are purely human creations). Lewis said:

A man who disbelieved the Christian story as fact but continually fed on it as myth would, perhaps, be more spiritually alive than one who assented and did not think much about it.

And this, I think, explains the phenomenon that for me, at least, Peterson (who sees a unifying narrative of redemption in the Bible centred on the cross) is a much more compelling (and useful) reader and commentator on Genesis than people who want to make Genesis do science.

But he’s missing something vital.

The key for Lewis, as it was for Chesterton, is embracing truths that appear to be furious opposites — embracing the truth that Christianity is both myth and fact. For Christianity to work mythically to offer redemption it has to be true. For it to give us a pattern of life not just for masculinity but our humanity, a pattern that would change and challenge even the wealthiest, most dominant, man (and the patriarchy) in such a way that it could truly bring a taste of heaven on earth, Jesus has to not simply be an archetype, but a real figure; a case where the supernatural world broke in to the natural, to deal with a real cosmic enemy and to substantially change our hearts, bringing light into darkness. Which is exactly how C.S Lewis came to understand the story — from a deep appreciation of myth, and here’s hoping this happens to Peterson and his fans too.

The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact. The old myth of the dying god, without ceasing to be myth, comes down from the heaven of legend and imagination to the earth of history. It happens-at a particular date, in a particular place, followed by definable historical consequences. We pass from a Balder or an Osiris, dying nobody knows when or where, to a historical person crucified (it is all in order) under Pontius Pilate. By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle. I suspect that men have sometimes derived more spiritual sustenance from myths they did not believe than from the religion they professed. To be truly Christian we must both assent to the historical fact and also receive the myth (fact though it has become) with the same imaginative embrace which we accord to all myths. The one is hardly more necessary than the other.