The fallout from Israel Folau’s un-nuanced (both theologically and pastorally) comment on social media last week continues. Lines have been drawn. On the one hand, he’s become a champion for free speech and religious freedom, amongst pastors, political conservatives, and Libertarians… on the other, he’s become a homophobic ‘demon’ in the eyes of atheist commentators (and former Wallabies), sponsors, and the LGBTIQ+ community.

Sydney Anglican Archbishop, Glenn Davies, said:

“Israel Folau should be free to hold and express traditional, biblical views on marriage and sexuality without being penalised, just as other players have spoken out with their differing views…”

Peter FitzSimons weighed in on why ‘religious freedom’ shouldn’t cut it (along with this, he asks some legitimate pastoral questions about the way Folau’s un-nuanced answer might cause damage, that are worth hearing and heeding):

“…the greatest of all rugby values is inclusion. We want everyone on board: white, black, tall, small, fat, thin, abled, disabled, straight, gay, men, women, young, old, etc. Saying gays will burn in hell really is anathema to that. What has shielded Folau from a stronger reaction, so far, of course, is the ‘‘freedom of religion’’ line.

See, if any other famous sportsperson had said: ‘‘I think people who are gay should be roasted on a fire forever more, because, well, that’s just what I think,’’ their own lives would be hell in an instant. It would be classic homophobia, and we just don’t do that shit any more, and certainly not in the public domain.

But, if you say: ‘‘I seriously believe, as a grown adult, that there is a really good supernatural being, called ‘God’, in a paradise above the clouds called ‘heaven’, and a really bad one beneath us, called the ‘Devil’, living in ‘hell’, and though God must have created some beings as being attracted to their own gender, because he created everything, he still so hates his children for having that same-sex attraction, he will send them to hell …’’ we’re all meant to back off.”

MP Tim Wilson, a gay man with a particular expertise in human rights (and the way they bump against each other), and some strong opinions on the necessity of religious freedom came out in defence of Folau’s right to say things he disagrees with…

“Respecting diversity includes diversity of opinion, including on questions of morality… Targeting Folau falsely feeds a mindset that he is persecuted for his opinions. Everyone needs to take a chill pill, respect Folau’s authority on the rugby field, and also recognise that he is employed in a profession that values brawn over brains… It is ridiculous for sponsors to walk away from Rugby Australia because of Folau’s opinions,” he says. “Companies have the freedom to sponsor organisations that share their values, but it would be absurd to make a collective sponsorship decision based on an individual player who isn’t hired based on his opinions. If Qantas and other sponsors punish Rugby Australia they’d be saying Australians can’t associate with them if they have religious or moral views.”

Folau, himself, has tweeted since the scandal, suggesting that he is being persecuted for righteousness. I see his point, in that he has attempted to speak truth about the eternal destiny of a segment of the community, and what could be more loving and righteous than that… and yet, I don’t think he answered the question well — and my problems with his answer are largely aligned with the pastoral objections FitzSimons raised:

“But whatever happens, you must reflect on the effect your words have most particularly on troubled teens – many of them, undoubtedly in your own community – struggling with their sexuality.

Do you have the first clue of the agonies they go through? Do you know how those agonies must be compounded by a respected figure like yourself saying they deserve to burn for all eternity? Most of us can laugh off such nonsense. But what of the kids who are 14, raised in it, and born gay? What of them right now, Israel? How can you visit such pain upon them?”

This is exactly why I think Folau should’ve been much more careful not to create (or legitimise) a separate category of person called ‘gay people’ — while sticking with his truth claim that those who reject God face death and judgment, while those who turn to God (repent) are given eternal life through the loving sacrifice of Jesus. It would’ve been nice for his response to be about good news — that we are all sinners who face a shared future without Jesus, but God loves all people enough to offer us a way out… Jesus’ love is for gay people, straight people, and “white, black, tall, small, fat, thin, abled, disabled, straight, gay, men, women, young, old, etc” — he’s much more inclusive than the Australian Rugby community (who only want you if you love Rugby).

If there’s one thing you can bet on in the current political climate it’s that haters are gonna hate; or polarisers are gonna polarise. On any issue. The collective ‘righteous mind’ kicks into overdrive on any issue that can be turned into a political football that can serve a cause.

