“If you don’t defend yourself against these devils and demons, you’re a coward.”

That’s a line from a video the shooters in an act of domestic terrorism posted (since deleted) during their meticulously planned ambush of police officers attending their rural property. In a press conference summarising police investigations of the attack, Queensland Police Deputy Commissioner Tracy Linford described the fortifications of the property and the conclusion police had reached that the shooters had been waiting for this moment for some time.

In this same press conference, Deputy Commissioner Linford revealed that the investigation had concluded that this was an act of Christian terrorism; that the shooters were motivated by a particular religious belief — a Christian eschatology (a view of the ‘end times’ called pre-millenialism)— where they truly believed the officers from the police service visiting their homes were demons.

“From all the material we can see different statements made by the Train family members; whether that be in texts, whether that be in emails, whether that be in diary entries, comments on calendars, we can see they do see the police as monsters and demons. We don’t believe this attack was random or spontaneous. It was an attack directed at police.”

Now. Not all people who hold to a pre-millenial eschatology will believe that police are demons, or that violence is the way to achieve the return of Jesus for his thousand year reign. That goes without saying. Because we can simply observe that there are lots of people who hold this eschatology (I don’t) who do not build bunkers and trenches and escape hatches in their properties or shoot police officers in cold blood.

I think it’s also important — in the first few hundred words of this post — to point out the obvious. The Queensland Police Service is likely to be taking this investigation quite personally; they lost two members of their community, while others were injured; if there’s a widespread movement that sees police as demons to be shot it’s in their interest (and the interest of the community at large) to get to the bottom of things; and to articulate as clearly as they can the motives of the shooters. If you were going to comment on this story, and their investigation, I think it would be pretty important not to be presenting the police as anti-Christian demonic type pawns of an evil empire. I think it would be important to understand their motives in releasing, in as close as possible to the words used by the attackers, the motives behind their attack.

It would also be, I think, wise, to acknowledge our limited access to the material examined in the police investigation when assessing the accuracy of the claims. In the media release accompanying the press conference, Deputy Commissioner Linford said “specialist teams have analysed an extensive amount of evidential material including diaries, books and notes located at the scene, phone messages, emails, social media posts, witness statements and body-worn camera footage.” That’s a lot of material we are not privy to regarding the frame of mind of the attackers; and a lot to summarise in a single sentence digestible by the public.

The result of this investigation is the conclusion contained in the media release that:

We now know that the offenders executed a religiously motivated terrorist attack.

“They were motivated by a Christian extremist ideology and subscribed to the broad Christian fundamentalist belief system known as Pre-Millennialism.”

Now. There have been some mistakes made in accurately describing an eschatological system that can sound crazy even to theologically informed Christians who hold to different eschatologies; there is no singular expression of pre-millenial thought. And, rather than saying “hey, the Police are in ongoing danger from Christian extremists,” the release minimises that fear — it concludes “there has been no evidence to suggest anyone else was involved in executing the attack in Australia or that there is any ongoing specific threat.“

If I was a serving officer in the Queensland Police Service, or a member of the Australian public, I think my fears would be put to rest knowing that this was an act of Christian terrorism from a very fringe expression (fundamentalist) of a reasonably fringe eschatology (premillenialist).

If I were a Christian in Australia (which I am) I’d be wanting to reassure others not only that this was not an act consistent with the character of Jesus or our expectations of his return (which it isn’t), but also that the police are not demons but are in fact the God-appointed agents of the government; those who ‘wield the sword’ to uphold justice. There’s a thing responsible (white) parents do (in Australia) where they teach their kids that police are friendly and approachable and that you should smile and wave when you see them, that you shouldn’t feel anxious and run. Our Police Service isn’t perfect; there’ve been chapters of corruption, and systemic problems around women, First Nations people, and sexual minorities that’ve been subject to investigations and inquiries; I’m not suggesting we be naive. The Police Service, like any human institution, is made up of humans whose natures are a mix of the image of God, sin, idolatry, and perhaps even the influence of the powers and principalities — but it is not demonic, and human police officers are not demons; they are our neighbours, families, and friends bound by oath to protect and serve us. The Oath that Queensland Police swear as they are admitted to the service says:

