This is an adaptation of the second talk from a 2022 sermon series — you can listen to it as a podcast here, or watch it on video. It’s not unhelpful to think of this series as a ‘book’ preached chapter by chapter. And, a note — there are lots of pull quotes from various sources in these posts that were presented as slides in the sermons, but not read out in the recordings.

I want us to use our imaginations for a bit — with some help from some art.

Imagine you are a farmer in a French village. It is about 1400 AD.

You work in fields owned by the local lord, whose job was providing order. He is part of a chain of rulers — appointed by the king, who was crowned in a ceremony in church to show he is a reflection of God’s rule over the world.

When you finished work, you would head to the public square, where the skyline was dominated by the steeple of the church — a building whose art and furniture and layout, at the heart of the village, were part of teaching villagers to be human.

If you got sick, or the weather caused your crops to fail, you would wonder how the spiritual world was at play. This painting shows people being struck down by plague.

The Black Death — a pandemic — had been sweeping through the world for fifty years, killing two thirds of the population in your village. Nobody knew what to do. If you went to the big city you found the borders closed, like in this painting, and you would have to die at home, or find a monastery to care for you.

Reality was a playground for angels and demons. The heavens and earth overlapped and were involved in everyday events.

Your version of Christianity was fused with folk religion. Not only were religious relics with miraculous powers touring from town to town, but if you wanted a bumper harvest you might pocket a piece of Communion bread and plant it with your crops.

Time was marked by holy days — feasts provided by the lord and the priest — moments of embodied celebration connected to stories from the Bible, and the lives of the saints. These also worked to reinforce an enchanted view of reality where heavens and earth overlapped.

Our guide to the secular age, Charles Taylor, says the human in this world had a porous self — open and vulnerable to forces, but also living in this order. While he calls the modern self ‘buffered’ — cut off from that reality.

“A crucial condition for this was a new sense of the self and its place in the cosmos: not open and porous and vulnerable to a world of spirits and powers, but what I want to call ‘buffered’.”

Charles Taylor

He calls the backdrop — the infrastructure, social structures, communal rhythms, and stories, the stuff that shapes our imagination and beliefs — a “social imaginary.”

“I want to speak of ‘social imaginary’ here… because I’m talking about the way ordinary people ‘imagine’ their social surroundings… it is carried in images, stories, legends, etc… that it is shared by large groups of people, if not the whole society.”

Charles Taylor

Things were not great back then. Obviously. Deadly pandemics without medicine. A social order you were born into where your life was determined. Living at the whim of the weather without farming technology providing food security. Corrupt human authorities claiming to act for God.

People needed a revolution — the Renaissance — an explosion of art and culture and new ideas, a new social imaginary that included the development of humanism, and the philosophical concept of the individual.

We tend to assume this framework — that we are a self; in control of our own identity; that we belong to ourselves — but individualism is a development in the West.

The French politician Lord Montaigne wrote about the idea of self-ownership — he only wanted to lend himself to others, not belong to them, because we should only give ourselves to ourselves.

“As much as I can I employ my self wholly to my self… My opinion is, that one should lend himself to others, and not give himself but to himself.”

Lord Montaigne, 1588

An idea the English philosopher John Locke picked up one hundred years later when he said every human has a property in their person that no one else has a right to, and it is the same with the work of our hands. This idea produced liberalism, and democracy.

“Every individual man has a property in his own person; this is something that nobody else has any right to. The labour of his body and the work of his hands, we may say, are strictly his.”

John Locke, 1689

Where we are our own.

There was another changing of the social imaginary in the mix here; the church was going through its own revolution — a Reformation, because it had become corrupt. The Reformation and Renaissance go hand in hand.

