This was a sermon preached at City South Presbyterian in 2024. You can listen to the podcast here, or watch it on video. Some of the block quotes were on screen and summarised but have been included in full.

If Being Human was about who we are (or whose we are) and Before the Throne was about ‘where we are’ — on earth but also ‘raised and seated with Jesus in the heavenly realm,’ this series is about how we live in time and space; how we inhabit the world as humans, and as followers of Jesus.

The idea is that if we want to be disciples of Jesus — people being formed by him because his love and Spirit are transforming us — this happens as we inhabit time and space, and this happens at the level of our habits.

Forming these habits that form us is tricky, because the world we live in — our habitat — has been set up by humans to deform us with an entirely different set of habits; leading us to worship entirely different gods and so forming different habits in us; habits we have to combat and unlearn.

We are not always good at spotting our habitat and how it shapes us. In fact, often we do not think about habitats or habits. We can slip into the modern, western way of thinking where we do not really reckon with the power of habits — unless we want to change to be “super successful,” where we might buy a self-help book about ‘atomic habits’ or ‘the power of habit.’

Right from school we are taught that we change — we are formed — by thinking the right thing; having the right ideas so we can choose how to live. This is true for how we think of church too — we emphasise content, listening to sermons, reading the Bible, talking about ideas — hoping education about God will transform into our character.

I know we have been combating this idea as a church for a while; thinking about what it means to live before the throne, and to see God’s kingdom on display at the table as we eat together in unity as a family or household united in Jesus. But this has been stuff we have thought about. What does it look like to change the architecture of our lives — our habitats and habits — to reflect these ideas? To move ‘ideas’ into ‘habits’?

And how much is the habitat we live in — our city, our homes — priming us towards different habits; forming us to worship different gods? There is an idea in our world that religion is a private thing best left for church spaces or your home — where the architecture of our world would be “neutral” — nothing like the Athens in our reading — and not like somewhere like Sri Lanka.

If you were the apostle Paul walking through Kataragama last year you would have recognised a community that is very religious — and then you would have seen a procession of elephants getting out of control and trampling the crowd, injuring thirteen people.

This will be a bit of a parable for us this morning. I think there are two principles to pull out: all space is set up to produce behaviours — habits — and these habits are a kind of worship that form and shape us. It is just easier to see how that is true in the stomping foot of a living elephant than in the architecture of our lives. We can try to stop that impact by grabbing the elephant by its tail — but it is better to be consciously deciding where that formation is happening.

Let’s jump into Athens, where the religious architecture is made of stone rather than flesh, and set the scene by looking at the end and beginning of our reading. At the end, Paul has given what looks like a pretty compelling sermon to the council in Athens whose job it is to decide whether a god will get space in their assembly of gods — symbolised by the Parthenon, that massive building that still dominates the skyline in the city of Athens today.

When he is finished, there are a few people who are convinced to change the architecture of their lives; to alter their altars, so to speak. Some want to hear more, some believe, but it seems most of the crowd sneered (Acts 17:32). They are entrenched in their beliefs; their habits. They have been formed as worshippers of the gods of their city; their convictions align with the convictions carved into the architecture of Athens.

What Paul sees in the opening of our reading as he wanders through this city is that it is full of idols (Acts 17:16). I do not know if this is your experience when you wander down the Queen Street Mall, or Boundary Street, or West End, or in Garden City or your local Westfield — can you spot the architecture of these habitats and what it is designed to do to human hearts and minds? The trampling elephants?

It is more obvious for Paul in Athens because it was a city filled with statues and altars and temples — full of things designed to pull people away from the worship of Yahweh, the creator; to form them — or deform them. Paul’s heart is attuned to this, and to the impact of this sort of habitat. He is distressed.

He starts inviting people to meet the living God — he is preaching the good news about Jesus and the resurrection (Acts 17:18). He ends up with an invitation to the Areopagus, this council — and there is some evidence he crafts his speech according to the rules they used to accept or reject new gods as he speaks to them — but he is also drawing on his observations of their habitat.

“I see that you are in every way very religious”

— Acts 17:22–23.

Now, let us suspend for a moment our belief that our city is not religious; that religion is a private matter — and let us imagine that religion is about what we give our lives to; what we serve because it is what we see as ultimate and powerful. Let us take a moment to consider how our city’s architecture is just as contested and confusing as the polytheism of Athens, and how religious we still are. Our cities are full of monuments to human ingenuity — our capacity to shape the world using technology and technique; to money — banks and skyscrapers named after banks; our belief that education transforms — and so our universities, where the architecture is often similar to the architecture of the Athenian forum — and our belief that we can buy or consume our way to the good life, through pleasure and purchasing. This is before we get into the ground-level architecture of our own lives.

