This is an amended version of a sermon I preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2021. If you’d prefer to listen to this (Spotify link), or watch it on a video, you can do that. It runs for 39 minutes.

I have received more phone calls from strangers this year (2021) asking about the Book of Revelation and the end of the world than about anything else. Revelation is a strange book full of dragons, beasts, and chaos. Its message is coded, and we feel like we have to crack it, and we are tempted to make it about us.

Revelation chapter 13 has this famous picture of a dragon being worshiped because he has given power and authority to a beast who is also worshiped (Revelation 13:4); and we want to know who this beast is and whether it might be around now. Revelation depicts two kingdoms: the inhabitants of the earth who worship this beast and those marked by the Lamb. The Lamb has a book of life (Revelation 13:8). The beast writes a book of death. Whoever refuses to worship the beast is killed by its power (Revelation 13:15).

Whatever the code is in Revelation, whatever it means, it asks readers to consider whom we worship, what kingdom we belong to, whether we worship the dragon and its beastly minions, or the Lamb; Jesus. And the question has consequences. Deadly consequences.

Beastly kingdoms bring death to those who will not jump on board here on earth. The Lamb who was slain on earth offers life in his heavenly book.

As we delve into the Book of Revelation which reveals heavenly reality, opening the curtains between heaven and earth, we are being asked to choose between an earthly kingdom and a heavenly kingdom, a question of life and death.

And this choice has other implications in places where people rule in beastly ways; real-life implications, economic implications, political implications. Because despite what some might say, there is actually no separation between religion and politics. If you take one thing home from this series, it is not that Christianity is political, though it is, it is that all politics is religious, because all politics happens around this fundamental choice between kingdoms.

The beast, or the beauty of the slain lamb, shapes the political and economic behavior of its people. In this famous passage, one that is getting a run in the media at the moment, the beast uses a mark, an imprint—the word here is often used for images stamped on coins (Revelation 13:16-17). In this vision, if you do not have that mark, you do not participate in the economy, you do not benefit from the kingdom of the beast.

And the mark is the number or name of the beast, and we get this famous number, 666 (Revelation 13:18). Now, we will dig into this more in a few weeks’ time, but the key to understanding all this apocalyptic stuff is to read it carefully. And John, who is writing, says discerning what he is talking about requires wisdom (Revelation 13:18), and that while we might think this is going to be supernatural and demonic, it is actually natural and demonic. It is about a person, a man beast, who is on earth doing the will of the dragon.

So it is very unlikely that COVID vaccines or credit cards or all sorts of things that people have identified with this passage over the years are the fulfillment of the events depicted in Revelation.

Revelation is an apocalyptic text that stands in a tradition — an Old Testament tradition — that frames the world this way, from the perspective of heaven, to invite us to consider how we live, what kingdom we belong to, who we are and will be as people, as we choose what to worship.

It is a book that is the fitting conclusion of the story of the Bible because John’s vision is incredibly grounded in the image and story of the Bible. This choice between beauty and beast goes right back to the beginning.

Right back to the serpent — Satan — a beastly wild animal. People were meant to rule over wild animals as God’s image bearers, but the serpent slides into their direct messages (Genesis 3:1).

Adam and Eve were clothed in the glory of God, naked and unashamed, reflecting his goodness and love, and then the serpent claws them away from God. They become people ruled by a wild animal.

And we get a hint that the fall is a turn toward beastliness as Adam and Eve are clothed in animal skins. They become like the animals (Revelation 3:21).

But now, humans are caught up in a fight with the wild things. But there is hope. There will be a fruitful line, a line of seed, offspring, who will be opposed to beastliness and crush the serpent (Genesis 3:15).

There will be a battle that will determine if people are human as God created us to be, beautiful reflections of his image who rule over the wild things, or humans ruled by the animals, beastly humans.

We see this beastliness take hold in the next story, the story of Cain and Abel.

Abel has mastery over the animals. He cares for the flocks. But Cain is at risk of being mastered by the animals, becoming beastly.

God warns him, “Sin is crouching at the door,” like a beast waiting to pounce. It desires to have him. He must rule over it, not be ruled by it (Genesis 4:6-7).

