This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 34 minutes.

You’ve heard about the State of Origin, well, in this section of Genesis, we’re reading about the origin of states, nation-states, to be precise. It turns out, in the Bible’s narrative, these entities are more connected than we might think; they’re part of the same family tree, even while they appear to be lifelong rivals.

In our last section of the Genesis story things were looking up. Noah resembled a new Adam, ruling over the animals — saving them, providing for them, releasing them to be fruitful and multiply. And like a priest, he was building an altar, making a sacrifice — a precursor to the atonement sacrifices made in the temple by a righteous representative. They were even on a mountain, a heaven-meets-earth space, where God promised not to destroy everything again, even though there’s a hint that nothing in the hearts of humans had changed.

In this section there’s even more Eden imagery at play. Adam, the man of the ground, placed in Eden, is replaced by Noah, the man of the ground, who plants a vineyard. It produces fruit, and Noah enjoys the fruit of his labours — too much. Like Adam and Eve, he encounters some trouble with the fruit in his garden, and he becomes unashamedly naked. He lies uncovered in his tent.

Now, Noah finds himself in trouble. But let’s just examine some of the parallels to Genesis 2 — where Adam and Eve were naked and unashamed; there was no risk. They were meant to enjoy the fruit of the garden. Noah does something dumb, but this is not a repeat of the fall here — he becomes the fruit, lying there, unable to act. Noah becomes a test for his sons. Sin is crouching at their door. Will they be like another ‘ground man’ — Cain?

Something super sketchy happens here, and there’s a bit of “wink-wink, nudge-nudge” happening. Ham fails. He “saw his father naked” (Genesis 9:22). We’re primed to see his actions as problematic because, when Noah’s sons are reintroduced, we get the sideways comment that Ham is the father of Canaan an historic enemy of God’s people at any time this story is being read as part of the Torah when it is completed (Genesis 9:18, 22). He’s the father of the Nephilim-sized enemies who pop up (Numbers 13:32). Genesis 6 should be ringing in our ears as readers. There’s a good case that behind this euphemism we’re reading the origin story of Canaan, and “seeing his uncovered father naked” is innuendo for something sinister. In Genesis 2, nakedness is neutral; there’s nothing to suggest that seeing nakedness itself is a sin; there’s something more happening. Ham is cursed because he does something wrong.

In Genesis 3, once sin enters the picture, coverings are first made by people, then by God as protection from our vulnerability to beastly predators who’ll take advantage of nakedness — a pattern maybe implied with the Sons of God ‘seeing’ human women that we see explicitly as David acts as a predatory Son of God and takes Bathsheba.

Ham’s transgression is a big deal; it’s a fall; he gets cursed as a result (Genesis 9:25). I’m not sure we’re meant to think he just had a laugh at his nude dad. There’s something going on where he is dishonouring, maybe even usurping his dad in a repeat of the sort of grasping evil that has led to a curse so far, it’s a pretty seedy origin story for Canaan.

Because when Leviticus — the same part of the Old Testament, by the same author, talks about uncovering people’s nakedness, well, here’s how the ESV translates these same Hebrew words in Leviticus 18:7: “don’t uncover the nakedness of your father, which is the nakedness of your mother” — and that’s a euphemism for sex. Then, Deuteronomy uses the same Hebrew phrase here in this verse — that says a man shall not take his father’s wife, or uncover his father’s nakedness. So later on, you read about Lot and his daughters, who get their dad drunk — in a sort of mirror of this story — to produce children who become the Moabites and Ammonites (Genesis 19:35-37). You can take all that with a grain of salt; but the parallels are there, and so is the law — even if it makes us feel a bit seedy, which is maybe an unfortunate play on words when we’re trying to follow the line of seed that will produce a serpent crusher; rather than the seedy, beastly humanity we see running around in the story.

But before we follow Ham, the father of Canaan’s line, we see Noah’s other two sons acting rightly. They act like God in the Garden, covering up Noah’s nakedness without bringing him shame. They go above and beyond to do what is right for their father. When Noah wakes up; he finds out what Ham has done, and acts like God, pronouncing a curse on Ham’s line (Genesis 9:24-25). Ham’s seedy line is not the line of seed. His line will be the lowest of the low; literally the servant of servants, like a serpent on its belly, and he gives a blessing to their brothers (Genesis 9:26-27). That will be a pattern that repeats in Genesis. It’s also one we’ve seen before; one brother receiving blessing and approval, while the other receives a curse because sin devoured him and made him a devourer. It’s these two family lines, God’s children and the serpent’s — a line of blessing, and a line of curse — continuing.