“‘I, ___, swear by almighty God that I will well and truly serve our Sovereign Lady Queen Elizabeth the Second and Her Heirs and Successors according to law in the office of constable or in such other capacity as I may be hereafter appointed, promoted, or may be reduced, without favour or affection, malice or ill-will, from this date and until I am legally discharged; that I will cause Her Majesty’s peace to be kept and preserved; that I will prevent to the best of my power all offences against the same; and that while I shall continue to be a member of the Queensland Police Service I will to the best of my skill and knowledge discharge all the duties legally imposed upon me faithfully and according to law. So help me God.’.

Were I a Christian commentator I think I would be expressing grief, as a fellow human, about the lives of those officers killed in the line of duty; upholding that oath (or the alternative affirmation provided by the legislation). I certainly wouldn’t be centering my own feeling of being a victim of a culture war because the police media statement was not as precise about the motives of the shooters as I’d have liked.

And yet.

We live in strange times.

I’m going to try to tread quite carefully here. Because the last time I suggested that commentators from what I would call the “Christian hard right” were using rhetoric that might produce violence, an editor of one of those prominent publications threatened to sue me, and Eternity News, while also writing to my denomination accusing me of bullying. In that piece — once deleted from both here and Eternity (that I’m going to restore on this page), I suggested that the irresponsible use of violent metaphors and language in a ‘culture war’ would legitimise violent actions from culture warriors who believed they were acting in some sort of holy war.

I suggested we should focus our energies on loving our enemies; and the way of the cross. In a subsequent conversation with one of the blokes I named in my piece I made the case that Jesus’ call to “take up our cross” gives us a paradigm for bearing faithful witness; and that when Revelation (the book of the Bible that premillenial eschatology comes from) describes Christian engagement in the public square as witnesses; those witnesses are put to death by the rulers and powers — they don’t go in with their swords drawn; but that this vindicates our testimony to the king whose kingdom is not of this world, who triumphs through death and resurrection. Our call is to martyrdom; martyrdom is not necessarily death and suffering at the hands of a violent state (should the God-appointed sword unjustly turn against us); martyrdom literally means “witness” — the Greek word for witness is martyr.