But instead, Abel’s blood soaks into the ground, and Cain is exiled to live like the beast-man he has become.

In the story, his descendants go out and build cities, full of technology, tools, and instruments, but they are cities of death, where within a handful of generations, this fellow Lamech is boasting about bringing death and destruction to his enemies.

And that is the story of human empires produced outside the line of seed that will lead to the Lamb. Genesis has these stories of humans and empires who become beastly as sin takes hold. They are cities of order and technology and even art and culture. The trains would have run on time. But they are cities like Babel, Babylon, disconnected from God’s presence. Beastly kingdoms ruled with violence.

But throughout the story, there are little glimpses of both the hope and the fight against beastliness.

One example is David, the shepherd king who tends a flock, who rules over the wild animals, lions, and bears who come to kill his sheep (1 Samuel 17:36).

That is interesting, right?

But here is something even more fun, courtesy of the Bible Project.

Goliath, the giant, is presented not just as a beast but as a giant serpent.

Every time the narrative mentions his bronze armor, scaly bronze armor, it is a serpent pun. The Hebrew word for bronze uses the same letters as the word for serpent. They are related to the same root. He is bronze and scaly. He is snakey. He is beastly. He uses human power and strength, weapons, to mock God and his people. He comes with sword and javelin and snake armor (1 Samuel 17:4-6), while David comes against him in the name of the Lord.

And we know the story.

David defeats this beast-man, and his head is crushed (1 Samuel 17:41). David becomes king. He launches a “city of peace.” He uses his strength to crush beastly kingdoms, like a shepherd. The catch is that in his own temptation, his grasping, his use of the sword, especially with Bathsheba and Uriah, David grasps and kills those in his care. He is rebuked for being a predator rather than a shepherd, and he is told the sword will not leave his household. He got too close to beasts and became beastly.

The closest parallel to Revelation and the book where the beast theme really gets unpacked is the Book of Daniel. There, before the vision we read, there is a story where someone is dressed like an animal as a picture of beastliness.

The Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, he has a dream, and Daniel interprets it. He says Nebuchadnezzar will go live with the wild animals until he worships God’s authority as the Most High. He becomes like a cartoon beast, an apocalyptic figure, an ox, an eagle, with hair like feathers and claws like a bird (Daniel 4:20-33). This is a picture that portrays Babylon and its power in beastly terms. If Israel in exile is tempted by the beauty of Babylon, here is a view of that beauty from a heavenly perspective revealing its ugliness.

Then Daniel has this vision of four great beasts (Daniel 7:2). And, like with Revelation, we are tempted to try to see these four great beasts as kingdoms still to come, pictures of the end of the world. We might look at ISIS or America or all sorts of modern kingdoms and try to make the hat fit.

But there is a more immediate fulfillment for this apocalyptic vision because this apocalyptic genre is a way that people can speak about present moments from a heavenly perspective.

Daniel’s vision is explained straight away. The four beasts are actually four kings who will arise from the earth (Daniel 7:17), and they might look powerful and victorious as they destroy or dominate God’s people, these beastly regimes, but actually, God is going to win, and he is going to give a kingdom to his people forever.

And these empires around Israel were overtly and deliberately beastly. Their gods were presented as animals, serpents, dragons, weird hybrid animals, like this Babylonian picture. Their stories were violent and bloody. The kings of these nations were seen as supported by beastly gods, who triumphed, tooth and claw, over other beastly gods.

Babylon’s creation story involved the Battle-God Marduk creating the world from the dead body of the serpent God Tiamat — who was also a symbol of the chaotic waters. Marduk then built Babylon as the seat of the gods on the earth; the bridge between heaven and earth. There is this idea that goodness and peace and cities of order and beauty are built out of death and destruction and violence.