Athens, though, is so religious it has every box ticked — even an altar to an unknown god — which is an opportunity Paul cannot pass up. There is not much architecture in their city pointing to this God — no church buildings, and not many Christians living lives that model the gospel yet.

One of the criteria Athens had for introducing a god via this council was to address the question of what sort of physical architecture they would need — what sort of temple and altar and cycle of sacrifices. Paul challenges this category — not so much by saying “do not think about habitats,” but by claiming that the whole world is meant to be geared to the worship of its creator. The Lord of heaven and earth — the God who made the world — does not live in temples built by human hands (Acts 17:24–25). This is part of the game-changer that happens in the start of Acts, where God’s Spirit comes to dwell in humans who receive life from Jesus as his gift to us. This life is not a thing we earn through ritual; but it is a life that comes with new habits as we are transformed into living temples. We do not serve God the way a pagan god is served through sacrifices on various altars, because the living God has served us through his sacrifice. He is not a taker, like the other gods of Athens — but a giver — even to the Athenians who are not worshipping him. He gives everyone life and breath and everything else (Acts 17:25).

An Athenian believes their prosperity — if they have any — comes from the specific collection of gods they have chosen to serve; to worship; to sacrifice to — that their prosperity is earned through getting the mix right between their efforts — their habits — and what those efforts trigger as they engage in their habitats — these religious spaces. But Paul says everything they have is actually a gift from a God they do not even know, let alone worship.

Here are the key verses for our whole series. Paul says all nations — all the peoples of the earth, who have built all the cities of the earth — all our habitats — all people are made by this one God so that we might inhabit the whole earth. This is a throwback to Genesis and the idea of being God’s image-bearing people who are fruitful and multiply and fill the earth — and it is God who locates each nation — each person — in time and space, marking out the time and the space we will inhabit (Acts 17:26) — with a purpose — so that we would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him (Acts 17:27–28).

Maybe this is why idols are so distressing for Paul — they get in the way of this purpose; they stop people being truly human; imaging the God who made them. These images and the habits that come with them — the habitats we build around idols — stop us inhabiting the world the way God created us to; they deform us; they keep us from reaching out for him and finding him; they blind us to how proximate he is, and even how much he wants us to know the source of our life and breath and being.

And look — maybe you are here with us this morning still searching; maybe you have come along to church because you have noticed that the architecture of our city still includes these spaces and these communities offering some sort of answer; some sort of meaning — and pointing to some sort of God amidst all the other choices you have. I hope you can find meaning and purpose with us — not in us — but in God — the God who wants you to find him, and who gives life.

Maybe you are here this morning as someone who is a Christian but you feel this gnawing sense; this lack of meaning and purpose; or like you are caught between so many choices; so many options; a habitat that is confusing and a set of habits that do not align with who God wants you to be — sins, addictions, wired-in responses to the world based on what you have done, or what has been done to you. This series is an opportunity to take a fresh look at the architecture of your life and to let God do some reforming.

Paul’s message in Athens is a message for us — whether it is about our idols, what we look to for meaning or purpose; or our self-help — our self-actualisation or self-idolisation — where we work on our self-image through sacrifice, even harnessing the “power of habit” out of some legalistic desire to be better.

We are God’s children — this is all humans, not just Christians — and so we should not think that being more human is a matter of human design and skill (Acts 17:29), whether that is idol-building or harnessing the right power of atomic habits. It would be easy, as we talk about inhabiting time and space and the way our habits form us, to become Christian legalists who think nailing good works is a path to the “better us,” the “truer us” — to focus on self-improvement and make us the drivers of our destiny. This is a tension Christians have grappled with for the entire history of the church.

That is not the gospel though. The gospel liberates us from legalism, and from false worship, and from self-reliance because it liberates us from human rule — whether the rulers of the cities we live in, the architects of our behaviours and our slavery to sin and to deforming powers and deadly idols — or just our need to master ourselves through skill — and places us as children who are invited to learn life from our heavenly Father and from his Son — our king — Jesus. This comes with different habits, and it helps us to think about the architecture of our life differently — but hopefully in a way that is liberating and life-giving and re-humanising and good for us, rather than destructive — because we are pursuing what we are made for; not on our terms by discovering the “true self” within and never being sure if we have quite understood ourselves — but by understanding the nature of the divine being in ways that mean we begin to reflect his life in his world.