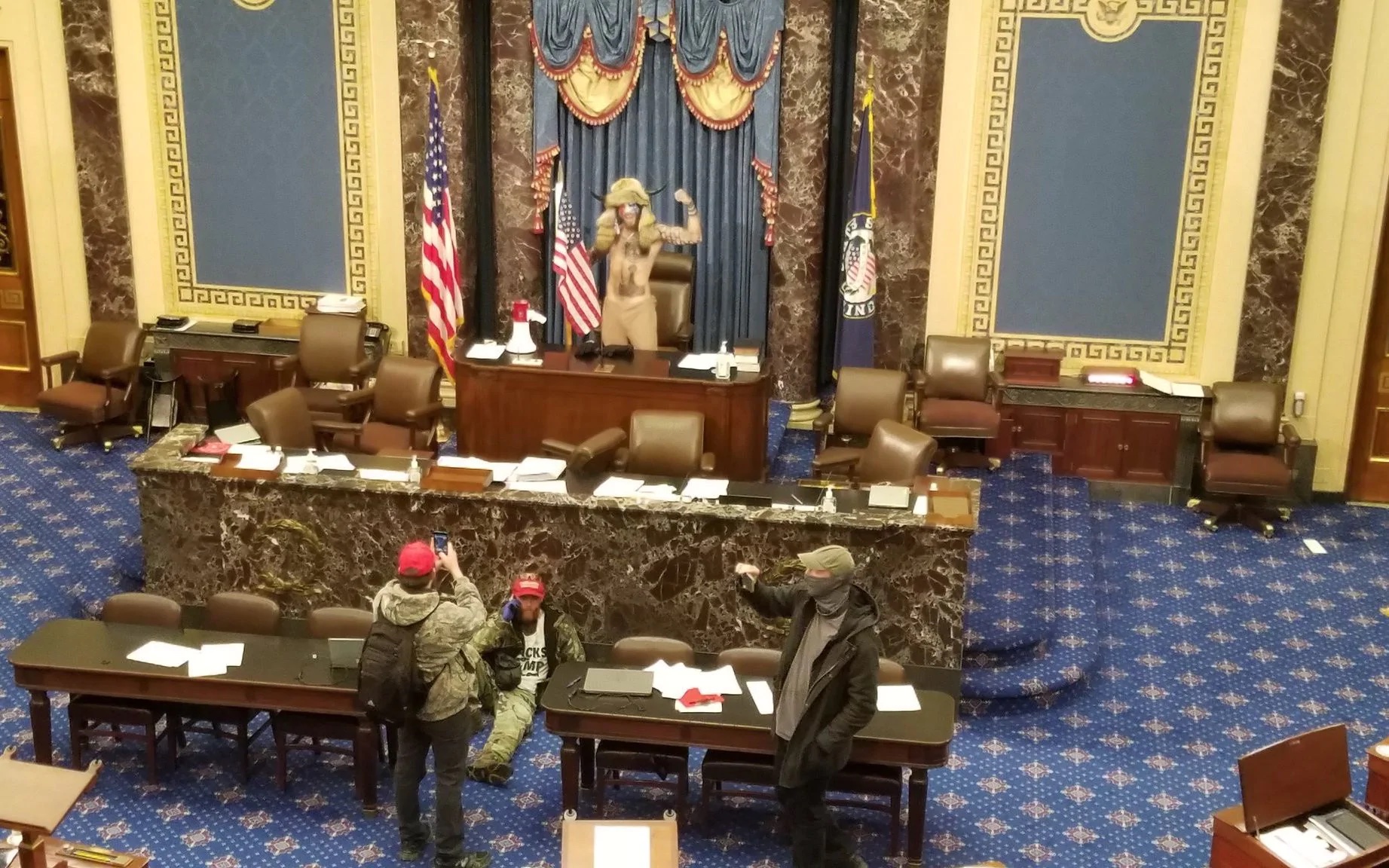

I suggested that should our rhetoric continue to fuel a culture war, and continue to legitimise violence, that we would see versions of the Capitol Hill Riots — where armed protestors stormed a government building carrying firearms and other weapons; oh, and Christian placards.

Evidently, not all people who read a website like the Caldron Pool are motivated to commit violent acts by the culture war language, just as not all premillenialists do. That’s important to acknowledge; and it is also important to acknowledge the horror the editor of the Caldron Pool felt when I suggested that his writing, and his platform, would legitimise violence. I want to be clear that this is not his intent as a communicator; but I also want to clearly say that this is an implication of the language that he, and others, use that becomes part of what you might call ‘the social imaginary’ of the sort of person who does see the police as a demonic expression of a satanic state, and so understands their duty to be to take up the sword (or the firearm).

I know that there’ll be those who think that I am not the right person to say this; that I am a bad faith critic of the Caldron Pool (and others). I did, afterall, register caldronpool.com.au at one point and call them names. But consider, for a moment, that I might be a canary in the coal mine — just the first hyper-sensitive reader to chirp up and say: “hey. This is a problem.” It’s very possible that this is motivated by antipathy towards Ben Davis, the Caldron Pool editor, on the basis of interactions I had with him in the cesspit that was a Facebook group known as the Unofficial Presbyterian. But I’d love to urge Ben — and others — to use this moment to reconsider the language they use — even when talking about this very story. Because we communicators do bear a certain responsibility for the worlds and possibilities enabled by our words. This isn’t to say that the Train family wasn’t fully responsible for its actions — but, I’d certainly want my conscience to be free from even having to consider that my writing was amongst the material the police had to encounter when investigating why members of their own community were heinously gunned down while upholding their oath — one that concludes with a prayer, “so help me God”…

You’d hope that someone so sensitive to criticism that his writing might enable violence would do two things when violence linked to Christian extremism (of a hard right variety) occurred. You’d hope that such a person would immediately distance Christianity from the attack; robbing such actions of any legitimacy connected to their words and platform, and perhaps you’d hope for a degree of self-reflection and a commitment to not further demonising the institution (or the government). I’d personally hope that this sort of event be one where we don’t play the victim, or use the events as grist for the culture war mill.