Daniel’s vision — and in the narrative that goes with it in the book of Daniel — pictures a beastly empire with a beastly king. When the king of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar, is sent into beastly exile as an animal it’s a picture of Babylon’s beastliness. When the Medes take over from Nebuchadnezzar’s son in the story of Daniel, Darius the Mede is the beastly ruler who throws Daniel to the beastly lions because he will not worship him and his gods. Then a third kingdom, the Persians take over, with Cyrus mentioned just before Daniel’s vision is described in the book; a vision is set back under Babylonian rule; back before the events of chapter five. Daniel’s vision features beast… after beast… after beast… until Daniel pictures a fourth beast; a super-power who will come in and do horrible things to God’s people (Daniel 7:21-27). And it is very likely that this superpower he pictures is Greece, and that it is pointing Israel to Antiochus Epiphanes, a Greek king who marched on Jerusalem, setting up a statue of himself on the altar in the rebuilt temple; a moment the Maccabees, a Jewish text, calls the abomination that causes desolation.

And the thing all these regimes have in common — according to Daniel — these regimes opposed to God is that they are beastly, and though they look victorious and powerful and majestic from an earthly perspective, they do not win. They swallow each other, and, ultimately, God swallows them up. These beasts represent kingdoms; earthly kingdoms that devour and trample and crush; kingdoms marked by kings who will lead mighty armies. These beastly kingdoms are violent. They wage war against each other, and they wage war against God’s holy people. These are dominion systems pounce on and devour the weak.

And these beastly kings will set themselves up in opposition to Israel’s God. They are earthly pictures of cosmic rebellion against God’s rule. And the only hope for God’s people amidst these beastly empires is for God — the Ancient of Days — the Most High — to step in and put things right in the heavens and on earth. So Daniel has this vision of the heavenly court sitting and ruling on the actions of this beastly regime, and the Most High taking the reins both in heaven and in the kingdoms under heaven, and launching an everlasting kingdom where all rulers will worship him (Daniel 7:26-27). We will see Revelation picking up lots of this language.

In Daniel, the beasts get slain at this moment when God is revealed as the rightful God of the nations (Daniel 7:11), and his king, the Son of Man is enthroned in heaven (Daniel 7:13), and in Revelation chapter one, in John’s vision of Jesus in the heavenly throne room, this has already happened. In Daniel’s vision the total victory over all other empires in the heavens and the earth is secured as the Son of Man is given an eternal kingdom covering all nations that will never be destroyed. He is worshipped in the place of the beast (Daniel 7:14).

So as we approach Revelation and its picture of beastly regimes, there is a whole lot of this symbolism that is being drawn from the story of the Bible. Beastly regimes are those empires — military and economic and political systems — religious systems — that set themselves up in opposition to God’s people as people are pulled away from glory into beastliness by the serpent.

And as we read Revelation we have to remember that while we might want to make it about us, here and now, it is first a real letter to real churches facing their own beastly regime (Revelation 1:4). One that looks like it has crushed the serpent crusher. There is a new violent and beastly kingdom serving the agenda of the dragon, Satan, but whose false beauty, the “peace of Rome,” is secured by violence, and the worldly power and beauty of Rome is tempting people to worship its gods (and emperors).

This is the regime responsible for executing Jesus who will now set about not just persecuting Christians at various times — but worse, even — it will set about asking to be worshipped; proclaiming itself and its kings as the good economy, the good empire, with the mightiest army and the best gods. Rome is not all stick, there is plenty of carrot; plenty of temptations luring people to beastliness.

It looks impressive and wealthy and powerful; it offers pleasure and peace and prosperity. That is the temptation for Christians; it is not just about martyrdom, but about the same choice that faced Israel in Babylon — do they worship God or the beast?

John is writing to people with an immediate message, presenting an important choice. And that choice will end up being life and death, because beastly empires do not tolerate opposition — they use the sword to build their kingdoms.

The Roman empire will require worship. Revelation is probably written around the time of Nero — I think probably just after his death, but it could be any time in the first century. By the end of the first century, Rome is ruled by the emperor Trajan. One of his governors, Pliny writes a letter to Trajan asking what to do with these pesky Christians springing up in his province, Bythinia — it is a region in modern day Turkey — right on the border of the province of Asia (where the letter is addressed).

Pliny says when people are accused of being Christians he interrogates them, when they confess he interrogates them again with the promise of punishment, and those who will not recant he executes. That is beastly, right? But it is just a matter of course — it is a procedure. It is like he is trying to give these Christians an easy way out too. All they have to do is worship the beast. He says:

“…in the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have followed the following procedure: I interrogated them as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed.”