There is some fun stuff in the background of this Acts sermon around the nations and their gods — and God overlooking ignorant worship (Acts 17:30). I will not go super deep into it, but there is an interesting thing where, if you dip into the Old Testament, the nations do not tend to be condemned for idolatry — they have been given to powers and rulers who are not Yahweh — and you can kind of pinpoint this moment in the story to the story of Babel when the nations are given their boundaries (Genesis 11:9), or to this idea in Deuteronomy that the nations have been given to other powers — “sons of God” — while Israel have been marked as God’s children (Deuteronomy 32:8). The story, though, is that all of these nations are human; all created by God, and that God is greater than all these powers one might worship. In Jesus — and his victory over sin and death and Satan and these powers — God now commands all people everywhere to repent (Acts 17:30); to come back to him and find their humanity in his kingdom; in reflecting him. As we saw in our last series — this is the turning point in the Lord of heaven and earth’s plan to bring heaven and earth back together as one.

This day — this future — is where he will judge the world with justice through the man he has appointed — Jesus — the one raised from the dead (Acts 17:31). This day — this future — is now the guidepost for life inhabiting time and space; a reason to seek out and perhaps find the God who sought us in Jesus.

And if we are those who hear Paul’s message and believe, this comes with a new architecture; because the architecture of the city of Athens — its idols — is a dead end and will not last. You have to wonder what life was like from here on for Dionysius, who was a member of this gatekeeping council, or Damaris (Acts 17:34). Luke, who writes Acts, often does this thing where he names people along the way, where I think he is both indicating they are a source in his investigation and description of the life of the church, and that they are people in these church communities; living, breathing witnesses for his first readers. You can imagine Dionysius going home and cleaning the idol statues out of his home, and maybe renouncing his job deciding which idols do and do not get worshipped, and Damaris rethinking who she turned to in prayer to secure her fortunes — and even what “fortune” looked like — as she worked out how to serve a living God of heaven and earth, not a statue contained in a temple. That this came with new habits and a change of habitat as they discovered what it means to live as children of God; and, hopefully, a sense of liberation from the need to get everything right in order to live.

Their challenge in their city is our challenge in our city: inhabiting God’s world as God’s children. Inhabiting our time as the time God has appointed us to exist in — in history, within the boundaries of our lands. Inhabiting time and space is not a choice; it is a given — given to us by God.

Habits are not just atomically powerful tools for transformation; they are not just areas for legalism and self-actualisation or self-improvement; they are also, to some extent, givens. We are creatures of habit; shaped by the habitats we operate in and our vision of the divine, and what we work towards and serve with our bodies.

The architecture of our lives — the space we inhabit — whether our city, like Athens, or our homes, and how we structure our time — is full of idols. It is geared to produce habits and rhythms, and if we are not deliberate in our choices, or fortunate enough to occupy spaces deliberately shaped to form us in godliness by others, the habitats we operate in deform and trample us like elephants.

In Romans, Paul talks about this architecture as the patterns of this world, and he invites worshippers of Jesus, as we engage in worship — the habitual use of our bodies — in view of God’s sacrifice, his gift of life for us, to not conform to the trampling elephants of this world, but to be transformed by the renewing of our minds (Romans 12:1–2). For Paul, this is a product of God’s Spirit being at work in us, transforming us into the image of Jesus.

It is this idea of our minds I want to zero in on today as we begin this series. Preachers get into big trouble trying to sound like experts on brain science — in part because the science itself is always developing and is pretty contested because we are complicated.

One study suggested just using a picture of a brain scan in a news story — and probably a sermon — means you can make just about anything seem plausible; that the image provides a physical basis for something abstract, and that we tend to want simple explanations of cognitive phenomena — brain stuff.

“We argue that brain images are influential because they provide a physical basis for abstract cognitive processes, appealing to people’s affinity for reductionistic explanations of cognitive phenomena.”

— McCabe and Castel, ‘Seeing is believing: The effect of brain images on judgments of scientific reasoning’

But another study debunked this one; they tried to replicate the experiment and found that brain images exert no influence on people’s agreement, but that “neurosciency language” can make bad explanations seem better.

“We arrive at a more precise estimate of the size of the effect, concluding that a brain image exerts little to no influence on the extent to which people agree with the conclusions of a news article.”