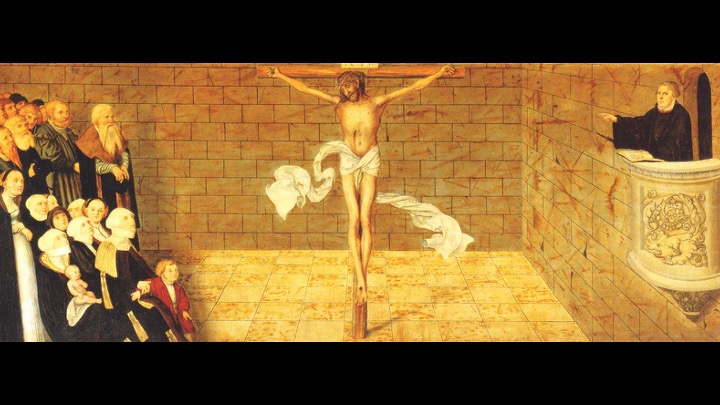

Tara Isabella Burton wrote Strange Rites — a book about our modern religious sensibilities that emerge out of the modern self. She charts how Protestantism, in particular, drove the move from institutional to individual, starting with Martin Luther’s emphasis on a more individualistic path to God.

“Religion itself heralded this transition from the institutional to the individual… Protestantism — particularly Martin Luther’s vision of religion — pioneered a different and far more individualistic path.”

Tara Isabella Burton, Strange Rites

His emphasis was on personal faith and the individual, on reading the Bible freed from corrupt religious authorities.

“Luther saw the experience of Christian faith as primarily a personal one; the relationship between the individual and the Bible was one that no outside body or cleric had the authority to encroach upon.”

Tara Isabella Burton, Strange Rites

Luther was a priest who was also a humanist lawyer. When he looked at the corruption of institutional power, and at the Bible, he re-articulated the way the Gospel did not say you are saved by your relationship to the institution.

This painting of him preaching has him holding the word and speaking from it to put the atoning death of Jesus in front of people, and the salvation of the individual through faith in Jesus.

Which was good. Except maybe that it led to the collapse of some other truths that had been part of the social imaginary. Luther, and Reformers after him, were so keen to go back to the text that they started a demolition of the church’s view of the sacraments — dropping the number from seven to two — and of folk religion — like magic relics, or planting Communion bread.

They also demolished festivals — things that had structured people’s experience of time and space.

There was another factor here — technology. While all this was being removed from the rhythms of life, the printing press meant more people had books. It changed who got to tell the stories. And unlike the institution, Protestants were so keen for people to be able to read the Bible for themselves that they started schools for everyone.

This education program shifted how we understand being human. We became much more focused on filling the brain with words, than on how we used our bodies. The self was a product of the mind, where we could be absolutely sure we belonged to ourselves. This inner self became the starting point for our relationship with God.

There are pretty clear lines we can draw from this changing of the social imaginary to disenchantment.

There is lots of great stuff about Protestantism that we probably love. But in these revolutions there is a reaction against one heresy — the “furious truth” that we are not our own — with the “furious truth” that we are individuals.

It is true that you — you as an individual — are made in the image of God; you have personhood and dignity as a gift from God inherent to your being (Genesis 1:27). It is true that we are equal before God, and that the Gospel has implications for you as an individual built on your relationship with the God who gives everyone life and breath, and in whom we live, and breathe, and have our being (Acts 17:25, 28) — the triune God who is a communion of love (1 John 4:8, 16).

And it is also true that we belong in a communion with others that reflects God’s nature. Part of imaging God, being human, is in the plural “them.” We are human in and through relationships. Part of our humanity is actually a product of the relationships that produce us, that give us love and attachment as we belong to our communities. At their best these communities are part of our social imaginary that teaches us about God and the universe we live in, because we are representing God.

And heretical movements, both in the church and in the world, have picked either of these truths — that we exist as humans in community, and that we exist as humans as individuals — and placed them at odds with each other. That is part of what pulls us apart.