Ben Davis (editor) and his site Caldron Pool have managed one of three; joining other prominent commentators from the hard right accusing the police service of being part of a government vendetta against Christians. It’s clear that none of the commentators I’m about to quote believe that Christianity legitimises this sort of violence; or that it can be at all Christian. The issue is that the police have carried out an investigation that concluded these three individuals — Nathaniel, Gareth, and Stacey Train say they were motivated by a particular view of the world, its end, and the role the police play in a cosmic conflict (as demons). The police are working with the words of the shooters, and may have been clumsy in their presentation of the facts when it comes to what premillenialism is; one statement said it was a 1,000 day reign of Jesus, when it is years — but, the way numbers should be interpreted in the Bible is hotly debated, a day is a thousand years and a thousand years is a day, so maybe give them a break, and most Christians couldn’t articulate their neighbour’s version of premillenialism and its political implications anyway.

In Ben Davis’ article, the first article of four published by Caldron Pool about the media conference and the findings in the investigation, he said:

“What the Deputy Police Commissioner fails to understand is that Christianity (and Premillennialism) is not responsible for any injustice orchestrated by professing Christians, because every injustice is carried out contrary to Christianity.”

This sounds a lot like a no True Scotsman fallacy; and, while I’m reasonably hopeful that the Trains weren’t members of the invisible church; those who are marked by God as his through the gift of his Spirit — their words (and reputation before the event) suggest that they were professing Christians and that their actions were a result of their beliefs about what Christianity is; this, then, is an in house matter for us Christians — we have a responsibility to rightly teach and discern God’s word. I would suggest the police — as an expression of “the sword” (those appointed by God to wield temporal power) — aren’t meant to figure out who is, and isn’t, legitimately a Christian (part of the invisible church), but to deal with the visible.

Ben says some good words to make it clear this attack was reprehensible.

“So, let’s be absolutely clear: All horrors and injustices bear witness, not to the cruelty of Christianity, but to the cruelty of humanity when they deviate from Jesus’ command to love even your enemies and do good to those who hate you.”

But then Ben pivots — he starts to look elsewhere for someone to blame — or something to blame — anybody but the broader Christian church, and its splinter communities, who were part of forming the Train’s imaginations.

“Christian ideology” can’t lead to terrorism until it deviates from Christianity. If anyone is to give an account for violent extremism, it’s not Christianity which demands strict observance of Christian instruction, but those who dismissed the Bible and attempt to operate outside the bounds and authority of God’s inspired Word.”

