This is an adaptation of the third talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, or watch it on video. It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

Last ‘chapter’ we imagined life in an old village. This time I want you to imagine you are living in a monastery in the thirteenth century.

Here is a picture from the dedication of an altar in a monastery in France.

These seven candles on the altar were not just lights; they helped you mark time. You knew roughly — not exactly — how far a candle burned in an hour, so the daily schedule of prayers and meals was not “by the clock,” but “by the candle.”

The rhythms and rules — the daily prayers, weekly rhythms, and the Christian calendar — provided an enchanted framework for life in space and time. These candles were a technology that helped.

They are an echo of the lights in the menorah — a candlestick that held seven candles, seven bowls of oil with wicks that lit up Israel’s holy place.

Israel’s priests had to keep these lights burning from evening till morning every day as a “lasting ordinance” — a picture of space and time to teach Israel its story (Exodus 27:20–21).

The lampstand was made like a golden fruit tree, and people connect it to the tree of life (Exodus 25:31–32).

And the lights were shining in front of the curtain, which separated the holy place from the most holy place, as a picture of the barrier between heavens and earth, with shining heavenly beings — cherubim — embroidered on it (Exodus 25:3, 26:31, 35).

The word for the lamplight is used in Genesis 1, and then repeatedly in the instructions for these candlesticks. It is used for the lights that mark sacred times and days and years, in the vault between heavens and the earth. These are reproduced in Israel’s mini-heavens-and-earth space, to teach people to live in a certain rhythm that reinforces their picture of the universe, and of God (Genesis 3:14; Exodus 27:20).

The act of crafting this lampstand, and keeping these lights alight, is an act of making. This lampstand, and its lights, are a technology that shaped Israel’s physical environment, in the temple, and their understanding of the world (Exodus 25:31–32).

Making things — making technology and art and objects that teach us and shape us — is part of being human; being made in the image of God, to represent him (Genesis 1:26).

The author Dorothy Sayers wrote about this in her book The Mind of the Maker. She says all we know about God when he says we are made in his image is that he makes things:

“When we turn back to see what [the writer of Genesis] says about the original upon which the ‘image’ of God was modelled, we find only the single assertion, ‘God created.’”

Dorothy Sayers

So a characteristic we have in common with God is “the desire and ability to make things.”

To be human is to make things from the world he made, even the gold in it (Genesis 2:15) — to represent and worship him. The task of cultivating and keeping a garden, and then a temple, required tools and technology. There are even instructions in the laws about the wick trimmers; tools made of gold (Exodus 25:38).

We can make temple furnishings that teach us about God and his world. Or, like bricks in Babel and Babylon, we can make things to push beyond our limits against God. Or we can make golden calves:

“He took what they handed him and made it into an idol cast in the shape of a calf, fashioning it with a tool.”

Exodus 32:4

That is the tension for us today. Being human means having the capacity to make technology that shapes the world, shapes how we see the world, and shapes us. That technology will either extend our function as image bearers, or deform us as we make idols. Both these truths are true and we have to hold them together.

And, just for fun, when Jesus is introduced as “the carpenter” in Mark’s Gospel (Mark 6:3), it is the word tekton — a word for craftsman — from the root for our word “technology.” The true human is a tech-maker.

So, back to our monastery, and these candles that taught people about life in the world: light and darkness; life in rhythm with God; as limited people located in space and time. Neither space nor time was split between secular and sacred; it was all God’s. This rhythm of praying the hours, marked by candlelight, provided a framework for life — one that was a little inexact. And if you were a stickler for rules, like some monks, this was a problem.

So in 1283 some monks at a monastery in England, who wanted more regulation, installed a mechanical clock, right above the pulpit in the chapel. That is when people started complaining about preaching going too long…

Historians reckon this might have been the first mechanical clock. It is likely they were invented in a monastery.