One way to observe these heresies at play is in our own plague — the pandemic and our response to it. Think about what you might call the right and the left. In a liberal democracy both these poles are still going to be built on individualism to some extent, but the right tends to emphasise the individual self; individual responsibility, while the left tends to think about systems or societies of individuals — social responsibility.

We have had to face a disease that has brought death, in large numbers, around the world — and for most of our neighbours that has happened in a new social imaginary without God to give us comfort, and with the idea not that this could be God’s judgment, but that we humans have to fix it. We turn to technology like masks and vaccines to save us.

And the mask has become a revealer — which is ironic. It is meant to cover things. But it has revealed our fractured social imaginary. The same with lockdowns, vaccines, and vaccine mandates.

Dr Clare Southerton, an academic from Sydney, has studied the way masks have done this in Australia, and the West. She says:

“Masks have really become politicised around the issue of personal freedom – about whether governments and health officials have the right to require individuals to wear masks… issues of personal freedom versus collective good are being negotiated.”

It is a furious opposites moment where both are true. But where political polarisation is happening because we are still heretics at heart — and these are both Christian truths unmoored from Christianity.

The thing about movements built around polarised positions like this — around our intuitions and our heresies — is that we turn to new social imaginaries, new social media story-tellers, and new festivals of belonging to have our identities recognised and reinforced.

Whether that is an anti-vax “freedom” movement, a Black Lives Matter movement, a Pride march, a football game… These are rhythms and rituals that help us with a sense of self as we bring our inner self to the world, and engage our bodies, and even dress them, so that we are recognised in a way that helps us feel human. They fill a void of something we have lost from when we lived with God as our witness in this human-centred universe where we need other people to witness us. Charles Taylor talks about this as being part of a culture of expressive individualism, or a culture of authenticity, where basically we boil things down to “finding our way” while “doing our thing.”

“There arises in Western societies a generalised culture of ‘authenticity’, or expressive individualism, in which people are encouraged to find their own way, discover their own fulfilment, ‘do their own thing.’”

Charles Taylor

While Tara Burton says we have replaced institutional religion with intuitional religions:

“Today’s new cults of and for the Remixed are what I will call ‘intuitional religions.’”

Tara Isabella Burton

We have moved from doctrine and dogma and hierarchies and any story that we are given, and replaced it with our own authority — self-authoring ourselves from our gut instinct as we navigate our experiences.

“By this, I mean that their sense of meaning is based in narratives that simultaneously reject clear-cut creedal metaphysical doctrines and institutional hierarchies and place the locus of authority on people’s experiential emotions, what you might call gut instinct.”

Tara Isabella Burton

Now we have to figure out who we are as people who have buffered ourselves; cut ourselves off from anything outside our mind, and defined ourselves from within. In the modern world this is where we talk about identity; the idea that we have to discover who we are on the inside, and express and be recognised as who we are on the outside in a way that matches.

“For the modern, buffered self, the possibility exists of taking a distance from, disengaging from everything outside the mind. My ultimate purposes are those which arise within me…”

Charles Taylor

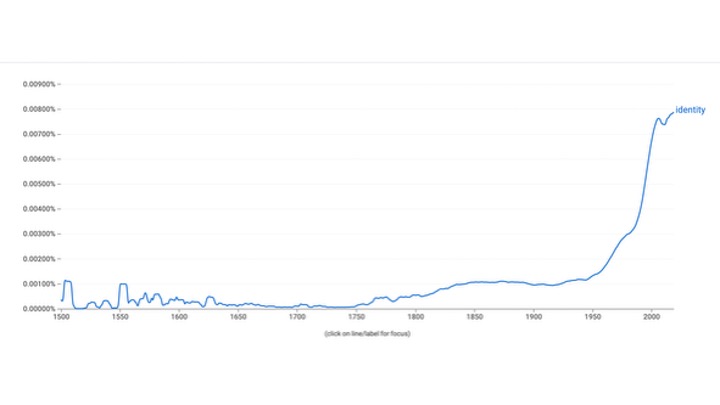

You might have heard people say that we should “find our identity in Christ.” But I believe this can be a dangerous way to assume this modern model of the person. This idea of identity — used the way we use it — is a new thing in the English language; newer than the individual and the self.

