This is an edited transcript of a sermon on Matthew’s Gospel from City South Presbyterian Church in 2022. You can listen to the sermon here, or watch here. The running time for those options is 35 minutes.

What are you praying for — and what would the world look like if your prayers were answered?

If, as the old saying goes, our eyes are a window to the soul, our prayers, I think, are a window on what we think heaven, whether God’s version or ours, looks like…

Our prayers, like our eyes, shape how we live, the heaven we are hoping to create on earth. You might have heard people dismissing “thoughts and prayers” as an alternative to actually doing something to fix problems with the world.

But Jesus challenges that idea…

He has been talking about the good news that the kingdom of heaven is arriving (Matthew 4:17, 5:3, 10, 19, 20).

And now he is talking about what that means when we pray (Matthew 6:5-7).

And how to pray as part of his kingdom (Matthew 6:9).

That is what the Lord’s Prayer is — a prayer for God’s kingdom to come — and a description of what that will look like — his will being done on earth as it is in heaven (Matthew 6:9-10).

Is this how you pray?

Not just repeating the Lord’s Prayer as a ritual — but praying the way Jesus teaches us to pray — for God’s kingdom to come?

There is lots to unpack here, starting with where Jesus locates the Father — and so directs our hearts and eyes and words as we pray…

Our Father in heaven…

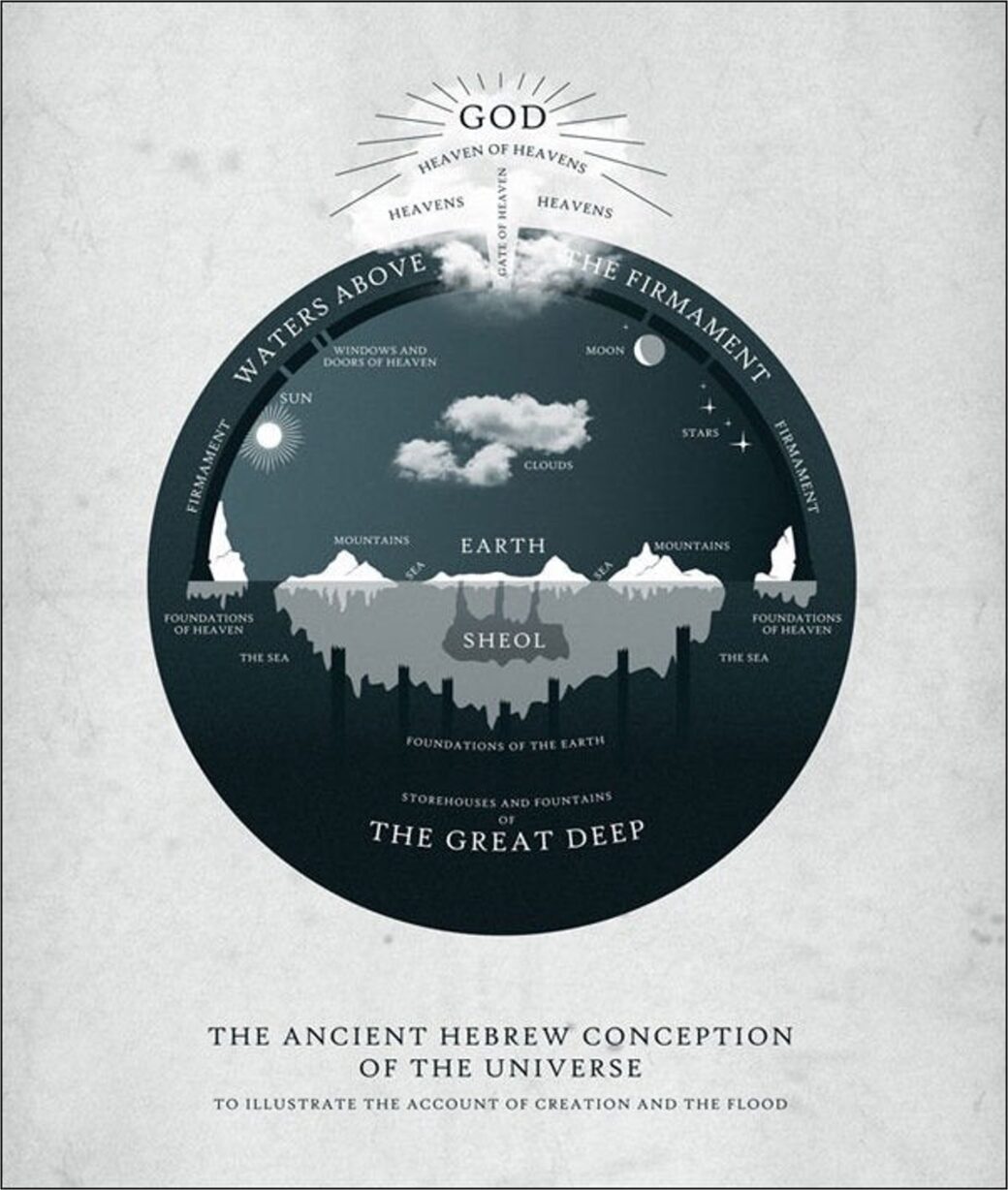

Now we have done plenty about heaven and earth in the last couple of years — this idea that there is this realm — the heavens, where God rules as the Most High, and where there are beings who do his will in heaven — and some who have rebelled — and there is this mirror situation on earth.

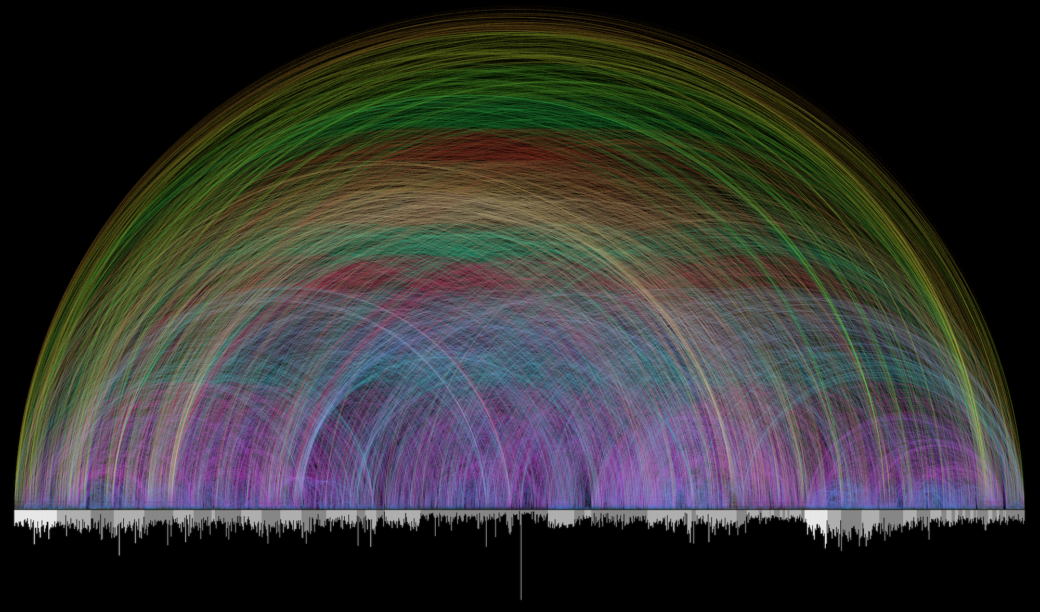

God created both “the heavens” and “the earth” in Genesis 1, and both are brought together in Revelation 21… And the story of the Bible — and the Gospel — is the story of how that happens.

And when we pray “your kingdom come,” it is an acknowledgment that this has not fully happened yet, but that this is the story we are brought into.