He says the path out of execution is conforming to the Roman gods — worshipping their gods, including the image of the beast-king:

“Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods…“

And Pliny writes back…

”you have observed proper procedure”…

This is the context Revelation is written to; an empire that demands worship and lures Christians away from faithfulness with bright lights, and the ‘peace of Rome’ — a peace won through violence. And so the invitation is there: Choose a kingdom; Choose a king.

Worship the image of the beast, carry his mark (Revelation 13:15); and know that you are really worshipping Satan — the dragon (Revelation 13:4) — and so will become beastly… Or worship God, and be marked by the Lamb.

The beauty or the beast…

It is interesting to think back to that moment when the Pharisees test Jesus with the coins at this point… the Pharisees, who will end up teaming up with the beast to kill the Lamb. They come asking about paying taxes to Caesar (Mark 13:16-17), bringing little metal disks marked with the beast’s image — the face of the empire — little marks that allow people to buy and sell. And they ask “should we pay tax to Caesar” — should we participate in this empire?

Jesus’ answer has often been interpreted as saying that we should participate in this empire — pay these taxes — take part in the politics of the day because Caesar has the right to tax us, and there are all sorts of reasons — like Romans 13 — to think that is true. But there is more to his answer. When you ask yourself “where is God’s image”; how do we then give our whole selves to God?

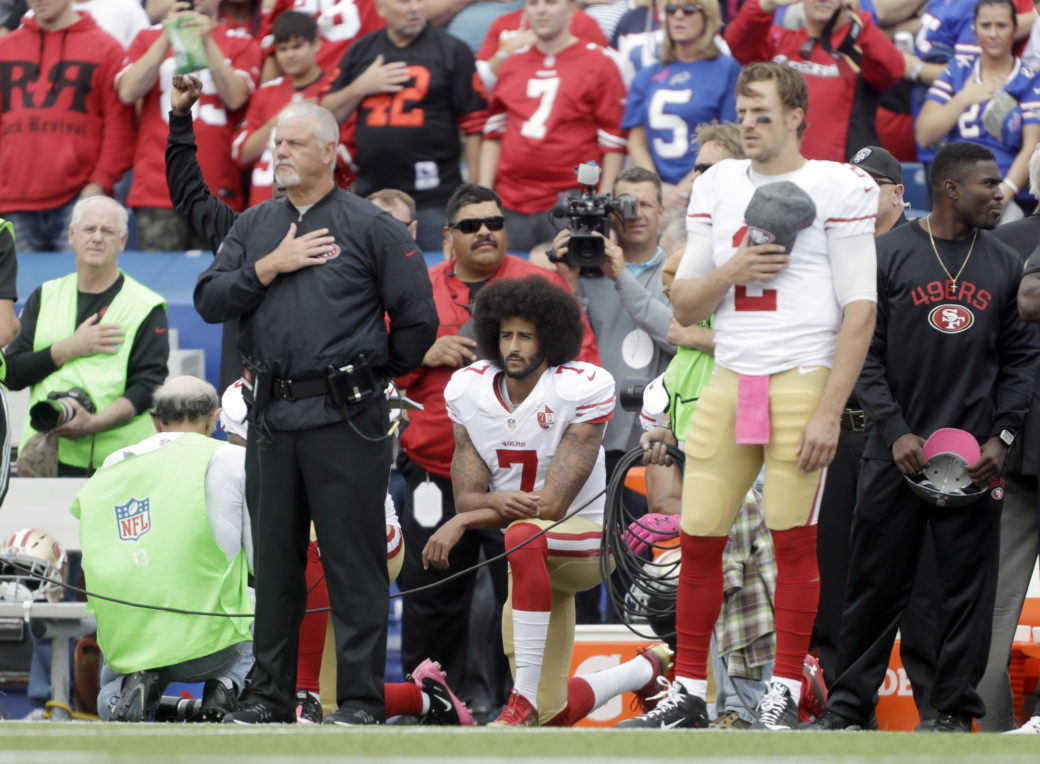

Our participation in human empires — as people who belong to God — stops when these empires ask us to worship. We see that in Daniel, we see that in Jesus, and we will see that in Revelation.

Jesus calls us to worship God, with your whole life; to give God what is God’s — and be marked by Him, not to be swept up in a beastly empire.