Marshall McLuhan is a bit of a hero of mine. He is the guy who said “the medium is the message.” His point was that we think we are changed by ideas — the content of a message — but those ideas are first shaped by the technologies — mediums — we use to understand things. Like with the candles: when we believe we are thinking things, changed by ideas, we neglect how our bodies interact with the world — how what we see and touch and smell and use shapes our thinking, and what we love.

Lots of his thinking about technology was actually built from two Biblical ideas. First, the idea that we become what we worship, and that we shape our tools — technology — and thereafter technology shapes us.

“We become what we behold. We shape our tools, and thereafter our tools shape us.”

Marshall McLuhan

And second, the idea that the incarnation of Jesus is the ultimate communication:

“In Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message. It is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.”

Marshall McLuhan

He believes the clock in the monastery changed our view of time, and space, and was the start of “natural man” giving way to “mechanical man.” The monks’ need for synchronised action in communal life, with a clock regulating prayer and eating times, introduced ways of seeing time that changed what we behold. Time was seen as mechanical, and not observed in sensory and tactile ways.

He says when missionaries brought mechanical clocks to Asia they replaced not candles but burning incense sticks, so time became disconnected from our bodies and senses.

And when mechanical clocks — invented by monks — were installed in town squares they regulated the workday, and brought a new world order, and a new story about the world. Working with factories and engine-driven public transport — like trains — to get whole cities or communities running like clockwork, or like an old-fashioned wind-up robot, an automaton.

“By the nineteenth century it had provided a technology of cohesion that was inseparable from industry and transport, enabling an entire metropolis to act almost as an automaton.”

— Marshall McLuhan

McLuhan traces how this changed how we view space as well, shifting us from an enchanted cosmos to a mechanical universe. During this time, because machines were a powerful model of things working, people started talking about God as a watchmaker. The universe became clocklike.

And this would have been impossible without the clock embedding itself in our image-creating capacity — our imagination. You cannot imagine God as a clockmaker without clocks.

“The mechanical clock, in short, helps to create the image of a numerically quantified and mechanically powered universe.”

— Marshall McLuhan

Humans moved from thinking about God as a triune communion of love, whose love overflows into the world and in creation, to thinking about God as a distant engineer, because we do not just think, but we are people who live in time and space with our technology.

C. S. Lewis’s first public lecture as chair of medieval literature at Cambridge was about the difference between the world in the stories he loved, and the modern world.

He believed Pharaohs in Egypt had more in common with Jane Austen than we do. The enchanted pagan world had more in common with the enchanted Christian world than it does with the post-Christian world. And the big difference is the rise of the machine.

Especially the way with the machine we get a mythology that comes with technology: the idea that the newer and more efficient is always better.

“… a new archetypal image. It is the image of old machines being superseded by new and better ones. For in the world of machines the new most often really is better and the primitive really is the clumsy…”

C. S. Lewis

And while I would not want the medical technology of any time before now, I wonder if this is where the furious tension gets broken. Where we slip into an idolatrous belief that human technology will fix the world. That all change is good, even if it breaks us by pulling us past our limits with false promises that dehumanise us.

Lewis saw this with the car. When people did not have cars they were stuck in the village we imagined last chapter. Their church was the church in the public square. Their neighbour, who they were called to love, was their actual neighbour. Where clocks regulated village life, cars fragmented it, as people could go rapidly beyond the limits of being a body in space.

C. S. Lewis wrote about the car annihilating space. He had this idea that distance is a good gift from God in a vast world, that our limits are actually a gift from God.

“The truest and most horrible claim made for modern transport is that it ‘annihilates space.’ It does. It annihilates one of the most glorious gifts we have been given.”

C. S. Lewis

Technology will always extend or break our limits. That is both a feature and a bug. It is where we end up in Babel-like idolatry, or making tools to feed people more effectively.