Shem’s really the one to watch — it’s a fun side fact that his name literally means “name,” especially because we’re going to see people keep trying to make a name for themselves… but he and Japheth are blessed, while Ham isn’t even named now; just his kid Canaan, and the nation his line represents in the story.

Then we’re told Noah dies (Genesis 9:28-29), and we get a long list of the generations of Noah’s kids in what gets called the Table of Nations (Genesis 10). This is how the Genesis origin story offers an origin story for all the people Israel knew or dealt with in their national life in the Old Testament.

It’s a weird genealogy because it’s very deliberately stylized; it becomes a sort of symbolic picture of all the people of the world — there are seven times ten nations — those numbers repeat all through the Torah — seventy nations. Everyone.

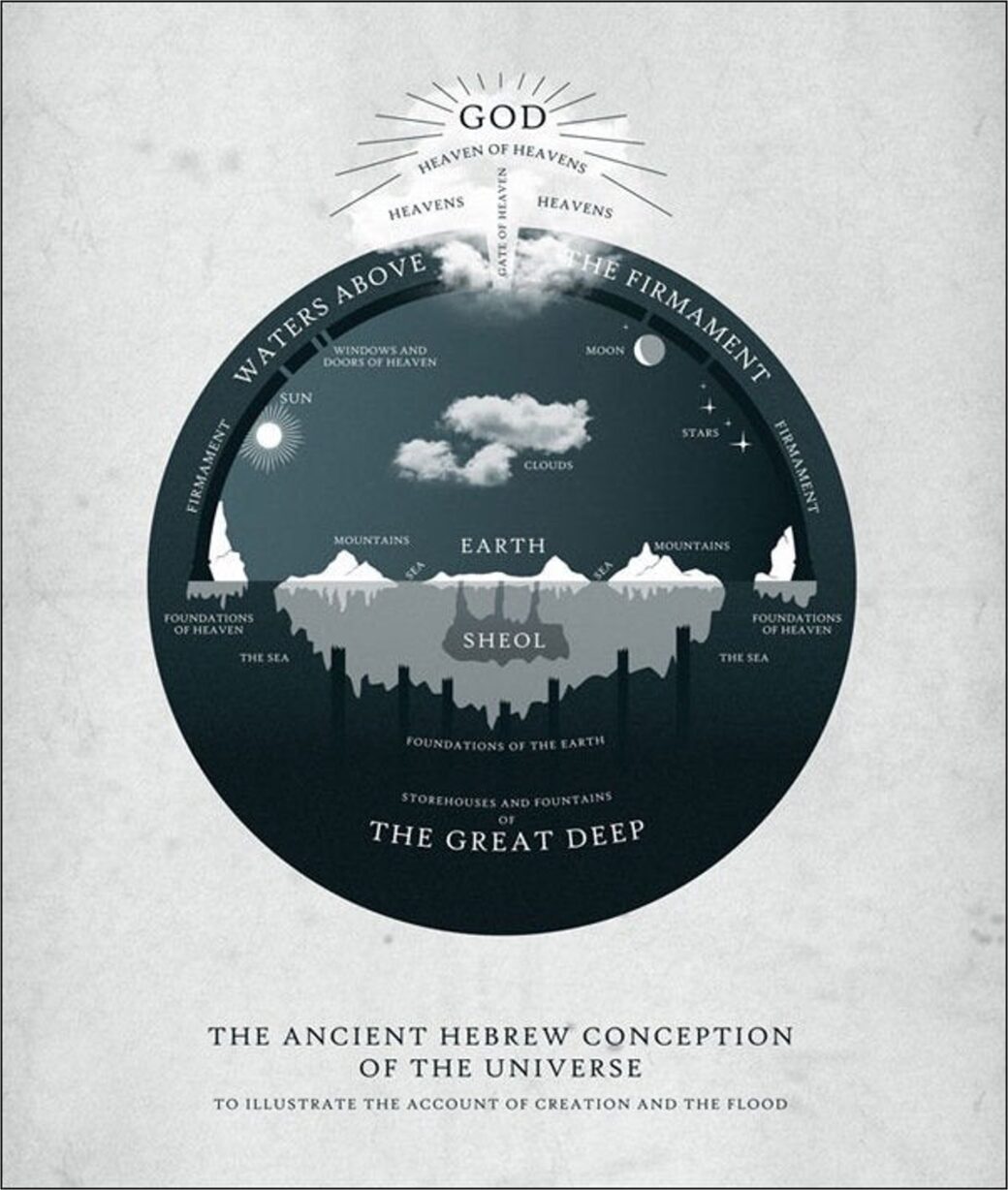

This section is bracketed with this statement that all the people come from this family tree. This origin story — like with Genesis 1 — is making the point that everyone under heaven, even Israel’s enemies who they might want to see as not human, everyone was made to perform the same function; to represent God; and everyone in the story comes from the same flesh and blood — the one humanity. We have the same breath of life in our lungs, and the same lifeblood pumping through our bodies by our hearts.