— Michael, Newman, et al, ‘On the (non)persuasive power of a brain image’

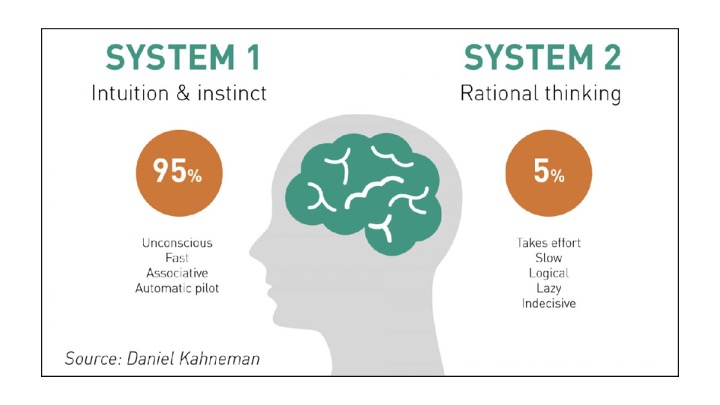

With all that in mind — and with us thinking about transforming our minds as we inhabit time and space — Daniel Kahneman was a Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and economist who wrote Thinking, Fast and Slow about how our brains work.

He brought in this idea of “System 1” and “System 2” thinking. System 2 thinking is the kind of stuff we aim at in churches when it comes to formation — thinking; rational decision-making where we are conscious and applying principles of logic and agency.

He reckons System 2 accounts for about five percent of our actions, while System 1 does most of the work — it is our intuition and instinct; what we do on autopilot.

Jonathan Haidt is another psychologist — he is going a bit viral at the moment because of his book on social media and anxiety — but before that book he wrote a couple of books about how our brains work and how they shape our moral actions and judgments.

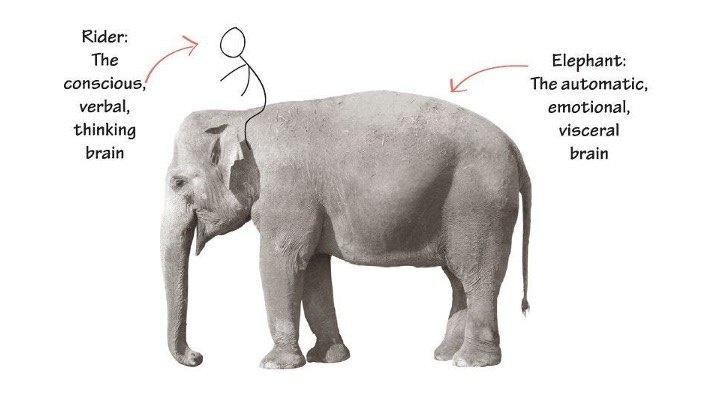

He used a metaphor that is a bit easier to grasp for System 1 and 2 thinking: the rider (System 2) — the conscious part of our brain — and the elephant (System 1) — the automatic part — where the idea is that it is nice to think that the rider is in control; that we steer our elephants towards goodness and truth, but really so much of who we are, and what we believe is right and wrong, happens at the level of our emotions and guts.

I reckon this is true of our discipleship too — the question of what god we serve and how we live that out. I do not know if this is your experience with sin, but I reckon I can be believing, in my rider-brain, all the truths I get up and preach and read and speak, while at the same time feeling pulled again and again into anger and lust and all sorts of patterns of this world and passions of the body — ruts, addictions, bad habits — that deform me and harm others without conscious thought.

The battle to be in control feels like a battle to steer an elephant before it tramples me, or others — trying to grab its tail while it is stampeding.

So here is my theory: the architecture of our idolatrous world is set up to feed our elephants and steer them in destructive ways.

Idolatry and worship work not just on the conscious mind, but our whole minds — our intuitions and instincts. These are the patterns that need renewing and transforming, not just our thinking. While it is great to get our brains in control and try to steer the elephant, maybe we also need to work at training the elephant with a new architecture — to pull us towards godliness; to keep in step with the Spirit so God produces fruit in us, rather than us producing destruction.

One of the ways we feed this elephant is through habits. It used to be a criticism of churches that did lots of ritual stuff that, over time, the repetition became less meaningful — but I wonder if that is because it moved from being conscious to automatic, and whether we live in a culture that puts a disproportionate amount of importance on the conscious bit of our brains because we like the idea that we are masters in control with the right information.