But despite the idea we often believe — that technology is neutral and where it takes us is about how we use it — McLuhan has a great line about this idea, calling it the “numb stance of the technological idiot.” Technology is not neutral. It is ecological. It always brings change to our environments, and so to us. If it does not, it is not really a technology.

“Our conventional response to all media, namely that it is how they are used that counts, is the numb stance of the technological idiot.”

Marshall McLuhan

McLuhan’s work was trying to help us think through not just the obvious enhancements brought by technology, but the unseen forces — even at the level of myths and images — that change us and the world.

The monks did not imagine that, rather than regulating time with God, the clock might change how people thought about time and space and God. And maybe, like them, we do not think about how our technology is not just regulating our lives, but changing our imaginations and providing a mythology — a story — we inhabit.

There has been a technological revolution since the mechanical age that has already altered our picture of reality — our mythology — mostly in a closed-off universe. This has been about how we think of ourselves and the universe. People once talked about our brains as machine-like. Now we talk about them as though they are computers — programmed, wired, dependent on data. And people model human relationships as networks, while picturing the universe as a giant super-computer.

Elon Musk already believes we live in a computer simulation. There are more people who think if we are not already, that is the path to immortality.

Remember Yuval Noah Harari from chapter one — the guy who ‘annihilated space and time’ by giving a TED talk as a hologram? The thought-leader who believes we are on a tech-fuelled trajectory to become gods?

“…having raised humanity above the beastly level of survival struggles, we will now aim to upgrade humans into gods, and turn Homo sapiens into Homo deus.”

Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus

He believes engineers — geeks in a lab — not Jesus — will lead us to overcome death:

“We do not need to wait for the Second Coming in order to overcome death. A couple of geeks in a lab can do it. If traditionally death was the speciality of priests and theologians, now the engineers are taking over.”

Yuval Noah Harari, Homo Deus

Now, most of us are not going to buy that obvious idolatry. And even if we were, Harari makes the point that most of us could not afford to, even if we wanted to.

But our lives — as individuals and in community — are shaped by digital technology, and often the devices in our pockets; these tools.

Now it is easy to think these are not just neutral, but good. Try to imagine life without one, and the apps you love, and they feel embedded and almost impossible to uproot. They are genius pieces of technology that feel like they make life easier.

It is much harder to uproot a technology you have adapted to than one you have not. But what if these are disintegrating our humanity? Could you do it? Could you walk away from your phone tomorrow?

When we talk about digital technology it is not just hardware, is it? It is software as well. But this technology is pushing us beyond our limits like never before.

It has its own disenchanting mythology, and view of the future we can buy into. Even if we do not want to digitise our consciousness, becoming one with the machine — we will look at that more next time — there is a future we are all actually living in that wants to see everything connected; a picture of the future where every surface is a touchscreen, and where all our devices — starting with the fridges — are connected to the internet, and watching us.

A smart fridge that auto-orders your groceries by anticipating your desires based on your TV viewing might seem exciting. I want one. But it is also kind of terrifying.

We do not just live in a secular age. Shoshana Zuboff describes the world we live in as The Age of Surveillance Capitalism.

She says there is another tech myth out there — that we are the product. But we are not. We are the patch of ground they buy a mining license for:

“We are the objects from which raw materials are extracted and expropriated for Google’s prediction factories. Predictions about our behavior are Google’s products, and they are sold to its actual customers but not to us.”

Shoshana Zuboff, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

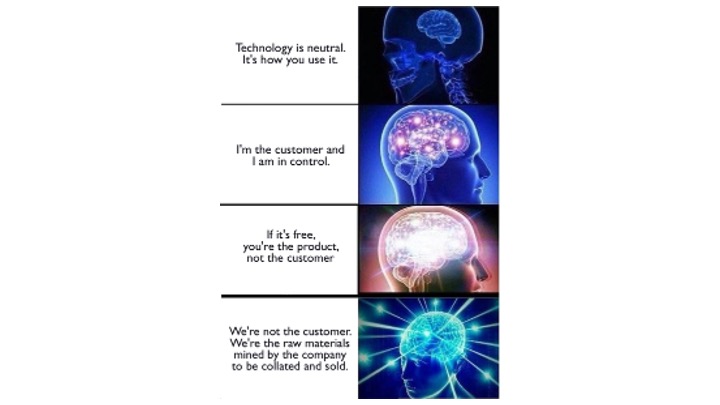

Here. I have made a meme for you… the medium is the message.