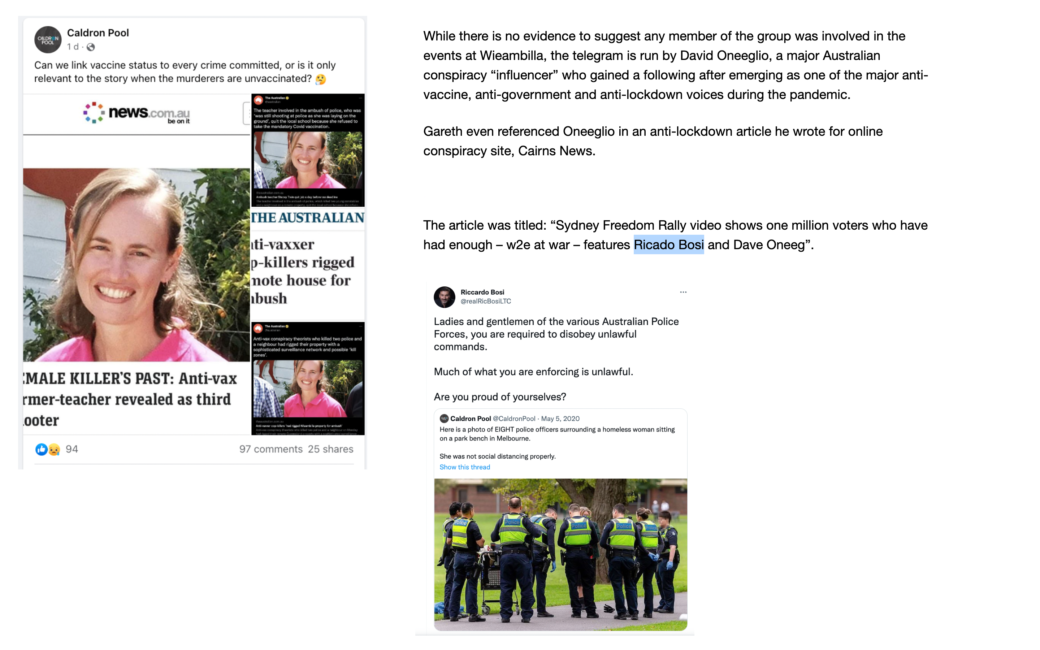

Before I go on to some other commentators, there are some images I’d like to share to help paint a picture. The first is a post from Caldron Pool’s Facebook page when it seemed the shooting was motivated by vaccine mandates. The second is a highlighted quote, in one of the early news articles about the attack, quoting something Gareth Train had posted on a conspiracy site, and the third is a hard right figure mentioned by Train retweeting a Caldron Pool photo critical of Police (and government) for what you might summarise as “operating outside the bounds and authority” established for government in God’s inspired word (at least in the opinion of Caldron Pool). Now. I want to be clear — I don’t think Caldron Pool is responsible for the shooting — but I do think their language, articles, and culture war narrative fuel a vision of the world that is part of a potential motivation for Christian violence (albeit a crazy one).

“We can see they do see the police as monsters and demons” — Deputy Commissioner Linford.

“If you don’t defend yourself against these devils and demons, you’re a coward.” — The Train family.

There is no moment in the Ben Davis article, or subsequent Caldron Pool articles, that attempts to read the Police media statement charitably, or see the conclusions of their investigation as a legitimate summary of the evidence. Instead, subsequent articles serve to paint the finding as part of a deeper anti-Christian agenda in the corridors of power.

The next Caldron Pool article, chronologically, is by Tom Foord — the local Brisbane pastor who made a hate video about me and other namby pamby “take up your cross” Christians who won’t jump in boots and all to the culture war. Foord, in his piercing cultural analysis, says:

“If you’re surprised that the Aussie government would risk alienating all Premillennialists in their broad stroke of idiocy, (which includes many Baptists, most Pentecostals, and plenty of non-denominationals), you haven’t been paying attention. They don’t mind calling any historic Christian doctrine “conspiratorial”.

Let’s be clear — this is reducing an investigation digging into the expressed motivations of three cop killers into a “broad stroke of idiocy” while expanding the Deputy Commissioner of the police into a narrative that includes “the Aussie government” — it’s a move that paints a classic culture war “us v them” narrative positioning the state against the church, and painting the state as exactly the sort of institution a pre-millenialist fundamentalist might begin to see as demonic. And his last line in this piece of “thought leadership” — and remember this is still a story about a situation where four police officers were gunned down, where two of them, and a member of the public, died — “Who cares what the coppers think, anyway.”

Let me repeat that so it doesn’t get lost in that big block of text:

“Who cares what the coppers think, anyway.”

“Who cares what the coppers think, anyway.”

“Who cares what the coppers think, anyway.”

This is from a man who presumes to be a teacher of God’s people — and also to criticise other pastors for daring to suggest that the commands and example of Jesus ought to shape the way we present our faith and engage in politics.

But it’s also from a platform that has spent much of the last two years de-legitimising government authority and painting them in spiritual warfare terms overlaid with culture war rhetoric.

“We can see they do see the police as monsters and demons” — Deputy Commissioner Linford.

“If you don’t defend yourself against these devils and demons, you’re a coward.” — The Train family.

The third article on Caldron Pool’s from a bloke named Bill Muehlenberg.