We are not just praying for the end of the story, though, but the here and now, as well — for bits of God’s bringing heaven and earth together to break out in little pockets…

Little cities on mountains…

We are praying that God’s will might be done on earth as it is in heaven — through people partnering with him, representing him as image-bearers who reflect the heavens in the earth.

We have seen how mountains play an interesting role in the story of the Bible — that Jesus is on a mountain while showing people how to pray is significant…

The short version of what we have seen so far is that mountains, high places, are meeting points between the heavens and the earth.

And through the story, mountains are where people go to be in God’s presence…

Even right from the beginning in Eden — which the prophet Ezekiel calls the holy mount — have you pictured Eden on a mountain (Ezekiel 28:13-14)?

When Israel passes through the Red Sea in Exodus, escaping Egypt and starting their journey to live as God’s people among the nations — his kingdom — they sing about how God is going to plant them on a mountain — the dwelling place God made for his dwelling… A sanctuary (Exodus 15:17).

And on the way, we get those mountaintop scenes, meetings between Moses and God, where Moses speaks to God, then brings his shining glory down to earth (Exodus 19:11).

Then, when Solomon builds the temple on the mountain in Jerusalem — God’s dwelling place on the mountain he chose as Israel’s dwelling place — God’s glory descends into the holy of holies.

He prays that God’s name would be present and glorified — that God’s eyes would be opened toward the temple on the mountain so that he would hear prayers people pray towards the temple. The temple is a sort of meeting place with God, so prayers make their way through it, to the heavens as people prayed mountainwards (1 Kings 8:29).

Solomon asked God to hear, from his throne in heaven, the voices of his people when they pray, and then to forgive (1 Kings 8:30).

The kingdom of God comes down from heaven, and in the Old Testament, the mountain is a sort of bridge where his dwelling place is placed so he can hear our prayers…

And this might seem like just a little geographic detail we get, a physical setting, but Jesus, the new Moses, a son of David who will bring a new temple and kingdom, is on a mountain talking about the kingdom of heaven turning up…

And a “town on a hill” — which is a pretty understated way the NIV puts it. It is actually the same word used for where Jesus is sitting — and this could be translated city on a mountain — which is a good name for a church (Matthew 5:1, 14).

This is a heavenly city that Israel anticipated, not just coming out of Egypt in the Exodus, but coming out of exile…

Jesus is talking about a restored holy city, a place where heaven comes down to earth… God’s kingdom come (Matthew 6:9-10)… Like in Revelation… but people who live as citizens of that city now…

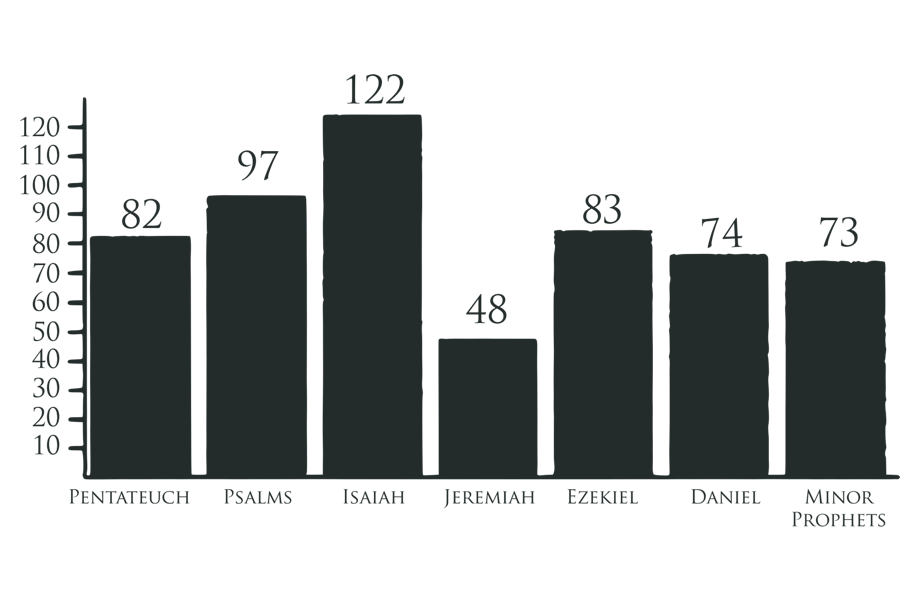

He is talking about the prophets being fulfilled.

