This is talk number seven from a series preached at City South Presbyterian Church in 2024. Unfortunately the recording failed so there’s no podcast or video version of this one.

We have looked at some pretty abstract images in this series as we have thought about picturing the throne room of heaven as we pray — from the bright light of the sun, to fruitful garden paradises, to mountain tops, to temples, to raw fiery power, to that fiery power being where we go for justice rather than taking things into our own hands, and the picture of the slain Lamb ruling alongside this power.

And look, I do not know if any of these have been enlightening for you; if you have been able to imagine entering heaven using these pictures we find in the Bible.

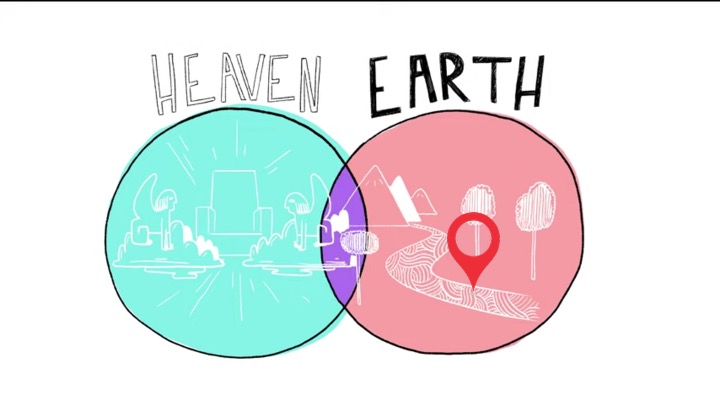

But this has been our goal: to have the eyes of our hearts enlightened (Ephesians 1:18), as we learn to live as those God has raised with Jesus, seating us with him in the heavenly realms (Ephesians 2:6), as we ponder what it looks like to dwell in that reality so we live as those reflecting heaven on earth in this overlap as God’s heaven-on-earth people.

This week I am hoping—maybe—the image we will imagine from the throne room is something more tangible, less metaphorical even, and grounded in the story of Jesus. Mark begins and ends his story with reality tearing moments that demonstrate that the barrier between heaven and earth is thin; and that in Jesus we are seeing what God is like, and what life on earth representing heaven looks like.

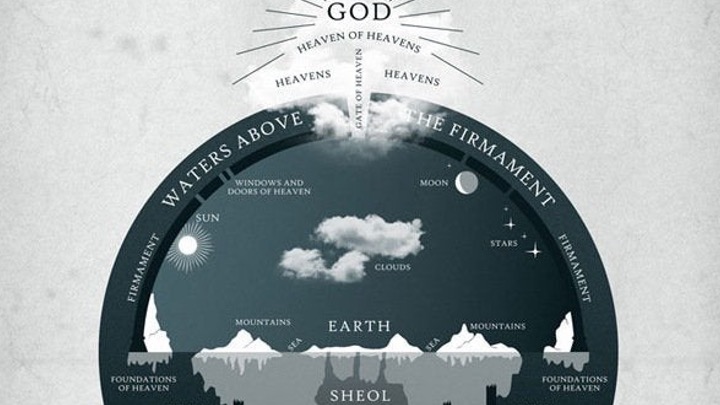

Mark’s story is set up so that we understand it as good news about Jesus the Messiah—the anointed king—the Son of God (Mark 1:1). Now, that title “Son of God” has lots of significance. If you remember Doug’s sermon on Psalm 2, he made the point that this is about a human ruler raised to the throne at God’s right hand ruling over God’s people. If you were a Roman citizen it is language that the Caesars used, building on this idea that Caesar ascended into the heavens and became a god. That will be significant because of what the centurion says at the end of Mark’s Gospel. But whether you think it is emphasising Jesus’ humanity — like with Psalm 2 — or divinity — like with the strange bit of Genesis where sons of God come down from heaven and create the Nephilim — it is pretty clear Mark wants us to see Jesus as a human who bridges heaven and earth; who breaks the barrier between them.

Mark brackets his story of Jesus with these two reality-tearing moments in what’s called an ‘inclusio’. There is an interesting similarity being drawn out here: the heavens are torn open so that God can enter the story in the form of his Spirit at the baptism of Jesus, and the curtain that represented the barrier between heaven and earth — between holy space and the most holy space of God’s throne room — is torn open from top to bottom (Mark 1:10, 15:38).