Google has this tool called the N-Gram — it shows the frequency that words appear, as a percentage, in books published since 1500. Look at this. There is a real uptick in the 1950s that can be explained by two academic disciplines — psychology and sociology — both using the word to mean two slightly different things to answer the question “who am I” for a world rapidly breaking up with God.

In psychology, identity is about your inner self and finding ways to live consistently. In sociology, your identity is something performed and recognised by other humans, in a group.

So now we live in a world where everyone has to work out their identity question from within — belonging to themselves — and have it recognised by others. And so, in these words from Alan Noble’s great book You Are Not Your Own:

“Everyone is on their own private journey of self-discovery and self-expression, so that at times, modern life feels like billions of people in the same room shouting their own name so that everyone else knows they exist and who they are — which is a fairly accurate description of social media.”

Alan Noble, You Are Not Your Own

We have to do all this in a world where complexity and speed mean we still cannot see the invisible forces that make things happen. But we are pretty sure it is not demons.

“Complex systems are often characterised by an absence of visible causal links between their elements, which makes them impossible to predict.”

Klaus Schwab, Thierry Malleret, The Great Narrative: For a Better Future, World Economic Forum

And when we face big problems it is not on God to fix things; it is on us — and often the “us” there is individual.

Think about how climate change has become an issue you have to solve by your decisions and actions — like turning off the lights, or cutting plastic out of the picture. Now this is good creation care; good stewardship. But your small changes — like not using plastic straws, or bread tags — will not make a difference if there are not also big systemic changes; changing legislation or companies changing how they work.

Even the Great Narrative says tackling overwhelming stuff starts with you. You have to get it right.

“Tackling an issue that seems overwhelming begins with practicality – with every one of us acting and focusing on the things within our remit, like being empathetic towards our fellow human beings, reaching out to those in need, making the right decisions on how we engage with others, eat, shop, travel, vote, and more.”

You have to navigate these invisible forces in a complex world and make all the right decisions.

And you cannot.

There are two risks with all this for Christians.

The first is that we treat our Christianity as though we are modern people creating an identity — seeing coming to church as just like a rally, or a preference we perform to be recognised; just one choice we make while being true to ourselves and belonging to ourselves.

Maybe you can picture people you know who tack Christianity on as something like a brand; who pose for photos with Bibles outside a church, while nothing else about their life changes.

Or maybe it is you. Maybe church is one of many identities where you perform, then jump to something else… not as an integrated person, but as a dis-integrating person; wearing different masks, performing different identities in different communities as you remix religious ideas following your intuitions.

This is not what church is; and it is not how we are created to live.

Christianity is not a preference to be performed; an exercise in self-expression. It is not an identity we have to shout at people on the internet, even if we might use the internet to point to Jesus.

There is a risk when we bring in the category of identity that we focus on being human as individual selves, and that Christianity becomes a psychological or sociological thing, where we use God as part of an answer to our question “Who am I?”, rather than changing the question to “Whose am I?” — realising that God gives us our humanity, and we become truly human not by our choice, but by receiving his gift of life and communion with him.

The second risk is that we can slip into thinking as individuals when it comes to our own complex problems. We tend towards putting responsibility for godliness on individuals — saying “fix yourself through discipline” rather than cultivating communities where individuals are encouraged and discipled in godly ways.

Think about how we talk about addictive, sinful behaviours as though they are simply a choice, when often they are products of sinful systems that benefit from addicting us to things; and from bodies that carry trauma memories, and brains addicted to dopamine hits, in a world where we have been set up to believe individual fulfilment is the best thing, and we get that by consuming more of what we want.