He opens:

“They Really Are Sinking to a New Low in Their Anti-christian Bigotry

A strange title, admittedly, at least to non-Australians. But those who live here probably know what I am referring to. It has to do with some wild, reckless and defamatory comments made by some officials in the Queensland Police Department, and the mainstream media.”

We’ve shifted now so that we Christians are the victims of a slur by the police as part of some agenda; rather than the police being victims of an attack motivated by a bastardised Christianity. It’s almost like they deserved it; it’s almost DARVO — a classic abuser move where you flip the victim and perpetrator; only, like the others, Bill does not believe violence is Christian — it’s not clear that he doesn’t think the state and its officers (who swear an oath to serve the people, of our western nation, with God’s help) are demons.

In fact. He says:

“Whenever you have the police and the media wading into the deep waters of theology, you know we are going to have a real hatchet job – and a confused and malevolent one at that.”

Just to be clear the word “malevolent,” it means evil.

And, to complete the Caldron Pool two step (or three step) to turn this police shooting into a culture war call to arms, Bill concludes:

“And just wait for more attempts to classify Christianity as a whole as a terror group that needs to be closely monitored if not shut down altogether. That is in fact the end game for many of these Christophobes.”

The Government is out to get us folks; and the police are on the front lines because they’re Christophobes who might call us terrorists.

“We can see they do see the police as monsters and demons” — Deputy Commissioner Linford.

“If you don’t defend yourself against these devils and demons, you’re a coward.” — The Train family.

Where on earth did they get these ideas? The shooters?

This is dangerous nonsense. There is a spiritual war — theologically speaking — it’s the war between the way of Jesus and the way of the world; the self-denying way of life-sacrificing love for one’s enemies — even if they are out to get us, and those who would take up the weapons of this world — whether physical weapons or tools of power and manipulation, and culture warriors are not faithful witnesses to Christ — those prepared to lose everyting; even their lives, while turning the other cheek; they are pugilistic and demonic voices inside the church. The sorts of voices that lead others to violent rejection of the way of Jesus. I don’t believe Ben, Bill, or Tom are at all interested in leading people that way; I hope they are interested in leading people to Jesus — and so I’m prayerfully asking them — and others to stop. To think about the impact of their words — to consider the way they are framing events like this in their own minds and the minds of others.

Dave Pellowe, another who I named in my deleted Eternity post, runs the Good Sauce (and the Church and State Conference). Dave took up my invitation to the table (in that deleted article). We ate together. It was his show I was on where I suggested my issue is that I think our public Christianity should be informed by a theology of the cross.

Dave’s article sensationally declares that this media release is pretty much a declaration of war against all Christians. “Queensland Police just called all Christians “terrorists,” his headline reads — now. They didn’t call me a terrorist because I am not a premillenialist fundamentalist; but apparently all Christians are that…

Dave won’t like this reading of his headline; but I think it’s about as charitable and coherent as his understanding of the QPS statement. Like the others I’m quoting, Dave thinks the shooting was abominable. It’s just, like the others, he thinks the Queensland Police are abominable too holding “hatefully bigoted” views about (almost all) Christians.

This week the Queensland Police labelled the majority doctrine of Christians throughout the world as “a broad Christian fundamentalist belief system known as premillennialism” which, in their hatefully bigoted view, motivated the heinous crime which resulted in two police officers and a neighbour being murdered.

He goes on to use one of his favourite epithets while whipping his favourite whipping boys.

“There is more basis for prepper terrorism in the climate alarmism dogma preached by leftists, globalists and elitists than such orthodox Christian doctrine as premillenialism, so why isn’t the lying harlot media (LHM) blamed for this tragedy?”

This sort of language that paints the media as beastly (in Revelation’s language of the harlot, who rides on the back of the beast) is the sort of language that fuels a view that the police (and media) are demonic forces who should be shot — even if Dave is quick to point out that the kingdom of Jesus is a peaceful kingdom; there is no peace in the way he speaks about these enemies — including the police. He also calls the police christophobes. He says:

Church And State events around Australia are “arming Christians to influence culture”, not with swords or guns, hate or violence; but with clear preaching of the Gospel and Jesus Christ’s will and ways, the Kingdom of God: for the betterment of all humanity, maximal human flourishing and freedom.