And we’ll see, in the line of Ham — we get the Bible’s origin story for Babylon; it’ll retell that story from a different angle in the story we look at next week, because it’s going to become a big deal in the Bible’s story.

In Japheth’s line, we get a whole bunch of nations, and then we zero in on just two of their sons — Gomer and Javan — to get a spreading out into other nations — and these nations will become pretty significant in the trajectory of the Old Testament story.

So, for example, Javan is the Hebrew word for Greece, and the others found coastal city-states of the Mediterranean. These nations are spreading, each with their own language… and there’s an interesting chronology thing going on here with the Babel story where these languages emerge in the narrative; this chapter foreshadows and provides some broader background for chapter 11.

Then we meet Ham’s kids — Cush, which is Ethiopia — then Egypt, where Israel spends time in slavery and captivity before the Exodus, Put, and Canaan — the giant enemies of God who occupy the land. In this line we meet sons and nations that share names with places watered by the rivers of Eden (Havilah and Cush, see Genesis 2:11-14). Presumably, the story is telling us that the life that flowed through Eden ultimately flowed out and watered the land and provided life where these nations would spring up from the ground after the flood. The other rivers — the Tigris and Euphrates — head into Babylon.

And that’s where we go next, from Ham, via Cush, we get the story of the founding of later, and maybe greatest, enemies of God’s people. Babylon and Assyria (Genesis 10:8-12), other than this bit, the Table of Nations is mostly a genealogy with a few bits of commentary thrown in, but we throw to story mode here, which makes you think this bit is at the centre of the narrator’s purposes.

We’re told some details about the founder of these later empires that throw back to pre-flood life, or patterns. Nimrod is a mighty warrior — just like the Nephilim — it’s the same in the Hebrew as the ‘heroes of old’ (Genesis 10:8, Genesis 6:4). This is a human who spreads bloodshed like Cain and Lamech and the Nephilim; a violent ruler, perpetuating the type of behaviour that caused the flood. He’s a warrior “on the earth” (Genesis 10:8); we’ve been set up to see earth as different from heaven, and as the domain for human rule as we fill the earth, and he’s filling the earth with violence.

His name comes to mean ‘mighty hunter’ because — even though animals have only just been given to humans as food, he’s a real good beast-master — a beast-killer (Genesis 10:9). It didn’t take long between God giving Noah and his descendants animals to eat — with the caveat that animals would fear humans — for Nimrod to give a reason why. This isn’t the sort of rule Genesis 1 pictures for humans over animals, it’s not how Noah cared for the animals. He’s an anti-Adam who builds violent cities instead of a garden (Genesis 10:10-12).

From there, we get the whole list of the people who will enslave Israel, or who they have to displace from the lands later, and a description of them spreading out into that land (Genesis 10:13-20).

Ham’s line isn’t going to be the line where the seed of the story we follow comes from — it’s a dead end filled with violent and grasping nations who get caught up in a cycle of violence, and who’ll violently oppose God’s kingdom coming. The beastly line of Ham produces Canaan and Babylon and Nephilim-like heroes like Nimrod.

And one of the points here — in this narrative — especially if you’re reading the story in one of these empires — is don’t be a Nimrod — there’ll be a tradition that expands from here that pictures God’s people as shepherds who exert mastery over beasts, but who care for animals as an analogy to how God cares for people, and of God’s people beating swords into plowshares — resisting these patterns. Not being like Nimrod and his bloody empires. Empires built on seedy sex — ‘uncovering the nakedness’ of others, and bloody violence; empires that consume.

It makes you wonder how much we participate in systems of violence in our cities and empires — how much we benefit from Babylon and our own Nimrods, even in our consumer choices and how we treat animals — and look, this is a rabbit hole — but this is one of the reasons I went from thinking cheap eggs were good stewardship because we could use the money to look after people or save their souls, to thinking more carefully about what I buy; and it’s part of what’s admirable about those who choose to be vegetarian or vegan in order to not be a Nimrod. I don’t think you have to do that, but it’s a costly decision not to benefit from the Babylons around us. You can’t call people out of Babylon if you’re busy loving life in it.