You are either bored with this mountain talk, or you cannot wait to go climb one… but here is a fun thing: where Ezekiel, who gets called the son of man, is told to prophesy, not to the people, but to the mountains themselves (Ezekiel 36:1-2).

The enemy thought he had the ancient heights — and maybe we saw a little of this in Satan’s mountaintop temptation of Jesus. But God is still in control. And he has plans to reconnect the heavens and the earth.

Plans for the mountain dwelling of God — where people will be fruitful and multiply as they dwell on the mountain (Ezekiel 36:11-12). This is Eden language; A mountain garden where people live — and fruitfully multiply.

We skipped this bit of the Lord’s Prayer — hallowed — holy — be your name — but it is also a picture of what God’s kingdom does, like the temple — glorifies God’s holy name.

God’s people failed to make God’s name holy. And this is exactly why they are in exile…

Ezekiel says Israel was booted from the mountain, dispersed down into the nations for worshipping idols, instead of drawing the earth up the mountain to God (Ezekiel 36:19-20). Then, out in the nations, they kept profaning God’s holy name rather than glorifying him; they gave him a bad name on account of their actions, and the consequence is exile. Now, the restoration of the kingdom will be God’s doing. He would bring them back; they would not choose to make his name great. God acting to save means all glory would clearly be for him — so that his name would be hallowed once again — he says, “I had concern for my holy name,” and, “I am going to restore you for the sake of my name, as a witness to the nations where Israel has been profaning it” (Ezekiel 36:21-22).

He will show the holiness of his great name — which is why this is something we pray for, rather than something we do to get a pat on the back (Ezekiel 36:23).

It has to be God’s doing so that the nations will know that God is the Lord.

As he gathers back his people — those exiled from the Eden mountain and the Jerusalem mountain — and recreates them as his city on a mountain (Ezekiel 36:24).

He will put his Spirit in people — so it is clear he has done the recreating; the restoring; the saving (Ezekiel 36:27-28).

That it is not on us, it is not our choice, there is no glory for us in this… God will recreate. God will put his Spirit in people. God will put them in the land — just like he did in Eden and Jerusalem…

God will be God. And everyone will know it. His name will be hallowed. And the mountains will become like Eden, there will be this new city (Ezekiel 36:35). A new Eden; heaven and earth merging together under God’s rule. And if we repent and prayerfully follow God’s King, we will get to live there. With God.

But now, like Israel between Egypt and Jerusalem, we live with that hope, but also with God’s presence leading us on a journey. We are not exiled from God anymore, or even exiled and being trampled by the forces of darkness. We are citizens of heaven on a journey with God to this destination, which means, like Israel in the wilderness, we rely on God to sustain us, providing our daily bread (Matthew 6:11).

This can be read literally — that it is about food. And it is not less than food; Jesus will go on to talk about God delighting in providing for our needs.

But bread in the Gospel stands for God’s good provision for his people. Jesus gives heavenly bread through the story, like when he feeds the 5,000. And the literal wording of this verse is actually something like “give us the bread of tomorrow today” — and that can be read eschatologically — as though it is about the future — the feast with Jesus in the kingdom. And that is also a good thing to be praying for.

And it can also be read Exodusly—as a prayer for provision of heaven in the here and now. There is already bread from heaven in the story of God bringing his kingdom of heaven to earth; back when that was Israel’s job. In the Exodus, when God sent bread from heaven to provide for his people (Exodus 16:4).

