We had our first semi-major technological fails in our digital church experience this morning. A major fail would’ve been an electrocution or some costly equipment blowing up. This was minor league stuff relative to that — there were some issues around audio sharing of a pre-recorded component of our time together. Our service time was certainly not professional or polished this morning; and while I felt a degree of shame and embarrassment (some of our audio issues were a result of me accidentally muting our video when I muted my mic to ask my kids to be quiet), I’m reminding myself of the principles that have us where we are. I’m writing this as catharsis because of how much the tech fails grated on me this morning; and as a reminder that this is the path I think we should be committed to as a church community.

Watching the conversation around my tech-fail mea culpa post on Facebook, and the steady stream of churches and ministers promoting their live streams on my newsfeed has reminded me of the importance of principled decision making in this strange period. As an aside, I reckon close to 95% of the posts on my Facebook feed are churches advertising their online services. My cynical hot take: Facebook finally has a use for church stuff in its algorithm now that it’s the platform for church connectivity and can make some dollars.

I’m not a luddite. I have a smartish home. I have a coffee machine I can turn on with voice commands. My kids are listening to audio books in their bedrooms because I’ve allowed a multi-national surveillance capitalist company (two actually) to have a presence in our home in the form of speakers with built in microphones. Technology always involves trade-offs. Go read some Neil Postman, especially Five Things To Know About Technological Change or about Marshall McLuhan’s Tetrad of Media Effects for more on this (and more on McLuhan’s Tetrad below). But I’m worried that our principles as church leaders in this crisis are perhaps not as well informed as they should be.

This event — the shutting of church buildings and practice of physical distancing — will be disruptive for churches; especially because of how we’re now introducing technology into our ecosystem in new ways (though not totally novel, online churches have existed as concepts and entities for years). This will be potentially disrupt churches in the same way that Uber disrupted the cab industry, and AirBNB the hotel industry. It could also be that we use this disruption to re-invent our practices — but that will either be a principled re-invention or a pragmatic one.

Here are some of the principles, some theological, some practical, and some technological/media ecological that have shaped how I’ve approached this time in our church family.

I’m curious to hear other principles driving other forms or technological methodologies, especially as I think the period ‘disruption’ is going to be forced upon us (rather than the ongoing effect of these changes) is going to stretch on for some months.

Principle 1. Church is the gathered people not an event.

One of the greatest challenges for the church today is a slipping in to the habits of consumerism. We will resist forms of church that have us see church as a service that produces resources for my benefit or consumption.

Principle 2. Pandemics are not a reason to panic.

The universal church, those we are Spiritually connected to by the Holy Spirit and our shared belief in the Gospel of the Lord Jesus, and commitment to Jesus as king, has lived through many crises and pandemics, and has actually thrived in such times historically because where others act selfishly it has acted selflessly — followers of Jesus have walked into rather than run away from times like this.

Principle 3. Pandemics are not ideal; nothing about this time has to be perfect. We have to be gentle with each other and have low expectations.

The disruption happening here will mean non ideal experiences of church as we grapple with the very non-ideal experience of life. This isn’t a time for the pursuit of self-improvement and excellence, but for being held together by God and in the hope of the Gospel.

These non-ideal experiences are happening in the midst of a crisis that will take its toll on our community in various ways; economic, emotional, spiritual, need to mean we focus more on grace and relationships than results; and our priorities need to be firmly established and at the heart of our efforts.

Good enough is good enough. Not good enough is also good enough. This is especially true when coupled with principles 6 and 7.

Principle 4. Our priorities in a crisis are set by Jesus. Especially by his clear commands to his disciples.

Our priorities are that we as a church draw closer to God, closer to one another, and so are in a position to better serve our neighbours should the worst case scenario happen. This is how we apply Jesus’ two greatest commandments to this epidemic.

Principle 5. Media (as the plural of ‘medium’) are not neutral. The medium is the message. The forms we choose for church gatherings will be formative (and maybe permanently disruptive).

Screens are a medium or form that typically mediate content to us as consumers — especially now in the age of streaming (eg Netflix). The more our production values and content feels like Netflix the greater the impact of this medium will be on our message.