But we start getting a seed planted here, for the Hebrew reader — because in Shem’s line we get the line of Eber — the Hebrew word for Hebrew (Genesis 10:24). This is the family tree that the rest of the story is going to keep following — all the way to Jesus. We’ve met men of name — the Nephilim — and we’ll see humans trying to make a name for themselves next week in Babel; but Shem’s name is literally the Hebrew word for name; and his family will be the one who represents God’s name in the world. And this is another story where God picks the younger brother, not the older.

This family ends up in the eastern hill country (Genesis 10:30). There’s another movement east; God will call them back from the east when he calls a descendant of this line — Abram — to come and live in the land of Canaan (Genesis 12:1).

But this table of nations wraps up as it begins — reminding us not of the future violence that will tear this family tree apart, but that this is one family spread out through the earth (Genesis 10:32). The story suggests all people share something in common in our humanity; and if we go back far enough in the origin story, it’s that we’re made to live as God’s image in the world; to be fruitful and multiply as we represent Him in the way we rule creation. That’s a stunning view of one’s neighbours, especially one’s enemies — to see one another as siblings. If you’re one of the Hebrew people, whose story this becomes, especially if those neighbours are staring at you along the blade of a sword, making you a slave in Egypt or an exile in Babylon, this is a powerfully different view from the stories you’ll find in those nations ruled by the Nimrods of the world.

As the story of the Bible unfolds, all the nations — even the Hebrews — end up like Nimrod; trying to build kingdoms on violence and bloodshed. And they all end up violently opposed to God — going to war not just with his people, but with him.

So in the story of this line of seed — that becomes the twelve tribes of Israel, and then the two tribes of Judah and Benjamin — the Jews — the story that becomes the Old Testament — these nations pop up over and over again until it all comes to a head. In Ezekiel, God promises to go to war with these nations of the world — nations from our table here, descendants of the sons of Noah — he says, “I am against you” — and names names who come from the table of nations — from the lines of Ham and Japheth — or their descendants. God says he’ll bring all the troops — the warriors — out… from the many nations — a mighty horde of Nimrods who violently oppose God’s people, and then God will destroy these nations (Ezekiel 38:3-6). He will execute judgment the way he did on Egypt — plagues — the many nations will be confronted by God’s holiness, and he’ll make himself known to “these many nations” — the nations of Genesis 10 — the whole world, so they will know he is the Lord (Ezekiel 38:23).

Daniel also picks up the table of nations. After the fall of Babylon and its great Nimrod-like king Nebuchadnezzar (who we’ll see more of next post) comes Persia — a lesser empire. It gets swallowed up in a violent war against the “Kingdom of Javan” (this gets translated as Greece for us in the English), but it’s the same word as in Genesis 10 (Daniel 11:2-3). There a mighty king will be raised up — probably Alexander the Great; a giant Nimrod. Once he dies two Greek empires, based in Egypt to the south, and Syria to the north, fight to the death. This all happened in history and it’s possible that the final written form of Daniel reflects this history. The conflict swallows up the nations of the Table of Nations, as these Nimrods slaughter thousands (Daniel 11:11-13), until the massive Nimrod from the south dies (Daniel 11:45).

But as these nations rage, and these kingdoms rise and fall, God still reigns. Daniel ends with this picture of God’s Kingdom emerging at this time, in this violent world of Nimrods, mighty warriors of the earth, the Kingdom of Heaven will turn up (Daniel 12:1-2). Daniel says when this happens — when God’s Kingdom emerges — the wise will shine not like earthly Nimrods (or even earthling Adams), but like the brightness of the Heavens; shining like stars (Daniel 12:3). He’s already pictured this happening when the Son of Man enters the throne room of Heaven (Daniel 7:13-14).

So, let’s tie up some threads. We’ve got Noah, a new Adam who fails, and whose son fails spectacularly and is cursed to become a servant of servants. From his line, we don’t get servants but Nimrods — anti-Adams — enemies of God’s people. Ultimately, all the lines in the table of nations become like Babylon — like Nimrod — even the Hebrews, which is why they end up in exile, living by the sword and dying by it. We’re waiting for a kingdom of shining heavenly people to emerge, led by a king who won’t take on the grasping pattern of Ham, or be a violent warrior king.

This king builds an empire with power but reveals God’s glory to the world. By the end of Daniel’s timeline — and the Old Testament — all these nations and empires have been united under the biggest Nimrod of all. What Babylon, Persia, and Greece tried to do, Rome does. Rome is an empire that unites these nations through violence. And the cross is where all these threads are tied together.