In this story, there was even a bread of tomorrow—bread collected the day before the Sabbath as a reminder of the holiness of God’s Sabbath rest (Exodus 16:23); a little taste of Eden and God’s provision to his people without their need to work the ground.

On that day, God gave “bread for two days”—the “bread of today” and the “bread of tomorrow” — bread of rest (Exodus 16:29-30). So maybe that is part of the ‘bread of tomorrow today’; a prayer for not only provision but Sabbath rest; a prayer for Eden-like “heaven on earth” — relying on God’s provision and hospitality, to take His presence into the world—like when God gave people fruit trees and said “be fruitful and multiply” and “take and eat.” Even this prayer for bread is not simply a prayer for food—but a prayer for heaven to break into earth, for Sabbath-like Eden life with God. For God to give us life.

We will see a couple more ways this is fulfilled as Jesus shows us what an answer to His own prayer looks like. But just briefly — Jesus’ prayer moves into how God’s kingdom coming for us— via forgiveness of sin — impacts how we live as his people as we pray this prayer, as forgiven people who forgive others (Matthew 6:12). And how life in the kingdom means following his example, rather than Adam’s and Israel’s—the examples that lead to exile from the mountain — and left Satan thinking he was king of the mountain — right up till his failure to tempt Jesus — so we pray that we might not fall into temptation, but be delivered from evil, by God, in order that his name be glorified (Matthew 6:13).

I wonder if you have ever pondered—whether reading or praying these words—what it would look like for your life if God answered them.

Well, an easy answer is that it would look like the Sermon on the Mount being put into practice… because it looks like Jesus. God’s King, arriving to end our exile from God and restore God’s kingdom — God with us — bringing the forgiveness of sins, and restoring God’s name.

Jesus is both the pray-er and the first picture of what the answer to the prayer looks like.

We might pray for the bread of tomorrow, the bread of heaven, a taste of the heavenly feast, salvation—like in the Exodus—at the Passover.

Jesus gives us the bread of heaven, not only the bread on the table at the meal, but his body, given for those who will join his kingdom; God’s life (Matthew 26:26).

We might pray “Your will be done” when we pray the Lord’s Prayer; these words are on the lips of Jesus as he prays before he goes to the cross (Matthew 26:39).

To bring the forgiveness of sins — God’s forgiveness of us — through his blood, the blood of the covenant, poured out for many for our forgiveness (Matthew 26:28).

For Jesus, prayer is not empty. It is not doing nothing. These words shape his life. They see him give his life to seeing God’s kingdom coming… to fulfill the prophets, as a new King, who leads us on a new Exodus as we journey with him until the end of the age. When Jesus teaches us to pray, it is not a choice between praying or doing something; it is about praying in a way that gives ourselves to God, because God gives us the bread of tomorrow — his life in us.

And one more bonus Ezekiel fulfilling fun fact—it is not in Matthew, but in the story of Pentecost.

Pentecost was a festival of bread. At Pentecost, the people who have put their trust in the risen and ascended Jesus, who rules in the heavens, are filled with the Holy Spirit (Acts 2:1, 4, 33).

And Peter says if we hear Jesus’s command to repent and be baptized in the name of Jesus, we receive both the forgiveness of sins and the Holy Spirit; becoming bridges between heaven and earth (Acts 2:38). The prayer is answered in us as God’s kingdom comes.

We do not have a tradition in our church community—or, so far as I have gathered, in the Church of Christ—of praying the Lord’s Prayer in our gatherings, or probably regularly in our lives. So let’s come back to what you are praying for.

Do your prayers look anything like the prayer Jesus teaches? Does your version of the kingdom of heaven breaking into earth look like His?

Does your life—shaped by your prayers—look like His life?

If it does not—and when I think of my own prayers—they sound nothing like the prayer Jesus teaches—they are often not even shaped by the prayer Jesus teaches, let alone my life lived as I seek to see my prayers answered.

And if that is you too, then we need to repent.