This shows Jesus to be the promised Messiah who will baptise with the Holy Spirit (Mark 1:8), creating more human bridges between heaven and earth. This is what Mark’s Gospel sets us up to see as John the Baptist describes the king who is coming.

The scene at Jesus’ baptism marks the dawning of this new reality; it anticipates the curtain tearing as the heavens do tear open, and God’s Spirit descends to hover not just over the waters like in the beginning of the story, but to descend on Jesus to mark him out as a heaven-on-earth human (Mark 1:10).

Then the voice reinforces this message—this is God’s Son, whom he loves, in whom he is pleased (Mark 1:11); a model human. It is a combined fulfilment of Psalm 2 and of the promise in Isaiah of a servant who would lead people home to God (Psalm 2:7, Isaiah 42:1).

Here is the thing—this reality-tearing moment where heaven and earth are overlapping does not just happen here. Reality is altered from this moment. This is the start of God acting to create a people who are at home with him; people living before his throne; a kingdom. This is what Jesus announces his mission is all about: “The time has come.” He is now bringing the kingdom of God (Mark 1:14–15), the overlap between heaven and earth for those who repent and believe the good news of God. This change of reality is what it means for the kingdom of God to come near. And the Gospel story is a demonstration of this reality; a look at what heaven-on-earth life looks like as we see it embodied in God’s Son, the Messiah.

Which is a point we may not see in a bunch of the miraculous stories Mark records. But it is very clear in the transfiguration, where Jesus and his friends are about to go up the mountain and Jesus says, “Some of you—literally the people standing with him—some of you will see the kingdom of God coming with power” (Mark 9:1).

After a six-day wait — echoing the six days Moses waits to go up the mountain into the presence of God (Exodus 24:16) — some of them head up a mountain (Mark 9:2), a heaven-on-earth place, close to the skies, for a taste of the barrier between heaven and earth being gone.

What they see at the top is Jesus transfigured (Mark 9:2).

Now, when you hear the word transfiguration you might be thinking about Harry Potter and the idea of turning something into something else. But what we are seeing here is not Jesus being turned into something else — except maybe his clothes — it is Jesus being revealed as something else; as he really is; as the glory of God meeting humans on a mountaintop. To draw our attention to this, we meet these two Old Testament characters — Moses and Elijah — on the mountain as well (Mark 9:3–4).

There is conjecture about why these two appear, but it seems not so much that they represent the Law and the Prophets, but that they are two who also came into contact with the presence of God on mountaintops (Exodus 24:18, 1 Kings 19:11). Here they are meeting the glorious Son of God face to face. A scene from both their encounters — and one from the baptism of Jesus — repeat: a cloud of glory appears on the mountain and envelops them, and a voice says, “This is my Son, whom I love. Listen to him” (Mark 9:7).

This is the heaven-on-earth human. Mark wants us to see that heaven-on-earth life is not just the baptism; it is the whole life of Jesus—all the way until he is no longer on earth.

So Mark reports this little bit of Jesus’ trial, where he is asked, “Are you the Messiah, the Son of the Blessed One?” (Mark 14:61). And Jesus says, “I am” — a phrase rich with Old Testament meaning. From this point in the story onwards, people will see him not just as the Son of God, but as Daniel’s Son of Man, the ascended human ruler who will join God ruling in his heavenly throne room forever. They will see this: Jesus seated in the throne room at God’s right hand, and coming into that throne room on the clouds of heaven (Mark 14:62).

And in what feels like moments after Jesus paints this picture of glory — a reality he says is where this is all heading — the Messiah is crowned with thorns and then enthroned on a cross, with a sign above his head: “King of the Jews” (Mark 15:26).

The crowd is hurling insults at him — this heaven-on-earth human; a walking temple; a representation of the throne room of heaven — as though the building in Jerusalem stands vindicated, its holy place intact as this happens:

“So! You who are going to destroy the temple and build it in three days, come down from the cross and save yourself!” (Mark 15:29–30).

“Let him come down”… Prove it. Those being executed with him also mock him (Mark 15:32). Right after this mockery there is another heavenly sign: the light stops—the light that is an emanation of God’s glory; God’s light reflected by the sun—goes out at the very time it should be at its brightest. For three hours this period of heaven-on-earth humanity expressed in Jesus is about to close, at least for a while (Mark 15:33).