We live with our own beastly regimes that call us to worship — that invite us to become serpent-like.

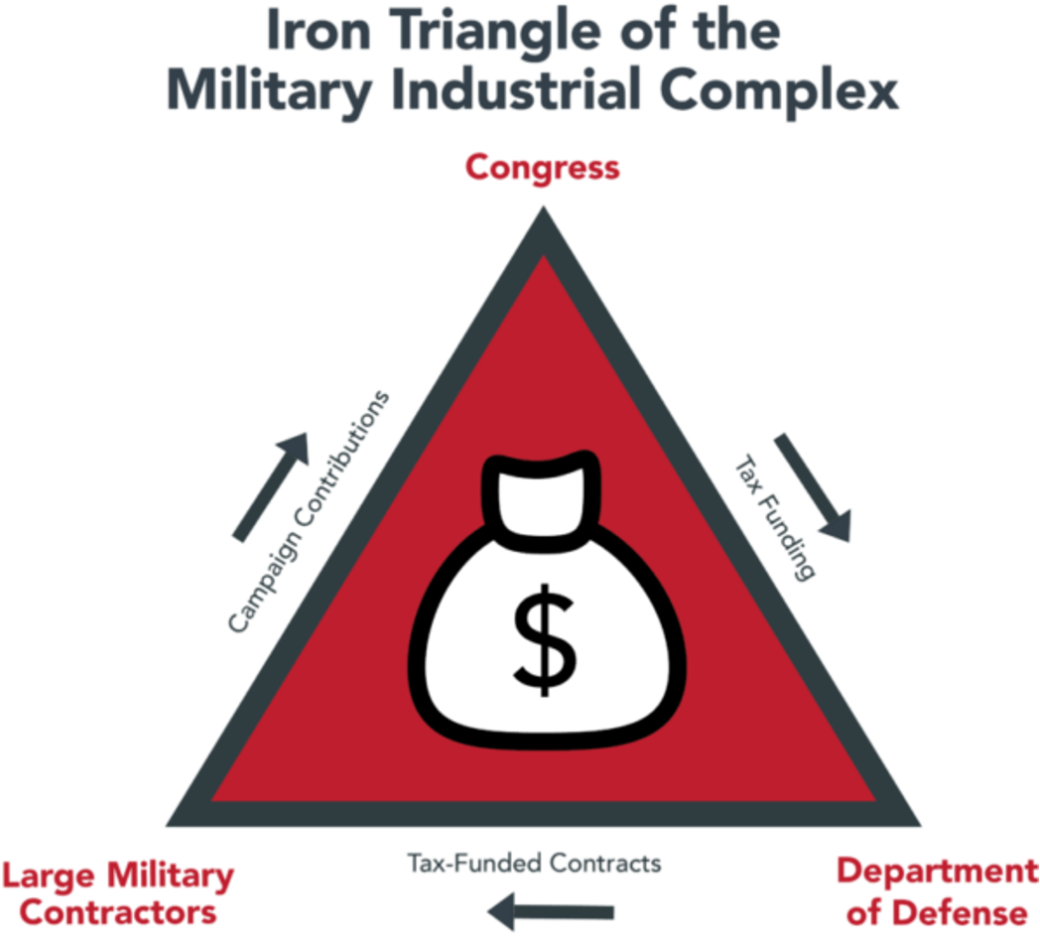

The former US President, Dwight Eisenhower, described a “military industrial complex” at the heart of the U.S empire. It is the heart of the Western world and the peace and prosperity we enjoy — a vicious cycle where the economy and the military and the politic systems are deeply enmeshed — producing an empire built on the capacity to be mighty and violent.

Now. We might feel a step removed from the U.S as a ‘middle power’ here in Australia, but the news recently of an AUKUS alliance does not let us bury our heads in the sand. We are marching in lockstep with this empire, and this approach to the economy.

And we do it thinking we are the good guys, just like the Romans and the Babylonians, bringing peace because we have a bigger sword. And this is not to say that governments should not wield, or buy, swords — the Bible literally describes them as a sword. Beastly governments are the ones that call for our worship, and pull us away from life shaped by the crucified Lamb, and think that salvation and redemption and peace lies in the way of the sword, rather than the beautiful way of the cross.