Our sinful individual actions are sin that we are responsible for; absolutely, that is true. It is also true they are products of social imaginaries created to reinforce these same sinful behaviours, so that the answer is not just personal change by an individual self.

We can end up with a faith that puts all the responsibility for godliness on your shoulders. And your brain. “You have an addiction? Fix it by thinking right. Read more Bible. Know more stuff about God. Choose right. Take some ownership. Belong to yourself.”

We will ask no questions about how our culture — whether in the church, or in the world — is breaking you and pushing you towards coping strategies… about what is going on in your brain… we will just tell you to self-improve… And “self-author;” “self-justify;” “save yourself” by getting your works right. This move is an anti-Gospel and it leaves us crushed by our inability to actually do it. And then the world tells us the answer to being crushed is found in the world — it is in technology, and techniques — medication, mindfulness, our coping strategies — porn, alcohol, coffee, work. And so we go back to our addictive behaviour and the cycle continues. Avoiding these risks is hard enough without living in a social imaginary that bombards us with an almost limitless number of stories about reality that reinforce our disintegration. A world built on the heresy that you are your own.

We spend all this time asking “Who am I?” and “How can I self-improve?” — but we actually need to spend more time asking “Who is God?” and “What does that mean for us?”

This is where our readings are really helpful — and where we find a phrase that became the first thing in the Heidelberg Catechism, a teaching tool from early in the Reformation:

You are not your own.

Q. What is your only comfort in life and in death?

A. That I am not my own, but belong — body and soul, in life and in death — to my faithful Savior, Jesus Christ.

Heidelberg Catechism, 1563

The right thing to do; both in creation — where, because we are made in God’s image, and in God’s story of salvation, is not to “own ourselves” or “lend ourselves out,” but give to God what is God’s. We are not our own because we have been bought, redeemed, at a price. The price paid by Jesus, the true human — who showed us what it looks like to give yourself fully to God as he did. He did not just lend a bit of himself but gave his life, his body, to bring us into communion with God.

Paul uses this truth against first-century expressive individualism. People were saying “It is my body, and I have rights to pursue my own way” — around food, and worship, and sex, but Paul offers an alternative to the crushing pressure of belonging to ourselves, and to being pulled in every direction by our desires, and those telling us they will fulfil them without God in the mix. He says our bodies are made for communion with the Lord (1 Corinthians 6:12–13). So that we find our life in God as God lives in you, and transforms you with his Spirit dwelling in you — so that you become his temple. Because you are not your own. You were bought at a price; you belong to God (1 Corinthians 6:19–20).

And there would be a tendency for us to individualise this, right — to think this is a transformative truth about me, the individual… that is who I am. I am a temple. My body. I should diet, go to the gym, and not get tattoos.

But there is a catch. Because the “you” here is not just you. We heretics read it this way…

It is youse — like two thirds of the time the word “you” is used in the New Testament; these are plural in the Greek.

“Do you not know that your bodies are temples of the Holy Spirit, who is in youse, whom youse have received from God? Youse are not youse’s own; youse were bought at a price. Therefore honour God with youse’s bodies.”

1 Corinthians 6:19–20, New Plural Version (NPV)

This is a picture of a new reality for us as individuals-in-community — and our bodies, that are temples of the Holy Spirit, and are bought at a price. United to him, and each other, by the Spirit, to play this visible role of the presence of God in the world; to teach each other about the reality of the heavens and the earth because God’s Spirit dwells in youse.

Now, what the church building and festivals were in our medieval village, the temple was in Israel. It was the centre of the social imaginary. The rituals and rhythms of Israel’s community life were centred on this place that taught them about the heavens and earth, their story, and God’s character: his holiness, his love, his judgment and forgiveness; his desire to be present in order to live in relationship and restore people to life with him.

We have a new social imaginary to shape our belief — it is our bodies. Together.

Not just my body as an individual, but the way we use our bodies in community — in communion — in ways that express our story and our hope.