Then, as the darkness ends, Jesus breathes his last (Mark 15:37). By staying on the cross, God’s Son demonstrates Spirit-filled heavenly life — the nature of the one on the throne. The Messiah shows us what God’s love for us looks like in the face of cosmic darkness, and he shows us that light triumphs. He has come to destroy the barrier between heaven and earth; to make the change brought about in his birth, expressed in his baptism and transfiguration, a permanent shift in the cosmic order. As the one who will give God’s Spirit — his breath — to all people who find life in him, he gives up his breath.

The curtain of the temple tears from top to bottom (Mark 15:38). The story of this heaven-on-earth life —at least as Mark tells it — is bracketed together, and everything that has been done so that God’s heavenly life can spill out of the holy of holies and into people throughout the world has happened. This is not just about us being able to come into God’s presence in that place in the heart of his temple, to live before his throne. It is about God’s presence coming to dwell in us as his Son launches the kingdom of God, the kingdom of heaven for all who turn to him and believe and receive this gift.

At this point the Roman centurion, who has been schooled for life on the idea that the ascended Caesar is the god-king who brings heaven on earth through his sword and power, sees something in the crucified, bloodied, beaten, crowned man in front of him that convinces him: “Surely this man was the Son of God” (Mark 15:39).

This is the king. This is heaven on earth.

I do not know if you are in the habit of reading the Gospel as a picture of heaven on earth, where Jesus is a kind of walking expression of God’s heavenly rule — his throne room. But there are clues in John’s Gospel too.

When John talks about the Word who is with God and is God becoming flesh — this is a heaven-meets-earth reality. When he says the Word made his dwelling among us, this is the word tabernacle — a mobile throne room reality. And when he says we have seen God’s glory when we see Jesus (John 1:14), this makes the connection clear.

John records the same promise that Jesus will baptise with the Holy Spirit at his baptism (John 1:33). But the heaven-opening stuff does not stop there. He also has this strange picture of angelic beings — like the cherubim and seraphim we have met in the last couple of weeks—ascending and descending (John 1:51), flying around Jesus, as a way of opening our eyes to the parallels between his life and the heavenly throne.

Then Jesus talks about his body as a temple (John 2:14, 21), and about living waters flowing from him to give life to the world. John explains he is talking about the Spirit (John 7:38–39). This is imagery we have seen in the temple as a heaven-on-earth picture of God’s throne room that reappears in Revelation as a source of divine life.

John uses all this to build to the idea that Jesus is the way into life with the Father, and even that when we have seen Jesus we know him and have seen him (John 14:6–7). When one of his disciples is confused, Jesus simply says: “If you have seen me, you have seen the Father” (John 14:9).

So as we imagine coming before the Father — before his throne — there is no better picture of the God we are approaching in prayer, who is approaching us in love to answer our prayers as he creates heaven-on-earth people, his kingdom, than Jesus himself.

We have talked a bit about meditation or contemplation from this book Meditation and Communion with God. I do not know if you have found this helpful — I really have. The idea is to take propositional truths from the text of the Bible — things we believe to be true — and pair them with images we get from narratives or poetry.

So if we were to take the proposition that we have been raised and seated with Jesus and can set our hearts on things above, where Jesus is at the right hand of God (Colossians 3:1), it makes sense to find ways to picture Jesus in this position as we believe this truth. This is a visual we are given multiple times as we contemplate the things above.

The writer of Hebrews tells us the Son is the radiance of God’s glory (Hebrews 1:3). If we want to picture that bright light glowing out into the world — Jesus is part of that picture. More than that, Jesus is the exact representation of God’s being. If we want to picture the God who is ineffable, beyond our categories or descriptions, Jesus is the bridge — the image. Now that he has made purification for sins, opening the way to be before God’s throne without his power consuming us, he is seated at the right hand of the Father. The heaven-on-earth human is now the human-in-heaven ruler. The Son of God is the Son of Man.

Hebrews keeps telling us to fix our eyes upon Jesus (Hebrews 12:2). But what does it look like to do this? One way is to look at stories about Jesus — the things he does as a heaven-on-earth human — and know that this same heaven-on-earth human is now ruling in heaven.

Not only is he there advocating for us as we pray, he is the perfect representation of the God we pray to — of his character and desire. Through him we approach the heavenly Father, united with the Son he loves, in whom he is well pleased, and through the Spirit dwelling in us — so that we are members of his kingdom, his family.