Because of the legislative framework we’re operating in (and because it’s just the loving thing to do to limit physical interactions in this time) we either have to use screens, or invite households (whether families or other mixed households) to operate alone. We can use screens to distribute content and we can use screens to maintain relationships. How we approach screens will show where our priorities lie here, which will reveal what we think church is and is about.

Principle 6. We will prioritise the relational over the distribution of content via screens.

This isn’t a dichotomy. Content matters. Our unity is built on our shared beliefs, that come from our shared story. But it is also a unity that comes from the very real work of the Holy Spirit who unites us as a community — as a local church and in the universal church. The local church is a particular expression of the Body of Christ; our services can either express something of the body, or give incredible prominence to the visible parts of the body (where Paul tells us in 1 Corinthians 12 that the not as visible parts of the body are worthy of the most honour).

In real terms for us this has meant not focusing on technological excellence, or production values, or livestreaming a picture perfect production with multiple cameras and a sound desk. There’s a sacrifice being made in our production quality. We don’t have a flash kids program with content for kids to digest. Instead, our kids church team are having a face-to-face video chat with two groups of kids (older and younger) and inviting the kids to speak to them and to each other in that forum (with two leaders, parental consent, etc for child safety compliance).

We’ve prioritised interactivity on Sundays over a shared downloading of content. I’m pushing us towards meeting just in our Growth Groups some Sundays to enable more people to be directly involved in sharing in the task of the body (Ephesians 4). I’ve ‘preached’ once in the last three weeks (a modified sort of talk, shorter because of screen limitations), another member of our community preached last Sunday, and this week we had a mini-panel where a husband and wife team delivered a pretty great package on Genesis 1 and how we live in a world where the ‘heavens’ and ‘the earth’ are overlapping realities, followed by a Q&A time. Each Sunday we’re spending time in our Growth Groups discussing the passage and talk.

Principle 7. We will bring a social media mentality with a push towards the local village not the global one.

‘Broadcast media’ where a central authority reproduces content to the masses (think Television) is an historical anomaly. It’s time came with the printing press, and the invention of radio and television, and is disappearing with the Internet. Social media is pushing us to peer-to-peer content, changing the nature of authority for good or for ill. It also has the potential to pull us out of the local village and into the global — making us ‘peers’ with people we might never meet. The ‘social media’ disruption of church in the era of “the global village” might serve to annihilate time in the way C.S Lewis said the car annihilated space (meaning we’re less limited to a local area as embodied creatures). This would look like tuning in to church services with a virtual presence that you will never attend with your physical presence. This might be like going on a virtual tour of a museum, gallery, or zoo. It’s very easy to do. But this isn’t a substitute for the local church, even if it is an expression of the global church. It’s also something that can feed our sense that church is a product to consume, that we should make that consumption decision not based on the people God has gathered us together with (locally and in a community that comes together), but based on the quality of content produced (including the quality of the preaching, and the production values/schmickness of the service).

I don’t want church to be a thing you watch from bed in your pyjamas. That is a disruptive norm that will be diabolical beyond this shutdown.

I don’t want church to be a thing you pick to download, from a global smorgasbord of excellent Bible teachers with a high-powered band and schmick AV.

So though we are more dependent on technology, I want to push further away from broadcast style technology (though I did purchase a new microphone to make sure people can hear what we say from our family’s side of our screen). I don’t want church to be a ‘livestream’ or a ‘broadcast’ but a social gathering (which has pushed us towards Zoom, and as much as possible the live delivery of content where we can see each other’s faces and have multiple contributors).

Principle 8. If this period disrupts us I want this disruption to be towards our underlying principles, not away from them, and to be cultural rather than technological.

I’d like to be disrupted towards greater connection with God and his people, towards greater love for neighbours, and to a model of church built on participation not consumption. This means being careful what technology we embrace, and how much we embrace it. Careful to think about how the mediums we use become part of the message we receive; and the forms we adopt become formative.