We’ve lost the ability, as a community (and as individuals) to talk about things that matter — rather than how we feel about things that matter.

But here’s the thing… Debates about free speech, freedom of religion, and the polarised nature of any public conversation in the current environment are getting in the way of our ability to exercise free speech, and religious freedom, and to actually have conversations about things that matter… and maybe what we should do is just model those conversations, rather than speaking about why they’re important. Obviously all these issues are like a scrambled egg; and they’re very difficult to unscramble… but we perpetuate the scrambledness by scrambling to talk about those secondary issues and how this is an exemplary case, rather than dealing with this as a legitimate public conversation that needs having.

We shouldn’t really get bogged down into the conversation about whether or not Folau should be allowed to say what he says (clearly he should), our time would be better spent on whether or not what he says is true or helpful. The best way to honour his speech and legitimise it, is to engage with it.

If we make religious freedom, or the freedom to not be offended, or popular community held beliefs the issue we discuss in the fallout of Folau’s comments, and not their substance, we’ve already lost. The conversation about what sort of speech we should allow is a ‘secondary’ matter; and it fills almost all the airtime that we should be given to the primary matter; if we had public conversations well (and if we’d stewarded our place in public conversations better in the past) we wouldn’t have to spend all this time talking about what is or isn’t acceptable. If Folau is being ‘persecuted’ because people are trying to exclude him from the public conversation, then the LGBTIQ+ community has been, historically, persecuted in exactly this way in Australia for years; excluded from conversations about what is good, true, and beautiful, when it comes to life in this world…

What’s really at stake here is a conversation about whether there’s any legitimacy to religious belief, or any possible truth at the heart of Folau’s view of the world, and the default assumption from people like FitzSimons is that there isn’t — and that such speech has no place in the hard secular world we now live in, by making the case for free speech, or religious freedom, rather than for religious truth (or even the legitimate place potential religious truth has at the table in a pluralistic society), we’ve allowed FitzSimons and others to move the goalposts from a world that may include a transcendent reality, to a world where only matter matters — a material world.

The tragedy here, is that whatever truth, or untruth, or lack of nuance there might be at the heart of the substance of Israel Folau’s comment on the eternal future of ‘gay people’ gets lost in the noise. And I’d have thought the possible eternal destiny of anybody was maybe worth pondering before we jumped in to temporal tribes and started beating the stuffing out of this football in order to score as many points against the dreaded ‘other’ as possible.

It’s one thing to talk about what Folau got right, or wrong, it’s another thing entirely to argue about whether he was right or wrong to say it; and whether such speech should be allowed; I fear that we Christians have jumped into the second conversation, rather than showing why the first type is actually profoundly good and valuable to our society.

This isn’t about religious freedom; or it shouldn’t be. It should be about whether or not Folau’s statement is true.

We’ve jumped to asserting that Folau should’ve been able to say what he believes, rather than trying to establish the goodness, truth, or beauty of what the Bible actually teaches about life, death, and judgment — about the potential eternal destination of all people.

We’ve, by default, slipped into discussions of a temporal, or immanent, nature — political or secular concerns — rather than talking about things that are transcendent or spiritual. Which is to play the game on the wrong terms; to adopt a ‘limited end’ or a truncated, flattened, vision of the world.

How will we then pull back the curtains of reality and try to talk about the substance, and the legitimacy of ‘transcendence’, if first we’ve adopted a posture to this conversation that makes the important bit ‘should Folau be allowed to speak’ rather than ‘was Folau right in what he said’?

Isn’t the latter of much more importance to everyone?

Isn’t that importance what actually legitimises the offence his free speech may have caused?