So let us run quickly through some scenes in Mark’s Gospel. I want to encourage you to pick a few, and as you pray, picture God being like Jesus in this picture, and Jesus being like Jesus as he advocates for you. There is a real intimacy and tenderness in many of the ways Jesus shows us what heaven on earth looks like between those heavens-tearing moments in Mark’s Gospel. Notice the posture of Jesus in these stories — how much they involve loving, tender touch. Touch that does not harm but raises up, even as it demonstrates the raw, creative, evil-destroying power of the throne of God.

In Mark chapter 1, Peter’s mother-in-law is in bed with a fever. When Jesus hears about this he is at her bedside immediately. He takes her hand — presumably gently, like one would take the hand of an elderly woman who is unwell — and he helps her up. He does not pull her violently, he helps her. And she is healed (Mark 1:30–31).

A little later a man with leprosy begs to be made clean — to no longer be horribly afflicted or socially isolated, untouchable. Jesus reaches out his hand. He is indignant, not at the audacity of this untouchable man asking for help, but at the disease itself. He reaches out his hand and touches him, willing to overcome the barrier — healing, cleansing, restoring him to life in community (Mark 1:40–41).

This is the Jesus who advocates for us as we approach the throne room of God, praying to be healed and restored — from sin and alienation from God, and from sickness and alienation from others. Jesus, with hand outstretched, is the image of the God on the throne.

Or there is the paralysed man lowered through the roof, where Jesus, at the sight of the faith of him and his friends, forgives his sins — before healing him with a word (Mark 2:5).

Or the Jesus who is powerful over the wind and the waves — the chaos terrifying his beloved friends—who stills the storm with a word (Mark 4:39).

Or the Jesus meeting the grieving mother and father of a child who has died — who takes her by the hand and speaks, telling her to get up. And she does. This is the Jesus in heaven who comforts us in our terror and grief, who speaks for us, and who offers resurrection hope to us in the face of death and the ferocious power of a hostile world (Mark 5:40–41).

Or the Jesus who uses his hands to break bread and then hand it out to feed multitudes (Mark 6:41), who teaches us to pray “Give us today our daily bread.” This is the Jesus who is raised and seated with God, who sends bread.

The Jesus who, as he walks the earth, is touched and held by so many who are healed as heaven meets earth (Mark 6:56).

The Jesus who places his hands on the deaf man who cannot speak, his fingers in his ears and on his tongue, and heals him (Mark 7:32–33).

The Jesus who touches a blind man and restores his sight (Mark 8:25).

The Jesus who, in the face of an evil power — a demon seeking to destroy a child, throwing him in fire or water — takes the boy by the hand and lifts him to his feet. The opposite of the evil power, who throws him down. Jesus takes him by the hand, lifts him up, delivers him (Mark 9:27).

And then a little later, he gives a picture of life in the kingdom of God — heaven meeting earth — when he takes children the disciples try to keep away into his arms and says: “Truly I tell you, anyone who will not receive the kingdom of God like a little child will never enter it.” Prayer is like this — coming to the one who embraces us in his arms like children, offering nothing but prepared to receive everything (Mark 10:15–16).

And then, in that moment where reality shifts forever — in the lead up to the curtain tearing — Jesus is crucified (Mark 15:24). His arms are spread wide open on the cross, nails driven through those hands. The hands that now stretch out to us, as in all these stories, are scarred by nails. The slain Lamb is on the throne.

As we set our hearts on things above, as we imagine not just Jesus, but through him the nature and character of the God who rules — he rules with hands outstretched and arms open to receive us. To receive you.

Can you picture this?

What would happen if you prayed with this picture in your head?

That is a profound picture — a revolutionary picture — for us. To have the God who created the universe, who flung the stars into space, open his hands to receive us as we pray. How could we not pray?

The life of Jesus, as Mark tells it, is good news. It is a revolutionary moment where we see what heaven on earth looks like; what a walking throne room looks like; what the one enthroned looks like. It is an invitation through the torn curtain to have access to the throne. But it is also, through the torn curtain and the gift of the Spirit, a picture that frees us to offer the same posture to the world that he has to us: arms outstretched in love, offering embrace, and the chance to experience the kingdom of God through us.