The Other Half of Church — a book about brain science and how we think about church and discipleship — is worth grabbing if you are interested in thinking through some of this.

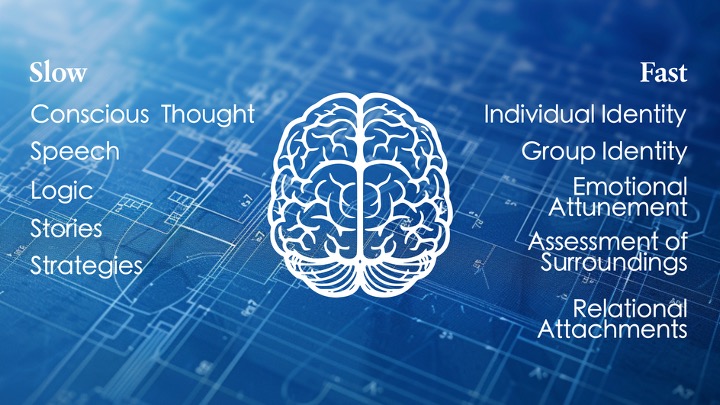

We will dip into it throughout the series. The authors take the same model — the slow and fast parts of our brain — and suggest we have built churches to cater just for the bit that is impressed with good arguments and logic and stories and strategies, at the expense of shaping our intuitions and relational depth.

They reckon this part of the brain — the elephant (though they do not use Haidt’s model) — is shaped through attachment; through schooling our emotions and our intuitions by feeling secure, and connected, and attached to God — like children to a loving, nurturing parent — and in a community where we are being shaped and nurtured.

The problem is that often how we approach church is about our rider; the slower system — and we live lives that are hurried and almost constantly on autopilot — another function of our habitat. We can try to put the rider in charge but, to do that, we need to be slow and unhurried, and not anxious or panicked. That elephant stampede happened when loud noises startled the elephants.

“We were pursuing discipleship by focusing on strategies centered on the left brain and neglecting the right brain.”

— Jim Wilder, Michel Hendricks, The Other Half of Church.

So this series is an invitation to slow down, to be deliberate; to try to get the rider in control — to use our time and space to make conscious decisions aligned with the truths we believe, but also to bed down habits and security into the elephant so it does not get panicked and crush us or others; so we automate godliness rather than sin.

It is to discern some of the habitats we live in — the idols in our architecture — the patterns of our world — and their deforming power, and to make decisions about our habitats and our habits. It is to take up this search we were made for; reaching out for and finding the God who lives; who is in heaven; who is not destructive like a rampaging elephant, but a generous giver — who gives us life and breath and everything else — because we are his children (Acts 17:28). When we find him we find a good Father, who is also seeking and reaching out for us, delighting in a relationship with us.

Repenting means turning from the gods and patterns — the elephants — who stomp us into their image, and returning to him as our Father, the giver of our life, and being shaped accordingly. It means restructuring our lives — how we inhabit time and space — as those who have found life with him.

Justin Earley has written a couple of resources we will look at this series for how we live together in time and space. In his book about building habits of purpose for an age of distraction, he talks about realising how the shape of his own life was a bit like Athens. His house might have been decorated with Bible verses and imagery — Christian content — but the underlying architecture of his habits, his habitat, was like everyone else’s.

Repenting involves transforming not just the decorations in our life, but our structures and rhythms — how we live in the place and time God has put us, with our bodies and our time, as children of God; knowing what he is like and experiencing joy through our attachment to him as those who can come before his throne.

“While the house of my life was decorated with Christian content, the architecture of my habits was just like everyone else’s.” — Justin Earley, The Common Rule.

When we are imagining what life might have looked like from then on for Dionysius and Damaris in Athens, I reckon it is safe to assume the pattern of the first church — its habits and habitats — might have shaped their lives. Those who repented and found life in Jesus devoted themselves not just to learning — shaping the rider through the apostles’ teaching — but to connection: fellowship with God and each other, the breaking of bread, and prayer (Acts 2:42). They met together as a rhythm; not just in the temple — which they could do in Jerusalem — but in homes, around tables, eating together, praising God, experiencing joy and security and connection (Acts 2:46–47). Inhabiting time and space together with God; learning to be like Jesus.

The final resource we worked through in small groups during this series was the Practicing the Way course. We used their material in Growth Groups — meeting in homes — where we are not just learning information, but experiencing this connection. We used this video as an introduction to assessing the architecture of our habits; trying to spot the way elephants are stampeding us.