Our bodies are another thing we Protestants disenchanted in our rush to the mind. But how we use them is going to teach us about God, and belonging to him as we belong to each other.

Paul is going to take this idea about the body through to how married Christians act in private, and in public, when husband and wife belong to one another (1 Corinthians 7:4), and then how the church community, a new social imaginary, operates as one body, with one Spirit (1 Corinthians 12:12–14).

A communion — of many individual parts — all working together in a dynamic, God-created way. He put us together. That teaches us about the oneness we have been bought into and brought into by the body of Jesus, as we live as the body of Jesus (1 Corinthians 12:24–25, 27), taking up the most excellent way of love (1 Corinthians 12:31, 13:4). The way of God. This is what it means to be truly human because it is what it means to be the image — the body — of Jesus in the world as people united in him.

So how do we get back to seeing the world right? To understanding ourselves this way, in an enchanted world where God rules? Without bringing back corrupt kings or priests — or being enslaved by those who would dehumanise us by trying to make us, our bodies, belong to them. How do we see the world in a way that does put the body of Christ in front of our eyes as we open God’s word, but also as we live as the body of Christ, shaped by the Gospel together?

We need rhythms for our bodies; a story to shape our view of the world and life in it, not for our individual inner self, but for our communal life as we operate as God’s temple — his image bearers — for each other and the world; as we represent the God who is love, who gives himself to us — in the Son and the Spirit — to justify and redeem us and make us truly human, truly his. Not needing to ask “Who am I?” because we know the real question is “Whose am I?”

We need a new social imaginary.

We, together, need to cultivate new art and architecture in our lives that teaches us who we are — not just how to think, but how to be human — in a community embodying this reality. And that is what the church, the body of Christ, is.

We have abandoned the church calendar — the holy days — so we march to the calendar set for us by Westfield, who co-opt Christian days — Easter and Christmas — and even saint days, like Valentine’s — to sell more stuff to us, keep us consuming. Which is one of the reasons, as a church, we have started thinking about the church calendar more — especially around Advent.

We need to tell a better story — but not just tell it — move it from a story we hear to a story we live. One we participate in with our bodies. Which is one of the reasons we Presbyterians were so quick to jump on board with weekly Communion. We could see that as an empty ritual, and it can become one, but the key is to make it meaningfully connected to truths about God. Doing this regularly is a feature, not a bug, that makes it part of our rhythms — our framework for belief.

We need to cultivate a sense that we belong to a community way beyond ourselves — a communion with other people that includes those of us in the room, but also connects us even to the villagers we imagined back at the beginning. That is one of the reasons to say the Creed; not only do we say big truths together, but we are remembering connection to others who share our beliefs — and most importantly to God.

We stand and sing together — not singing as soloists, but a choir — whose voices join together in worshipping God; praising him for his goodness in creation and redemption; recognising that we belong to him.

We eat together and celebrate that we are now a community, a family, a body.

And we need to cultivate patterns and rhythms of serving each other. None of this is only about Sunday; a social imaginary operates 24/7, and there is a powerful one out there teaching you that you belong to yourselves. We actually have a calling from God to be building an embassy; being a temple — a picture of an alternative way of life to a world full of people being torn apart by the belief they belong to themselves and that is it.

We need to spend time in communion with God — meditating on his word, not just as ideas, but seeing the life it calls us to. And in the sort of silent, contemplative prayer we practiced last week that teaches us about our limits and about God’s place in the cosmos, and that we do live and find ourselves before God, rather than before the audience of our peers.

None of these are silver bullets. They are also not just individual practices, but they might shape our imaginations and help us to practice godliness in our own lives. They are practices designed to pull us out of ourselves and connect us to the life of God that we have been connected to by Jesus; to teach us that we are not our own, but have been created and redeemed by a God who loves us and justifies us, and who does the work to save us — even from ourselves.