One place this is a live issue for me is in the discussion that is happening more broadly about whether the sacraments (for Presbyterians that’s baptism and the Lord’s Supper) can happen virtually. I don’t think they can. But I would be happy for us to be disrupted towards a truer priesthood of all believers, and even for this epidemic to disrupt our idea that the ‘household’ is a nuclear, biological, family — that means too many of our community are facing social distancing in physical isolation. I don’t think we can share in the Lord’s Supper via Zoom, theologically speaking, but I do think households can participate in the meal instituted by Jesus, where he is spiritually present as we break bread, at their tables over a meal. It’s interesting that the last (and only) time the Westminster Confession of Faith was amended by the Presbyterian Church of Australia was around the emergency conditions of a World War in order to allow non-ministers to conduct the Lord’s Supper… That’s good and lasting disruption right there.

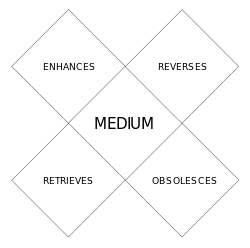

Marshall McLuhan’s Media Tetrad is this model that says whenever a new technology or medium is introduced into a system it impacts that system in four directions.

It enhances some capacity we have (so video calls allow us to see into places where we are not). It makes some other technology obsolete (the way that emails made letters much less necessary, and video calls make telephone calls essentially obsolete). It retrieves a capacity we might previously have lost (so video calls add, for example, a face to face dynamic and non-verbal communication cues, where print and telephone removed those). And it reverses something when pushed to its natural limits, as in, it ultimately pulls us away from a previous norm (so video calls taken to an absolute might give way to virtual reality and the idea that we don’t need a bodily presence anywhere to do anything real.

There are real risks for churches here if there is a technological disruption to what we think church is, based on how we practice church. We might enhance how easy it is to go to/consume church because we can now watch it from bed in the comfort of our pyjamas, without having to truly see other people, or enhance some ability to produce higher quality stuff (because we can pre-record, edit, and post-produce). We might retrieve participation of more than just professionals through some technology choices (like using Zoom), we might even see one another (digitally) much more often in this period than we once met in the flesh. But in the ‘reversal’ that is really where the disruptive power of technology kicks in, we might convince ourselves that these other changes are good, both pragmatically and experientially. That they, when coupled with the conditions of toxic churchianity, expand our reach, grow our platform, and make our consumption more frictionless, and charting the way back to messy, embodied, local church might be more difficult than we think.

I’d like our church community to emerge from this healthy; having loved God, loved one another, and loved our neighbours well, and having pushed further into a culture (structures and practices) that means that our ‘mediums’ support our message (the Gospel). We’ve often talked about being a church of small groups, not with small groups. I’d like that to become real. I’d like to decentralise power/control from me and my voice, to a community that genuinely acts as the body of Christ (recognising that I, and others, have been appointed by God, and by our community, to have particular roles in the life of that community). I’d like us to be practicing the spiritual disciplines, including rest and play. I’d like us to be doing this as a way of pushing back against the prevailing values of our culture and the way they have infected the church; the way we’ve co-opted forms and solutions from the world of business and entertainment so reflexively, the seriousness of modern life, our truncated moral imaginations that lead us to pragmatic rather than principled solutions to problems (utility over virtue), and the disenchanted ‘secular’ frame we live in which is, in part, created by the ecological impacts of technology and the way that human ‘technique’ has become our solution to any dilemma, in the absence of prayer, and the way technology dominates our social imaginary so that we think about reality through a technological grid — expressed through our dependence on technology, and our imagined solutions to this period being largely technological are symptoms of this, and that goes for how we’ve jumped to the solve problem of not being able to meet together as the church. Technology is the architecture of our action and our belief; it’s forming us as we form it). We desperately need disruption and a push of the reset button. Note: My friend Arthur wrote this Twitter thread the other day outlining just how much stepping out of ‘Babylon’ is required in order for us to see the way Christianity does have something profound to say about the crisis moment being revealed in the midst of this pandemic. What I’m calling ‘toxic churchianity’ is really just the impact of what he calls Babylon on church culture. That needs disruption so that we can be disruptive.

So I’ll take messy church with technology glitches that we’re all experiencing simultaneously, in a weird ‘meeting’ on Zoom broadcast from our lounge room while the kids are going nuts, over a schmick, faultless, production beamed, or streamed, into loungerooms, or shared in online ‘watch parties’ experienced asynchronously, because though I’m praying disruption happens for the church, in this moment, I’m hoping the disruption will push us back towards our principles, not into something disfigured and deforming.