I’ve always loved the way atheist magician Penn Jillette (who often reminds me of Peter FitzSimons) responded to being given a Bible by a man who believed he was going to Hell…

“It was really wonderful. I believe he knew that I am an atheist. But he was not defensive, and he looked me right in the eyes and he was truly complimentary, it didn’t seem like empty flattery… and then he gave me this Bible. And I’ve always said, I don’t respect people who don’t proselytise. I don’t respect that at all. If you believe there’s a heaven and hell, and people could be going to hell and not getting eternal life, or whatever, and you think, well, it’s not really worth telling them this because it would make it socially awkward, and atheists who think that people shouldn’t proselytise ‘just leave me alone and keep your religion to yourself’ — how much do you have to hate somebody to not proselytise? How much do you have to hate somebody to believe that everlasting life is possible and not tell them? I mean, if I believed, without a shadow of a doubt that a truck was about to hit you, and you didn’t believe it, and that truck was bearing down on you, there’s a certain point when I tackle you… and this is more important than that… this guy was a really good guy… he was a very, very, very good man… and with that kind of goodness, it’s ok to have that deep of a disagreement, I still think that religion does a lot of bad stuff, but in the end, that was a good man.”

I’ll be banging on about Jonathan Haidt’s The Righteous Mind for some time, I reckon, but his work on moral psychology and the way we polarise and how dangerous that is, should be a must-read for anybody interested in public conversations and civility. Here’s a quote that I reckon cuts both ways in the fallout around Folau — the public conversation is full of blind people with different views of what is sacred, and so different participants who see the ‘other’ as deluded.

I call it a delusion because when a group of people make something sacred, the members of the cult lose the ability to think clearly about it. Morality binds and blinds. The true believers produce pious fantasies that don’t match reality, and at some point somebody comes along to knock the idol off its pedestal. — The Righteous Mind, page 33-34

When he says this he’s not talking about religious delusions, but the common Western myth that the rational mind is a bigger deal than ‘the passions’; the “worship” of reason in western philosophy, it’s not a long bow to draw to make a connection between the worship of reason and the modern western blindness to the possibility of transcendence, or supernatural or religious truth (though Haidt, himself, is not religious). He talks about this tendency we humans have to hold things as sacred, and what that means for our ability to demonise the other in a way that explains the zealous and religious nature of the fallout around Folau’s comments, from FitzSimons, Qantas, and the rest, as much as it explains Folau’s comments.

Whatever its origins, the psychology of sacredness helps bind individuals into moral communities. When someone in a moral community desecrates one of the sacred pillars supporting the community, the reaction is sure to be swift, emotional, collective, and punitive. — page 174

Haidt makes the point that rich, robust, committed disagreement — deep disagreement like Jillette talks about — is actually vital for the pursuit of truth and goodness; but this requires people speaking from conviction in conversation together with people who hold different convictions, not speaking about civility, or pursuing some sort of uniformity of opinion and declaring that civil. He says we need to listen to people who don’t think like us if we genuinely want good outcomes.

“… each individual reasoner is really good at one thing: finding evidence to support the position he or she already holds, usually for intuitive reasons. We should not expect individuals to produce good, open-minded, truth-seeking reasoning, particularly when self-interest or reputational concerns are in play. But if you put individuals together in the right way, such that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, and all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system. This is why it’s so important to have intellectual and ideological diversity within any group or institution whose goal is to find truth (such as an intelligence agency or a community of scientists) or to produce good public policy (such as a legislature or advisory board).” — Pages 104-105

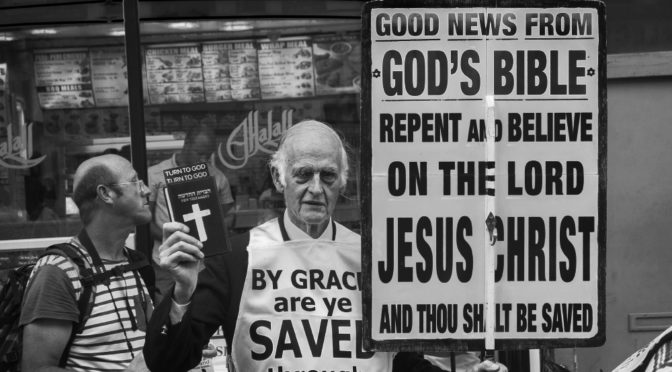

When it comes to middle aged white atheists and their concerns about people talking about Hell, we need a public conversation shaped more by Jillette than FitzSimons. The only way for us religious types to get there is to be more like that bloke with the Bible.

Image Credit: Flickr user Tim Snell, under Creative Commons license