It is not just that tech is not neutral. It is not just “if you are not paying for it, you are the product.” We are being mined, and our thoughts and actions sold to companies who want to exploit us.

Data is being continuously collected from our phones, cars, homes, shops, smart watches, airports, loyalty cards, Amazon searches and purchases, our Netflix stream, our search history — where we tell Google our inner thoughts — and our status updates — what we project to the world.

And not just to sell us the stuff the algorithms know we want, but also to start changing what we see and interact with, so tech companies can change how we think about the world and whatever cause they like, in what she calls long-term strategies of manipulation intended to mould us.

“Personal information is increasingly used to enforce standards of behavior. Information processing is developing, therefore, into an essential element of long-term strategies of manipulation intended to mold and adjust individual conduct.”

Shoshana Zuboff, Surveillance Capitalism

Our brains have become the software, programmed by others so our hardware — our bodies — act accordingly. McLuhan also said “the medium is the massage” — our communication forms form us. But this is next level, especially when companies outsource this massaging of our brains to machine learning: to algorithms designed to maximise their efficiency.

You might be worried about technology because you have noticed its impact on your well-being — whether that is the way you are addicted to screens, to doom-scrolling, to games, to porn, to whatever is giving you a dopamine hit. Lots of the tech we are addicted to is designed to grab and keep your attention using the same chemical reward cycle stimulating techniques as poker machines — designed to addictively link your brain chemistry and the machine.

You might have recognised that technology promises connection, but is objectively leaving users lonelier than ever.

But are you worried about how the algorithms that drive lots of machine-learning processes are racist, or amplify the bias we find in human behaviour? Not just chat bots that learn from Twitter, but the algorithms programmed by experts? You should be. Google sacked its internal expert on this stuff, and she has gone on to start an independent think tank on tackling racism in artificial intelligence. That said, Google just sacked another engineer who believed the bot he had been working on had become human…

But that is not all. Machines can now — with human help — make stuff that leaves us constantly having to question what is true and what is real. Whether that is deepfakes, where content can be generated using audio clips and videos to make anybody do or say just about anything, or randomly generated human faces, like this person — who does not exist — just like the lady in our series graphic.

These images can be used in just about any way. You could use AI to make a person who does not exist do or say things in a video.

And, of course, there is fake news. Not just the way people within our democracy might flood social media with disinformation, but how foreign troll farms are dedicated to flooding social media with memes geared to fuel destabilising polarisation.

Technology is not neutral. It can be disenchanting — like the clock. It can deny our limits — like the car, or the hologram, or the screen. It can make us less God-dependent, and more dependent on ourselves. Not just modern medicine — which is great — but the idea we can use tech to become immortal in the clouds — which is not so great.

Idolatrous technology distorts the way we live in the world, and ultimately it is part of what is disintegrating us — our societies, and our own lives — as we are pulled beyond our limits and in thousands of directions all at once. Sometimes the pull is from algorithmic sources we cannot see or understand, and sometimes it is just our own chemical dependency fuelled by our addiction. Often it is both at once.

And this comes back to Jacques Ellul’s diagnosis of modern society as a technological society built on the myth that technology and technique — the machine — always produces progress. He published this the same year as Lewis’s lecture. This is the idea that living right is about picking the right technology and techniques to maximise efficient outcomes. Think about the way, at about this time, machines were producing maximally effective fast food. He believed this was fragmenting us then, in 1954:

“Technique has penetrated the deepest recesses of the human being. The machine tends not only to create a new human environment, but also to modify man’s very essence.”

Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society

Just imagine what happens when we bring this story about technology and technique into our lives as disciples of Jesus, and into our life together as the church.

We do not have to imagine that — many of us have lived it, and we are recovering from the feeling of being part of a machine; fast-food church. Some of us have followed the podcast The Rise and Fall of Mars Hill, basically the story of a church that was a technological society, fully embracing technology and technique in a digital world, to pursue limitless numerical growth, whatever the cost.

The fast-food church idea that a church should grow to 10,000 by building efficient systems, or should go global by streaming one man’s — it is always a man — one man’s preaching into auditoriums and lounge rooms around the world, where no questions get asked about that because the technology allows it… That is this technological age, and this is when tech turns idolatrous.

And so — what is the way forward? How do we be truly human — image bearers who create as people made to create? Who make tools and technology that can either connect us to God and his story, or become gods that disenchant the world? How do we resist technology that pushes us to deny our limits, distort the way we live in the world, create dependencies in our brains and bodies, and ultimately disintegrate us? All while digital Babylon — the world of surveillance capitalism — wants to use the magic of technology, and its promises, to disciple us, and exploit us while they build their towers?

Are we facing a looming disaster?

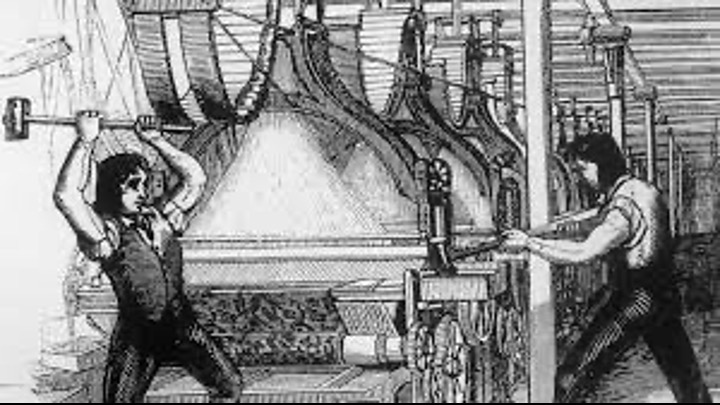

In the nineteenth century there was a collective of English textile workers who recognised the way the mechanical loom was reshaping life not just for them — taking jobs — but the way mechanisation was going to change life as they knew it. They got together and called themselves the Luddites. You might have heard of them. They tried to destroy mechanical looms wherever they got their hands on them.

I know some of you are thinking “OK boomer” when I talk about technology like this. But maybe you should be thinking “OK loomer.” Only, it is not that simple.

There are people who believe we should go back to monastic life to escape the power of technology. But that misses the fact that we are made to make — to make the world more like Eden.

I do wonder if we should be a bit more Amish. They are not anti-tech, just really slow to embrace new technology. They embrace limits, and carefully consider the changes technology will bring to their lives as individuals, and as a community, changing slowly and carefully, to resist the patterns of the outside world.

It is too late for us, though, right?

We have embraced so much of this technology and become addicts who are chemically wired into the machine.

And maybe there are some technologies we have embraced that are dehumanising us, that we need to walk away from like recovering addicts. There are new technologies we can resist, when we see forces of surveillance capitalism at play, and the risks involved in a smart toilet… or a hyper-connected world.

And yet, perhaps we Christians could also be at the cutting edge of technology if we thought about it deliberately, and built things according to our understanding of the world, and of being human. What if we made technology, or embraced techniques that reminded us of our limits, and of our place in an enchanted universe, pushing back against universal black glass and smart toilets?

And look: this would all feel abstract if a bunch of you were not super-genius tech and maths geeks at the start of your careers. Or in the middle. Or the parents and grandparents of people who might be. Or if some of you were not working out how to hack and redesign medical machinery to solve problems in the developing world.