It is up to right thinking believers who love their neighbours and nation to understand the times and not sit the culture war out.

Just about every one of these articles quotes a Martyn Iles Facebook post in response to the Queensland Police. He too, in that post, made the point that true Christianity has no place for physical violence; but he, too, offers more fodder for the culture war.

We’re living in clown world.

In Ancient Rome, the authorities blamed Christianity for the evils of their day because they either hated it, or were totally ignorant concerning it.

I call on Deputy Commissioner Linford to point out where in premillennialism there is any authority given whatsoever for a person to use premeditated violence.

She can’t, because there isn’t.

This is the same Martyn Iles who, on the platform at one of Dave Pellowe’s events, joked — and I’m happy to concede he was joking — in a conversation reported by the Herald:

Mr Iles joked that his father often said “we need a good war” to sort this out and “there’s a little bit of truth in that”, because society would not be so concerned about climate change or gender identity if we were at war with China.

Mr Pellowe then interjected: “We’re not advocating violence or revolution … today.”

Mr Iles added: “Not yet, that’s down the line.”

I’ll make my point as briefly as I can.

- All these commentators are accusing the institutions of this world — the government and the police — of a beastly agenda against Christians; of being something like the Roman regime at various points in its history, engaged in an evil anti-Christian (dare I say ‘demonic’) campaign.

- All these commentators are suggesting we have been badly misunderstood if people think faith can lead to violence.

- All of these commentators are advocating a culture war while knowing that our words might be misunderstood or misrepresented by those who are not Christians.

- All of these commentators are saying the shooters were not Christians. And the violence is never ok for Christians.

I think it is very likely that these not-Christians were fuelled by the sorts of ideas in point 1 — that this is consistent with their words and actions (the evidence gathered by police).

I think it is very likely that these not-Christians were connected to thought leaders swimming within the same ideological ponds as these Christian commentators and that the stuff about demonic agendas (including around the covid vaccines) rang louder and truer than anything said about violence before the shooting. Caldron Pool had ample time between the Eternity article and now to distance themselves from violent warrior language publicly, rather than trying to sue me privately; the condemnations of violence come pretty late in the piece.

I think it is very likely that these not-Christian perpetrators were as confused around language of culture war and demonic opposition as the general public — whether from these sources or others, or just their own reading of Scripture. And that this was part of legitimising their actions. And if you’re going to be a Christian commentator; you have to consider what might occur if you paint the police service as demonic.

So my plea to these commentators is to find a better (and more Biblical) category for public Christianity than culture war.

Find a better way to talk about those who might oppose the Gospel than we are.

Understand the human feelings and motivations behind public statements like this one from the police.

Here’s an idea. The way of the cross.

Martyrdom.

Teach people to turn the other cheek. To love their enemies and pray for those who persecute them. To die at the hands of those wielding the sword unjustly rather than take up the sword. Lose the narratives that even let you joke about violence.

This is not the way of the coward — to not shoot a police officer on your property is not cowardice, and nor is it cowardice to turn the other cheek and not fight back with the political weapons of this world.

Remember that your fellow humans might become deformed images through idolatry, but that they are made by their creator to bear his image and that the Gospel, and finding life in a kingdom not of this world — expressed in the church and its Spirit-filled communities — is the path to their liberation.

Stop demonising your political and religious opponents and start humanising them by responding to any hateful agenda (or innocent misrepresentation) with love.

Start caring about what the coppers think.

Start trying to understand their words the way you would like to be understood.

Four police officers and a member of the public were shot, and three were killed,

Those people are the victims of the Trains decision to shoot — not the church because of how their motives are reported.

They were killed by three people who thought they were serving Jesus and shooting demons as they pulled the trigger.

Those thoughts didn’t come from nowhere.

Stop risking turning up in a police investigation next time around; stop calling for culture war and start calling for martyrdom. That’s how Jesus — the dying and resurrecting king — will be vindicated.

In our bodies we carry around the death of Jesus, so that by our lives his life might be made known.