There is a Pentecostal theologian named Walter Wink who describes the modern world and its military industrial complex as a domination system — another way of talking about this is to label it as it is… beastly. He says The Myth of Redemptive Violence is the real myth shaping the modern world. It, and not Judaism or Christianity or Islam, is the dominant religion in our society today.

He sees this myth as essentially Babylonian — tracing our stories about heroes using violence to secure peace back to Babylon’s creation story, and to the Roman idea of peace. This myth is everywhere from Marvel movies to the stories we tell ourselves about peacekeeping as we send armies into places like Afghanistan. Wink says the Babylonian story has clear implications, that ultimately produce an ethic for kingdoms who follow the story:

“The implications are clear: “human beings are created from the blood of a murdered god. Our very origin is violence. Killing is in our genes.“

That we cannot imagine a world without armies — the sword — or solutions without domination of the will of the ‘good’ over the evil, secured through violence, demonstrates this. This myth — the idea that violence can be redemptive — that the sword wielded by government can save — is how beastly powers dupe us into complying with the system. Wink says:

“By making violence pleasurable, fascinating, and entertaining, the powers are able to delude people into compliance with a system that is cheating them of their very lives.”

This myth takes hold of our imaginations … it shapes our politics and our relationships and gets us participating in the machine — because the benefit of being complicit is that our security and power gets us cheap stuff from those we exploit, but this is how we lose our souls and become beastly.

The thing about democracy, too, is that we kind of all end up as kings and queens of our own little empires. We all have the capacity to be beastly as we choose what to worship — especially when that choice happens in a violent system shaped by this mythology, and in a global capitalist system where greed is good and we are disconnected from the production of the things we buy and enjoy.

I read this story this week about the environmental and economic destruction brought about by our need for cobalt — did you know you need cobalt? It is a vital part of the batteries in all our smart things — and this destruction is not in your backyard, but it is literally in the backyards of people in the Congo, whose lives are being devoured by our consumer behaviour. Or Lithium; the other vital component in batteries — the ones that power smartphones and electric cars, where the rapacious mining for these commodities destroys the environment in countries like Chile.

This sort of thing is much more the mark of beastliness than a vaccination. Maybe it will get harder and harder to buy stuff or participate in the modern economy without a smartphone in your pocket. But it is easier not to think about that, and not to think about how our military might — or China’s in the case of cobalt mining — or the economic power of the first world might perpetuate this issue and guarantee the supply chains and the exploitation by preventing revolution.

Maybe we think it is better to be in the empire, worshipping its idols than opposing it and being thrown to lions. Maybe we think we can have a foot in both camps?

But here is the thing.

You have to choose.

The beast, or the beauty.

You have to choose your kingdom and your king.

Choose who to worship and serve.

And doing that has to shape your politics and your economics and your approach to the sword… to power and violence. Because actually your politics and economics show what you have really chosen…

Jesus has created a kingdom — not a beastly kingdom but a priestly kingdom… Not a kingdom of violent dominion but a kingdom of servants of God, for his glory, secured by his blood.

He is the serpent-crushing son of man — the King of Kings — who brings the beautiful heavenly kingdom Daniel saw in his vision, and that John describes here… but he does not do it through violence… he does not crush the serpent with a sword… but with his blood. His story is not one of redemptive violence but redemptive sacrifice, where even if he slays the dragon, he does this through his death, absorbing the dragon’s blows. He is not just the shepherd king, but the lamb slain; he turns the myth of redemptive violence in on itself. He does not live by the sword.

His kingdom, as we will see through Revelation, looks very different to the grasping and devouring kingdoms of this world.

John grounds his vision in the victory of Jesus that has already happened; at the cross, and in the resurrection and ascension of Jesus, the son of God and son of man, as king of heaven and earth.

The story of the Bible is the story of the victory of God over sin, and death, and Satan — and ultimately the beastly kingdoms and humans who follow the way of the serpent into beastliness… through the sacrificial love of his chosen king… the serpent crushing seed… the lamb slain before the creation of the world.

And now we have to choose. And you really only have two choices — Satan, who loses, or Jesus, who wins. The beast, or the beauty.