Jesus — the true Israel — has returned from exile. He’s crossed the Jordan and entered Jerusalem from the east, and entered the temple to cleanse it. At the cross, Jesus is surrounded by a bunch of Nimrods. The armies of all the nations from the table of nations, united under the banner of Rome. Even Israel joins in. These Nimrods put him to death because, like the Nephilim and the serpent, this violence has always been aimed at overthrowing God. And God’s judgment falls on the world, as he also reveals His king and saviour, who ascends to heaven as the Son of Man.

And we have a choice.

We live in a world of Nimrods. In states, and economies, built on violence, grasping, and seedy sex. We turn anything into a fight. Nation against nation. State against state. Culture against culture. Mate against mate. Sibling against sibling. Sport. Politics. Conflicts in community groups, families, even churches. We fight culture wars and jump on bandwagons behind people fighting the good fight. Sometimes we even fight for good things without realizing we’re using the weapons of warfare handed to us by Babylon, so that we become just like our neighbours.

We’ll either pick a Nimrod — or Goliath — a champion — to represent us, or try to be a hero making a name for ourselves in these fights, and that’s just stupid.

We’re called to be people of peace, following the Prince of Peace, not Nimrods.

Look how Paul describes how Jesus fulfills all these threads. We’re not waiting for this kingdom to emerge, for some future battle — the kingdom is emerging, and with it comes a new non-Nimrod pattern for life. Paul says in our relationships we should have the same mindset as Jesus (Philippians 2:5). He’s just unpacked that as having the same love as Jesus, pursuing oneness in his way of life. He says we should do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit — not try to make a name for ourselves — but be humble (Philippians 2:3-4). This is an anti-violent, anti-grasping, anti-Nimrod, anti-Ham, anti-Cain, anti-serpent way of life.

It’s the way Jesus lived when he didn’t consider equality with God something to be grasped. Adam and Eve, Cain, the sons of God, Ham, they all take things to serve themselves, chasing equality with God. Jesus didn’t seize anything for his own advantage, but made himself nothing, became a servant. Ham’s curse was service. Jesus takes on Ham’s curse. He even becomes human (Philippians 2:6-7). God being made in human likeness is an upside-down Genesis 1. Jesus becomes obedient to death on a cross (Philippians 2:8). He lets the beastly Nimrods kill him to expose the evil human heart that even kills God if it meant we could grab more, and at the same time exposing the heart of God that we’re called to share, as his children.

And as he takes on what looks like a curse, descending from the heights of heaven to become the lowest on earth, as he’s given over to violent human empires, God exalts him to the highest place, and he gives him a name — a Shem — above every name, so that at his name not only should every Hebrew knee bow but every knee in heaven and on earth and even under the earth — heavenly and earthly creatures — all the characters we’ve met in Genesis, and every human ever — will bow to him as Lord and King (Philippians 2:10-11). Jesus is the King who brings the kingdom pictured in Daniel — the anti-Nimrod King of the anti-Babylon, and who makes God’s name known in fulfilment of Ezekiel (Philiippians 2:12).

And if we join the kingdom of the anti-Nimrod and take up his call to be people of peace who bow our knee to him, receiving his Spirit to change our hearts and minds — taking on his pattern of love, humility, and service, we’ll be blameless and pure children of God — shining people in a generation of Nimrods. We’ll shine among the other kingdoms like stars in the sky — just as Daniel said would happen when God’s kingdom turned up (Philippians 2:15-16).

As Jesus’ kingdom unfolds in Acts — from Shem’s descendants in Jerusalem and Samaria, to the ends of the earth — we see those scattered in Genesis coming home. Even a descendant of Ham’s son Cush — the father of the Ethiopians — we meet an Ethiopian eunuch (Acts 8:27). He’s reading the Old Testament book of Isaiah, and when this Ethiopian is convinced Jesus is the Messiah, he gets baptised (Acts 8:28-39). This is a picture of the table of nations coming home through living waters. And so are we as we come to faith in Jesus.

Wherever we’re from — in the Bible’s story, we’re humans with the same lifeblood and God’s breath giving us life — and we can become children of God through Jesus’ invitation for all humanity to come back into God’s family tree of life, not by his breath, but with his Spirit dwelling in us.

The radical inclusion of people from all nations marks Christianity as profoundly different from the religious and political vision of Babylon. There’s no more ethnically diverse community in the world, or in history, than the church. And this unity works when we follow Jesus, because he’s a king unlike Nimrod, who builds a kingdom unlike Babylon, or any kingdoms of this world, marked by a pattern of live and love that looks like him.

Don’t be a Nimrod, or line up behind them in any kind of tribalism or culture war that pushes people away from God, be like Jesus. Find your life as a child of God by taking up his pattern of service; not as an expression of curse, but to bless the world.