It is one thing to try to avoid the empty ritual of praying the Lord’s Prayer, thinking it is a template for fresh expressions of prayer—that we can do better in our own words—that might be fine if we actually were doing better.

So maybe we need to ask if what we have pushed away as empty rituals are actually practices and words—a bit like the creed—that give us a reality-defining, life-shaping language. What if these are words that give life?

Maybe it is not the repetition of these words that makes them a dead ritual, but that we do not have the incredibly rich reality behind the words in mind as we pray for a new Eden, for the end of the world’s exile from God—for our lives to be radically transformed as God’s kingdom comes on us, by the Spirit, so we might do his will and radiate with his glory.

If you want one take-home application from today—one practice—try praying the Lord’s Prayer multiple times a day, with this big vision—this story of heaven and earth being fused together shaping your heart as you pray; not dead letters or an empty ritual, but a living word that will shape your life as God answers your prayer. See what happens to you.

The idea that prayer does nothing only works if, when we pray, God does nothing to us, but also if, when we pray, we then do nothing from lives and hearts shaped by God answering our prayer…

This is a prayer embedded in the Sermon on the Mount; praying like this is a practice we are commanded by Jesus to embrace. As God’s city on a mountain — his kingdom coming as we prayerfully seek his will—bringing glory to Him through our good deeds as we are freed by Jesus to practice his righteousness as we imitate the way he lives as citizens of his kingdom.

The reason Jesus gives for praying like this is to live for God’s kingdom and glory, not our own. It is to avoid the hypocrisy of those claiming to live for the kingdom of heaven, but really living for the kingdom of earth—the hypocrites we will meet in Matthew (Matthew 6:9).

Prayer is an action, but this prayer without action—the sort of action commanded by Jesus for those in God’s kingdom—is another form of hypocrisy.

Jesus will go on to say that our eyes are what let light in—what shapes our hearts… so that we can reflect the light out (Matthew 6:22).

Prayer is a gazing into the heavens—it is approaching God—and, by the Spirit, it is us entering his court to ask our Father for things…

This is such a profound part of the Lord’s Prayer—that not only does Jesus call God Father, but he teaches us to approach heaven calling God Father… to enter the heavenly throne room and call God Father…

And to do this knowing God is not distant from us, but with us— he sees us, he knows us, and our needs, he rewards his children, he forgives us, he feeds us, and he delights in giving good gifts to us—in giving us a kingdom and his presence with us for eternity as his beloved children (Matthew 6:4, 6, 7, 14, 26, 32, 7:11); and all this brings him glory because he is the one who acts.

God will not just give us bread; he will give us himself—his Son, the Spirit, life with him, a kingdom (Matthew 7:11).

For his glory. What would it look like in our lives if we prayed not just any prayer that looked like the Lord’s Prayer—but if we consistently prayed the Lord’s Prayer?

If we gazed into heaven at God, our good Father, and in seeing his glorious light, reflected that in the world… Setting our hearts on heaven, and so treasuring life in God’s kingdom, storing up treasures there, investing our time and energy there, rather than investing ourselves in the kingdom of earth and things that will fade (Matthew 6:20-21).

We would look like people who seek first his kingdom and his righteousness—the first action in seeking God’s kingdom—to bring heaven to earth, is to enter God’s presence—to pray (Matthew 6:22).

We would look like Jesus. Prayer like this is one of the commands of Jesus we are to practice and teach—as we seek to be “great in the kingdom of heaven”—to be like our King, bringing God’s glory to earth as people saved by him to represent his name (Matthew 5:19).

The Sermon on the Mount ends the way it begins—with Jesus calling us to the wise life; the life lived hearing his words and practicing them (Matthew 7:24).

Seeking his kingdom and living lives shaped by prayerfully fixing our eyes and hearts on heaven, as we await the day when heaven and earth become one and we live with God in a new Eden.

Maybe if you are out of practice praying like this, or praying this prayer, you might join me in doing it in a moment as we share communion together.