This is the stuff of everyday life. Technology is inevitable. It is part of being human, because we are tektons made in the image of a tekton. The catch is we have the furious opposites thing going on, where tech can either make us more human, for the glory of God, or dehumanise us through idolatry. And we have to ask about the story technology teaches us — both medium and message — and how we connect ourselves to God and his creative work in creation and redemption.

Following Jesus the tekton — the creative Word who became flesh; coming as a user and maker of tools and technologies — who worked with his hands making things for thirty years, before taking part in the rebuilding project of bringing his heavenly Father’s kingdom to earth. Restoring us as images.

There is a cool thing in that bit from Ephesians we read. Paul says that we are God’s workmanship, his handiwork (Ephesians 2:10). This is a word that only turns up in one other place in the New Testament — in Romans 1:20, which talks about how we were meant to know God from what has been made — his handiwork. We — the church — we are God’s creative act, created in Jesus, to show the world what God is like as we do the good work — including the technology-making and the techniques we adopt — that reveal his nature to the world. We are saved by the work of Jesus the tekton, not our work, so God’s making is on display in our making.

We are re-created by a creator to do good, and that means creating technology and techniques — ways of being — but also living differently to the people in this world who are ruled by the prince of the air. That is the devil (Ephesians 2:1–2). Which means resisting the idolatrous mythology that surrounds technology, and the way some of that idolatry is aimed at making us like God. Just like the bricks in Babel, pushing us beyond our limits — time, space, even death — that will ultimately destroy us. Figuring out where technology is pulling us towards idolatrous self-sufficiency, and away from God’s work, will require big-brained discernment: knowing what technology can do, spotting myths and destructive patterns in our personal lives, and in our life together, and in the world. We can become like automatons united in a machine, or parts of a living body united by an animating Spirit. We have to work out together when technology is good to embrace, good to resist, and what is good to create. That will take wisdom.

What Paul says a bit later in Ephesians brings us full circle — back to the candles — the idea that God is light and life and that we should live as children of the light (Ephesians 5:8). And he does not mean backlit glass screens, but those who see the world as the workmanship of the God who said “Let there be light.” Paul says be wise and careful in how we live (Ephesians 5:15), which certainly includes thinking about technology. He says the days are evil; there is a prince of the air out there, making the most of every opportunity — or literally “redeeming the time” (Ephesians 5:15–17). Life on the clock tells one story about time. But we are called to occupy time differently; seeing our days as days lived before God, doing his work.

And maybe that means we need more candles — technology that pushes us back against the particular technological idolatry of our time. Tish Harrison Warren talks about how we are trained — discipled even — by our use of technology to spend more time on screens, a world away, focused on the trending and distant, so we miss the small and close features of embodied life:

“We are creatures made to encounter beauty and goodness in the material world. But digitisation is changing our relationship with materiality — both the world of nature and of human relationships… We are trained through technology (and technology corporations) to spend more time on screens and less time noticing and interacting with this touchable, smellable, feelable world.”

Tish Harrison Warren

She believes just as people have resisted fast food by turning to slow food, patterns of eating that are less about technology and technique, and more local and connected, we should embrace slower life in order to reconnect with our bodies, our limits, our community, and our God.

“Just as people have worked to revive slow, unprocessed and traditional food, we need to fight for the tangible world, for enduring ways of interacting with others.”

Tish Harrison Warren

Which raises the question: if some versions of church have been the equivalent of fast food — triumphs of pragmatism, technology, and technique — what does it look like to embrace slow church; church life that teaches us our limits?

We are certainly a bit minimalist, deliberately, as a church when it comes to technology. And we have tried to bring in some ancient stuff to resist modern patterns. Paul describes some mediums — techniques — that will keep us connected to God, and to each other. They are ancient techniques we still use in our life together: as we sing God’s truth to each other, always giving thanks to God the Father for everything, in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ (Ephesians 5:18–20).